"I don't really care about the guy in the nine-to-nine 'I'-banking job who says I'm not doing enough," says Chambers, bouncing the question right back: "What do you add to society?"

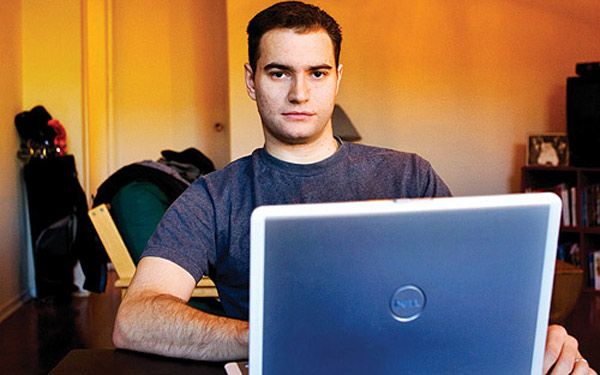

On Thursday morning, October 12th, one day before President Bush signed a law essentially making online gambling illegal, Tom Chambers sat at his computer in the cramped back bedroom of his unkempt apartment in Lincoln Park, doing his job. He played nine simultaneous games of Six-Handed No Limit Hold 'Em-folding on this hand, betting on that one, bluffing here, calling there-meanwhile talking a stream of strategy. A befuddled writer nodded in feigned comprehension and turned on the tape recorder:

"A pretty standard situation in a heads-up raised pot is that neither player really has much of a hand, including the person who raised. Like the hand where I just had jack, nine of diamonds. I raise; the guy calls; the flop comes king, ten something. I've got a gut-shot straight draw, and so I've got some chance of making the best hand. Mostly I'm just bluffing here, but there's a little bit of a semibluff in the bluff. It's not just a straight bluff because I can catch a queen to make a straight. . . ."

And on like that, without pause. For two hours straight.

Tom Chambers-26, Harvard '02, former private school teacher and actuary, newlywed-is the round electronic icon you're playing and probably losing to on the computer in Sunday morning poker tournaments and Thursday night games of Texas Hold 'Em, Pot Limit Omaha, Stud Hi/Lo, and Razz. He's a professional poker player, and he makes his living working percentages and outthinking casual online gamblers while playing 45 to 50 hours a week. Competing in up to 12 games at a time, he ends up playing roughly 100,000 hands a month.

Though he has been a winning amateur player for a couple of years, Chambers started playing full-time this past summer only after quitting his job at an actuarial firm. He plays for midlevel stakes-a large pot in a typical game is a few hundred dollars-winning at a rate that makes an annual income in the low six figures an ambitious but reachable goal. Through practice and discipline, he hopes to be good enough within a year to graduate from his current role as a "grinder" to higher-stakes games that could get him into the multiple six figures. "I'm still developing my skills," he says.

Photograph: Peter Wynn Thompson

When you watch Chambers play and listen to him talk about his poker strategy and his philosophy of gambling-he is as thoughtful as he is sharp-you want to bet the pot on his success in this fast-growing field (the Associated Press reported in October that the global industry would pull in $15 billion in 2006, up from $12 billion in 2005). But his professional career has come into jeopardy with the passage of the Unlawful Internet Gambling Enforcement Act, signed into law October 13th. The law prohibits banks from allowing online gamblers to use credit cards, checks, and electronic fund transfers to settle their bets. Though there is much ambiguity as to whether Internet gambling was illegal all along-courts disagree on whether it violates a 1961 law prohibiting betting over the phone-most large financial institutions have little to gain by challenging the latest crackdown. Operators of the poker sites that remain open to U.S. players hope to find easy, legal ways for casual players to handle money, but the online gambling business worries that, when people can't use their Visa cards, many will go back to solitaire.

The chief proponents of the new law-Republican congressmen Jim Leach of Iowa and Bob Goodlatte of Virginia-contended that burgeoning Internet gambling was ruining lives ("Click your mouse, lose your house"). Leach argued that online gambling in effect brought the casino into "the home, office, and college dorm. Children may play without verification, and betting with a credit card can undercut a player's perception of the value of cash, which too easily leads to bankruptcy and crime."

After the measure passed the House, Senate majority leader Bill Frist attached it to an unrelated port security bill, and the proposal sailed through.

Online gamblers naturally decry the change and offer differing predictions as to how and whether the act will be enforced. Internet gambler Charles Murray of the conservative American Enterprise Institute argued in The New York Times that gambling sites outside the United States would continue to handle American customers because "it is absurdly easy to devise ways of transferring money from American bank accounts to institutions abroad and thence to gambling sites."

