Year after year, Lucy Page Gaston sat through Chicago City Council meetings and legislative sessions in Springfield. Even as politicians exhaled clouds of tobacco smoke, the prim lady in a somber black dress urged them to pass laws restricting cigarettes. Gaston carried a handbag stuffed with pamphlets, along with a supply of graham crackers and her trusty antismoking remedy, gentian root. At times, when Illinois legislators dragged their discussions past midnight, Gaston was the only citizen sitting in the gallery, peering at the proceedings through her rimless round spectacles.

Her legislative triumph came in 1907, when the General Assembly passed a law banning cigarettes. No one would be allowed to make, sell, or give them away in Illinois. But Gaston’s success quickly turned sour: Two days before the cigarette ban was slated to take effect, a judge snuffed it out.

Almost precisely a century later, the Illinois General Assembly has approved a bill that prohibits smoking in restaurants, bars, workplaces, and all public buildings. The law takes effect January 1st, making Illinois the 19th state to adopt such restrictions. Eight decades after Gaston’s death, her campaign to curtail smoking is winning some belated victories.

* * *

In the early years of the 20th century, Lucy Page Gaston was the most famous anticigarette crusader in the country, a cantankerous zealot often compared to Carry Nation, the hatchet-wielding enemy of saloons. Gaston grabbed children on Chicago’s streets when she saw them smoking, hauling them to the nearest cop. She harangued everyone from Britain’s Queen Mary to prostitutes at the Everleigh Club about the danger of smoking those little white sticks she liked to call “coffin nails.”

“Lucy Page Gaston was a complicated combination of moral concerns about smoking, but also very serious concerns about the health and medical implications of smoking,” says Allan Brandt, a professor of the history of medicine at Harvard Medical School, who wrote about Gaston in the recently published book The Cigarette Century. This mix of morality and medicine was typical of that era, Brandt says.

Born in Ohio in 1860 and raised in Lacon, Illinois (upriver from Peoria), Gaston came from a family with a history of fighting for abolition and prohibition. A schoolteacher by the age of 16, Gaston was appalled when she saw boys smoking. “The back rows of her classrooms were filled with surly, shuffling boys who failed their examinations, who loitered on street corners after school, caps on the sides of their heads, hands fumbling in pockets,” Frances Warfield wrote in a 1930 magazine article about Gaston. “Miss Gaston knew; there were cigarettes in those pockets.” While attending the Illinois State Normal School (now Illinois State University), Gaston led raids on saloons, gambling dens, and tobacco shops.

She was known as a “new woman.” Single all her life, she advised women to consider pursuing careers instead of marrying. “The lives of society girls are frittered away in uselessness,” she said. Tall, angular, and bony, with dark hair and spectacles, she often wore the white ribbon, a symbol of temperance, sometimes adding a miniature hatchet for emphasis. She struck observers as brainy and confident. Neighbors knew Gaston as something of a scold. She once yelled across the street at a man for slouching as he walked. “You straighten up!” she said.

Around 1893, Gaston moved with her parents and brother, Edward Page Gaston, another temperance activist, to Harvey. The evangelist Dwight Moody was extolling the virtues of that “Magic City,” which had sprung up among Chicago’s south suburbs in 1891. Harvey, he said, was “an earthly paradise which had never been defiled by painted windows and the music of gurgling bottles.” All property deeds in Harvey included a pledge against serving alcohol, gambling, or manufacturing gunpowder on the premises. A promotional book for Harvey promised “absolute protection from the evils which spring from drinking places, gambling hells and low resorts.”

