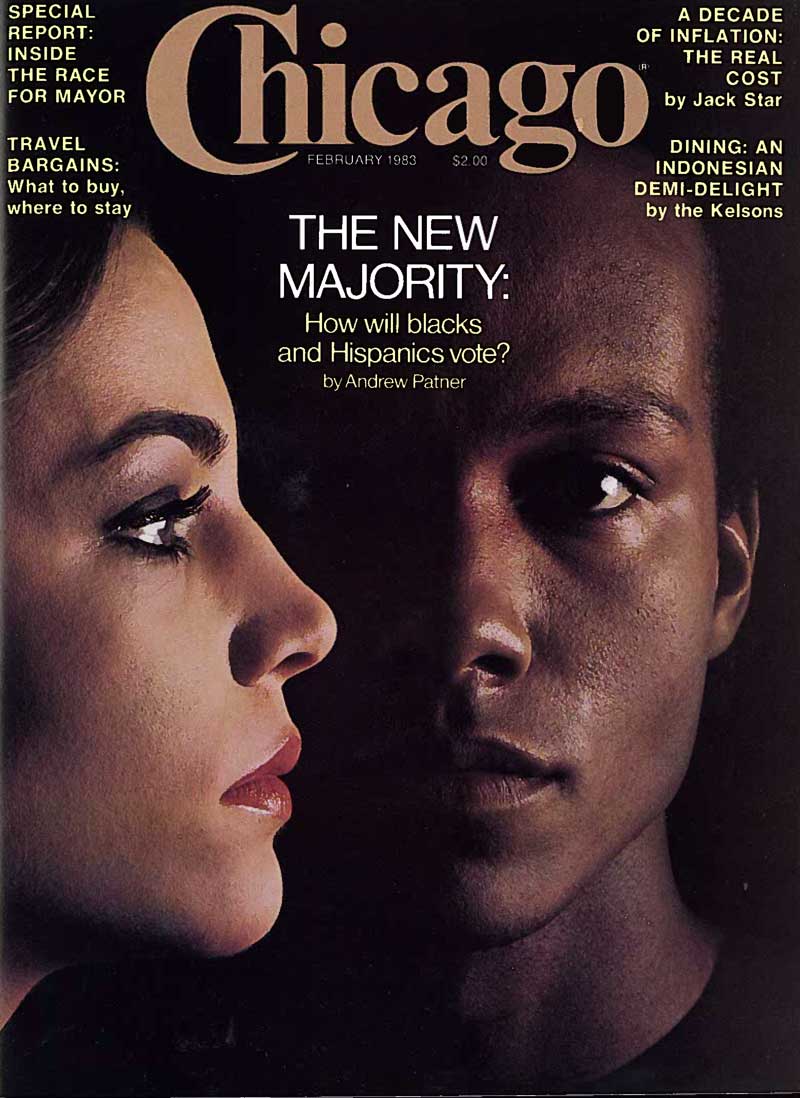

Chicago—from its founding, a city of ethnic politics—has become a city of racial politics. Out of the melting pot, with its generations of immigrants, have come three shades of people—black, white, and brown—who coexist but rarely mix. The city is ruled by a machine that for more than half a century has used the conflicts between these groups as a means to political control, as well as making racial separation an end in itself. But the division of the races that helped build the machine has also contributed to the city's decline. Chicago's major problems—jobs, housing, education, health, and transportation—are problems of race, sometimes explicitly, but always inherently.

While these issues have been discussed in the press, in the courts, sometimes in the, City Council, and certainly in the streets, they have never before been so clearly crystallized. In public debate and in the hidden discussions of power brokers, the theme of this mayoral election is race. Transcending the traditional split between the machine and the independents, and yet bound up with that distinction, is the question: Is Chicago ready for a black mayor?

Since 1935, when Congressman William Dawson led them into the Democratic Party, blacks have been an important force in electoral politics. Under the sway of the Democratic bosses, they elected Richard J. Daley mayor, beginning in 1955, and provided him and his candidates with margins of victory until his arrogance and that of his heirs finally outweighed the pull of the precinct captain.

At first their rebellion was a kind of guerrilla warfare that grew out of the civil rights movement. In the sixties and early seventies, independents A. A. "Sammy" Rayner, William Cousins, and Anna Langford were elected to the City Council from the South Side. During the seventies, black indignation spread beyond the ward level in response to the brutality and insensitivity of City Hall. The defeat of Cook County State's Attorney Edward Hanrahan by Republican Bernard Carey in 1972 after the raid on the Black Panthers, the re-election of Ralph Metcalfe to Congress in 1976 after he broke with Daley over police brutality, and Jane Byrne's victory over Michael Bilandic in 1979—all were achieved because of the massive support of a black community aroused by word of mouth, not organized campaigns.

This changed last year when activists capitalizing on disaffection with Mayor Byrne and Ronald Reagan—as well as on the possibility of a black mayoral candidacy—boosted black registration from 400,000 to more than half a million voters. With Harold Washington's entry into the mayoral race, a second drive was launched to register 100,000 more.

