“I choose to do cartoons because that’s the art form closest to how I actually see the world,” says Ivan Brunetti, the illustrator behind eight New Yorker covers and creator of a definitive new guide to crafting comics. The Columbia College professor and University of Chicago alum, 43, lives and draws in Jefferson Park, where he’s assisted by his two muses, cats Linus and Schroeder. We dropped by Brunetti’s studio to observe his process, which he details in Cartooning: Philosophy and Practice (Yale University Press, $13), out March 29th. PLUS: Brunetti appears April 1st at Chicago Comics, 3244 N. Clark St.; 773-528-1983.

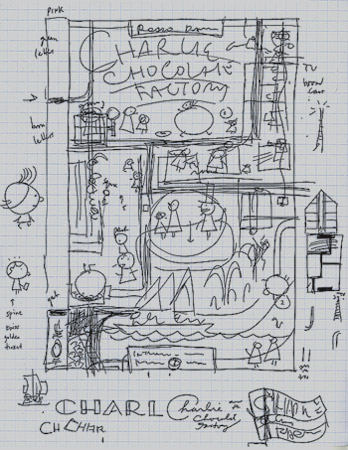

STEP 1: Penguin asked Brunetti to create a cover for its new edition of Roald Dahl’s Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, part of a series of literary classics with art by today’s graphic novelists. After doodling on Post-its, he sketched a layout in black pen, showing the different rooms where the naughty children meet their fates. Brunetti bedecks his house with curio cabinets filled with Mickey Mouse dolls, Pinocchios, and vintage toys, so a project catering to his inner child wasn’t far-fetched.

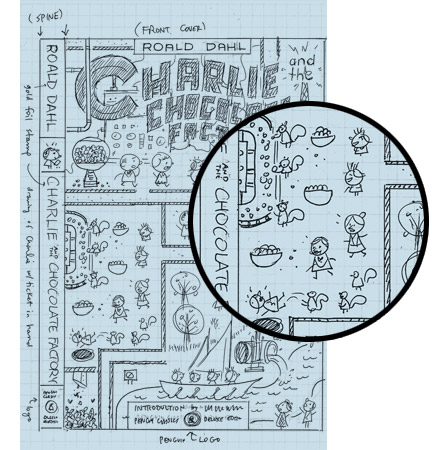

STEP 2: Key elements of Dahl’s book become clear in the next iteration—the chocolate room, inventing room, nut-sorting room, and television room take shape. Scribbles in the lower left corner represent the garbage chute, complete with circling flies. Brunetti says that there are three necessary tools for cartooning: pencil, paper, life. Even the flies have been extracted from his biography—Brunetti’s past jobs include fast-food cook, dishwasher, and janitor. “I have yet to make a living as an artist,” he says.

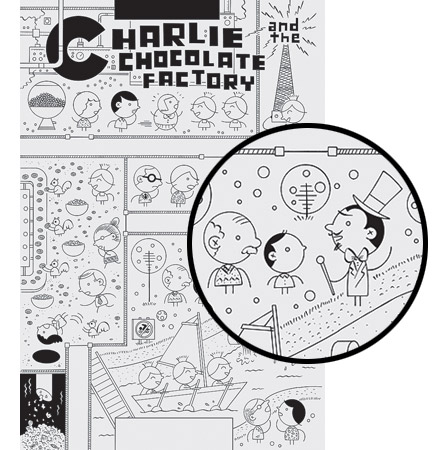

STEP 3: Using India ink and crow-quill pens, Brunetti next renders his design on 18-by-24-inch Bristol board. The additional workspace allows him to create more details. Lifelong myopia has left him with a complete lack of depth perception; notice the absence of shadows. “I see everything really flat, so that’s how I draw, too,” he says.

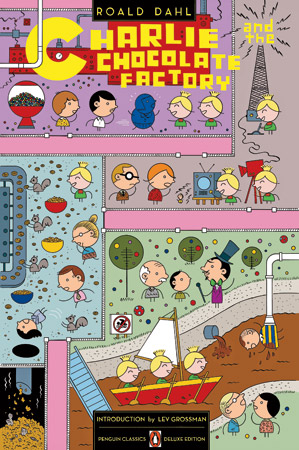

STEP 4: Brunetti aimed to portray Willy Wonka’s factory as the author intended: white, pristine, almost surgical. When he accidentally clicked the wrong icon while making Photoshop adjustments, the picture snapped into color and became more appealing to both Brunetti and his wife, Laura. Thus he conveys the sterility of his scenescape by “making it as geometric as possible.”