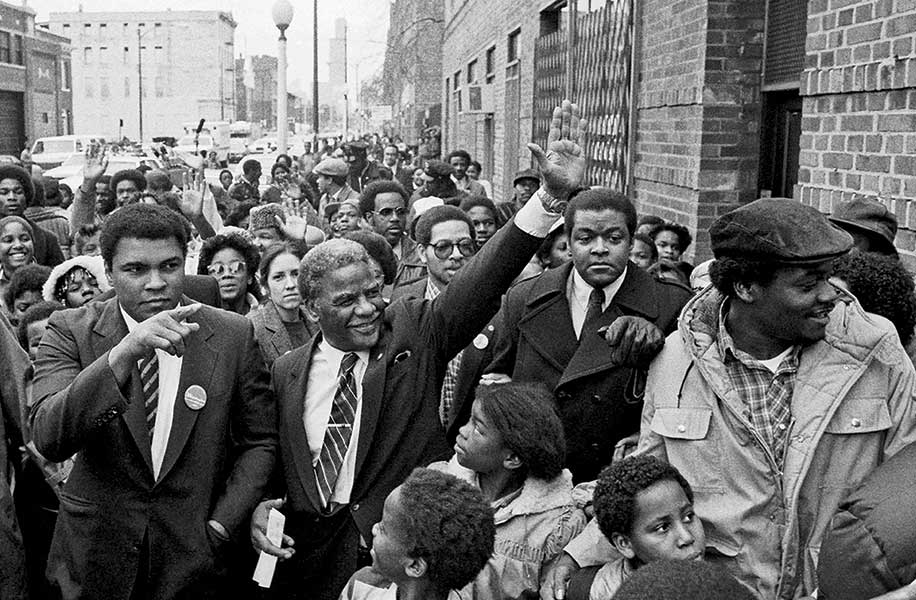

He wasn’t part of the insider crowd. He wasn’t somebody who the establishment immediately embraced. But he understood that, ultimately, power comes from people.”

With those words, spoken by Barack Obama in 2008 at the Congressional Black Caucus Foundation Annual Legislative Conference in Washington, D.C., the soon-to-be president could have been describing himself, but in fact he was talking about Harold Washington, whom Obama credited as an inspiration for his moving to Chicago in 1985, two years after Washington had taken office. Obama went on: “If you are working at a grassroots [level]—and people trust you are fighting for them—then there’s nothing you can’t accomplish.”

Revisiting those remarks on the 30th anniversary of Washington’s death, you can’t help wondering what the city’s first black mayor, who was just a few months into his second term, would have gone on to accomplish had his heart not stopped on November 25, 1987.

