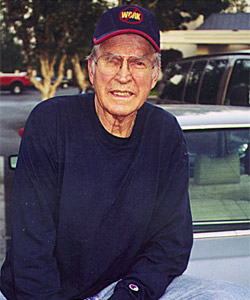

Far from Chicago: Nazi sympathizer Herbert Haupt (center) and his friend Wolfgang Wergin (left) travel by freighter from Japan to France in 1941.

Under a clear night sky on June 17, 1942, the German submarine U-584 surfaced just off a sandy Florida beach 30 or so miles south of Jacksonville. Four young Nazi agents scrambled into an inflatable raft and paddled ashore. Among them was Herbert Haupt, the 22-year-old son of a German American family on Chicago’s North Side and a former student at Lane Technical High School. Along with his three colleagues on the raft and four other Germans who had already been dropped by another sub on Long Island, Haupt was part of a terrorist team—a band of saboteurs armed with explosives who planned to blow up U.S. bridges, factories, and even department stores.

Haupt and his companions watched the sub’s conning tower slip back into the Atlantic, then buried their cache of weapons in the white sand. After lying low until morning, they caught a bus to Jacksonville. From there, they scattered to predetermined destinations, with orders to blend into American life before gathering again a few weeks later to start their violent campaign.

Haupt headed home. He rode a train to Chicago’s Union Station and grabbed a cab. For eight days, he resumed the Chicago life he had left a year before—living with his parents on Fremont Street, seeing relatives and friends, reconnoitering with his girlfriend. His dad bought him a car, and he prepared to return to his old job at an optical factory. But on June 27th, Haupt’s Pontiac coupe was surrounded by FBI agents near a North Side el stop. He was arrested and charged with sabotage. By the end of the day, all eight of the Nazi terrorists were in jail.

Their arrest opened the way to a startling episode in the history of American justice—one that is directly relevant today. Haupt was sent to Washington, D.C., where he was tried in secret by a military tribunal, one of the last held on U.S. soil. Convicted with the others of war crimes, he was sentenced to death. He was not allowed an appeal. The only review of the case was by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. The President didn’t even announce the verdict publicly until after Haupt and five others had been executed.

The case didn’t stop there. Haupt’s parents, his aunt and uncle, and the parents of a friend—all German Americans living in Chicago—were also arrested and charged with treason, based largely on the fact that they had not turned Haupt in when he reappeared. With the national mood intensely hostile to Germany, the six were convicted after a high-profile trial in federal court in Chicago. The three men were sentenced to death, the three women to 25 years in prison. Eventually, an appeals court overturned the convictions, and only Haupt’s father stood trial and was convicted again. He and his wife were both deported to Germany after World War II.

Though Herbert Haupt was portrayed at the time as a fanatic Nazi and dangerous saboteur, today it’s not clear whether he really intended to carry out his mission. One companion, who has never before spoken out about the case, says that Haupt simply wanted to escape Germany and return to his prewar life in Chicago. Most evidence suggests he ended up in Germany only as a result of a youthful adventure that went awry. It is even less clear whether his parents and others charged with treason were guilty of anything more serious than harboring the young man.

Years later, even some of the U.S. Supreme Court justices who upheld the constitutionality of the secret trial of Haupt and his coconspirators came to regret the way the decision was made. Still, the case has been cited as a precedent by President George W. Bush, who announced last November that suspected terrorists linked to Osama bin Laden might be tried by secret military tribunals. Bush and U.S. Attorney General John Ashcroft have said that foreign terrorists who commit war crimes against the United States do not deserve the usual protections of the U.S. Constitution.

There are countless differences between the circumstances of Haupt’s arrest and trial 60 years ago and the aftermath of the September 11th terrorist attacks on New York and Washington. Among other things, the Nazi saboteurs never blew anything up. But in both instances, the original missions involved well-planned terrorist attacks by foreigners. The 2001 terrorists went after symbols—of commerce and the government. The Nazi saboteurs were more practical—they wanted to strike at targets that would hurt the U.S. war effort and demoralize Americans.

Legal scholars point to the saboteur case as an example of the sort of swift justice that President Bush has in mind. That World War II prosecution pushed the American legal system into territory that the country has dared not re-enter—until today. If nothing else, the case shows how established principles of justice can, under certain circumstances, be easily transformed.

As it turns out, Herbert Haupt bears a number of superficial similarities to some of the men linked to the September 11th terrorist attacks. He was young, he came from a stable family, and for a time, apparently, he was an ardent believer—in his case, in the glory of Germany. He may or may not have been a devoted Nazi at the end. What is almost certain, though, is that when he started on the journey that would turn him into an accused saboteur, he never imagined where it would end.