Gaston became managing editor of the Harvey Citizen, and when Harvey officials issued a license for a tavern in 1895, Gaston led a protest by temperance advocates. She was arrested twice for criminal libel, though the charges were quickly dismissed. “She wields a trenchant pen,” the Chicago Tribune noted. Despite Gaston’s efforts, liquor eventually flowed in Harvey. Speaking at a national meeting of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, Gaston described her struggle against “the ravening wolves of the liquor traffic” in apocalyptic terms. “I know what it is to have a hand-to-hand conflict with the powers of darkness,” she said.

|

|

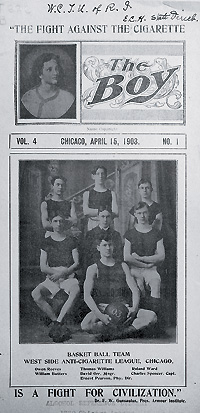

Gaston was already turning her wrath upon the cigarette, which had been gaining popularity since the invention of an efficient rolling machine in 1881. (In the early years of the last century, cigarettes were still seen as something of an oddity compared with cigars, pipes, and chewing tobacco.) Gaston founded the Anti-Cigarette League at the end of 1899, working out of the Woman’s Temple, a grand castle of an office building, which also housed the WCTU, at the southeast corner of LaSalle and Monroe streets. Within two years, Gaston claimed to have signed up 300,000 members. She published a magazine called The Boy, aimed at persuading boys that cigarettes were a danger to their health, minds, and morals. “Boys who use cigarettes are like worm apples,” Gaston said. “They drop before their time.”

It was already obvious to many that cigarette smoking harmed the body, but it would be decades before those concerns were verified in scientific studies. “Smoking was often associated by physicians with respiratory problems and problems of the heart,” Brandt says. “The problem was, How do you go from those kinds of clinical observations to systematic understandings of risks and causes?”

The vagueness of those early worries about cigarettes led to some dubious claims. Gaston’s league handed out a pamphlet with a story from the Evanston Index recounting how a doctor demonstrated the ill effects of cigarettes to a young smoker: “The cigarette fiend bared his pale arm, and the [doctor] laid the lean, black leech upon it. The leech fell to work busily, its body began to swell. Then, all of a sudden, a kind of shudder convulsed it, and it fell to the floor dead. ‘That is what your blood did to that leech,’ said the physician. He took up the little corpse between his finger and thumb. ‘Look at it,’ he said. ‘Quite dead, you see. You poisoned it.'”

Brandt says Gaston faced a fundamental problem: Tobacco companies guarded their recipes for cigarettes as proprietary secrets. Even today, the government does not regulate cigarettes as a drug, and so, much about them remains a mystery. “Gaston was on to something important,” Brandt says. “The cigarette is a very complicated device. And so it would be difficult to know exactly what elements . . . were creating the harms that we now understand cigarettes to produce.”

Gaston and her allies believed cigarettes also damaged a smoker’s mind and moral character. An Anti-Cigarette League pamphlet quoted Thomas Edison as saying, “I really believe that it often makes boys insane.” These worries provided fodder for the eugenics movement. The “race” seemed to be degenerating, some people said, and cigarettes were one cause of this decline. Gaston was present in January 1914 when followers of this theory gathered at cereal magnate John Harvey Kellogg’s Battle Creek Sanitarium for the first National Conference on Race Betterment. One speaker, Melvil Dewey, of Dewey decimal system fame, called cigarette smoking “a thing that is pulling down the race.” Without addressing racial theories, Gaston gave a straightforward plea to rouse children against cigarette use. “We are not giving the boys and girls today a chance to have their blood stirred by any great splendid, heroic moral reform,” she said.

Gaston attracted children to her cause by hosting dances, sponsoring basketball teams, and awarding prizes for essay writing. In 1902, she presided over a ritual destruction of tobacco inside the Woman’s Temple. Boys marched and sang, “Hurrah! Hurrah! The cigarette, you know. Hurrah! Hurrah! The cigarette must go!” Playing the devil, a Hyde Park boy in red tights, horns, and hooves stirred up a pot of cigarettes with a pitchfork. The cigarettes were set ablaze, filling the room with smoke. Children sneezed and rubbed their eyes. Gaston explained that she’d wanted “to make things smell bad.”

One Chicago boy who signed the Anti-Cigarette League pledge was Cyrus LeRoy Baldridge, later a well-known artist. In his memoirs, Baldridge recalled enlisting “under the spell of a Sabbath school lecture by Miss Lucy Page Gaston. Though smoking had never tempted me, its immorality and dangers had been so vividly described that gladly I had signed the pledge to refrain from cigarettes until twenty-one.” (Actually, the pledge included no expiration date.)

