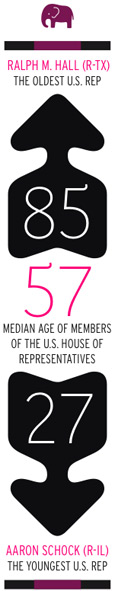

Aaron Schock is in a hurry. It’s a Tuesday in early December, and the 27-year-old politician is a month away from becoming the nation’s youngest congressman—a spot of GOP promise in a blue year. Washingtonian magazine has named him to its “Guest List” of the eight people it would most like to invite for drinks and conversation. He’s flying to Boston at 3 p.m. for a new member orientation. In the meantime, he has to pack his bags and interview a prospective staffer at the airport.

But this morning, he’s still Peoria’s Kid Schock, as one paper called him, and Kid Schock is the guest on At Issue, a public television talk show in his hometown. Sitting in the riverside studio with the host, H. Wayne Wilson, Schock talks about the difficulty of funding Medicare and Social Security. It’s not that he wants to abolish the programs; he’s worried they won’t be around when he needs them. “Coming into Congress at 27 years old, I’m not concerned about these programs for the next decade; I’m concerned about them for the next generation,” he says into the camera. “I hope that they’re there when I’m ready to retire.”

That’s the kind of talk you’d expect from the first congressman born in the 1980s. While voters under 30 have been called the “most Democratic generation in history”—Obama won 69 percent of their votes—Republicans have suffered the stigma as yesterday’s party. The GOP needs a politician who can appeal to Generation Y: The Illinois GOP thinks it might have it in Schock, who has been Central Illinois’s “It Guy” ever since he was elected to the Peoria Board of Education at 19. “[Schock’s success] says to people in this state that the Republican Party values young people,” says the Illinois House minority leader, Tom Cross.

“He takes all the air out of the room, politically, here in Peoria,” says Bill Dennis, who writes the blog Peoria Pundit. “Either you think he’s the greatest thing ever, or you’re deeply suspicious of him. I’m suspicious of him because he’s so eager to get ahead in office.”

Schock’s youth has made him the butt of criticism. Tall, toothy, his already-thinning hair swept up in a tousled ’do, he has been mocked as “Lil’ Aaron” and “Doogie Howser.” When he proposed threatening China by selling nuclear missiles to Taiwan, a rival candidate for Congress called him “naïve” and “inexperienced.” Schock dropped the idea.

After the TV interview, we jump into Schock’s Land Rover. “I hope this doesn’t make you uncomfortable,” he says, “but I’m going to have to stop back at my house and pack.” He spends most of the drive on his BlackBerry, talking to a staffer in Washington about his inaugural party. “Should I try to get a committee room, or is that not doable, because I’m in the minority? . . . No, I don’t like the Capitol Hill Club. I like the Hay-Adams.”

Schock lives on a working-class block in Peoria, in a house he bought for $52,000 and rehabbed himself. “In the six years I’ve lived here, I’ve turned on the oven twice,” he says. “I go to events almost every night.”

While Schock is upstairs packing, I sit on the un-broken-in couch and click on his giant TV. It’s already tuned to Fox News. Twenty minutes later, he returns with a suitcase, still trying to stuff in a pair of running shoes, a mini DVD player, and a U.S. News and World Report.

Schock has been in a hurry since he was 12. In middle school, his father, a physician, bought him an IBM PC Jr. After learning to program it, he offered to help a bookstore owner maintain his database. “He said, ‘I can’t hire you because you’re 12 years old,’” Schock recalls. “I said, ‘I’ll set up a contracting business and you can hire my company.’ Then, in seventh grade, I started working for a ticket broker in Woodstock. I had 13 credit cards, and on a given weekend I’d buy a couple hundred tickets.”

Schock parlayed his earnings into tech stocks. A few days after turning 18, he bought his first piece of real estate—110 acres of farmland he hoped to mine for gravel. (He sold it to the Greater Peoria Sanitary District at a 170 percent profit.) By his junior year, Schock had satisfied all his academic requirements and was ready to leave school. But Richwoods High School told him he needed a fourth year of physical education. Outraged by this waste of his time, Schock ran for the school board. The board president challenged his petitions, knocking him off the ballot. Undeterred, Schock mounted a write-in campaign—and unseated her.

Four years later, while a student at Bradley in Peoria, he ran for the state legislature, defeating an incumbent in a low-income, Democratic-leaning district. Despite a conservative record—“I’m pro-life, pro-family”—Schock won 39 percent of the African American vote in his next run. He did it by paying attention to the black community’s needs, says Eric Turner, a Peoria city councilman. Once elected, he brought home funding for Peoria schools, and helped a small cab company with reimbursements for driving Medicare patients to the doctor. During a two-and-a-half-minute speech to the Republican National Convention, Schock talked about his party’s outreach to “inner-city residents not accustomed to seeing Republican candidates.”

Back in the Land Rover, Schock makes a pit stop at the airport, so he can check his luggage, before heading to lunch at One World Café, one of the few ethnic restaurants in his Middle American hometown. “That’s one thing I’m looking forward to in Washington,” he says. “Thai food.”

Schock has another appointment at 1:30—he’s interviewing a potential staffer at the airport. As the time nears, he begins tapping his thumb. “I don’t like to sit around,” he explains. But, because of his youth, he’ll have to do some sitting in the House of Representatives. Schock may be the Illinois GOP’s hottest prospect, but he won’t turn 30 in time for next year’s Senate election. Does that frustrate him? Maybe. But he’ll be ready for his next chance to move up. “Things could change,” he says, heading toward the Land Rover. “In politics, you never know who’s going to die, retire, or—in Illinois—get indicted.”