But as the November second election showed, there is no guarantee that those new registrants will vote the way black independents want them to. The dramatic increase in registration and voter turnout played into the hands of Edward Vrdolyak, Jane Byrne, and Charles Swibel as they attempted to consolidate their control of the Cook County Democratic Party. Backing the "Punch 10" slogan in the black community with widespread intimidation and electioneering, the regulars were able to ensure huge Democratic victories throughout the city, carrying for all nominated candidates, retaining all but one judge, and soundly defeating three independent black and Latino candidates for state representative.

Poll watchers for independents Juan Soliz, Monica Faith Stewart, and Arthur Turner received little help from State's Attorney Richard M. Daley on election day. Near West Side precincts got only spot coverage from Daley's office, and on the Far West Side, where gun-toting machine precinct workers had been provided with deputy sheriff's credentials from Deputy Chief Sheriff William Henry, activists could not even get their phone calls for help returned by the state's attorney's office. The news media let vote-fraud stories go by for more than a month and began their coverage only when United States Attorney Dan Webb announced his investigation.

Black strategists now say that they put too much emphasis on registration and not enough on voter education but that things will be different in February, when there is no straight-party option in either the mayoral primary or the nonpartisan elections for alderman. But those who predict a high black vote for Washington may be underestimating the renewed power of the machine and its concern with this election, as well as the draw that the Daley name still has in the black community.

They also might be putting too much emphasis on a tough mayoral race and not enough on organizing aldermanic campaigns that could change the shape of the City Council. Until Allan Streeter's (17th) defection last summer, Danny Davis (29th) was the sole black independent in the council. Two or three of the other 14 black aldermen occasionally split with the Mayor on an overtly racial issue, but otherwise the black bloc solidly supports the machine on questions that determine the fate of the black community. As Tribune columnist Vernon Jarrett has pointed out; independent white aldermen have "voted 'black'" more than any of the black regular party aldermen. Vrdolyak has placed the defeat of Davis second only to control of the, mayoral election on his list of priorities for February.

Latino involvement in city politics has been at once briefer and more complex. Divided geographically and ethnically into several distinct communities, Hispanics have never been able to achieve even the power and unity of blacks. In addition, many Hispanics are recent immigrants or reluctant to become naturalized; only Puerto Ricans have instant citizen status. Hispanics are settled in areas under the firm control of such machine stalwarts as Thomas Keane, Vito Marzullo, and Vrdolyak. The first two Latinos elected to office in recent history—Alderman Joseph Martinez and State Representative Joseph Barrios—are both products of Keane's 31st Ward organization. Perhaps the most important election on the November ballot was the race for state representative in the 20th Legislative District, which marked the birth of the first independent Hispanic political movement in Chicago history. Juan Soliz was able to get one-third of the vote, running on an independent third-party line against the organizations of Marzullo and First Ward committeeman John D'Arco. Although both the Tribune and the Sun-Times endorsed Soliz's candidacy, articles about Soliz appeared only in the Sun-Times's Spanish section.

The black and Hispanic communities make up a majority of this city. But they are not monolithic. They are growing, changing, seeking to come to terms with the city as a whole, and with each other. The speakers on the following pages are not stereotypes—they are not even types. They are black and brown voices that say something about history, that speak of dreams deferred, of hopes and aspirations.

Dorothy and Lavon Tarr

Respectively a teacher in the Chicago public schools and a real-estate developer live in the "Pill Hill" area of South Shore

D.T.: I was born in Henderson, North Carolina, and my parents had no political affiliation, because in the South that was not allowed. My mother's mother came up from Georgia to Chicago because she had boys; she felt that the South was not a place that would provide a long life for them. When we came to Chicago we lived with her. She was a dyed-in-the-wool Republican, an election judge at the time of the Kelly-Nash machine. I was a registered Republican, going along with my family. Now I am a registered Democrat, but I call myself more of an independent. I never vote a straight ticket.

L.T.: I'm from Little Rock, Kentucky, south of Lexington. My father was a farmer. I came up to Chicago in 1951 after high school. My political background is nearly the same as my wife's.

D.T.: In the race between Ralph Metcalfe and Erwin France I was asked to be a poll watcher. I was told to be in the precinct by 5:15 because that's when they voted for everyone who hadn't voted, and I was there to make sure that it was a fair election. We go to church. with France, but I respected Metcalfe because he addressed the issue of police brutality at the sacrifice of his own political comfort.

L.T.: When. I heard about a move for a black candidate for mayor, I thought it was great. We need our chances, just like everybody else. A lot of blacks are qualified to run the city very well.

D.T.: I'd like to see a candidate who is amenable to all segments of Chicago. I would not want to see someone alienate the power structure, the economic structure. Some black mayors can coexist with the business community; Los Angeles is the classic example. But in some cities with a black mayor the economy is not there; look at downtown Gary. When it comes time to vote, I will weigh more than just the color of their skin.

L.T.: I don't think a black mayor gave Gary its trouble. Look at New York. Are you going to lay that on the mayor? The issues are economic. If you drive west on 39th Street, you see that all the industry has moved out of Chicago. We need to give industry a break on taxes, get rid of the head tax.