So far, the act hasn't cramped Chambers's style. His preferred site, Costa Rica–based PokerStars.com, continues to welcome Americans. And Chambers is confident that new e-commerce companies will step up to process gamblers' payments. Still, he admits, "this is a PR hit."

For pro players like Chambers, public relations is important, because the public is important. The suggestion of illegality might drive away casual players-the overwhelming majority of the 23 million Americans said to gamble online. And pros need lots of amateurs and the "dead money" (as their easily poached dollars are called) to make their living.

Chambers acknowledges that the law passed quietly because nobody cries for poker players, amateur or professional, except the players themselves. While Chambers believes he and other pros should be allowed to make a living at this, "it's almost more offensive to me," he says, "that Joe Businessman can't come home and do this after work to relax."

At first blush, Chambers doesn't own the résumé you would expect of a professional poker player. He's the son of two public school teachers from Royal Oak, Michigan, and a graduate in intellectual history from Harvard University. He wrote his thesis on Nietzsche and Wittgenstein and their treatment of language and metaphysics, but he credits his late father, a math teacher, with giving him a head for cards (though no direct training; Chambers played poker for the first time, and only a couple of times, in college). After graduating, he taught calculus, algebra, and world history and coached basketball for three years at a private school in St. Louis, where he met his future wife, Torey Cummings. Also in St. Louis-aboard the casino boats on the Mississippi-Chambers began to fall for another love. Eventually, he and Cummings both ended up in Chicago, she to become an attorney at Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom, and he to take the actuarial job. He got more successful in online poker games and tournaments on nights and weekends, until finally he quit the actuarial job, which bored him, to play the game that never did.

Though his wife was happy he had quit an uninspiring job, his new calling made her nervous. "At first I was like, ‘Oh, my God, we lost a thousand dollars,'" Cummings says. "But you forget: he won $10,000 last week. You have to look at it long-term." Meantime, she has also learned how to play poker and occasionally plays online and at casinos, though for lesser stakes than does her husband.

Chambers is loaded for accusations that he ought to be doing something more meaningful with his life. "I don't like it that people are identified with their job," he says, adding that a few months earlier when people asked what he did, he told them he was an actuary and their eyes glazed over. "Now I'm a poker player and everyone wants to hear about it." He adds that the earnings and the flexibility of his work potentially allow him to do anything he wants. Besides, online poker players aren't the only kinds of professionals who earn their living by winning a zero-sum game (where total gains are balanced by total losses). "I don't really care about the guy in the nine-to-nine ‘I'-banking job who says I'm not doing enough," he says, bouncing the question right back: "What do you add to society?"

Chambers says his main defense against serious loss is a detailed business plan that mandates what he calls an "ultraconservative," mutual-fund-like spread of his $50,000 bankroll across five types of games with varying levels of risk. His days and weeks are scheduled carefully to accommodate the mental and emotional rigors of poker. On a typical workday, Chambers plays a multigame "session" from 10 a.m. to noon. Then he eats lunch and works out-he plays basketball-and plays another two-hour session sometime between 2 and 6 p.m. After dinner, he'll likely play for two or three hours. He doesn't take Sundays off-there's a lot of dead money available in Sunday tournaments-but he will take a day off here and there, and he always takes a half-day after a particularly good or bad day at the computer (which he defines, respectively, as winning $2,000 or losing $1,000). Neither euphoria nor despair, he says, leads to smart poker.

Hanging around with Chambers feels less like being with a cardsharp than being with a chess master. He's got a bookcase full of poker books, to which he devotes hours every week. Though he doubts that he quite possesses the "almost mystical" qualities to become a truly great player, he clings to the hope of achieving greatness through playing countless hands and figuring out betting patterns. "What separates the greatest players from the merely great or good is hand-reading ability-the ability to understand, from knowledge compiled all your life, based on the way a person is acting, to know what they have, why they're playing their hand the way they are."

Online the clues are reduced, since he gets no visual or verbal signals from his opponents. (He occasionally plays live games at casinos "for variety" and finds those games "softer"-easier to win-than online games; his earnings are limited, though, because he can't play more than one at a time.) Already, Chambers can as much as see through the cards of the typical beer-drinking Saturday night poker player and predict his every next move. At the highest levels, he says, the players can understand almost every poker hand that way.

Chambers is less adept at predicting his own future. Ask him what he'll do if the Unlawful Internet Gambling Enforcement Act shuts down the opportunity to make a living from his back bedroom, and he runs through assorted possibilities. He might coach high-school basketball, go back to school, take up live poker full-time. He suspects he may end up an academic. "But as long as online poker is viable, it's my main focus," he says.

In other words, he's going to play the hand he's dealt.