* * *

Wolfgang Wegrin

Wolfgang Wergin is 79. Age and injuries have whittled at the hulking six-foot frame he enjoyed when he first met Herbert Haupt around 1940, while the two of them were working at the Simpson Optical Company on Chicago’s North Side. Haupt was three years older, but they hit it off—among other things, they both had been born in Germany and raised in Chicago, though Wergin says he never paid much attention to the German chauvinism that flourished among some German Americans. And he says he never heard Haupt go on about the fatherland.

Rather, the two were mostly interested in fun. “Herbie was a sharp dresser and attracted women,” recalls Wergin over lunch at a casual restaurant in San Pedro, California, where he had retired. “One thing he could never get off his mind was women.”

Haupt also had a wanderlust. In the spring of 1941—six months or so before the United States entered World War II—he persuaded Wergin and another friend to go with him to Mexico. A year later, the U.S. government argued in its case against Haupt that he had traveled to Mexico with plans to go on to Germany. (Haupt gave other reasons in his testimony.)

Wergin, who has never spoken publicly before, has another explanation for the trip’s inspiration. “We went together one evening to a fiesta on the North Side,” he says. “Music. It was real nice. We got to talking. We both had vacations coming. I guess Herbie said, ‘Why don’t we go to Mexico?’”

They set off in Wergin’s 1934 Chevrolet with about $80 each. “Here were two kids from strait-laced families, off on the adventure of their lives,” recalls Wergin, whose side of the excursion would land him more than two years on the Russian front as a German soldier. “The hairier it got, the better it got.”

* * *

Photograph: Courtesy of Wolfgang Wergin

Herbert Haupt was born in Stettin, Germany, the son of a bricklayer, Hans, a veteran of the German army in World War I. Soon after his discharge, Hans had married Erna Froehling, and on December 21, 1919, their first and only child, Herbert, was born. Searching for a better life, Hans sailed to the United States in 1923 and made his way to Chicago. Erna and Herbert joined him two years later. Hans worked on and off as a contractor and painter during the 1920s and 1930s. He applied for citizenship in 1928 and was naturalized in 1930, which made young Herbert an American citizen, too.

Herbert attended Waters Elementary School and Amundsen and Lane Technical High Schools, all on the North Side. “In grammar school he had an excellent record but in high school he preferred earning money to studying and took over six years to graduate,” Erna later told the FBI (though actually, Herbert never did graduate). After high school, he worked at Simpson Optical, earning $25 a week and turning the money over to his father.

Despite having become an American citizen, Herbert’s father, Hans, stayed connected to Germany—a simple matter, given the large number of German Americans in Chicago. He was a member of the German World War Veterans and the Schubert Liedertafel Singing Society, among other German groups. Herbert apparently adopted his father’s passion and became a supporter of the German-American Bund, a U.S. organization that backed Hitler and Germany during the 1930s and 1940s.

Because of hostility to German Americans during World War I—when, among other things, the frankfurter became the hot dog, and, in Chicago, German Hospital was renamed Grant Hospital—many Americans of German extraction had learned to temper their displays of enthusiasm for the old country. But the Bund, with 20,000 members in the United States, broadcast its support for the Nazis in public demonstrations. Herbert Haupt joined in.

“I can picture him now, goose-stepping down Western Avenue in front of the Queen of Angels Guild Hall in his brown-shirt uniform,” recalls Herbert’s boyhood friend John Giannaris, 79, who now lives in Mount Prospect. “It was unusual for kids, even in our German neighborhood, to be so in love with Germany. I would call him fanatical.”

As the war approached, several friends recall, Haupt declared that Germany was superior to the United States. One acquaintance, Lawrence J. Jordan, punched Haupt in the nose at a dance party after Herbert preached Nazi propaganda. Haupt later got back at him, using Jordan’s name on a forged draft registration card when he returned to Chicago.

* * *

Around the time that Hitler was launching his attack on Russia, Haupt and Wolfgang Wergin finalized their plans for the trip to Mexico. At a farewell party, Haupt spread out a map on the floor and traced his possible route. He had not revealed to his family another reason for leaving town. At his trial, Haupt testified that he had wanted to end a relationship. “I was associating with a girl named Gerda Stuckmann and my folks objected to my going with her, and her folks objected to her going with me, because I was younger,” Haupt said. “She became pregnant and I didn’t know what to do, so I talked to two friends of mine and left for Mexico.”

