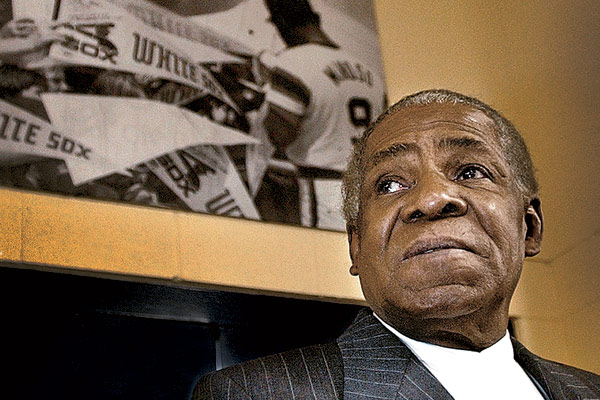

Miñoso (above, at a White Sox holiday party) likes to brag about having played professional baseball across seven decades. Now, he says, "I don't have what I used to have. It's not my time."

Related:

MORE COLUMNS BY EIG

The Bulls’ Secret Weapon: Tom Thibodeau »

Chicago Baseball Preview: The Most Dismal Season in 30 Years? »

Doak Ewing, Vintage Sports Film Collector »

Lovie Smith on Keeping His Cool »

Can Theo Epstein Deliver for the Cubs? »

Rosemont-based Riddell Seeks to Build a Safer Football Helmet »

Adam Greenberg Dreams of Making It Back to the Majors »

For the Chicago Comets, Blindness Is No Impediment to Tough Competition »

Laurie Schiller, the Most Successful College Coach You've Never Heard Of »

It was midspring, the hopeful season when every team clings to pennant dreams, and the fans at U.S. Cellular Field were either sitting quietly in their seats, passing beers fire-brigade-style, watching the White Sox fall apart against the Orioles, or strolling the concourse, carrying nacho platters that came loaded, breathtakingly, in upside-down baseball helmets.

It was just another day at the ballpark, in other words, until the fourth inning, when a ripple began to move through the concourse on the first-base side and the nearby fans looked around.

“What’s up, Minnie!” called out a security guard.

“How ya doin’, sweetie pie?” shouted a woman working a hot dog stand.

A middle-aged man bent over to tell his daughter, “You see that guy over there? That guy’s a legend.”

A woman in a black-and-white Sox jersey approached to ask if the legend would autograph her left breast.

Orestes “Minnie” Miñoso, a.k.a. the Cuban Comet, is 86 years old now. Some say he’s really 88. He has been a White Sox employee so long that the human resources department can’t say exactly when he went on the payroll. In his role as ambassador, he attends about 60 games a year, greeting fans and strolling through the crowd, making friends. Some people are so good at making friends they deserve to be paid for it, and Miñoso is one of them.

As he walked to the center-field bleachers on the day of the Orioles game, a knot of people formed around him. It was the 60th anniversary of his first game with the Sox, when he had become the team’s first black player. Miñoso had smiles, small talk, and autographs for everyone.

“Sixty years?” he said. “It’s like 60 days to me.”

At 86, we should all have his energy. We should all be so happy. We should all be asked to sign breasts.

Miñoso still cuts a dashing figure. His compact frame looks almost as lean and muscled as it did in the 1950s, when he ripped line drives into the alleys and shot around the bases, as electrifying a player as Chicagoans have ever seen. His hands remain big and strong, his forearms thick and ropelike. His hair has gone gray, but it hasn’t thinned at all, and his expression, always famously happy, hasn’t changed a bit.

Some of baseball’s biggest stars became poor sports in their later years. DiMaggio got crotchety. Mantle got surly. Williams got ornery. (Although these players were always somewhat crotchety, surly, and ornery, respectively, old age made them worse.) But the second-tier stars like Miñoso, the ones who had to work harder, who made less money, often show greater appreciation for the blessings the sport bestowed on them. Miñoso carries on like a man who won the lottery and then bet it all on a horse, only to win again.

* * *

Photograph: Zbigniew Bzdak/Chicago Tribune

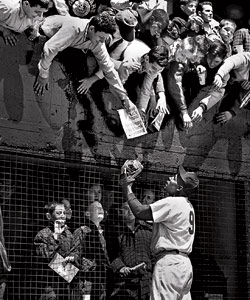

Miñoso mingles with fans at Comiskey Park in the early 1960s. Half a century later, he’s still making friends.He was born in Perico, Cuba, just outside Havana. His birth name was Saturnino Orestes Arrieta, but he was often mistaken for his older half brother, who also played ball and whose last name was Miñoso. Later, in the United States, sportswriters called him Minnie, just for the sake of alliteration, leaving him with a girl’s first name and his brother’s last name. He didn’t care as long as he got to play.

When he was about 12, Miñoso quit school and went to work in the sugar cane fields, like his father. The work made him strong, if not happy. When he found out his employer didn’t have a youth baseball team, he organized one and named himself manager. Miñoso was so likable, even then, that no one complained when he fined his young players 50 centavos each time they missed a bunt sign.

He patterned his game after that of Cuban superstar Martin Dihigo. He lined balls to the opposite field and ran like crazy, driving pitchers and catchers to distraction. When he was 18, he latched on with Havana’s Ambrosia Candy team, earning a paltry $2 a game plus $8 a week for working in Ambrosia’s garage. After that, he rolled cigars for Partagas and played for the company team. Finally, at 20, he latched on with Marianao, one of Cuba’s best teams, where he made $200 a month. He didn’t need a second job anymore.

