Photography BY Erika Dufour

They infest our lakes and rivers, disrupt our skies, ravage our forests, and devour our gardens. Sometimes these non-native plants and animals arrive through human carelessness, sometimes by human design, but without natural predators, many spread rapidly to wreak havoc on the local ecosystem.

Nationally, close to half the 958 plants and animals listed as threatened or endangered are at risk primarily because of these unwelcome invaders, which every year cause an estimated $138 billion in damage.

Several recent frightful incursions here—by the Asian long-horned beetle, the silver carp, and the emerald ash borer—prompted us to seek dossiers from the Field Museum, which houses one of the world's largest collections of biological and anthropological specimens. Here are some of the most notorious.

NAME: Silver carp (Hypophthalmichthys molitrix)

NAME: Silver carp (Hypophthalmichthys molitrix)

ORIGIN: Eurasia

DATE INTRODUCED: 1973

HOW IT GOT HERE: Imported to control algae in aquaculture ponds; escaped into the Mississippi River in the early 1990s

"Right now, the silver carp is probably the number-one threat [to the aquatic ecosystem], in terms of invasive species," says Philip Willink, a fish biologist at the Field Museum. Originally brought here by catfish farmers to rid their ponds of algae, the fish escaped into the Mississippi River basin after storms flooded the ponds. Though silver carp—and their close relative, the bighead—haven't yet spread to the Great Lakes, they have been making their way up the Illinois River and are now within 50 miles of Lake Michigan, contained only by an electrical barrier built by the Army Corps of Engineers on the Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal. Along the way, these large, ugly filter-feeders have been devouring plankton—a vital source of food for larval native fishes. "They're basically wiping out the bottom of the food chain," says Willink. They're also nuisances to boaters because they often jump out of the water at the sound of boat motors, occasionally injuring the people on board.

THE FIGHT: So far, the electrical barrier has kept silver carp from infesting Lake Michigan, but scientists worry that these feisty and resilient monsters could get through.

NAME: Sea lamprey (Petromyzon marinus)

NAME: Sea lamprey (Petromyzon marinus)

ORIGIN: Atlantic Ocean

DATE INTRODUCED: 1835 (Lake Ontario); 1921 (Lake Erie)

HOW IT GOT HERE: Arrived in Great Lakes through Welland Canal

With its suction-cup mouth filled with sharp, hooked teeth, this parasitic, snakelike invader attaches itself to a host fish, chews a small hole, and feeds off the victim's blood, either killing the host or severely weakening it. Lampreys are believed to be responsible for the declining lake trout and salmon populations, particularly in the Great Lakes. By wiping out large numbers of lake trout, which are indigenous predators, sea lampreys have allowed other invasive prey species, such as rainbow smelt and alewives, to flourish without any competition. Deterioration in the stock of large fish has also hurt commercial and sport fishing across the Great Lakes.

THE FIGHT: Sea lampreys are one of the few aquatic invasives that have been kept in check. Scientists use a chemical toxin specific to lampreys (a mixture of trifluoromethyl and nitrophenol, or TFM) in infested waters and in potential breeding areas. They are also experimenting with pheromones to disrupt lamprey migrations and mating.

NAME: Round goby (Neogobius melanostomus)

NAME: Round goby (Neogobius melanostomus)

ORIGIN: Eurasia

DATE INTRODUCED: 1990

HOW IT GOT HERE: Ballast water

This small bottom dweller, originally from the Black and Caspian seas, first infested the St. Clair River and then the Great Lakes. Unfortunately, says Willink, round gobies are now "quite possibly the most abundant fish in Chicago." They are extremely aggressive, with large appetites that push out other bottom feeders and nesters. "Mottled sculpins are disappearing from Lake Michigan and darters are also threatened," says Willink. Gobies are also nuisances to perch anglers because they often eat their bait. On the plus side, gobies eat zebra mussels, though not fast enough to do much good. Gobies are also a preferred food for smallmouth bass and walleye, helping these species to thrive.

THE FIGHT: Working with the Army Corps of Engineers, scientists have been testing electrical barriers to contain the spread of gobies to noninfested waters. So far, says Willink, "gobies spread so fast—nobody really knows what to do."