D.T.: We were the first blacks to move into this community, in 1967. No one ever knocked on our door and said "welcome"; never. And the change in the neighborhood began within three weeks. It didn't bother us.

Our son was the second black in his class at Earhart Elementary School in September 1967, and by March he wondered where all of his friends had gone. It was quite a traumatic experience for him. You see, being middle class, we had tried to shield him, and we instilled in him the idea that he was as good as anybody else. But we didn't explain why we were saying that or what we were preparing him for. I will never forget the night Martin Luther King was assassinated—I had to give Darrell a crash course in racial discrimination, racial hatred. He had to accept in less than a month's time why most of his classmates had moved and what King was all about. When our daughter went there, it had become a middle-class black school.

L.T.: I admired King. I couldn't have taken the punishment that he took, going to jail for what he believed in.

D.T.: I admired him because although he was of a privileged class, he undertook the struggle of the underclass. When our son was just an infant, I sat in front of the television and watched the march on Washington and cried. When he came to Chicago we went to a couple of rallies, but we didn't go to any marches.

I think we are more polarized now. During the sixties the black middle class was accepted. People were saying, "This is the way it ought to be," and there were no hard times. Now we have to cling to each other, because we are not accepted. .

L.T.: If you look at what happened to the Black Panthers, gee whiz, that could happen to any of us now.

D.T.: Growing up in the South, I knew the Negro national anthem [Lift Every Voice and Sing] before I knew The Star-Spangled Banner because it was part of the black society. It was a part of all black assemblies. We looked up to the black professionals in our small town. Educators, ministers.

L.T.: And the post office workers, the people on the railroad. The Pullman porter, he wasn't educated, but he was exposed. He'd come back and share it with his community, his church, his home. .

D.T.: Our family went away to boarding school because that was the only way to get a decent education, My uncles went to the Tuskegee Institute, so I knew of George Washington Carver and Booker T. Washington, Mary McLeod Bethune was the first great black woman I remember admiring.

I just believe that there are certain traditions that we must return to. At our church, for the fourth year, we are going to celebrate the Emancipation Proclamation on New Year's Eve. We are going back to our roots, we are having more family reunions, we are looking within our own family trees for heroes and mentors, and we are talking about the struggle.

LT.: If Harold Washington runs for mayor I would vote for him because he's black and I know he's not going to win. But, I figure, make him look good. He needs that vote.

D.T.: I don't have any preference now. In the past I have gone into the voting booth and opted not to select any candidate. My daughter even asks me now: "Mom, who did you vote against?" It's going to be more than just a black issue with me when the election comes. I want to be allowed the privilege of casting an intelligent vote.

Marie Helen de la Cruz

A data-entry operator who lives in the Pilsen area

I was born in Pilsen, and I've spent all of my life here.

My parents were factory workers, and my father was also a baker. He was from Mexico, but I'm third generation on my mother's side. They never talked about politics they just voted straight Democratic. The precinct runners used to come by to remind my mother to vote, but that was it. When Humphrey ran for President, we had a very serious debate at school and that is what got me interested in politics, So when I turned 18, I said, "I am going to go and exercise my right, my privilege." I also wanted to be a judge of elections. Most of the judges—underhand, under the table they side. I thought it was high time somebody did it the right way. I told the precinct captain that I was young, capable, and bilingual. And the captain, who happened to be white; told me that there were no vacancies, and at that time I was naive enough to believe him.

In the meantime, my area changed from about 40 percent Latino to 90 percent. And the precinct captain was replaced with two Latino cocaptains. Then, in 1976, through no help from them, I got to be a judge here.

I did try to work for the captain, but he had his own workers who happened to be of the opposite sex. You see, the men are workers and the women are judges, and that's not right.

A woman I know, Virginia Martinez [former director of the Midwest division of MALDEF, the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund], recommended that I get involved in the campaign of Juan Soliz for state representative, in November 1981.

When we went around for signatures, we found a lot of people who weren't citizens, but Juan represented something to them. We need to have a citizenship drive in addition to a registration drive. Only then will we get representation. But the campaign was very educational. We had meetings and coffees. People in this community had never met a political candidate before, and here was someone who was accessible to them; he was down to earth.

Why do people vote for the machine? They still believe in the myth that my parents believed in: Democrats protect and help poor people.

It would be wrong for people to assume that Latinos will support Washington because he is black. Some are loyal to him because he supported Juan. But how many black votes did we get? We didn't get anything. I don't support Washington. I think he would end up using us. I lean more towards Daley. Washington made a statement that though we identify as Caucasians, they treat us like niggers, so we might as well vote for one. That's ridiculous. I'm not a "nigger." I don't even use that term.

I believe in coalitions when they unify, but I don't see why there should be a natural coalition between blacks and Latinos. In our community we have the resources; let's use them. I've got my own battles to fight. We need to change our image, that we're all lazy or illegal immigrants. We have to show that we're a force of our own.

