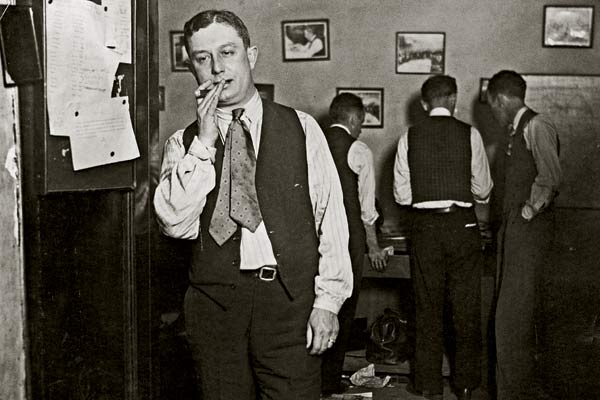

Though Jake Lingle, in the words of one colleague, “never mastered the art of writing,” he was a star of the Tribune newsroom thanks to his well-placed connections—including both Al Capone and Chicago’s chief of police.

Related:

THE LINGLE NETWORK »

The principal players in the 80-year-old murder mystery

PHOTO GALLERY »

Lingle’s life and death

On the Monday eight decades ago—June 9, 1930—when Chicago celebrated the opening of the new Board of Trade Building, the board’s officers planned a lavish dedication banquet at the Stevens Hotel, today’s Hilton Chicago. The city badly needed an occasion to cheer. The stock-market crash seven months before had punctured the economy. Gangsters virtually ran the town, raking in obscene sums when they weren’t gunning each other down on the street. The corrupt and clownish mayor, William “Big Bill” Thompson, swaggered around staging ludicrous stunts, when he was around at all.

The banquet that night brought together the city’s leading citizens, a who’s who of Chicago’s financial and political elite. But at least one name made a curious fit with the rich and powerful: Alfred “Jake” Lingle, a $65-a-week police reporter for the Chicago Daily Tribune.

Jake Lingle, however, was no ordinary reporter. He operated at the center of a network of friends and associates that may stand unmatched for its depth and width in the history of the grown-up city. His best friend was William Russell, the chief of police, yet Lingle talked regularly with Al Capone and other gangsters, conversations that produced countless scoops for the Tribune. He hobnobbed with Governor Louis Emmerson and collected tips on investments from Arthur Cutten, the millionaire Chicago trader. Politicians, prosecutors, judges, cops, and athletes all offered confidences to the 38-year-old reporter, but his network stretched far beyond the well connected. Years later, Levering Cartwright, a Tribune colleague, recalled being sent with Lingle on an assignment to Chinatown. “He knew every rat hole down there,” Cartwright said. “We’d go [into] the cellar and there’d be Chinamen playing dominoes or whatever it was, he knew them by their first names. A truck would come along with a Racing Form, and he knew the driver and would get a copy.”

But on that Chicago evening in 1930, Jake Lingle didn’t join the 2,450 bigwigs who dined on filet of Colorado mountain trout, saute meunière, in the grand ballroom at the Stevens, while listening to speakers toast the new LaSalle Street temple of capitalism and decry the “parlor socialists” undermining the country. Earlier that day, as the reporter ambled through a pedestrian tunnel at Michigan Avenue and Randolph Street, a tall young man had walked up and fired a fatal shot into the back of Jake Lingle’s head.

* * *

The murder of Jake Lingle, which had all the markings of a mob hit, set off an impassioned outcry in Chicago and across the country. It was one thing when the mobsters shot up each other, but now they had taken out a man “whose business was to expose the work of the killers,” as the Tribune put it. “People started to think it could happen to anyone,” says Tim Samuelson, the cultural historian for the city of Chicago. The furious city “went berserk,” as the investigative reporter Edward Dean Sullivan wrote at the time. Preachers, politicians, businessmen, editorialists, civic groups—all rose up and demanded action against the underworld.

And then, within a week or so, the slow drip of rumor broke into a torrent of news—Lingle was corrupt to his core. The exact levers of his graft remain unclear to this day, but it’s likely he acted as a middleman among mobsters, cops, and politicians, brokering deals to allow illegal operations—speakeasies, gambling joints, dog tracks—to operate freely. Astonishingly, no one at the Tribune had called him out for being crooked, even though he lived and spent extravagantly on his lowly newsman’s salary, and even though he paraded around wearing a diamond-studded belt buckle, a gift from Capone himself.

The story of Jake Lingle remains one of Chicago’s nagging murder mysteries, retold in books, a movie, episodes of The Untouchables, and countless newspaper and magazine articles. The case offers a vivid window on a particularly raw moment in Chicago’s past, but the Lingle saga also echoes into our era, where it seems that almost every day brings a new revelation of wrongdoing by people in positions of trust. Looking through the old newspaper accounts of the murder and its aftermath, watching Lingle turn from heroic victim to conniving scoundrel, it’s hard not to think of regular Chicagoans feeling their outrage once again sink to resignation. Today, a number of observers (myself included) suspect that that sense of resignation—that hopeless shrug in the face of the Lingle revelations and other public betrayals—persists into our own time and accounts in part for the viral corruption that continues to plague this city and state.