NAME: Asian lady beetle (Harmonia axyridis)

NAME: Asian lady beetle (Harmonia axyridis)

ORIGIN: Northeast Asia

DATE INTRODUCED: 1916, but first populations not found in the U.S. until 1988, in Louisiana

HOW IT GOT HERE: Introduced to control plant-eating aphids and other pests

A cousin of the ladybug, the Asian lady beetle looks a lot like our cute, black-spotted red critters. But these insects, which hit Chicago about five years ago, are downright mean, especially to their North American relatives. "Not only have they been aggressively crowding them out; they've been eating them—plus whatever else they can get their jaws on," says Daniel Summers, the Field Museum's collection manager for insects. Including humans. (The bugs occasionally bite, but they're not poisonous.) Unlike most ladybug species, which hibernate by burrowing in leaf litter, Asian ladybugs have the annoying habit of wandering indoors in the wintertime.

THE FIGHT: More a household pest than a serious environmental problem, the beetles are best controlled by spraying pyrethroid insecticides outside buildings.

NAME: Japanese beetle (Popillia japonica)

NAME: Japanese beetle (Popillia japonica)

ORIGIN: Japan

DATE INTRODUCED: 1916

HOW IT GOT HERE: Arrived as a stowaway in iris bulbs shipped from Japan

First found some 90 years ago in a New Jersey nursery, these metallic-green insects with copper-colored wings are voracious eaters of ornamental trees and shrubs, as well as vegetable crops. "They love to eat roses," says Summers. "But they also feed on 300 different types of plants." Adult beetles, which are around a half-inch long, burrow inside foliage and chew on the leaf tissue between the veins, leaving leaf skeletons. Equally hungry larvae—inch-long milky-white grubs with brown heads—hide in wet, shady sections of grass, feeding on the roots.

THE FIGHT: Traps help detect the emergence of these garden pests but are not recommended for controlling their spread, since the pheromone bait attracts nearby beetles. Handpicking is effective for small populations, and chemical insecticides help control large populations, though sometimes at a risk to nonpests, such as honeybees.

NAME: Emerald ash borer (Agrilus planipennis)

NAME: Emerald ash borer (Agrilus planipennis)

ORIGIN: Asia

DATE INTRODUCED: 2002; discovered in Illinois in 2006

HOW IT GOT HERE: Arrived in imported cargo

The emerald ash borer arrived last year in Kane County and spread as far as several North Shore towns, setting off alarms of an arboreal catastrophe. These tiny green beetles had already killed an estimated 20 million ash trees in Michigan, Indiana, and Ohio, making it "a much greater threat than the Asian long-horn," says Summers. The insect feeds only on ash trees—which make up roughly 20 percent of the trees in the Chicago area. Adult borers feast on ash foliage, causing little damage. But the larvae feed on inner bark, cutting off the flow of nutrients and water to the trees, eventually killing them.

THE FIGHT: The state's department of agriculture set up ash borer quarantines in several northeastern Illinois counties to stop the movement of infected firewood, logs, and nursery trees. Entomologists are also considering releasing the borer's native nemesis: a stingless wasp that eats the beetle's eggs and larvae.

NAME: Common teasel (Dipsacus sylvestris)

NAME: Common teasel (Dipsacus sylvestris)

ORIGIN: Europe

DATE INTRODUCED: 1700s

HOW IT GOT HERE: through contaminated seeds

These stalky, prickly stemmed biennial weeds, which can grow eight to ten feet tall when flowering, have spread rapidly over the past 20 to 30 years, largely in areas disturbed by development. "Teasels pretty much come in where there's opportunity," says Laurel Ross, an urban conservationist at the Field Museum. "Highways and roadways are an opportunity—they're big open areas with lots of sun." Because its lilac or white flowers develop into large oval seed cases whose spines were used for teasing cloth, the plant is also known as a gypsy comb. A single teasel plant produces thousands of seeds, most of which will germinate.

THE FIGHT: Applying herbicide to the rosette kills the plant's roots and prevents it from resprouting. Flowering stalks may be cut down, but seeds often continue to develop and mature even after cutting. Remove the cut stalks to prevent the seeds from dispersing.