Haupt was 21, Wergin 18. The friends stopped every night along country roads to make a campfire and eat beans, then crossed the border at Laredo, Texas. (The third young man turned back before Mexico.) A few days later, Haupt and Wergin arrived in Mexico City and, according to Wergin, met up with two Mexican sisters. It didn’t take long for the Americans to spend their money. Wergin recalls that the sisters brought their entire family along on a date, which obliged the young men to buy rounds of drinks for everyone. “We lost a lot of money there,” Wergin says. “We kind of snuck out.”

Broke, Wergin sold his car, and the two bought train tickets back to Nuevo Laredo for their return to Chicago. However, Mexican border authorities refused to let them cross until they paid tax on the car—money the two did not have. “Just to show you how dumb we were, we could have gone down the river and crossed over,” Wergin says. “Nobody would have known the difference. [But] we were law abiding kids.”

Back in Mexico City, acquaintances steered them to the Pacific Ocean port town of Manzanillo, where they might find a freighter that would take them to California. On his own, Haupt apparently started formulating a new plan. At his trial, he said he met a man from the German Consulate, who suggested that the two Americans head to Japan, where they could find work.

On July 26th, Haupt and Wergin boarded a Japanese freighter, ultimately bound for Yokohama. Wergin thought the ship would stop first in California to pick up scrap metal, and he planned to get off there. But two days into the journey, Wergin says, he and Haupt got word that the boat was heading directly to Japan. In a letter to his mother sent before the ship embarked, Haupt seems to suggest that he knew the ship wouldn’t stop in California. “He must have kept it a secret from me because he knew I would have never gone along with it,” says Wergin, who was shaken to learn after 60 years that his friend may have tricked him.

But why Japan? One explanation is that Haupt had plans to return to Germany. Before Pearl Harbor, Japan was one of the few entry points into Nazi Germany open to Americans. Nonetheless, after arriving in Yokohama about August 24th, Wergin says, he and Haupt traveled to the U.S. Consulate in Tokyo in search of a way back to the States. Officials there said they couldn’t help the hapless adventurers. At his trial, Haupt said he made contact with the German Consulate, which helped them find work on a German freighter in Kobe. Haupt and Wergin spent three weeks in training before sailing eastward—toward an unknown destination on an unmarked German freighter. The journey, around South America’s Cape Horn, took months. Four days before the ship docked in Bordeaux, in German-occupied southwestern France, the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor. On the day the freighter docked, Germany declared war on America.

For three days, Haupt and Wergin were kept on board ship as German officials tried to determine what to do with the Americans. Finally, when officials realized the two had been born in Germany, they were sent to internment camps and then to the homes of their German relatives—Haupt to his grandmother’s place in Stettin (now known as Szczecin, Poland), Wergin to his grandmother’s in Königsberg (now Kaliningrad, Russia).

Today, Wergin says he was too naïve to be upset by the turn of events. “This is what I was living for,” he says. “I had been so cooped up all my life, wanting to do all these things I saw in the movies. This is what I wanted, and now, finally, I was having it.”

A few weeks after Haupt arrived in Stettin, a German army lieutenant named Walter Kappe contacted him. Kappe had spent 12 years in the United States, including several years as a journalist on Chicago’s German-language paper the Abendpost, but he had been forced to leave the country in 1937 because of his ardent Nazi sympathies. In Germany, he rose quickly through the army by positioning himself as an expert on the United States. “It was an ego thing,” said his son years later. “He was misguided and looking for a chance to be somebody.”

Lieutenant Kappe was masterminding a grand scheme for the Abwehr, Nazi counterintelligence—a sabotage mission against the United States staffed by young men who knew their way around Americans. Apparently, the lieutenant had been notified about Haupt’s long journey to Germany. They met twice, and Kappe signed him up. Haupt later testified that he had had no choice but to join—he had understood that his life and the life of Wergin would be in danger if he didn’t.

“When I saw [Kappe the second] time, he asked me if I knew that my mother’s brother was in a concentration camp and my father’s brother had been, and I answered in the affirmative,” Haupt stated at his trial. “He asked me if I hadn’t noticed that I couldn’t get a job and whether or not the Gestapo and police had been bothering me, which they had. He pointed out that the only thing left for me to do was to return to the United States.”

The mission’s goal was to blow up key installations—huge manufacturing plants, particularly Alcoa factories that produced aluminum for U.S. warplanes; bridges, such as the Hell Gate Bridge connecting Queens and the Bronx; locks on the Ohio River; the hydroelectric plant at Niagara Falls; and railroad tunnels. Kappe also wanted to plant bombs in major department stores owned by Jews.