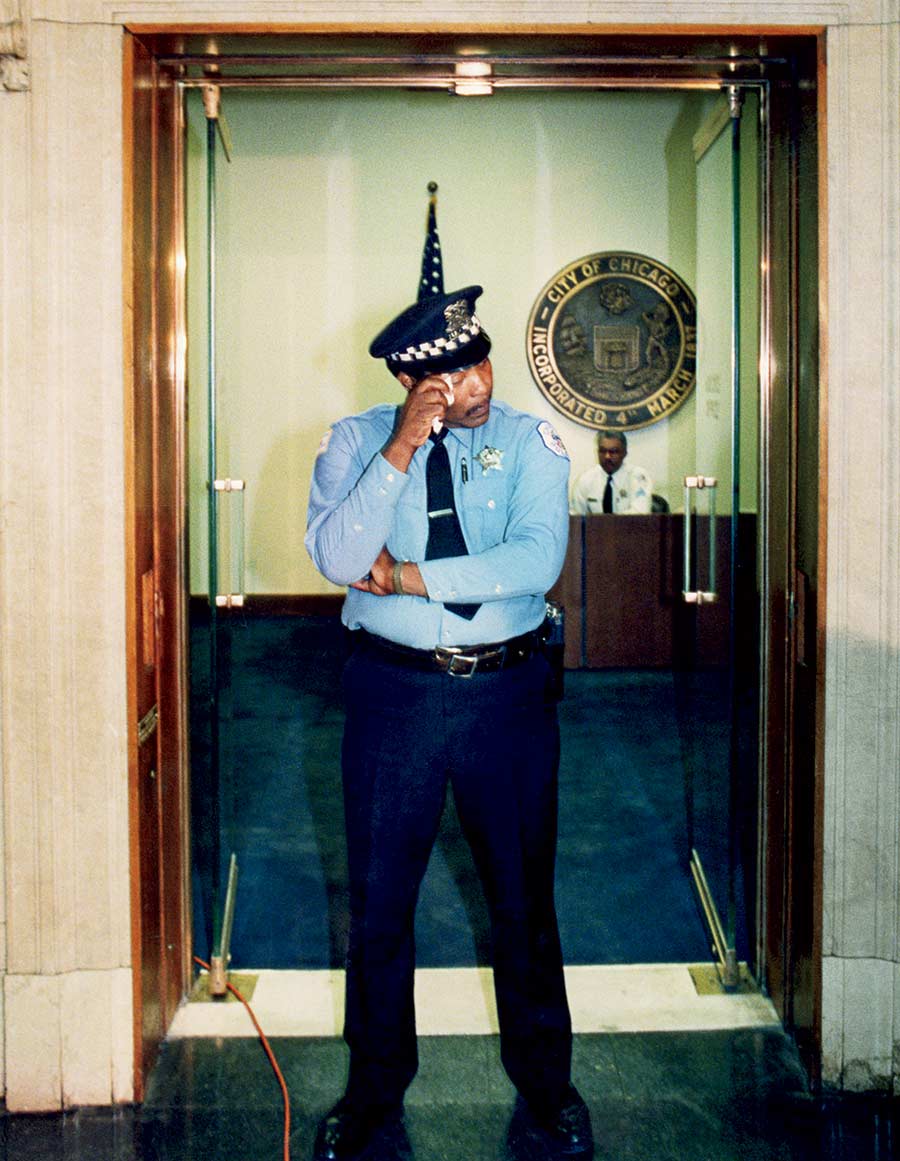

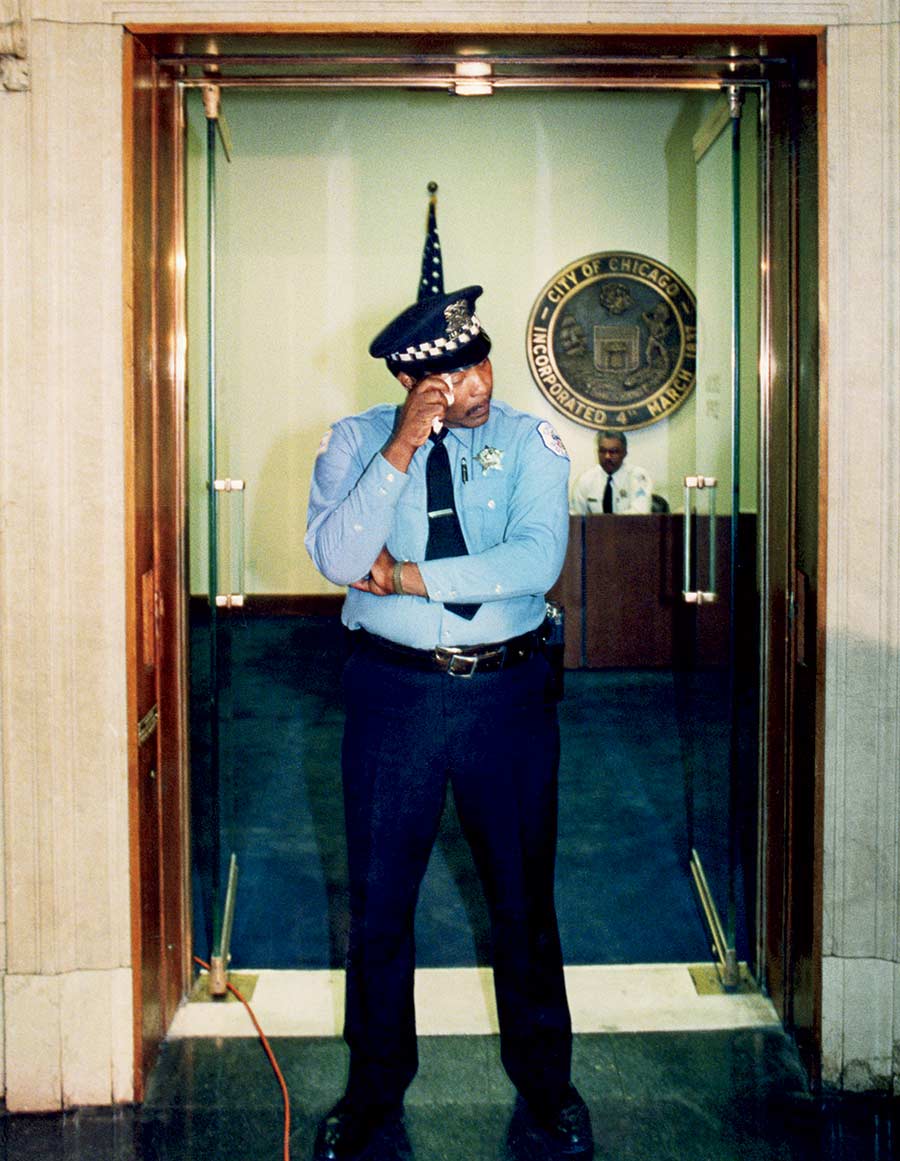

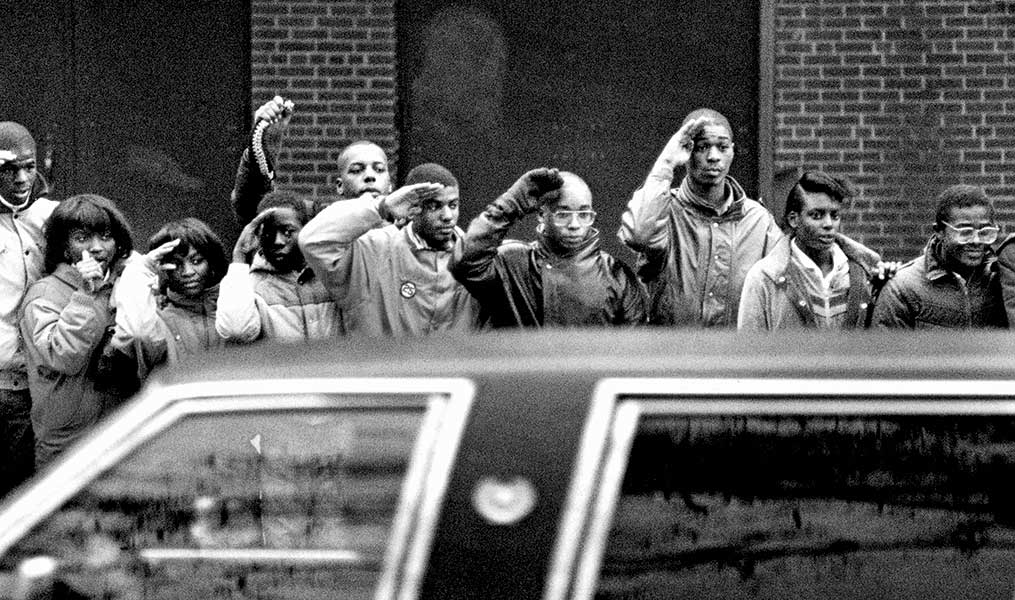

The Chicago Tribune’s coverage of that day depicted a city convulsed in grief: “Women sank, sobbing, onto plaza benches. A man sat and buried his head in his hands.” A memorable photo showed a police officer standing guard outside the mayor’s City Hall office—where Washington had collapsed just hours earlier—wiping tears from his face.