NAME: Monk parakeet (Myiopsitta monachus)

NAME: Monk parakeet (Myiopsitta monachus)

ORIGIN: South America

DATE INTRODUCED: Late 1960s

HOW IT GOT HERE: Escaped from O'Hare

As the story goes, the owner of an exotic-pet store released a crate of these Argentinean parakeets at O'Hare because he lacked proper permits. (Variant: The birds simply escaped.) Whatever happened, by the late 1970s monk parakeets had taken up residence around Hyde Park, much to the delight of former mayor Harold Washington, who considered them good-luck omens. Doug Stotz, a conservation ornithologist at the Field Museum, says these gray-hooded bright-green birds may be cute but "they've become pests in their own right. They're seed predators, and they damage crops in agricultural areas [in their native South America]." In urban areas, the birds can be nuisances: They're incessantly vocal in the daytime and build nests around electric transformers, increasing the risk of fires.

THE FIGHT: In the early 1970s, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service captured about half the wild monks in the United States, but the population has since rebounded. Attempts to capture or kill the parakeets here have been unsuccessful because of political pressure by animal-rights groups and bird lovers.

NAME: Asian long-horned beetle (Anoplophora glabripennis)

NAME: Asian long-horned beetle (Anoplophora glabripennis)

ORIGIN: Asia

DATE INTRODUCED: 1996

HOW IT GOT HERE: Arrived in cargo crates from Asia

First seen in the area in 1998 and now thought to have been eradicated here, these black beetles with white spots and long ringed antennae went on an eight-year tree-killing spree, wiping out 1,771 trees in the Chicago area, mostly in the Ravenswood neighborhood, and more than 31,000 trees in other affected areas in Illinois, New York, and New Jersey. Unlike the latest invasive menace, the selective emerald ash borer, the Asian long-horned beetles "went for just about everything—elms, maples, oaks, magnolias, ornamental trees—whatever hardwoods happened to be around," says the Field's Summers.

THE FIGHT: With no known chemical or biological defense against the voracious insect, infested areas were quarantined and affected trees were chopped down and burned to destroy the eggs buried in the wood.

NAME: Purple loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria)

NAME: Purple loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria)

ORIGIN: Europe and Asia

DATE INTRODUCED: Early 1800s; arrived in Illinois in the 1940s or 1950s

HOW IT GOT HERE: brought as an ornamental plant and herb; the seeds also spread through the ballast of ships and sheep's wool.

This magenta-flowered perennial may look pretty, but it's "a real scary weed," says the Field's Ross. Capable of growing to heights of three to seven feet, purple loosestrife aggressively overwhelms local wetlands, crowding out native grasses and destroying the habitats for some amphibians and waterfowl. "You lose the birds, you lose the bugs, you lose the native wetland plants," says Ross. "It becomes a big wet area of purple loosestrife." Nationwide, purple loose-strife spreads across an estimated one million acres of wetlands each year, mainly because it produces thousands, sometimes millions, of seeds annually and can even reproduce from roots and broken stems.

THE FIGHT: Purple loosestrife has no natural predators here, so biologists have imported three types of leaf- and root-eating beetles and a flower-eating weevil from Europe and Asia to devour this menace.

NAME: Garlic mustard (Alliaria petiolata)

NAME: Garlic mustard (Alliaria petiolata)

ORIGIN: Europe

DATE INTRODUCED: 1800s

HOW IT GOT HERE: Introduced for cooking and medicinal purposes

With a weak single stem, scalloped dark green leaves, and white flowers, garlic mustard looks harmless enough, but it has aggressively made its way across the landscape, snuffing out almost everything in its path. "If you have one of these, you have 50," says Ross. Botanists say the territorial takeover permanently alters the habitat's suitability for insects, birds, and mammals. The weed also kills the fungi that help plants and trees take nutrients from the soil, slowly leading to local plant extinctions. The name comes from the invader's pungent odor—like onion or garlic when crushed.

THE FIGHT: Garlic mustard has no natural predators here, so, Ross says, burning, herbicides, and handpicking are the three most effective methods to control the weed. "But you have to get it before the seeds are ripe, usually while it's flowering," she says.

NAME: Gypsy moth (Lymantria dispar)

NAME: Gypsy moth (Lymantria dispar)

ORIGIN: Eurasia

DATE INTRODUCED: 1869

HOW IT GOT HERE: Imported for silk production

This gluttonous pest, which devours forests, initially escaped through the window of a French scientist living in Massachusetts who was trying to mate the moths with silkworms. With no natural enemies, the moths spread across the country. Around Chicago, gypsy moths are found mainly in the northern suburbs, though they have been found as far south as Peoria. Female gypsy moths, which are white or cream-colored with two-inch wingspans, lay egg masses that produce up to 1,000 larvae, or caterpillars, which devour the tree foliage. Gypsy moth larvae prefer oaks, but feed on more than 500 species of hardwoods and shrubs. A two-inch caterpillar can eat more than a square yard of leaves. Each year, the moths defoliate around two million acres of forests nationwide.