In 1900, Gaston persuaded some Chicago companies to bar cigarette smoking by employees. Montgomery Ward & Co. was one of the first to adopt the policy—which applied both during and outside of work hours. Business owners believed that smoking harmed young people’s brains. “The new generation is growing up utterly incompetent,” one said. Employers checked the hands of job applicants, saying, “Hold up your mitts!” and looking for cigarette stains.

Once, when Gaston nabbed a messenger boy and demanded his arrest for breaking the state’s law against smoking by minors, a crowd surrounded her. “I thought I was going to be mobbed,” she said. “A man came up to me, shook his fist in my face, and dared me to have the boy arrested.” The Chicago Police deputized Gaston for a while as a special officer with the power to arrest underage smokers.

Rather than prosecuting young smokers, Gaston preferred to recruit them as informants. She sent her boys into shops and reported on the merchants who sold cigarettes to minors. When the Anti-Cigarette League used this tactic in Washington, D.C., in 1900, newspapers criticized her for “corrupting the schoolboys by setting them at the meanest and most contemptible industry conceivable—that of the informer and the spy.” Gaston, who preferred to call her boys “detectives,” said, “This is the only way to get evidence.”

Gaston promoted various cures for cigarette addiction, including a fruit diet. After nabbing a 16-year-old boy smoking a cigarette in 1911, she remarked, “If Joe will only eat fruit, he will lose his taste for cigarettes in two or three days.” Gaston claimed that chewing the root of the common flowering gentian plant had a similar effect.

As early as 1900, Gaston recognized that a growing number of girls and women were smoking. And it wasn’t just girls from “the vicious and evil classes,” Gaston said. In fact, she believed lower-class women were taking up the habit after seeing actresses and society ladies smoking. “They adopt it because they think it is smart,” she said. Gaston and other moralists of her era viewed cigarettes as a gateway drug that led to alcoholism, crime, and sexual promiscuity. These concerns were especially apparent in their comments about female smokers.

Gaston led a band of reformers on a “slumming trip” into Chicago’s red-light district in 1907. Minna Everleigh welcomed Gaston into the legendary Everleigh Club and allowed her to interview the prostitutes. “Miss Gaston, you’re a good fellow,” Everleigh said. “You can come down here and bring your clubwomen whenever you want. If you can get one of my girls to leave me or if you can keep any from coming here, I want you to do it. But you’ll never succeed, Miss Gaston, never as long as the girls are young and pretty and fond of fine feathers.” Gaston couldn’t help herself from asking a prostitute if she smoked. As Gaston wrote in a Tribune article about the visit, “The subject of cigarets [sic] always is uppermost in my mind.” The prostitute told Gaston that she had never smoked and that she didn’t drink wine, either. “So much in her favor,” Gaston wrote.

Gaston often made a point of urging public figures to set a good example by avoiding cigarettes. When Theodore Roosevelt was president, Carry Nation saw a picture of him on the wall of Gaston’s office and exclaimed, “Don’t you know he’s a cigarette smoker? Let me tear that picture up.” Refusing to believe it, Gaston wrote to the White House. Roosevelt’s secretary, William Loeb, replied: “The president does not and never has used tobacco in any form.” Later, Gaston wrote to Britain’s Queen Mary after reading an

article about Her Majesty’s fondness for cigarettes after lunch.

Some people thought Gaston’s abrasiveness was counterproductive. When Gaston confronted a group of tobacco company executives in 1904, one of them said: “By advertising the cigarette, Miss Gaston, and by publicly proclaiming its ‘devilish character,’ you have made it attractive and increased its smoking among boys who otherwise would not have thought of experimenting with it.”

|

|

Gaston’s unceasing lobbying finally won over Illinois lawmakers in 1907, when they passed a bill making it illegal to make, sell, or give away cigarettes anywhere in the state, punishable by a fine of up to $100 and 30 days in jail. The law was scheduled to take effect on July 1, 1907, and as the date approached, the Tribune declared: “Buy Your Cigarets Now.” R. M. Berlizheimer, who sold tobacco at the Chicago Stock Exchange building, sued to stop the ban, and Cook County Superior Court judge Axel Chytraus killed it on a technicality. As Chytraus pointed out, the law’s title described it as an act to “regulate” cigarettes. A law that regulates cannot prohibit, Chytraus ruled. Other sections of the law, making it a misdemeanor for children 18 and younger to possess cigarettes, stayed on the books.