Juan M. Soliz

An immigration lawyer and political activist who lives in Pilsen

My family were migrant workers in Texas until I was five years old. Then my parents separated and I grew up in Lovington, New Mexico, on welfare and food stamps. My four brothers and sisters also lived with my mother. In my last year in high school I got the inspiration to go on to college. Before that I'd had no incentive to excel. My mother always insisted that we go to school, but she couldn't help us with our schoolwork. I was poor and I didn't speak English.

In that area of the country, I had dozens of uncles and cousins and no one had ever graduated from high school. I had never had exposure to any successful people; I didn't know any lawyers or doctors who were Hispanics. In college I really started to grow politically. In 1969, I was involved in the antiwar movement, and in the Chicano movement to try to gain our own identity, to become proud of ourselves.

I finished college in '73 and was doing student teaching in Lovington, but I realized that this wasn't all there was to life: coming back to your hometown and teaching. So I decided to go to law school and was accepted by the University of Washington.

I finished law school in '76. I was one of three minority students who passed the bar. I immediately got together an organization, Justice for Third World Students in the Legal System, and we met with the bar examiners and the administration and got a lot of concessions. Then I practiced with Legal Services and was active in the community. In 1978 I came out to Chicago and began working as a staff attorney with the Legal Assistance Foundation. In 1980 I became the director of the Legal Services Center for Immigrants.

I hadn't worked in any political campaigns since the Robert Kennedy and MeGovern races, but then I lost half of my paralegal staff here, when Reagan's budget cuts began to take effect. And at that time the new district maps were being drawn and we started a coalition to fight the gerrymandering. They divided our communities, Pilsen from Little Village, and realistically we couldn't expect to elect anyone. We approached MALDEF to file a lawsuit—and we won and got the first district that was more than 70 percent Hispanic.

I decided to run in the district as a result of several meetings. Of four or five candidates, l was selected as the one most likely to beat Marco Domico. We set out to seek the nomination of the Democratic Party. We needed 600 signatures and we went out in January 1982. After many decades of waiting, we had the opportunity. We filed over twice the number required; then they knocked me off the ballot on a technicality. Although I was a registered voter in the First Ward and in the district, they claimed that they could not locate my change-of-address card, although both addresses were in the district.

We decided to call a boycott of the March primary. It was a very hard decision. We were asking the voters to refrain from exercising one of the most fundamental, constitutional, legal, and human rights. But it was extremely successful. In the First Ward, only about 500 people showed up in ten precincts, out of thousands of registered voters.

Right away we made the decision to go with an independent campaign, and the boycott was a successful litmus test. In two months we got more than 6,000 signatures, and the day after we filed the organization was over them; trying to knock me off the ballot again. But they didn't even file an objection. Three thousand signatures were required, and we got over a quarter of the registered voters in the district.

In the election we got one-third of the vote, 5,000 votes out of 15,000. I didn't think that the organization would be so strong.

In the campaign, I found a lot of discontent. I was fortunate to walk most of the streets in the black areas, and I found that the concerns there are different from in the Hispanic community. Latinos are concerned that we have no voice in Springfield. But in our area, the black community is very poor, the housing is deteriorating, the community is dying, and nobody cares about it. Marzullo, Roti, D'Arco, Domico—they're not doing anything about it.

We did that nitty-gritty walking the streets and organizing. There is no other formula. That's the formula that the machine uses. They beat us. We have a saying, "Uno tiene que saber ganar y perder: You've got to learn to win and you've got to learn to lose." It won't be until we build that same kind of an organization that we can win. We can't do it with patronage, but we have our own resources.

We did very well in the Latino community. We came very close in the First Ward, close to 100 votes. I don't think that in any Latino precinct we lost by more than 40 votes. No one has ever beaten Roti and D'Arco, and we got 49 percent of the vote in their ward, up against the straight ballot on an independent third-party line. That's remarkable.

We haven't lost any workers. The feeling is that we have to consolidate our movement, so we've formed the Independent Democratic Organization of the Near West Side, of which I am chairperson.

I support Harold Washington, and a good part of my organization supports him. But it's important that they recognize that we're not in anyone's pocket. Some of the members of my organization support Daley.

The Latino community is also divided geographically, but we're beginning to recognize that no one is going to benefit from our being divided other than our enemies, who have been successful in keeping us divided. That's the same for us and the black community. At some point we're going to be speaking with one voice. We have differences, but we suffer the same kind of discrimination—high unemployment, bad services, bad housing. Our needs are much the same. I really have hope for the future if we are able to forge unity.

That statement of Washington's is true. I'm sure he meant nothing derogatory by it. In many ways, we are all "niggers." But the reality is that there is racism in both of our communities.

I think we've opened the door and that this is a firm beginning. It hurt me to see men, older men, crying when we lost. But it didn't really hit me until some kids saw me on the street and said, "Soliz, why did you have to lose?" And I wondered, Was I a failure for these kids? I hope to show these kids that it's a lesson for them, too, because they're going to lose many, many times in their lives. But they need a victory soon in our community.

