For more than half a century, Ralph Ellison and his literary executors held tightly to the author’s Invisible Man, refusing all attempts to turn the beloved 1952 novel into a play or a film. When the lights go up on Court Theatre’s world premiere in January, it will mark the first time Ellison’s nameless protagonist has lived outside the pages of this groundbreaking book about being black in 1930s America. We talked to Kenneth Warren, the University of Chicago’s resident Ellison scholar, and Invisible Man’s director, Christopher McElroen, about why a pre-civil-rights epic still resonates and how Court succeeded where so many failed.

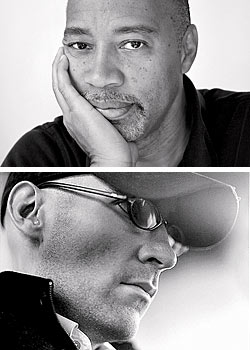

Kenneth Warren (top) and Christopher McElroen

Plenty of theatres have wanted to stage Invisible Man. How did a professional theatre company on the U. of C. campus get the nod?

CM: Part of our reaching out to the U. of C. was Ellison’s history. He taught there in the 1960s. Obviously Ken’s work was important to us, as was being able to explore this text in one of the best regional theatres in the country. And [Court’s artistic director] Charlie [Newell] had asked about doing an adaptation several times, so we knew there was interest.

KW: Oren Jacoby’s adaptation doesn’t contain a single word that isn’t in Ellison’s text. He did an extraordinary job of taking Ellison’s language, and only Ellison’s language, and turning it into theatre.

The novel seems to defy adaptation: Ellison wrote it in the rhythm of an improvised jazz riff, with scenes ranging from the rural South to the Harlem Renaissance. You could make a life’s work of studying the book. How can all of this be boiled down to two hours onstage?

KW: As excited as I was when I heard Court was doing this project, I was also dismayed, because how in the world could you pull it off? But I’ve been surprised and impressed by how much the script manages to get in while maintaining a clear dramatic arc.

CM: What we’ve done is go back to the novel continually. We try to tell a very clear story about the search for identity. And we’ve got a cast of ten, with a lot of doubling up on roles.

Much of the novel’s context—Jim Crow laws, for example—no longer exists, and the title character lives in the 1930s, when an African American man in the White House would have seemed like a fantasy. So why is Invisible Man still so compelling?

CM: The idea that everyone has walked into a room and felt invisible, that’s universal—and timeless.

KW: One of the terms Ellison hits continually is social responsibility, a concept that transcends time. [We all must figure out] what we owe one another. Even an invisible man has social responsibility.

GO Invisible Man runs Jan. 12 to Feb. 19 at Court Theatre; for info, courttheatre.org.

Photograph: (McElroen) Jason Goodman; Illustration: Tony DiMauro