THE FIGHT: Using helicopters, the state's agriculture department sprays infested areas with Btk (Bacillus thuringiensis kurstaki), a bacterium that is not toxic to humans and other animals, insects, and birds, but is lethal to the gypsy larvae. Scientists also use pheromone traps to disrupt the mating of adult moths.

NAME: Common buckthorn (Rhamnus cathartica)

NAME: Common buckthorn (Rhamnus cathartica)

ORIGIN: Europe

DATE INTRODUCED: 1800s

HOW IT GOT HERE: Introduced as an ornamental shrub

Buckthorns start small but grow into trees around 20 feet tall. Fast growing in either shade or sun, pest resistant, and with thick egg-shaped leaves and thorn-tipped twigs, buckthorns were once popular hedge shrubs. Thanks to birds and squirrels, which eat buckthorn berries and distribute the seeds through their droppings, buckthorns have taken over large swaths of woodlands, forming dense, impenetrable thickets that crowd out native shrubs and plants and deprive those on the forest floor of vital sunlight, eventually wiping them out.

THE FIGHT: Buckthorns are tough to kill. The larger ones can be cut down and the stumps treated with herbicide; but buckthorns regenerate quickly from roots, so, Ross says, burning buckthorns when they are small is an effective control.

NAME: Zebra mussel (Dreissena polymorpha)

NAME: Zebra mussel (Dreissena polymorpha)

ORIGIN: Eurasia

DATE INTRODUCED: 1988

HOW IT GOT HERE: Ballast water

Named for its zebra-like stripes and originally found in freshwater lakes in Russia, the zebra mussel has spread to all five Great Lakes and numerous inland waters. In each new spot, these menaces multiply rapidly and create massive, layered colonies on hard surfaces—smothering native mussels and clogging water intake pipes, causing water-supply problems and costing millions of dollars. In addition, these ferocious eaters feed on tiny animals and algae, a vital part of the food supply for larval fish. On the other hand, adds the Field's Willink, zebra mussels strain the water, making it clearer. Since they arrived in Lake Erie, for instance, water clarity has increased to 30 feet from six inches in some areas, allowing sunlight to penetrate farther, which benefits deep aquatic plants.

THE FIGHT: Once on the scene, zebra mussels are nearly impossible to eradicate. No biological controls are available, and chemicals poison other aquatic life. Because the mussels spread into new waters through boating, fishing, and scuba diving, conservationists are teaching recreationists to remove ones attached to boat hulls and equipment.

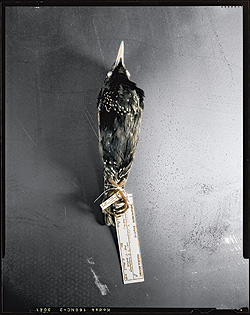

NAME: European starling (Sturnus vulgaris)

NAME: European starling (Sturnus vulgaris)

ORIGIN: Europe

DATE INTRODUCED: 1890

HOW IT GOT HERE: A literary man's whim

Blame the Bard. In 1890, a literature-loving pharmacist set free 60 European starlings in New York's Central Park, part of his plan to introduce all the birds of Shakespeare to American shores; since then these birds with glossy black iridescent feathers have spread coast to coast and now number around 200 million. (Paradoxically, they are mentioned only once in Shakespeare's works, in Henry IV, Part I.) Moving in large flocks, the starlings bully native birds, destroy crops, and possibly spread diseases, such as the fungal lung ailment histoplasmosis and Newcastle disease, which kills poultry. "They're aggressive pests," says the Field's Stotz. "They form large winter roosts; their droppings can befoul humans; and, most serious, they keep bluebirds, chickadees, tree swallows, and other holenesters from accessing nesting sites."

THE FIGHT: Starlings have proved to be unstoppable. Instead, local conservationists have focused on saving the starling's victims, mainly bluebirds, by building artificial nest boxes with holes too tiny for starlings to enter.