Nate Clay

The news editor of Chicago Metro News and Englewood resident

I was born in Sikeston, Missouri, a little whistle-stop town that was a stronghold of the Ku Klux Klan. I was raised in Memphis, where I became acquainted with classic American racism: the black-white signs everywhere, the separation on buses and in the movies. Emmett Till was killed in 1955, when I was 14, and that had a great impact on me, since I was about the same age. Till was a Chicagoan visiting relatives down in Mississippi who was killed for allegedly whistling at a white woman. When that was being written about, I used to run out and get the papers every day. I was a carrier for the Tri-State Defender, which was owned by the Chicago Defender, and it was the black newspaper down South. The Pullman porters dropped it off at each stop.

My mother was a seamstress and could not get a job in Memphis. They felt that sitting down and sewing was too good a job for a black woman. So in 1959 we packed up and migrated to Chicago. We lived down the street from Marshall High School at Adams and Kedzie, and my mother got a job with Phil-Maid Lingerie. We thought that was a sign of a vast difference; even though in Chicago I was called "nigger" to my face for the first time in my life.

I had heard about the Black Muslims, and when I was about 16 I went to their annual Saviour's Day rally at the Coliseum on Michigan Avenue and was fascinated. I thought Malcolm X had the answers.

I left Marshall High School in tenth grade, in 1960, because I wanted to travel. I joined the Navy for three years and in San Diego I came upon the Muslims again. I began reading the newspaper Muhammad Speaks and going to the meetings where they told us about the idea of black folks having a separate nation and about ancient black history. Before that, I hadn't known that there were once great African kingdoms, that many of the Egyptian pharaohs were black. I didn't know that the idea of free public education for all came from the Reconstruction-era black congressmen. All I knew before that was about Booker T. Washington, and Abraham Lincoln freeing the slaves, and George Washington Carver inventing all of these peanut products.

I didn't officially join the Muslims. I saw that it was a straight-jacketed operation. You had to be noncritical. Although I never rejected the philosophy of self-reliance and self-determination, a lot of the other stuff I dismissed as mumbo-jumbo, The Muslims were divorced from politics, they didn't even vote.

I came back to Chicago in 1964 and worked at the post office for five years. In the black community, a job at the post office was considered a great sign of success, like being a Pullman porter and working on the railroad. They were steady jobs, and people who came through the Depression remembered that people who had these jobs were the only ones eating. There were a lot of college-educated blacks there, a great reservoir of black talent there. I had not been around those kind of people before.

Henry McGee was named the first black postmaster after Bob Lucas organized some postal workers and demanded that a black be hired. When McGee was hired, the white supervisors had a slowdown. I remember being told to take breaks. The mail was stacked up out in the streets!

Mostly, I had been a sideline observer. I was on Madison and Pulaski when the riots started after Dr. King was killed. And I had watched those riots and the protests against the fire department for not hiring any blacks. I wrote in Dick Gregory's name when he ran for mayor. But I wasn't involved in voting politics. It was all run by gangsters. The West Side was the point of disembarkation for poor blacks and Puerto Ricans, and the prostitution. and dope rackets were run by the gangsters with the cooperation of the machine. Blacks were simply the peddlers. The white committeemen who ran the West Side knew about all of that.

I graduated from Roosevelt University in January of 1973 and started graduate school in political science, but I won a Michelle Clark scholarship to Columbia University's journalism school. The program grew out of the Kerner Report. One of its recommendations was that the media needed to train and hire more blacks. During the riots, the Tribune didn't even have anybody to send out to the West Side!

I started working for the Defender in 1975, and I started my column, "Clay Images," in 1977. I was just a working journalist, not the Lu Palmer type. Then I went to PUSH for two years and we had some hot political issues then. Jesse Jackson had supported Jane Byrne, and then she embraced those she had attacked.

There is a white woman who is mayor of Houston, Texas. She came into office with the black vote, the same as Jane Byrne did. One of the main issues in Houston was police brutality, and one of the first things that she did was hire a black police chief, Lee Brown, who had been safety director in Atlanta and one of the finalists for the police superintendent's job in Chicago. Now, in Chicago, Sam Nolan was the number-one man in the department, but Byrne passed over him saying she wanted an outsider. But then she selected Brzeczek—a white insider.

The Board of Education had similar problems. Manford Byrd was sitting there patiently—he should have been superintendent in 1979 when Hannon got the job. I was spokesman for the Manford Byrd Committee when Hannon left. It was not that we said that Ruth Love was unqualified; it was simply a matter of self-determination, of self-respect. Bringing in an outsider was clearly a move to bring in someone who could be controlled.

The campaign for a black mayor, like all movements, is incremental. They're not revolutionary, they're evolutionary, sometimes in indiscernible ways—so that when something appears to be an explosion, it's not; there was seething beneath the surface all along. What's happening in electoral politics is the riots, reincarnated. There was a riot at the polling place November second. This is what was happening in the sixties in the streets. But we lost some good independents: Soliz, Monica Faith Stewart, Art Turner—to have somebody like an Ozie Hutchins replace Art Turner is an abomination. But the black people who registered at the unemployment offices and public aid offices, who signed up at Cook County Hospital, did so out of anger at the Republicans. They were out to send a message; they were not out to make any fine distinctions.