* * *

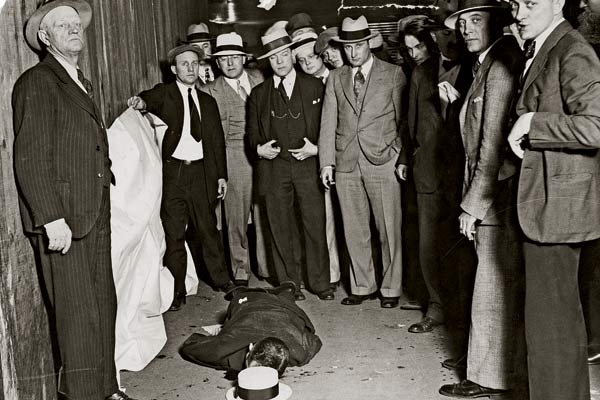

Photograph: Chicago Tribune photo

Camera-conscious onlookers gather around Lingle’s prostrate corpse at the scene of the murder.

Related:

THE LINGLE NETWORK »

The principal players in the 80-year-old murder mystery

PHOTO GALLERY »

Lingle’s life and death

For the Tribune’s imperious editor and publisher, Colonel Robert R. McCormick, the Lingle murder remained a lifelong embarrassment and concern. References to the case show up over and over again in McCormick’s personal papers, and even 17 years after a small-time triggerman had been convicted of the crime, top editors at the Tribune were tracking down yet another fresh lead on what had actually happened. Just six months before he died in 1955, the Colonel devoted one of his weekly speeches on WGN radio to the case.

A remote, driven autocrat—perhaps a foreseeable personality trait when your domineering mother unabashedly favors you alcoholic, manic-depressive older brother—McCormick blustered with overcooked opinions and half-baked dogma, but he believed fervently that newspapers had a mission. “Whenever asked what the most important purpose of a paper was, he would say to fight corruption,” says Richard Norton Smith, author of the 1997 biography The Colonel. “That’s why the Lingle thing was so painful.” Though Lingle had worked for the Tribune for 18 years, the Colonel knew nothing of the reporter’s dishonesty, and the boss and his employee had probably never met. (Tribune Company has owned Chicago magazine since 2002.)

They came from different worlds. McCormick belonged to Chicago royalty, descended from prominent families in manufacturing and journalism. Jake Lingle grew up in the “Valley” neighborhood on the West Side, south of Roosevelt Road, west of Halsted Street—in those days, an impoverished Irish area that produced soldiers and officers in the city’s early gangs. Though he told Tribune colleagues that his father was a successful businessman, Lingle came from a hardscrabble family that broke apart. He left school after eighth grade, worked in a warehouse, and landed a job at about age 20 as an office boy at the Tribune, reportedly on the recommendation of a West Side political boss. Even as a boy, Lingle had been a cop buff, and his Tribune editors quickly recognized his streetwise connections and made him a reporter.

In all his years with the paper, however, his byline appeared only a handful of times. “Lingle had never mastered the art of writing,” said John Boettiger, a Tribune reporter who became part of the murder investigation and wrote a 1931 book on the case. Lingle was a so-called legman—he’d phone in or recite the facts to another reporter who would then write the story.

Early on—by one account, when he was playing semipro baseball—Lingle met the man who would propel his career, an ambitious police officer named William Russell. The two became inseparable, sharing everything from golf dates to investments. “Jake’s like a son to me,” Russell later said. Through Russell, Lingle joined the insider fraternity of Chicago’s cops and became such a player in the affairs of the department that he was widely known as the “unofficial Chief of Police.” Mayor Thompson named Russell police commissioner in 1928, and some observers thought Lingle had a hand in the appointment. The mayor—who feuded bitterly with the Tribune—hoped the paper would mute its criticism if he promoted the star police reporter’s best friend. McCormick later scoffed at the idea that deals were made.

Using his street savvy and connections, Lingle also worked his way into the spheres of the city’s gang leaders, most notably the ruthless but irrepressible kingpin, Alphonse Capone. “He loved reporters and they loved him,” says the Chicago writer Jonathan Eig, whose book on the prosecution of Capone comes out next spring. Lingle became one of the mobster’s favorites. They had probably known each other almost since Capone arrived as a mob enforcer from Brooklyn, and they stayed in close touch as Capone moved up and consolidated his power. Lingle phoned in stories from Capone’s lavish compound in Miami Beach, and he visited the mobster while he served a short term in Philadelphia for gun possession.

Throughout Prohibition in Chicago, an assortment of gangs with fluctuating alliances fought over revenues from booze, prostitution, gambling, and labor racketeering. By the late twenties, the gang warfare had basically settled around two camps—Capone’s group, which controlled the South and West sides, and a North Side gang under the sway of George “Bugs” Moran. Lingle would have known Moran and dealt with him, but Bugs lacked Capone’s flamboyance—and it seems Lingle never warmed to him.