Six months later, the Illinois Supreme Court sustained the decision, though chief justice John P. Hand found other faults with the law. He pointed out that the law applied to “any cigarette containing any substance deleterious to health,” including tobacco. The way Hand interpreted that clause, cigarettes made from “pure tobacco” were legal, while cigarettes “impregnated with drugs” were illegal. Berlizheimer planned to sell cigarettes made from “pure tobacco,” so the law did not apply to him, Hand wrote.

The cigarette ban never took effect, though it was not formally repealed until 1967. Fifteen states passed cigarette prohibition laws between 1890 and 1930, but none of the laws lasted. Tobacco companies fought the bills with campaign contributions and, some said, bribes. Gaston kept up the pressure for a law in Springfield, but she never came as close to success as she had in 1907. By 1917, when Gaston spoke to the Chicago City Council, aldermen seemed to regard her anticigarette sentiments as a joke. One remarked, “Why, the mayor and about half the aldermen smoke them.”

As the United States entered World War I, cigarettes came to be seen as an object of comfort for the American doughboys fighting in European trenches. Gaston opposed sending cigarettes to the soldiers, prompting a sharp rebuke from Chicagoan Jessie E. Pershing, sister-in-law of General John Pershing, commander of the American Expeditionary Force in Europe. “If these boys who are offering their lives for the cause of democracy and humanity can find any comfort or solace in smoking a few cigars or cigarets [sic], for heaven’s sake why not let them smoke in peace?” Pershing told the Chicago Tribune in 1918. Some groups that had opposed tobacco use, such as the YMCA, distributed cigarettes to the front. “The war itself was far more significant than advertising or any other factor in promoting cigarettes,” Cassandra Tate wrote in her 1999 book Cigarette Wars. Some physicians even said that cigarettes had a calming effect, easing the “intense nervous strain” that soldiers faced.

Seemingly unaware that her crusade was waning, Gaston sought the Republican nomination for president in 1920, running on a platform of “clean morals, clean vote and fearless law enforcement.” Few took her seriously. Listing Gaston’s reasons for running, the magazine writer Frances Warfield noted: “She looked like Lincoln.” As it turned out, the Republican nominee that year, Warren G. Harding, was a smoker. After Gaston urged him to stop smoking, Harding agreed it was a good idea to “save the youth of America from the tobacco habit,” but he criticized the anticigarette movement’s “hypocrisy” and “deceit.”

In August 1921, the Anti-Cigarette League’s board of directors fired Gaston, saying it wanted to focus on educating children about the dangers of smoking, rather than continue to follow Gaston’s “more drastic” approach of seeking prohibition of cigarettes. “She is a good old soul, but she is too radical,” said the chairman, Frank M. Fairfield, a Chicagoan. “She doesn’t want anyone to smoke. . . . Why, she didn’t even want any of the board of directors of the league to smoke, and many of us do.”

Gaston had moved from Harvey to Chicago in the early 1900s, living at 5519 South Kenwood Avenue, in Hyde Park. In January 1924, a streetcar struck her on Halsted Street. Afterward, her hospital treatment revealed that she had throat cancer, and she died on August 20th at the Hinsdale Sanitarium.

Despite all of Gaston’s efforts, annual cigarette sales in the United States had soared from 2.5 billion at the turn of the century to nearly 80 billion when she died. Lung cancer, which had been virtually unknown, was formally recognized as a disease for the first time in 1923 and became widespread in the 1930s. Cigarette consumption continued climbing, even after the U.S. Surgeon General issued a landmark report on its dangers in 1964. Sales peaked around 600 billion in 1980 and then began to drop, as the cigarette reacquired some traces of the stigma it had carried in the early 1900s. Gaston’s crusade may have failed during her lifetime, but Brandt says, “The reality is that Lucy Page Gaston saved some lives along the way.”