Washington, a former U.S. congressman, was 65 years old, overweight, an ex-smoker, and a notorious workaholic in a stressful job, yet his death hit Chicagoans—especially African Americans, 98 percent of whom had voted for Washington in the first election—like a gut punch. To many black residents, the loss of their charismatic, Bronzeville-born mayor threatened to extinguish four and a half years’ worth of progress in a city that had long been ruled by machine politics and marred by racial injustice.

During that period, having overcome fierce opposition from an obstructionist group of mostly white aldermen known as the Vrdolyak 29, Washington increased the number of minorities in local government, awarded a record number of contracts to minority-owned businesses, improved governmental transparency by granting the public access to official records, and formed an ethics commission to root out corruption. The mayor envisioned those and other moves as merely a start, quipping after his April reelection that he was going to be “mayor for life” and die at his desk. His prediction proved uncannily true, and all too soon.

Two days after Washington’s death, his body lay in state in the City Hall rotunda, drawing thousands of mourners. He was buried four days later at Oak Woods Cemetery, not far from his Hyde Park apartment. Early on December 2, over the vociferous objections of protesters who supported Washington’s widely acknowledged heir apparent, Timothy Evans, a majority of the City Council selected Eugene Sawyer, an African American alderman favored by the late mayor’s foes, to succeed Washington. In the eyes of many Chicagoans, the machine had regained power, and a momentous era was over.

But for a great number of those who knew and worked with the man, their impressions of Washington have faded little in three decades, and the things he fought for feel more urgent than ever. For a handful of people who lived through that November day in 1987, the memories are indelible.

Timothy Evans

4th Ward alderman

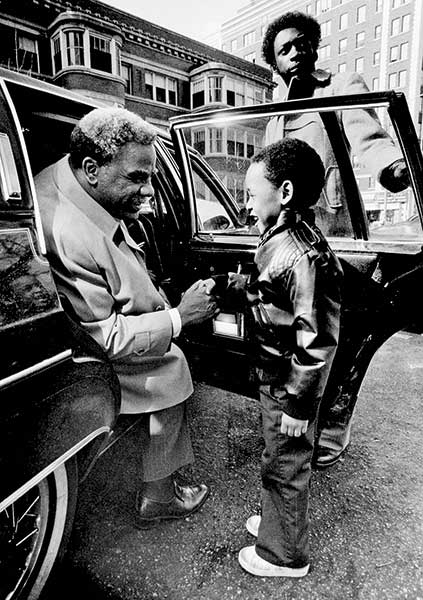

Harold was dedicating some housing in my ward that morning. He was in good spirits. He could be a very serious guy but also a jokester: When they gave us the shovels and the construction hats to put on our heads, I looked down and he was putting dirt from his shovel into mine. We were four or five blocks from my house, and so when we were getting ready to leave, I said I had to go home to pick up my briefcase. As he was getting into his limousine, he said, “Well, I’ll see you downtown.” And by the time I got home and got my briefcase and everything together, the phone was ringing. And I thought, Whoever it is, I can get it later. But it kept ringing, so I decided to answer it.

Even now, I miss the guy every day. I think about something that he said, one way or the other, almost every day of the year. I can remember once when we were in Beijing and we saw Chairman Mao’s mausoleum. He looked over and said, “I wonder how I’ll be remembered.” He wasn’t expecting an answer, and none of us gave him one, because we weren’t thinking about him leaving.

Alton Miller

Press secretary

The mayor once said, “I don’t know what it is, but the old ladies, they like me.” And wherever he went, that was true. You’d go out into neighborhoods where he’d be lucky to pick up five votes, and the babushkas would come out with their grandchildren to see the mayor and wave and pose for a photograph and get a hug. He was irrepressible in his personal relationships. At political rallies, whenever there was a huge audience of his own supporters, instead of coming in the back door, he would walk in the front door and through the crowd, all the way up to the podium. It would be like an imaginary spotlight was on him: You could see the sea of heads and the waves as he was making his way up. You’d have these ladies holding up their lottery tickets so he could touch them for mojo. It was like the king’s touch.

