|

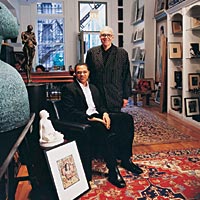

Photo: Lisa Predko |

| Silverberg (left) and business partner Bill Adams |

The big round glasses are right. So, too, the fashionably dark suit. Yep, Joe Silverberg looks like an art dealer. But he sure doesn’t come across like one. He’s too genial. And his Maison Rouge Galérie, in the old Tree Studios building at 619 North State Street, reads more like a funky retail store than a high-end art outlet. For years, Silverberg, 58, and his brother Gene were a CEO’s best friend-many of them dressed for success in threads from the siblings’ Bigsby & Kruthers clothing stores. So did Michael Jordan, who granted the brothers the use of his name for a River North eatery. That restaurant went under in 1999 (the following year, Jordan won a legal battle regaining the exclusive right to put his name on a Chicago restaurant). Credit problems and the dressing down of the American male doomed the retail chain, which closed in 2000, and Joe has been keeping a fairly low profile since then. Throwing his hat into the ring as dealer might seem a quixotic move to those who remember him as a rag merchant, but Silverberg has long had an eye for art and often used to end his day with a visit to the studio of Ed Paschke or Tony Fitzpatrick. “They were doing what they wanted to do, where they wanted to do it, and when they wanted to do it,” Silverberg says. “They had an independence that most people in business don’t. I was always attracted to that.”

Born in Berlin, Silverberg grew up here, first on the West Side, and, after several moves, in Rogers Park. “I went to six different grammar schools,” he says. At 11, he was hawking shoes on Maxwell Street; in 1970, at 23, he opened his first Bigsby & Kruthers store at Broadway and Briar. Brother Gene joined him in the venture three years later.

Maison Rouge, a project also backed by Silverberg’s wife, Sherry-whose personal collection forms much of the inventory-and partner Bill Adams, a trader at LaSalle Futures Group, offers works in various media from roughly 1900 to 1950, as well as some contemporary pieces. Black subject matter by artists black and white is big here. Photographs, too: Carl Van Vechten’s portraits of Harlem Renaissance luminaries, stylized nudes by the Czech photographer Frantisek Drtikol, Annie Leibovitz’s take on Miles Davis. There are expressionist drawings by Rudolph Weisenborn (1881-1974), whose WPA mural Contemporary Chicago appears in the Nettelhorst School on North Broadway, and the neo-surrealism of the contemporary Italian artist Pino Tersigni.

So, is moving a still life that much different from selling a suit? “I’m a merchant,” Silverberg says. “I’m here to sell. An article of clothing, someone comes in, you take good care of them, you make them look good-if the price is right, boom, you wrap it up and they’re gone. But with artwork, it’s a decision that is not necessarily made spur-of-the-moment.” Silverberg seems content to take a niche role in Chicago’s insular gallery world. “I don’t want to compare us to X, Y, or Z gallery,” he says. “The whole sale process here isn’t as stuffy. Because it doesn’t have to be.”