The idea was to impede the war effort and cause public panic, but the ultimate strategy was more subtle and far-reaching. In a 1959 book about the case, George J. Dasch, the leader of the saboteurs, said the bombings were “designed to inflame the American public against people having any possible connection with Germany and the Axis countries.” The public anger, the Nazis hoped, would “produce a bond among those cast out and vitalize a real Fifth Column movement in the United States.” (Similarly, some analysts have argued that Osama bin Laden’s aim in the September 11th attacks was to provoke the United States into a harsh response that would in turn rouse Muslims throughout the world.)

In April 1942, Haupt began training at the High Command’s Sabotage School near Brandenburg. He was taught how to use detonators and explosives. He and his colleagues were taken on trips to German factories to learn their most vulnerable spots, and they were taught how to communicate back to the Reich.

During his training, Haupt managed to contact Wolfgang Wergin, and they met one last time. “He told me about this thing he was going through, the saboteur school,” Wergin recalls. “He said that he was going to land on the beach and disappear. I told him, ‘You can’t get away from the FBI. They’re going to catch you and stick you in jail.’ I didn’t even think about execution. He said, ‘I’m just going to go and disappear.’ After a couple of hours—it’s toward the evening and we were talking a lot—he started to cry. For all our time together, he always acted as the older one and I acted as the younger one. But on that night, our roles changed. I remember how much he cried.

“Herbie just wanted to get back to America,” Wergin says.

Haupt apparently had trouble gaining the respect of his seven fellow saboteurs. He was by far the youngest, and he was gregarious, wore showy jewelry, and talked in American slang. “The others thought him too frivolous for a project as serious as this, and it was hoped, even suggested, that Kappe not send him to the States,” wrote Eugene Rachlis in his 1961 book about the mission, They Came to Kill. “Kappe invariably replied that Haupt’s physical capacities—he was a muscular hundred and ninety pounds and nearly six feet tall, and had had boxing lessons—made him an asset.”

Kappe’s eight saboteurs were split into two groups of four each. Haupt was placed on Edward Kerling’s team, which included Hermann Neubauer, who had lived in Chicago during the 1930s. That team boarded the sub in France on May 26th. Dasch led the second team, and it included Ernest Peter Burger. Both had lived in Chicago. That group left on another German submarine two days later, but arrived at their Long Island destination earlier, on the morning of June 13th. All the saboteurs were equipped with special James Bond–like devices: a fountain pen–and–pencil set that doubled as explosive fuses, a pocket watch that could be used as a timing device, and small bombs disguised as coal bricks. They were also issued a handkerchief with the names of their U.S. contacts etched in invisible ink.

Dasch never intended to carry out the mission, however. In his book Eight Spies Against America, he said he turned against the Nazis because he loved America. “From the very moment I set foot on shore my intentions were clear and consistent,” he wrote. Once in New York, he and Burger made plans to reveal the plot—after they had given other saboteurs a chance to come forward, too. “In particular I thought of Herbert Haupt,” Dasch wrote. “I felt his return to Germany had been something of a boyish lark and he had ended up trapped, just as I had. . . . I felt he wanted more than anything else to come back to his country and his family and would never go through with a plot to harm the United States.”

Dasch recalled an incident in Berlin: “Haupt and I had been sitting in a restaurant together when a group of SS men came in and gave their stiff Hitler salute. To my surprise and pleasure, Haupt remarked, ‘George, take a look at those dirty bastards.’ . . . [N]o good Nazi would have expressed such feelings and I felt Haupt had shown himself to feel pretty much as I did. Before I would put the finger on him now, I wanted him to have a chance to show his own true colors.”

Several days after arriving in New York, Dasch took a train to Washington to see J. Edgar Hoover, head of the FBI. At first Dasch was dismissed as a kook, but after he opened his suitcase and displayed $84,000 (the two sabotage teams had arrived with more than $170,000 in U.S. currency), the FBI listened.

* * *

Haupt never did show his true colors. By the time Dasch surrendered to the FBI, Haupt’s group had landed and dispersed. On the submarine, Haupt had persuaded Kerling to allow him to return to Chicago. But Haupt was worried about shocking his parents, so when he did get back to Chicago on Friday, June 19th, he went first to the home of his aunt and uncle, Lucille and Walter Froehling, at 3643 North Whipple Street. The Froehlings thought their nephew looked different—he was wearing a light brown gabardine suit, white and brown two-tone shoes, and a brown felt hat. He had a short beard and appeared tanner than usual. When his mother rushed in, she asked where he had been. He was vague.