That morning, the mayor had some kind of congestion in the car coming back from the groundbreaking. We got back to City Hall and he asked one [member] of the security detail to bring him some cough drops. We were sitting in his office, and I was going through my Day-Timer and we were talking about what was happening that day, and I suddenly heard this thump. I looked up and he was slumped over on his desk. I thought he was trying to pick up a pen or something that he had dropped. Almost in the same motion, his chair flipped out from under him. I called for the detail—they were right next door—and told his secretary to call 911. The EMTs were up there in seconds, because a team was based on the first floor of City Hall. They started CPR and took his pulse. They had a pulse for a moment and then they lost it. They did telemetry [to allow remote monitoring of his vital signs] and had him hooked up via telephone to Northwestern Hospital [until the ambulance arrived].

Ernest Barefield

Chief of staff

I was in the office, and I got the message that he had been taken to the hospital. There was total quiet and disbelief. Many of us in the administration went to the hospital. We were there on the scene, prayerful and hopeful. Some said there was a chance that he might recover. We didn’t even know it was a heart attack at the time. But we had great hope that things would go on, that the journey wouldn’t end.

Patrick Keen

Project director for West Side Habitat for Humanity

I was always amazed by his mind, his abilities, his vision for the development of the parks and the boulevards and the neighborhoods that were connected to them. His vision for Chicago was so intriguing, and I bought into it immediately because I knew it was right for the city.

I remember being in my office that day, listening to NPR, and they announced that the mayor had had a heart attack. First I called City Hall and told them I wanted to set up a prayer vigil for Harold in Daley Plaza, which they accommodated. And I notified WBEZ that we were going to do that so they could announce it over the air. The crowd grew hour by hour as the word was going out. He had been to a breakfast, and there were rumors that he had been poisoned. [That speculation was later debunked.]

Jim Montgomery

Corporation counsel for the City of Chicago

Harold had a notion that he became mayor not to make a few people rich but to be a mayor for all the people. It was pretty clear to me that he loved what he was doing, and he would sometimes be really reluctant to take trips outside of the city because whenever he would leave, something would break loose and he’d feel bad that he wasn’t there. But here was a guy, too, who was his own worst enemy because he didn’t take care of himself. He was gaining weight. Some ladies would come by his place and bring soul food—that is not good for you. One time he was on his way to his doctor’s office and he was in the corridor of the hospital. He gets a damn call about something going on in City Hall and just went right back to City Hall, never having made that appointment.

David Orr

49th Ward alderman and acting mayor from November 25 to December 2, 1987

I got back to the aldermanic office and some of the [mayor’s] bodyguards were there. They told me what happened. They told me to change clothes and get downtown immediately, so I knew he was in very bad shape. The day before, I’d had the longest one-on-one conversation with Harold in the whole time he was mayor. He’d won again and had a stronger coalition. But there were still certain criticisms from the progressives: “Why can’t you get this done?” Our conversation was basically Harold saying, “David, you and the others have to understand: I cannot do all of this by myself. There are still enormous challenges and a long way to go, and I need the reformers, the progressives, the liberals—I need them to be constantly out there fighting.”

Luis Gutiérrez

26th Ward alderman

He was human, like all of us. He had every frailty that every human being and politician has. But hell if I remember any of them. You wanted him to succeed because you felt he was fighting for you. And when he lost, you felt like you lost. That day, I remember getting a call from an alderman, one of the Vrdolyak 29, and he said, “My guy works at the fire department with the paramedics, and Washington is not going to make it. We should start thinking about how we put together a coalition for 26 votes.” And I hung up the phone. I was so mad. That was the rawness and the crudeness of Chicago politics. The body’s not cold and people are trying to figure out how they gain power.