The motive this time. will be different from Hanrahan or Byrne's election. This time it's not indignation so much as pride. The voters will be out to get Byrne, too. But the main thing is: We've got our chance now. It's not just going to be a negative vote.

If Harold wins, you'll see a reversion to the strong council system. In Gary, they passed ordinances to take away some of Hatcher's power. But when you have crass machine politicians, their only philosophy is, as Mike Royko says, "Where's mine?" And they will switch bandwagons tomorrow.

But they'll try to make a deal with him if he wins, to convince him that unless he makes certain compromises they will oppose him. He's a very shrewd man and he knows how to work with the organization, but not to the point where he'd be another Jane Byrne.

John H. Stroger, Jr.

A Cook County commissioner who lives in South Avalon Park

When I was in high school in Helena, Arkansas, I worked with a black businessman who was urging blacks to pay the poll tax so that they would be eligible to vote. In Phillips County, there was a predominantly black population but they were not active in politics; the poll tax was the last thing that stood in the way.

I used to read about Congressman William Dawson from Chicago, and I even heard him speak when he came through Arkansas during the Truman campaign. I admired his organizational ability and his oratorical skills. I used to read various black periodicals: the Pittsburgh Courier, the Chicago Defender—they all came through.

After I graduated from Xavier University in New Orleans, I went back to Arkansas and I taught school for a year in Hughes and associated myself with Shepperson Wilburn, who is now a judge in Memphis. I acted as his clerk when he was preparing a suit against the school district there to force equitable funding of black and white schools. This was before Brown vs. Board of Education. At the end of the school year, my mother decided that my future would be better in Chicago.

I came up in 1953. About the first thing I did was to go to meet the late Ralph H. Metcalfe and join his Young Democratic Organization. I walked that summer in the Bud Billiken Parade as a Third Ward Young Democrat.

I was president of the Young Democrats in 1954-55, and Harold Washington became president after that. I learned a lot from him, but I learned most from Metcalfe.

I had moved out of the Third Ward in 1959, but I still worked with Metcalfe's organization. In 1966 I started to get more involved in the Eighth Ward in Avalon Park. Joseph P. McMahon, the committeeman, brought me into his office. In 1967, he moved from the ward, which was changing racially, and I was appointed acting committeeman. In 1968 I was formally elected committeeman.

In 1970, I went before the slatemakers and asked to be a candidate for the Board of Tax Appeals. And when Mayor Daley put the ticket together, I was slated for the County Board of Commissioners and I've been on there ever since. In the 1870s there was a black man named John Jones on the County Board, and then again in 1938, Edward Sneed from the Third Ward served, and then Kenneth Wilson and former Alderman William Harvey were on the board.

Ed Hanrahan was riding high as a Democratic politician until the Black Panther incident, and most people were shocked and outraged over that. Some of us asked to put up another candidate, but Hanrahan won the primary, so the party supported him. But people in my ward, for example, just went out and voted unbelievably heavily against him.

I instructed my captains not to push Ed Hanrahan and not even to push straight Democratic voting. When the whole community is up in outrage, that would have been stupid. We put great emphasis on all the other Democratic candidates. The whole Black Panther situation was repugnant to me, and I fought to get the county to accept some kind of settlement, and I voted against continuing to pay lawyers high fees when they could have been working on a settlement. It was my notion that we make the settlement that we finally reached in October.

I will speak out when there is something that needs to be addressed, but I support the regular organization candidate. When Bilandic ran in the special election, I supported him, not Washington. But I asked Bilandic in the slatemaking session and insisted that they work out a settlement with the Afro-American police association.

As far as the current mayoral race, I've supported Daley from the beginning. When nobody else was going to his affairs, I was there, because I was turned off on Jane Byrne. She had not been sensitive to my organization or to our community. The more Alderman Marian Humes criticized her, the more difficult she became. I didn't like the manner in which she tried to block Daley's nomination for state's attorney. From there on it was personally downhill. She's turned off on our political organization because our alderman is a very outspoken person. And I supported the alderman. I didn't like Byrne's appointments to the school board, the way she manipulated Eugene Barnes off of the CT A, the closing of the Jackson Park el, or her lack of sensitivity to the problems of the neighborhoods.

It seems as if there is a design in this city to polarize the races. I would never be against the idea of a black being mayor, if a person is black and he has all of the qualifications and the broad-based support to finance and run an election. He could run this city as well as anybody else. In the current election, no black had surfaced when I decided that I had to take on Jane Byrne and get new political allies.

My allies are President George Dunne, Tom Hynes, and other people who were against Jane Byrne. No one ever has asked me to be a part of the drive for a black mayor. I attend PUSH meetings, so I knew that Reverend Jackson would like to see a black mayor, and I supported the voter registration drive, but no one had surfaced to be a candidate.

I had been talking to my captains about Daley all of the time, and I had exposed him to them. The only person who has differed—and she is not a captain, or an officer—is Alderman Humes, and she said we should be supporting Washington. I told her that our organization had remained viable because of our association with Daley and Dunne and Hynes, and that I thought it would be a breach of my credibility to not stick with those people. But I'll support her for alderman; I'm not petty.