“Aren’t you glad to see me?” Herbert said. “I’m back.”

Erna asked Herbert how he had got back, and he said, “Well, I’m back.”

Over dinner, Herbert told his parents and the Froehlings that he had returned to America on a German submarine. At first they didn’t believe him, but he gave details about the relatives he had seen in Stettin. How much he told of his mission is unclear—and it became an issue when his parents and others were charged with treason. What is certain, though, is that he left a zipper bag filled with $15,000 at the Froehlings’ for safekeeping. It was money from Germany to support the sabotage work. He took another envelope containing $3,600 to his parents’ third-floor apartment at 2234 North Fremont Street. The money was later used as evidence at the treason hearings.

The next night, Haupt visited Wolfgang Wergin’s parents, Kate and Otto Wergin, at their South Side home. At first, he told them he had left Wolfgang in Mexico, but later blurted out most of the story. Haupt told the Wergins that if something happened to him, their son would be picked up by the Gestapo. At one point, Otto Wergin guessed that Haupt was in German intelligence. Haupt did not deny it. “If you need me,” said Otto, “I am willing to go along. Just let me know. I am not dumb; I know how to help you out.” That statement was used against Wergin at his trial.

By Sunday, Haupt’s colleague Hermann Neubauer had arrived in Chicago as planned, and he called Haupt at the Froehlings’ house. The two met at the Chicago Theater and discussed their progress while watching the movie The Invaders. “[Afterwards] we took a walk through the park at the lake shore and we discussed how nervous it was just being here, and Neubauer said to me he could never go through with it,” Haupt said at his trial.

Haupt’s mother had told him that the FBI had stopped by in December asking about his whereabouts, so on Monday Herbert went to the draft board to register and then took his newly issued draft card to the FBI’s Chicago office. Haupt thought the meeting went well—he said he had spent the year prospecting for gold in Mexico. But by then the FBI had been alerted by Dasch, and agents started tailing Haupt when he left the office, hoping he would lead them to other German agents.

On Tuesday, Haupt met with his girlfriend, Gerda (who had either suffered a miscarriage or put their baby up for adoption). Haupt talked to her for more than two hours, but never explained why he had not contacted her. He asked her if she wanted to get married the next week and gave her $10 to get the blood test. Gerda later said that Haupt seemed nervous and evasive. “When I accepted [his proposal], he told me he wanted to right the ‘wrong he had done his country,’ but I didn’t understand the meaning of ‘wrong to his country’ until I heard of his arrest,” she later told reporters.

On Wednesday, Haupt met again with Neubauer and also met with a friend— a Nazi sympathizer named Bill Wernecke—who advised Haupt how to falsify medical exams to get a draft deferment (Haupt’s motives are unclear, though it is likely he didn’t want to fight against Germany, even if—as he later claimed—he didn’t want to commit sabotage for her). That night, Haupt’s father bought him a black 1941 Pontiac from a dealership at Diversey and Sheffield Avenues.

Haupt had arranged to get his job back at Simpson Optical, and he was supposed to start on Thursday, but he complained to his mother about pains in his chest and back—the start of his plan to beat the draft. On Friday, he visited a doctor for tests and spent much of the day driving around the city seeing his friends. That night, the FBI followed Haupt to the Blue Danube Tavern and to the Tip Top Tap at the Allerton Hotel.

The FBI finally decided to pick him up a few minutes after he left home on Saturday morning. He was taken to the FBI office downtown, stripped, searched, and given other clothes. Haupt signed forms authorizing the FBI to search his home and keep him in custody and a form waiving his right to be arraigned. During the next several days, as he was being transported to the FBI offices in New York, he signed two long statements that detailed his involvement in the sabotage mission. Haupt and Neubauer—who was apprehended at a Chicago hotel—were the last of the eight saboteurs to be arrested.

That night, J. Edgar Hoover told reporters of the plot and of the arrests, making it sound as if the FBI had cracked the conspiracy, not that the sabotage leader had turned the group in. Hoover’s dissembling was only partly to boost the image of the FBI—the government also wanted the Germans to think the United States had a mole in the Abwehr.

The arrests came at a particularly welcome moment for the United States. The Allies had made little impact slowing the Axis during the six months since Pearl Harbor. Days before Hoover’s announcement, German troops under Field Marshal Erwin Rommel had captured Tobruk, in Libya. It seemed as if the Axis was advancing on every continent.