John Sanders

Senior cardiac surgeon at Northwestern Memorial Hospital

We knew the mayor was coming. We didn’t know what condition he was in. All we knew is that they had needed to start CPR in his office and, as near as we could tell, they had not been able to get a meaningful heart rhythm back. They’d continued CPR all during the transfer. [When they arrived,] the emergency room physician looked at his monitor and said, “We’re not getting anywhere like this. Can you put him on the pump?” Which is short for the heart-lung machine. And we inserted tubing to drain the venous blood out and then reinstill the arterial blood to the femoral artery. That gave us a chance to say, OK, we’ve got a good blood pressure, his brain is getting oxygenated, his heart is getting oxygen. It doesn’t stop the heart attack, but it certainly allows us to assess. During that time, we were never able to get back a strong rhythm. More tellingly, he had no signs of neurologic activity. That was very, very worrisome.

His family members had come to the emergency room, and we were obviously keeping them closely informed. Word got out very quickly, so there were a whole bunch of political figures there who were like, “Keep him alive! Keep him alive! Keep him alive!” We gave the heart-lung machine a good hour and a half to see if it would bring him up to some identifiable level of consciousness. But once it became clear that neurologic function wasn’t coming back and heart-pumping capability was not coming back, my advice to the family was that the most unkind thing would be to keep this going for a long time. We said, “It’s time to turn off the pump.”

Dorothy Tillman

3rd Ward alderman

I was at my office when I got word that Harold had a heart attack, and I went down to Northwestern Hospital. I went by the door to the room where they were working on him, and I will always remember seeing him lying up on that table. We sent somebody to try to find Roy Washington, his brother. [Washington’s fiancée] Mary Ella [Smith] came in, and we all went into a private room and joined hands and prayed. All the inner circle people, some aldermen, were there. We felt he was going to make it. We all were standing around there praying, and we got really tight, really quick. I said, “He’s all right now, huh?” And Mary Ella said, “Yeah, yeah.” At that point, the doctor came in and told us he’d done all he could. I just sat down, because it was surreal that he was gone.

Hermene Hartman

Special assistant to the chancellor of the City Colleges of Chicago

I was totally caught off guard. And I went to Wayne [Watson, the vice chancellor] and I said, “Wayne, I’m going to close the office, and I want everyone to go home,” because I was nervous of riots downtown. Wayne said, “You can’t do that,” and I said, “Well, I’m doing it.” So I started walking the floors and saying, “You can leave work. I want everybody to go home.”

Richard Dent

Chicago Bears defensive end

It wasn’t long before that day that I was with him. Because sometimes on my off days, I would just come down and hang out with him and have conversations in his office, or we went out to lunch. He loved soul food. I tried to get him to work out a few times, but he was like, “I don’t have much time.” He’d always say, “The workout is in the fight. I’m fighting people every day.”

And there was so much fighting back then. Everybody was pissed off. You’ve got to clean things up those first two to three years, then you can begin to do something in that second term. You can’t get much done until you get people to buy in, and I think by his second or third year, people started buying in. Then all of a sudden, boom, he’s gone before Thanksgiving. It was like, Shit. We were thankful for having him, but people were pretty sick because this thing was getting ready to finally take off.

Joan Harris

Commissioner of the Chicago Department of Cultural Affairs

Shortly after his first election, I received a call from somebody who was trying to set up his government and help him with the transition. The mayor wanted to put together a group of informal advisers, a kind of kitchen cabinet. We were unofficial. We didn’t really exist. We met with him maybe once a month for a couple of years, and I think what he wanted was to talk to people who didn’t have anything to gain from being in his inner circle, just people he thought he could rely on. We were a rather interesting group, multiracial. There were a number of people from the African American community, the business community, the lakefront liberals.

He always called me Ms. Harris, and I always called him Mr. Mayor. I loved him and I was very admiring of his warmth, his vision, and his willingness to tolerate the chaos that came from doing things from the bottom up. It was never totally organized, but there was an energy and a commitment among the people who worked for him. [When he died,] it just felt like the bottom had dropped out. It felt like a huge personal loss. We were very quiet and very sad. We had no idea what was going to happen next.