People have attempted to criticize Mayor Daley on race, but racism existed in this city and this country way before Daley was born. Under Mayor Daley's leadership, blacks got a chance to participate more actively in city and county government than ever before. When I first came to this city there were no black judges and now there are almost 30 on the Circuit Court. Daley even used his influence to get a black named to the U.S. District Court. He first had the idea that a black hold elected office in city government, and that was Joseph Bertrand as city treasurer.

The social ills that plague big cities reduction of the tax base, the shift to the suburbs, crime—go back more than 25 years, go back before Mayor Daley. The problems of the cities—Charles Dickens and Victor Hugo wrote about them, and they weren't talking about racism.

Many blacks will support Daley, based on his performance and on the Daley name. But he won't serve, as long as his father did. There will be a black mayor—it's inevitable.

Richard L. Barnett

A postal worker and West Side activist from Lawndale

I was born in Chicago and raised in the Second Ward on the Near South Side. My parents were from Coleman, Georgia—I'm the seventh of 14 kids. My parents came up in 1922 just to get away from the South. My father worked in the steel mills for a few years. When the Depression hit, he lost his job and then he got odd jobs. After that he worked in policy. He was what they call the pick-up man. At that time it was honest; that was before the syndicate took it over. Policy used to be the black stock market. It was black owned and operated. They had drawings just like the Illinois State Lottery; in fact, that's where the lottery is from.

We all went to work at a very early age. We lived on 40th between Cottage Grove and Langley. Democratic politics started up in the black community when I was a kid. Blacks were still voting Republican and Dawson switched us over in '35. Until I was ten years old, in the black community there was a two-party system, and it's hard to make people realize that blacks used to vote 98 percent Republican!

Politics has always run the black community. When you get people who are worried about survival, their expectations aren't that great, and the black community and other minorities have always depended so much on promises, that pie in the sky. I don't know whether it goes back to religion or just what. What happened in politics then was the same old money game that they play now: money and favors, very little service. We were much-better-off with policy than politics.

I worked at a grocery store from when I was seven until I was 22 and went into the post office, in 1953. I've been there ever since. The Federal Government was practically the only place that provided jobs for blacks, especially those who were upwardly mobile. There were a lot of college-educated blacks in the post office, the Veterans Administration, Social Security. You could get a decent salary, though below private industry, and also the security of not being the last hired and the first fired.

Antidiscrimination orders didn't even come into the post office until the sixties. I remember that Bob Lucas and some of us from CORE [the Congress on Racial Equality] picketed for black supervision because we were 80 percent of the work force of 20,000 in the main post office, and less than one percent were in supervisory positions. Lucas was fired for that.

I moved to the West Side in 1952. I was married and I had two kids. Once I moved west, I got really involved. In June of 1952 there were kids playing around my building and I said, "I'll manage your baseball team." I managed that team for 18 years, two group—nine-to-12s, and 13-to15s. Two years later I helped to form the Greater Lawndale Athletic and Civic Association with grassroots people in the community, and we ended up having 16 teams of boys in each age group. We got the idea that if we could deal with them on race pride, community pride, respect for property and education but mainly respect for self, we could talk to them about the fallacies of gangs.

During the 18 years that I had that team, I had only two high-school dropouts. Most of these boys went to Farragut High School, where the dropout rate was 70 percent. I had everyone of the youngsters believing that they were all going to college, even though I knew that they weren't all college material. But I felt that if I could put that into their heads, that would keep them from dropping out of high school.

I didn't see myself getting involved in politics until 1957. Our ball team had got permission from the Kuppenheimer company, at 18th and Karlov, to use a field behind their plant a block square. We cleaned the lot with all of the neighbors' lawn mowers, but it was still just hills and gullies and it needed grading. We went to Alderman Ben Lewis in the 24th Ward and Alderman Janacek in the 22nd Ward because the land was on the border. We asked if the city could bring in a grader, and after a long rigamarole they said that the city couldn't afford it. And the day after that, the queen of England came to Chicago and Mayor Daley put in a block of brand-new curbing on Michigan Avenue. That blew my mind, because here the city could spend $18,000 for two blocks of curbing and couldn't spend $300 to grade that field. From then on I said that politics controls our community.

I got involved in Arthur Hamilton's independent campaign that year, for alderman of the 24th Ward. Sidney Deutsch had been the alderman, but when Daley appointed him city treasurer we had a vacancy. The ward was now all black, so they knew we needed a black alderman and they chose Ben Lewis over Hamilton, who was also a member of the organization. Lewis used to chin and grin. Even when he won as alderman, the precinct captains—90 percent of whom were white and lived outside of the ward—would call him Ben and he would call them Mister.

In the Hamilton campaign there were only 50 of us, all young black novices, who didn't know a darned thing. The machine defeated us two to one. But everyone else the machine was defeating 15, 18 to one. We were a bunch of young idealists trying to work within the system.

After the Hamilton campaign, we tried to keep the group together, but the machine gave jobs to 45 of our 50 chaps. They explained accepting the jobs by saying that they could do more from within. When people tell me that now, I look at them as if they're questioning my intelligence, because those 45 people that they bought went inside of that machine and became the machine. That's who's in the 24th Ward now.