On June 29, 1942, the Chicago Sun wrote that the accused saboteurs might escape execution if tried in a regular court. “Informed sources doubted they would walk ‘the last mile’ because they were nabbed before they did any damage,” the paper said. The U.S. government had the same doubts. Francis C. Biddle was the Attorney General at the time. In his 1962 memoir, In Brief Authority, Biddle wrote, “Probably an indictment for attempted sabotage would not have been sustained in a civil court on the ground that the preparations and landings were not close enough to the planned act of sabotage to constitute attempt. If a man buys a pistol, intending murder, that is not an attempt at murder.”

President Roosevelt and his team took fast action. On June 30th, Biddle declared that the military had jurisdiction. In his memoir, he detailed the reasons for preferring a military trial over the court system: The military trial would be quicker, it could be held in secret, and it used more lenient rules for admitting evidence.

Two days later, on July 2nd, Roosevelt announced that the suspects would be tried by a military commission in Washington, D.C., and signed an executive order. He placed himself in charge of reviewing the verdict and stated that a vote of only two-thirds of the judges was needed to convict or sentence the suspects.

Washington attorney Lloyd Cutler, who helped prosecute the accused saboteurs, says he does not recall anyone protesting the tribunal. “We all thought of this as the first great U.S. victory after Pearl Harbor, and we needed it,” he says.

In an editorial, the Chicago Daily News wrote, “This is no time to be squeamish. The case is one for martial law and military tribunals, no matter who made the arrests. The people expect stern action, fully publicized by radio to the entire world. Americans are not softies, and they certainly do not want to invite more spies here by ill-timed leniency.”

The trial opened on July 6th in a blackout-curtained conference room in the Department of Justice building in Washington, D.C. Seven military generals, none of them trained in the law, served as judges. They sat at one end of the room on a raised platform. To their right were the eight defendants, arranged alphabetically, each separated from the others by army guards. Attorney General Biddle headed the prosecution. Colonel Kenneth C. Royall led the defense for the accused saboteurs, and observers said he did a spirited job. Still, he notified his boss, the Secretary of War, before taking major steps. Years later, Dasch wrote, “I don’t like to refer to the procedure that we had been put through as a trial. It was not a fair trial; it was not my idea of an honest American trial.”

The proceedings were carried out under strict military guard. Armored vans, accompanied by a phalanx of soldiers, drove the defendants to court. Fifty soldiers stood guard outside. Absolute secrecy was the order. “Now and then—very rarely—the reporters put two and two together,” wrote Biddle, “and did some clever guessing: Haupt, when arraigned, had a bandage on his left wrist and was handcuffed by the right wrist to a deputy marshal. He was reported to have torn his wrist artery with his teeth in a vain attempt at suicide.” (Today, it is not known if the report was true.)

Haupt pleaded not guilty to all charges. He told the judges that he had never intended to follow through on the sabotage plot; he was going to turn in the saboteurs when they gathered as planned in Chicago on July 6th. Haupt testified for hours, over a period of several days, repeating essentially the same story he had told the FBI. At one point, he was asked by Major General Frank R. McCoy, president of the tribunal, what he believed would happen if he told Kappe he would not come to America.

“In the position that I was, not being a German citizen and having trouble with German officials—well, I can’t definitely state what would happen to me. I would have probably went to a concentration camp or—that is about all they could have done to me.”

Three people were called to testify in Haupt’s defense. His mother, his girlfriend Gerda, and the mother of his best friend talked briefly about his week in Chicago following his return. Gerda said she agreed to take the blood test, but was not convinced she would marry him. “I wanted to bide for time,” she said.

On July 28th, the proceedings were halted after defense attorneys persuaded the Supreme Court to consider the constitutionality of the military court. “We have to win in the Supreme Court,” Biddle had warned FDR, “or there will be a hell of a mess.” For nine hours over two days, attorneys and justices argued over the defense claim that the trial was illegal. The defense raised a number of issues, among them that the military commission denied the accused saboteurs their constitutional rights and that the President had improperly placed himself in a position to review the case. Defense attorneys also argued that, as a U.S. citizen, Haupt, at least, was entitled to be tried in civil court.

On July 31st, the court issued a brief, unanimous order allowing the trial to continue. On August 3rd, the military commission found all eight saboteurs guilty of war crimes, a collection of offenses that ranged from spying to appearing behind the lines in civilian dress. On August 8th, six of the eight convicted saboteurs were electrocuted in the District of Columbia jail. It took a little more than an hour to execute all six men. Haupt was the first to die. Roosevelt commuted the death sentences of Dasch and Burger, who had cooperated with the government, to long prison terms—Dasch got 30 years; Burger, life—partly to hide their cooperation.

