You have sworn off campaigning and taken a new job: director of the Institute of Politics at the University of Chicago. What is the institute, and how will it work?

It will be a center to encourage young people to engage in policy and politics, to see public life as a noble pursuit. It will be not-for-credit and nonpartisan, similar to the Institute of Politics at Harvard [started in the 1960s by the Kennedy family]. There will be three main components: First, we will host speeches and debates on matters of global, national, and local importance so that the institute will be seen as a destination for policymakers and people of influence. Second, we will bring in practitioners—a White House speechwriter, say, or a pollster, or a campaign strategist. Third, we will help kids get involved in real-life public policy work. That could range from government to journalism.

Whose idea was the institute—the university’s or yours?

I took the idea to the University of Chicago and to Northwestern University [where he was an adjunct professor from 1998 to 2005]. I decided I could have more impact at the U. of C., using the institute to bridge the high-minded academic pursuits with community engagement. Northwestern has other outreach programs.

Related:

Axelrod’s Last Campaign »

Our story from September 2011

You’re a U. of C. alum (BA, 1976). Did fondness for your Hyde Park years have anything to do with the decision?

I actually felt a kind of frustration in my days at the U. of C. It was very inward-looking and intense, and I was more interested in the world outside. I had come to Chicago [from New York City, where he grew up] because the U. of C. was such a great school and because the city had this tremendously rich political life. I wasn’t just interested in books; I wanted to participate in what was going on outside. When we were talking about the [Institute of Politics], I mentioned that sense of frustration to Bob Zimmer [university president since 2006], and he said, “That’s why we need you to come here.”

Some people might assume the institute will favor ideas in sync with liberal or Democratic Party values. How will you be nonpartisan?

We will have speakers and participants who work for Republicans as well as Democrats. Take a look at our board of advisers [see below].

During the campaign, Chicago was often painted by your opponent as old-school, machine run, and corrupt. Are you concerned that basing your center here will pose image problems?

The city has moved far beyond that. [Mayor] Rahm [Emanuel] is doing things that are earning him praise from around the country, even around the world. It’s worth noting that the people who cast Chicago in those negative images—they lost the election.

You claim that the 2012 campaign was your last. Are you really done?

I’m done. Having said that, the president is a friend of mine, and when he wants to talk, I’m going to take the call.

Do you call the president? Or does he call you?

It goes both ways. We’ll usually be e-mailing back and forth, and one of us will say, “Hey, let’s just get on the phone.” Sometimes we’ll talk a couple of times a week. Sometimes we’ll go two

weeks without talking.

Do you still give him advice?

What I tell him—and he doesn’t need any telling—is be true to the central themes that brought you into public life. That’s pushing back against some of the economic forces that have made it difficult for the middle class.

But a lot of the time, we’re not even talking about politics. We’re talking about family things or something else. You know, he was my friend before he was the president.

What’s the status of Axelrod Strategies, your River North–based consulting group?

It’s on hold. For many years, my work and career have meant a lot of sacrifice by my family [his wife, Susan, and grown children, Lauren, Michael, and Ethan]. I’d like to spend more time with them.

In December, you shaved your mustache as part of a fundraiser to raise $1 million for research for epilepsy, which afflicts your daughter, Lauren. Will you be involved in raising money or awareness for any other cause?

I’d like to work toward a greater understanding of mental health issues. My father committed suicide when I was a student at the University of Chicago. I didn’t really talk about it for 30 years. And the reason, I think, is the same reason that he didn’t ask for help: the stigma of depression. As a society, we have to come to view mental health issues the same way we view other health issues, like cancer.

What did Obama’s reelection feel like?

You know, I had thought there’s no way it could be better than the first election. But it was better because [the campaign] was harder this time.

Did you ever, even for a moment, think that President Obama would not win?

I never had a doubt. We had good data. That doesn’t mean I didn’t get nervous at times. But I never had a doubt.

* * *

Party People

Some of the prominent players Axelrod tapped from his past life for the Institute of Politics board

THE MEDIA

Conservative commentator William Kristol, Univision news president Isaac Lee

THE ELECTED

San Antonio mayor Julian Castro (keynote speaker at the Democratic National Convention), Massachusetts governor Deval Patrick

THE INSIDERS

Republican strategist Mike Murphy, Obama 2012 deputy campaign manager Stephanie Cutter

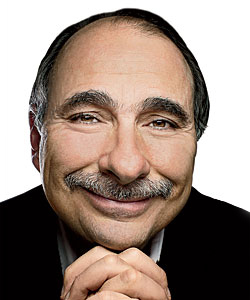

Photography: (Axelrod) Chris Strong; (Lee) Craig Ruttle/AP; (Castro) Pat Sullivan/AP; (Patrick) Steven Senne/AP; (Murphy) J. Scott Applewhite/AP; (Cutter) Charles Rex Arbogast/AP