“The violet sucks,” says Robbie Telfer, using the same fighting words he chose back in February, when he took to public radio to launch his quixotic campaign to sack Illinois’s longtime state flower. Cruising south on I-57 toward Bourbonnais, the floral firebrand can’t resist slinging mud, denouncing the violet as a do-nothing incumbent that has “lost touch with the people.”

“I don’t see anything particularly Illinois about it,” says the 34-year-old-poet-turned-citizen-activist, a Logan Square resident, suddenly striking a more conciliatory tone. Telfer thinks that the rangy, broad-blossomed, pink-petaled Kankakee mallow, the only known wildflower whose native habitat is in Illinois, would be a far more interesting choice than the violet, which is also the state flower of New Jersey, Rhode Island, and—sin of all sins—Wisconsin.

“It’s very Illinois,” he says of the proud mallow, which he first learned about in 2013, when a sudden interest in gardening led him to join the Illinois Native Plant Society. “It’s a friend to the other shrubs and prairie flowers. It looks very native.”

There’s only one problem: His proposed alternative might be extinct.

More than 5,000 mallows grew on Langham Island in the Kankakee River as recently as 2002, according to Trevor Edmonson, a restoration specialist at Midewin National Tallgrass Prairie and a member of Friends of Langham Island. But then state funds to clear the 30-acre island of honeysuckle and other invasive plants dried up. Without the necessary care, the mallow faded into obscurity. Its rareness, though, has given the sweet-smelling flower (scientific name Iliamna remota) an almost rock-star status. Like Elvis fans hoping to catch a glimpse of the King walking around Graceland, college classes and flower societies from across the state trek to Langham Island in search of the prized plant. But until last fall, no traces were found.

Telfer and I speed past farmhouses to the mallow’s home turf in Kankakee River State Park, off Route 102 in Bourbonnais, where we find the rugged-looking Edmonson waiting for us with a small steel rowboat. It’s a crisp but pleasant afternoon in early March, and the sun is shining bright. Telfer, whose glasses and mussed hair give off a crazy-professor vibe, slips out of his sneakers and into rubber boots. We push the craft into the icy waters and enjoy the pristine winterscape as we paddle 30 or so yards to Langham Island.

Once ashore, we pass a hidden beaver dam and trudge along a small trail that cuts through endless tangles of honeysuckle. “If you were standing here last August, you weren’t able to see the river,” says Edmonson as we reach a clearing on the southwest section of the island. “We cleared off most of this bank. It was densely thick.”

Like an uninvited relative who moved in and never left, honeysuckle came to the island decades ago, probably by way of birds carrying seeds from the East Coast. Its rampant overgrowth blocked out the intense sunlight that mallows need to thrive. To restore the habitat, every month volunteers from Friends of Langham Island spend a day clearing the brush and “rolling burn piles,” as Edmonson describes it, twirling small fires across the ground, mostly near the oak trees where the mallows used to grow.

“Brushfires do what Native Americans or lightning did in the past,” Telfer says. “Fires along the prairie were essential for cleaning out dead plants and turning on the germination of the seeds.”

Edmonson points to a burn circle near the ridge. “We’ve already seen [mallow shoots] back in November when it got warm. We had been doing brushfires, and the next day we saw the sprouts.”

Does that mean the mallow will definitely be back?

“If we were betting, it would be a good safe bet,” says Telfer, who points out that the native seeds can sit in waiting for decades underground until the heat from a controlled burn gives the signal that they will have the necessary light and room to grow.

Assuming that the bet pays off, Telfer has a potential ally in his quest to make the mallow the Land of Lincoln’s top flower. Representative Kate Cloonan (D-Kankakee), whose 79th District includes Langham Island, seems amenable to at least pushing an honorary resolution to bring attention to the plant as an only-in-Illinois treasure. As far as taking the matter to the General Assembly, that remains to be seen.

“She said this year’s legislation is pretty locked up,” says the straight-faced Telfer, who teaches and performs poetry at schools and festivals around the world and is a former organizer of the youth poetry slam Louder Than a Bomb. “It would have to be proposed next year. Considering that it takes hundreds of years for prairie habitats [like Langham Island] to be restored, we have the time.”