Related:

MORE COLUMNS BY EIG

The Bulls’ Secret Weapon: Tom Thibodeau »

Chicago Baseball Preview: The Most Dismal Season in 30 Years? »

Doak Ewing, Vintage Sports Film Collector »

Lovie Smith on Keeping His Cool »

Can Theo Epstein Deliver for the Cubs? »

Rosemont-based Riddell Seeks to Build a Safer Football Helmet »

Adam Greenberg Dreams of Making It Back to the Majors »

For the Chicago Comets, Blindness Is No Impediment to Tough Competition »

Laurie Schiller, the Most Successful College Coach You've Never Heard Of »

Major-league baseball was still segregated in 1946 when Miñoso came to the United States, signing a contract to play for the New York Cubans, of the Negro leagues. One year later, Jackie Robinson integrated the game. Miñoso had his chance. In 1949, he made his big-league debut with the Cleveland Indians; in 1951, the Indians traded him to the White Sox.

In his first at-bat of his first game for the Sox, he faced Vic Raschi of the Yankees. One of Miñoso’s teammates warned him Raschi threw a good curve and a good slider.

“Well, I’m going to swing at the first pitch, whatever it is,” he said.

He did—and hit it 415 feet for a home run.

“So,” I asked him, 60 years later, “what was the pitch? Fastball? Curve?”

“It was a baseball, I think.” He smiled. A line he’s probably used 5,000 times.

I asked if anyone had treated him badly because he was the team’s first black player.

“From the first day here,” he said, “people respected me.”

Did it make any difference that he was Cuban and not African American?

“Nah. You see the person, you see white or black. It don’t make any difference where you come from. I’m black.”

Though he spoke little English, he became a favorite of fans. With Chico Carrasquel, Jim Busby, and Miñoso all stealing bases and fielding slickly, the Go-Go Sox were a thrill to watch. While the Yankees had the big-name, high-priced sluggers, the Sox had hungry hustlers. In his rookie year, Miñoso was hit by pitches a league-leading 16 times. It wasn’t that opposing pitchers wanted to hurt him; it was that Miñoso wanted to get hit. Anything to get on base. Anything to help the team. Other players may have been more talented, more intelligent, he says, but no player in the history of the game ever hustled more.

The Sox of the 1950s were some of the best teams ever to play baseball in Chicago. Unfortunately, the Yankees were usually better. Though segregation shortened Miñoso’s career by perhaps half a decade, he still finished with near–Hall of Fame numbers: a .298 batting average, 186 home runs, and 1,023 runs batted in.

* * *

Photograph: Ray Gora/Chicago Tribune

Related:

MORE COLUMNS BY EIG

The Bulls’ Secret Weapon: Tom Thibodeau »

Chicago Baseball Preview: The Most Dismal Season in 30 Years? »

Doak Ewing, Vintage Sports Film Collector »

Lovie Smith on Keeping His Cool »

Can Theo Epstein Deliver for the Cubs? »

Rosemont-based Riddell Seeks to Build a Safer Football Helmet »

Adam Greenberg Dreams of Making It Back to the Majors »

For the Chicago Comets, Blindness Is No Impediment to Tough Competition »

Laurie Schiller, the Most Successful College Coach You've Never Heard Of »

After retiring from big-league baseball, he played eight more seasons in the Mexican League. In 1976, Bill Veeck brought him back to Chicago as a coach and talked him into playing two games, the first as a designated hitter, the second as a pinch hitter. At age 51 (or 53), he managed to scratch out one hit. In 1980, at age 55 (or 57), he made two more plate appearances. By then, it had become a stunt. But the fans loved it, and Minnie, as usual, didn’t mind.

In 1993, at age 68 (or 70), he managed to hit a ground-ball out for the minor-league St. Paul Saints. A decade later, at age 78 (or 80), he stepped to the plate one last time for the Saints and drew a walk.

Now he brags of having played professional baseball across seven decades. But that’s not all he brags about. He’s also proud of his children. He’s proud of his wife of 21 years, Sharon Rice-Miñoso, who serves as his agent and manager. They live in a lakefront high-rise on the North Side. He’s proud that he can still do 150 sit-ups each morning.

Everywhere he goes now, every time he walks the concourse at U.S. Cellular Field or sits at the bar at Sluggers in Wrigleyville or walks through the airport in his black Minnie Miñoso ball cap, he gets the same questions: Who was the toughest pitcher you ever faced? He answers Hoyt Wilhelm, the knuckleballer. Who was the best all-around player you ever saw? He says Willie Mays.

As I stood with him one day on the field before a game, batting practice under way, the splendid sound of bat on ball pealing through the park, I couldn’t help but ask him another one of those routine questions: Does he ever feel like grabbing a bat and taking a few swings? Try to make it eight decades?

“No,” he said, “I’m not going to pretend. I don’t have what I used to have. It’s not my time.”

I wanted to disagree. I think it’s still very much Miñoso’s time. Instead, I asked another question: What would you have been if you hadn’t been a ballplayer?

He paused and looked me in the eyes. It was the first time all day that he didn’t have an easy answer.

Finally, he said, “I don’t know.”

He paused again.

“But I know one thing: I’d be a good gentleman.”