Three months after hearing the arguments, the Supreme Court issued a written opinion explaining the reasoning behind the earlier order. Basically, the court said that the Constitution gave the President, as commander in chief, the right to appoint a military commission to try the accused saboteurs, and nothing in the Constitution or the law gave them the right to a civil trial, with all the safeguards usually accorded defendants.

“It is the most Delphic, inscrutable decision you have ever seen,” Lloyd Cutler says. “But I don’t think there is any doubt that it was the proper decision. These guys were spies, caught with explosives, disappearing ink, out of uniform, behind the lines.”

Some scholars disagree. “The grounds given by the court for its decision are questionable,” says David J. Danelski, an emeritus Stanford University professor who wrote about the saboteur case in a 1996 article in the Journal of Supreme Court History. Danelski says that Chief Justice Harlan Fiske Stone and Justices William O. Douglas and Felix Frankfurter all voted in favor of the tribunal, but later came to think that the law did not support their decision (Frankfurter called it “not a happy precedent”). “It was bad law, and they knew it,” Danelski says. “That’s what is so frightening about the decision—it is being used as authority today.”

* * *

Within hours of Herbert Haupt’s arrest, the FBI started building a case of treason against his parents, the Froehlings, and the Wergins. The three husbands were detained and jailed. Soon all six defendants had signed a series of “voluntary statements” that described how much Herbert had revealed during his eight days at home.

The six were charged with treason, the only crime defined in the Constitution: “levying war against [the United States], or in adhering to their enemies, giving them aid and comfort.” For the government, treason is a hard case to make since the Constitution requires it be proven by “a confession in open court” or “the testimony of two witnesses to the same overt act.”

The trial began on October 26, 1942, in the old domed Federal Courthouse in the Loop. Presiding judge William Campbell was one of the youngest district court judges in the nation and a hard-line former U.S. attorney who ruled against just about every motion made by the defense. The FBI spared no expense in bringing people to Chicago—from hotel clerks in Florida to the Wergins’ acquaintances in Connecticut—to reconstruct Herbert Haupt’s movements in America and the couples’ role in helping him. The star witness was saboteur Ernest Peter Burger, who established Haupt’s place in the failed mission. (Dasch says he refused to testify for the prosecution because he was sympathetic to Haupt’s parents. “Haupt had completely violated orders by going home to his family in Chicago,” Dasch wrote.)

The key to the government’s case against the six defendants was the series of statements, which became more detailed as the defendants admitted more knowledge about Herbert and his mission. Erna Haupt, for instance, said in her two-page June 28th statement that Herbert had told them only that he had been to Mexico. On June 30th, she produced a four-page statement denying that she had overheard Herbert talking about Japan and Germany. On July 1st, she signed a five-page statement in which she admitted that Herbert had told her he had been in Germany and returned on a submarine. She wrote, “I do not know why I was afraid to tell the truth, except perhaps that I was confused and so shocked by it all that I did not know what I was doing.” Finally, on July 3rd, she signed a 13-page statement in which she detailed her conversations with Herbert about his trip to Germany, but still asserted her innocence. “I also wish to state that I did not actually realize the purpose of Herbert’s return to this country and that even if I had realized it I would not have thought him capable of going through with it. Furthermore, after he had visited the FBI office and had been released without further question I thought everything must be all right.”

Defense attorneys tried hard to get these statements suppressed, arguing that they had been given under duress and were untrue. In a hearing, Walter Froehling testified that the incriminating statements had been signed after days of interviews. On one occasion, Froehling said, “I read the statement but I was so nervous and homesick that I didn’t know what I read.” At the time, Froehling testified, he had not slept for three nights. He admitted that the signature was his, but he told the court he did not remember signing the document. The government also called witnesses to testify about the defendants’ pro-German, anti-Semitic attitudes. Mary Fishman, who had employed the Haupts in the thirties and early forties, told the court, “They said that Hitler was a godsend to the people over there.” Another woman testified that Hans Haupt had told her that his American citizenship was meaningless to him.

The defense called no witnesses. Instead, defense attorneys argued that the government had not proved treason. They told the jury that the Haupts and Froehlings had acted out of love and that the Wergins simply wanted a link to their son.