Jesse Jackson

Civil rights activist and founder of the Rainbow PUSH Coalition

I was in Kuwait on the way to Saudi Arabia when I got the word that Harold had died. The Secret Service took me to the side and told me. I cried. I just stopped and wept. When the sun is eclipsed at high noon, there’s disorientation. Chickens start screaming, and nature seems to be out of order. And in some sense, when Harold died, it was like that. There was no preparation for successors, no preparation except to have Harold for some more years. I had to figure out what to do. I was trying to cry and think at the same time. The one thing I did know was to come home. I froze my schedule and said, “We’re going to catch the next plane back home. We ain’t going no further.”

You can win because you’re popular. You can govern because you understand the system. Harold could win and govern. He was a change agent, which is unusual. He said he would break up the machine, and he did, which freed a lot of people up. For the first time, blacks and Latinos had positions at City Hall. Judges could get elected without losing their judicial integrity. People got contracts who never got contracts for business before. And he was not returning fire against whites. So some were like, “I have no basis to hate this guy. He’s delivering.”

Most guys want to keep the rules that got them in. He changed the rules. That’s why today you can become a police officer or firefighter without having to go through your committeeman. That’s why you can run for office because you serve the most people, not because you have the most connections.

Carol Moseley Braun

Illinois state representative

Harold actually saved my political career, such as it was, because I sued the Democratic Party on reapportionment [in 1982]. I won the first verdict outside of the South on racial gerrymandering, and everybody told me I’d just committed political suicide, and that’s when Harold named me as his floor leader in Springfield. So I became assistant majority leader because of him at a time when I’d just won a case against the Democratic Party. [When he died,] it was like a member of your family had died. Everybody was beside themselves with grief. I walked from the County Building to City Hall. They were having meetings in the back on the fifth floor. It was chaos.

Jacky Grimshaw

Director of the Mayor’s Office of Intergovernmental Affairs

Since I had responsibility for the legislators, both Springfield and congressional, my job was to get them on the phone and inform them of the mayor’s passing. So that’s what I was doing, along with my staff. And they were very hard calls to make. I don’t know how I did it. For a lot of that weekend, it’s a blur. I think I was just robotic. I don’t even remember what I said. I don’t think I ate or slept until probably Sunday. I was in tears half the time. I couldn’t stop crying.

As many conversations as I’d had with Harold, we never talked about what would happen if he passed away. So I didn’t know what he wanted. I just felt that this was the greatest man I’d ever known, and we needed to make sure that we did him proud. We had to handle his interment in a way that would [befit] his uniqueness and what he meant to the people of Chicago.

Timuel Black

Historian and Washington adviser

People lost their voice when he died. They lost the confidence and the determination that Harold represented. The coalitions that we had created between African Americans, liberal whites, Asians, and Hispanics had been broken, and each of those ethnic groups had to go out on its own.

He almost had, in his own way, the attitude of a man who might have adopted him and who he adopted, Martin Luther King. There was a great deal of similarity in their styles, in being able to deal with the variety and diversity of people. Always the future was in the dream. That’s the way he behaved, and that’s the way he felt. He had a responsibility, not for Harold Washington, but for the community that he represented.

David Axelrod

Campaign consultant for Washington’s second mayoral election

The saddest thing about his death was that he won the 1987 election; he had crossed the Rubicon. A lot of people thought he couldn’t win it, and he won a solid victory. And by that time, the City Council had turned his way, and there was a sense that, OK, he’s the mayor—this is not a fluke. And he had an opportunity after that to really unify the city and help get us past some of the racial strife that we had seen. That was reflected in the fact that when he died, there was an outpouring from all over the city. It wasn’t just from one part. People had come to think of Harold as representing the city. He used to joke, “When you asked people around the world about Chicago, they used to say, ‘Al Capone.’ But now they say, ‘How’s Harold?’ ”

One of my great disappointments is that Harold died before he really got to know Barack Obama. They had one encounter when Obama was a community organizer. I think they would have been extraordinary friends. I think Harold would have been his mentor. And as it was, the movement that Harold created, the change that he made in our politics, really made it possible for Barack Obama to rise and become a United States senator and, ultimately, president. So even though he didn’t know Harold, he stood on Harold’s shoulders.