In the election for dull aldermanic term in 1959, we got a chap to run named Whitehead. We went out in the cold to get his petitions signed, which we filed. But unbeknownst to us, he went down and withdrew his candidacy. It wasn't that they offered him a job—they told him that they would break his kneecaps.

From '64 to '67 I stayed mostly with baseball and Boy Scouts and volunteered two years at Blessed Sacrament School as a physical fitness instructor. I had been in CORE since the early sixties, and I was in all of the marches of Chicago. I was involved with the "Endslums" campaign when Dr. King came and stayed at 16th and Hamlin and Andy Young was the minister at the Warren Avenue Baptist Church at 3100 Warren. I eventually had to leave that, as far as the nonviolent stuff was concerned, because I found that the older I got the less I was able to peacefully accept someone throwing something at me or spitting on me.

In 1967, a group of us got together and tried to run Republican ward committeemen in all of the West Side wards. Stanley Kusper was counsel for the Board of Election Commissioners and he knocked off everyone of the candidates on technicalities. They didn't want anyone getting into the Republican Party—they would have been able to appoint judges and get control of some polling places. You see, when the polling places closed at six o'clock, you didn't have half Democratic and half Republican judges. You had five Democratic judges and a precinct captain. There was no check and balance. The cop and everyone else were always in on it, too.

Jesse Madison ran for state representative on the West Side in 1972 and he lost by 3,000 votes, but we had 49 judges indicted for vote fraud and it was estimated that they had stolen 3,300 votes. In 1973, Alderman Biggs died and we had a people's convention in the 29th Ward. Each block club could send two representatives and each community group could send one. We had 168 delegates, and 127 came to the all-day Saturday convention. Cliff Duwell White was nominated, and for the first time in West Side history we took the machine to a run-off in an aldermanic election. Once Cliff got into the special election on June fifth, Mayor Daley put some stuff in the game and made the run-off July third, knowing that many people would be going out of town and that if you worked, you couldn't take the day before the holiday off. Cliff lost by less than 25 votes a precinct. And from the nucleus of that convention, Jesse Madison ran again for state rep in 1974 and won by 174 votes. In '76 he won re-election by 2,595 votes.

Also in 1976, for the first time in West Side history, the machine lost in a one-on-one vote. The state representative race was in a three-way contest, with bullet voting. But Earlean Collins won the senate race by 62 votes. They had never been defeated before. We had placed 107 honest judges of election, one in every precinct. All of a sudden, in the 24th Ward, which had been voting 16,000 to 18,000 in every election, the vote count went down to 12,000. That meant 5,000 votes had been ghosts. One honest person in a polling place can change the whole complexion of an election.

Danny Davis had the best campaign I'd seen since Anna Langford. He gave up an offer of a health job in Detroit for $50,000 to run for alderman in 1979, in the 29th Ward. First we got into a run-off and then we took the seat. This was the first independent alderman elected on the West Side. In 1978, Jesse Madison did not seek re-election, and a citizens' search chose Arthur Turner to try to keep Jesse's independent seat and he lost by about 1,000 votes. Lots of fraud, but nothing we could prove. But building on Danny's group, Art ran again in 1980 and won.

After we went to single-member districts, Turner lost in March 1982 due to fraud and hoodlumism. They brought out the gangs, and intimidation was rampant. In the November election it was the same thing, plus we were up against "Punch 10." We had a chap who had to get the whole right side of his face reconstructed after a beating for putting up posters for Art Turner. It was the greatest fraud that I'd seen in 20 years. When Carey was state's attorney from '72 till 1980, he cut vote fraud down by 80 percent. Richie Daley came into office and it was just like having a closed door. That's why the U.S. attorney is going to find so much stuff there: The state's attorneys did nothing.

Washington will have a very tough campaign because there are a certain number of people in the black community that Byrne and Daley can buy. They are invited to every event in the black community, and Washington is not invited to a single event in the white community. A lot of blacks misconstrue what Daley is about. He wants to rebuild the political power that his father had. But he has an eight-year record in the state senate that he has to run on, and most legislation, that would uplift blacks, minorities, or women, he voted against. People are attracted to his name. Their expectations were so low under his father that when they got a little, they were grateful. He gave people the perception that he really was interested in people's welfare, especially poor people.

Unless we can start with our young people, we're going to stay in the same bag that we're in now—the patronage bag, the "I've got mine, you've got yours" bag. Our young people really have to be educated, and then they have to return to their community and serve the way Art Turner did. Art said that he would give ten years to his community after he got his degrees. We don't need any dummies and we don't need this whole lost generation; that's what The Man preys on. That's what the Byrnes and Daleys hope to cultivate: a low level of expectations, a lack of education. And if those things happen, people are just useless and bitter. When you're worried about survival, you don't care who your President or your ambassador or your state representative is. And that's just the way they want it. Sometimes I think I should just go back to baseball full-time, to working with young people to develop their self-respect and their talents. That's the only hope for our community. I have to keep moving; I can't say what other people should do. If I'm to be free, it has to start with me. It's pure and simple.

Comments are closed.