On November 14th, after less than six hours of deliberation, the jury found all six defendants guilty of treason. Judge Campbell sentenced Hans Haupt, Walter Froehling, and Otto Wergin to death in the electric chair. Erna Haupt, Lucille Froehling, and Kate Wergin were sentenced to 25 years in prison and fined $10,000. The stiff sentences made Campbell something of a national hero. Newsweek wrote: “Seldom has a judge so young given a more complete and eloquent summary of a case in passing sentence than that delivered by Federal Judge William J. Campbell.” The judge received dozens of letters and telegrams, almost all congratulating him.

But the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals did not agree. On June 29, 1943, the court unanimously reversed Campbell’s decision and remanded the case for a new trial. The appellate panel criticized Campbell for admitting the defendants’ statements into evidence, for trying all six at once, and for giving confusing instructions to the jury.

Without the statements, the treason case was much more difficult to prove. Meanwhile, all six defendants remained in custody. In 1944, the government made deals with five of them. Lucille Froehling and Kate Wergin were unconditionally released. Walter Froehling and Otto Wergin pleaded guilty to “misprision of treason” and got five-year terms, part of which had already been served. Erna Haupt was interned and denaturalized. She was deported to Germany after the war.

But government prosecutors retried Hans Haupt, probably because they had the strongest case against him. He had bought the car for his son—an overt act in furtherance of the sabotage mission, the government said—and he had made the most damning pro-German remarks. The second trial featured many of the same witnesses, including Burger. This time, the jury deliberated for 28 hours before convicting Haupt of treason.

At the sentencing on June 14, 1944, district court judge John Peter Barnes called Hans a “fanatical Nazi”; at one point, the judge said his instinct was to sentence Haupt to death. But something at the trial had apparently touched the jury. Though they had convicted Haupt, the jurors sent Barnes an unusual note, asking him to deal mercifully with the defendant. “In deference to the request of these men and women, whose judgment may be better than mine, the sentence will be life imprisonment . . . ,” Judge Barnes announced.

* * *

Today, the fates of many of the people involved in the saboteur cases are hard to determine. After being imprisoned in the federal facility at Danbury, Connecticut, Hans Haupt was deported to Germany after the war. The Wergins returned to their lives in Chicago. Otto Wergin managed the bar at a North Side club before they retired and moved to California.

The surviving saboteurs, George Dasch and Ernest Peter Burger, were imprisoned until 1948 and then deported to Germany. Dasch, who had expected to be honored by the U.S. government, later found himself hounded by Germans as a traitor. He died in 1991. Burger has disappeared into obscurity.

Wolfgang Wergin, Haupt’s companion on the trip to Mexico, had his own disastrous experience in Germany. Though he was a U.S. citizen and spoke only a few words of German, he was drafted into the German army. Wergin served in the infantry on the Russian front, rising to a rank similar to that of lance corporal. By his second year, Wergin was a hardened veteran and had won several medals, including the Iron Cross. In late 1944, while being treated for back wounds at a hospital, he managed to switch outfits and got sent to France. “From the moment I got to the front lines there, my intention was to get over to the other side, somehow, without getting shot,” he says.

Eventually, Wergin got a chance. When he saw a wounded GI in a ditch between the two lines of fire, he dove into the ditch and covered the soldier. Wergin stayed there until GIs overran the area, and he was taken prisoner. In the spring of 1945, while still in camp, Wergin found a copy of Coronet magazine and read about the fate of Haupt and of his own parents. The article said they had been sentenced to death. Only later did he learn, through a family friend, that his parents were alive.

After the war, Wergin tried to get back to the United States, but was denied a visa because of his service in the German army. He married, had two daughters, moved to Colombia, and eventually returned to the United States in 1956. His parents went to the airport in Chicago to greet him. He was home, 15 years late. Wergin never discussed the case with his parents. “I didn’t know how to bring it up,” he said. Otto Wergin lived to age 75, Kate Wergin to 84.

Wolfgang Wergin became a U.S. citizen again in 1962. He worked as a professional photographer for nearly 40 years in Las Vegas. Now he is trying to understand Herbert Haupt and the grand adventure that changed everything. He thinks sometimes about visiting Haupt’s grave. It is in Washington, D.C., marked only by a number—278—in a potter’s field at the former Home for the Aged and Infirm.

Shortly after Herbert Haupt was electrocuted, his mother asked officials in Washington if his remains could be cremated and given to her. The request, sent to President Roosevelt, was denied.

The record of Haupt’s trial was kept secret for about 15 years after World War II. The transcript, now at the National Archives in College Park, Maryland, is on thin stationery as fragile as the issues that decided the case.