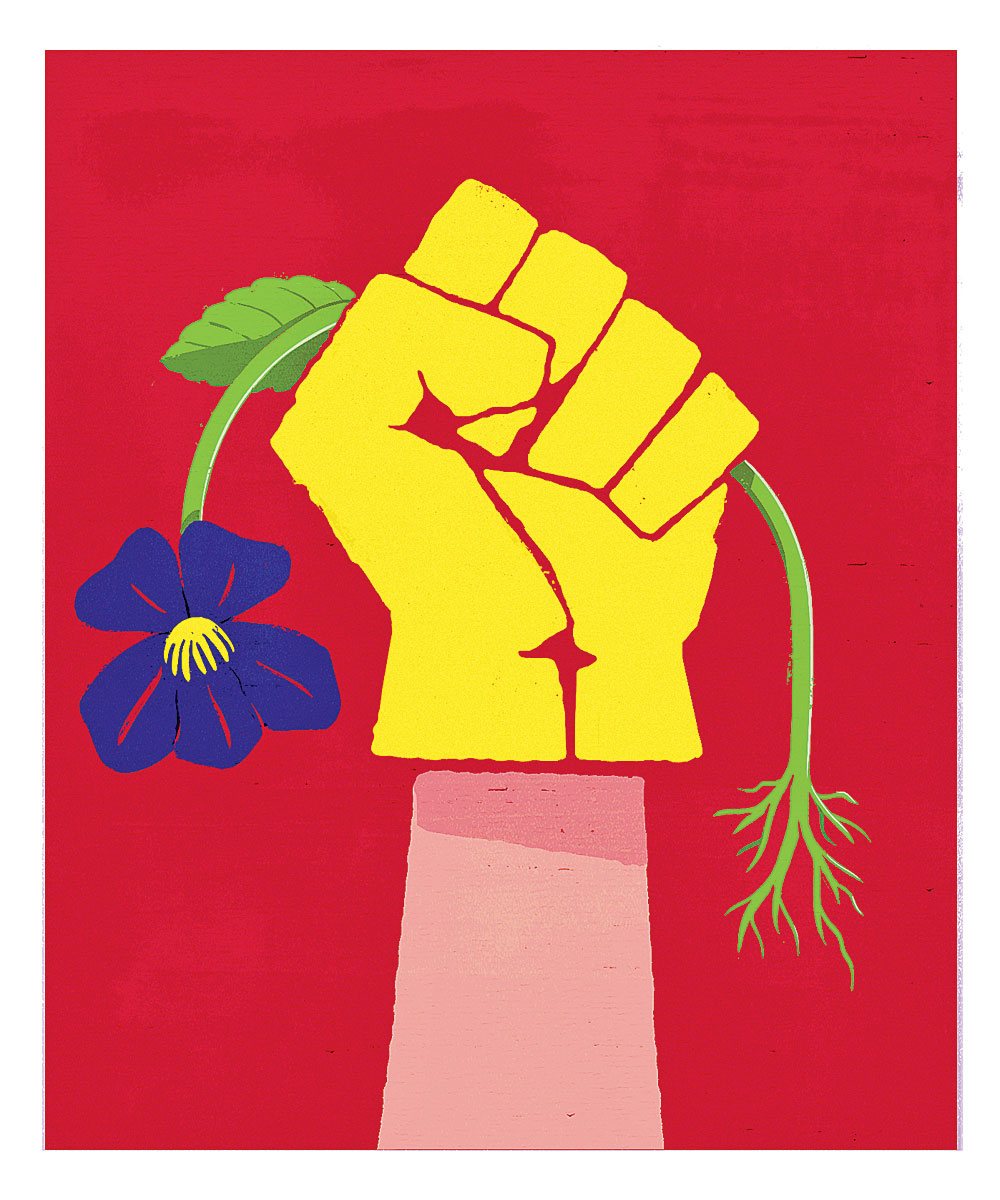

Telfer certainly has the grassroots campaigning covered. He’s produced retro-cool Eisenhower-era buttons emblazoned with the catchy slogan “Don’t Be Shallow, Vote for Mallow.” They’ll be distributed at plant shows and other community events through Habitat 2030, a volunteer organization that restores local parks, preserves, and other natural spaces.

Of course, everyone who enters politics has an angle. And to his credit, Telfer makes no attempt to hide his real agenda. “To be honest, I don’t care if the campaign is successful or not. I’d like this to be a conversation starter so we can bring attention to all of the plants and animals that are threatened to be wiped out. As we’re talking, I’m sure a bird species just went extinct, you know?”

Only time will tell if Telfer can pull an upset and unseat the humdrum violet. But he says he just might use the same cutthroat campaign tactics to take down other unworthy state symbols. Next on his hit list? The state bird, which, if you didn’t know, is the cardinal. “I’d nominate the prairie hen,” Telfer says. “They are amazing. They look like a grouse and do this crazy, intricate mating dance. They are much more interesting.”

Maybe in between cutting funds to state parks and cleaning up the pension mess, our newly elected governor can finally take a stand on these vital issues. What better way to jump-start an Illinois revival than by replacing our lame state symbols?

The ball is in your court, Rauner.