In any case, the eight or so Chicago newspapers competed with showy and sometimes lurid coverage of the leading players and the mayhem. “There was a point where people looked at [gang activity] as the exploits of modern cowboys, and the press was a lot of that,” says the historian Tim Samuelson. Lingle kept the Tribune in the game by bringing in stories from a long roster of mobsters. One Tribune editor, J. Loy Maloney, later described how Lingle once tipped the paper to hide some photographers near 15th Street across from a building with a police court. At the appointed time, three hoodlums emerged and two went down in a shower of gangland bullets, an attack captured on film by the Tribune. “Lingle was the quintessential guy who got around and had connections,” says Samuelson. “That’s how the Tribune tried to buffer the story [later on]—he needed the connections to do his job.”

* * *

From the distance of 80 years, it’s hard to get a focus on Lingle’s personality. His colleagues at the Tribune don’t seem to have known him well. Though journalism was hardly a gentleman’s trade, a growing number of the editors and reporters at the patrician Tribune had college degrees. Lingle probably stood out with his minimal education and nonexistent writing credentials. Perhaps in compensation, he presented himself well—“always newly tailored, manicured, barbered, shined and polished,” as one Tribune reporter put it.

Boettiger, author of the 1931 book, wrote that Lingle had “a blistering tongue and blunt, contemptuous way of dealing with people he disliked.” Another reporter, Walter Trohan, recalled that Lingle once tried to get him fired for lightly questioning his ethics. Other journalists remembered Lingle more fondly, but even his closest acquaintances wondered how this barely literate police reporter could end up mingling with the rich and powerful stars of Chicago’s establishment. His secret may have been his skillful assumption of a role: Lingle had a talent for playing the slightly mysterious, slightly elusive insider—dropping hints, flashing a cryptic smile. People enjoyed him as a unique Chicago character, Boettiger said. There’s evidence that the role came at a price: An ulcer tortured Lingle for years.

Nothing, however, explains the blindness of his colleagues and bosses to the strong evidence that Lingle had a racket going on. After reports of his finances came out in the weeks following his murder, his editor at the Tribune wrote a long, embarrassing front-page rationalization for the paper’s failure to spot trouble. (“The head of a family does not customarily go about investigating evil reports of the members of his flock,” wrote the paper’s city editor, Robert M. Lee.) But Lingle openly lived like a lord. With his wife and two young children planted in a house on the West Side, he stayed in a room on the 27th floor of the Stevens Hotel, one of the fanciest in Chicago at the time. He bought and furnished a weekend house in Long Beach, Indiana, and he took long vacations in Cuba. Sometimes he traveled around town in a chauffeured Lincoln, and he enjoyed peeling bills off a fat wad of money. He made, and lost, a small fortune investing in the Simmons bed company as the stock market soared and then crashed. And he had a terrible addiction to horse racing, often betting up to $1,000 on a horse. “Truly, he was a gambling fool,” recalled his colleague Fred D. Pasley.

Lingle explained his curious wealth with vague remarks about inheriting money from his father and his uncle. No one at the Tribune bothered to check whether Lingle was lying (he was) until later, even as Lingle kept up his warm association with Capone, who was known to lavish money and gifts on those he favored (and those whose favors he sought). A day after the murder, in an approving summation of Lingle’s insider connections, the Tribune wrote, “A belt buckle which Lingle wore, which was studded with what appeared to be diamonds, roused interest, and Jake used to laugh good naturedly at rumors it was a present from Capone.” The gang king later acknowledged giving Lingle the buckle. “He was my friend,” Capone explained.

* * *

Photograph: Chicago Tribune photo

A crowd throngs the entrance to the pedestrian tunnel where the crime occurred.

Related:

THE LINGLE NETWORK »

The principal players in the 80-year-old murder mystery

PHOTO GALLERY »

Lingle’s life and death

Jake Lingle’s charmed life ended at about 1:20 in the afternoon as he walked through a busy passageway under Michigan Avenue on his way to catch a train to Washington Park racetrack, a favorite haunt. With the single shot to his head, he fell forward, his cigar still clutched in his teeth, the Racing Form gripped in his hand—a death scene that writers thrilled to recount. Dozens of people were close by when it happened, and witnesses saw the presumed shooter flee up a stairway. He disappeared into the crowds west of Michigan Avenue.

Colonel McCormick got word by phone and hurried to the newsroom, where he announced a $25,000 reward for information leading to the arrest and conviction of the killer. Like everyone else, McCormick at first assumed the murder came as a reprisal or a warning because of Lingle’s pressing coverage of gang activities. In an editorial that showcased the Colonel’s martial infatuation, the paper declared war on the gangs. “The Tribune accepts this challenge. It is war. There will be casualties, but that is to be expected, it being war.”

On June 12th, thousands poured out for Lingle’s funeral, one of the largest Chicago had ever seen, and dignitaries filled the pews of Our Lady of Sorrows church at 3121 West Jackson Boulevard. A huge procession filed out for the burial in Mount Carmel Cemetery. The day before, McCormick had summoned his fellow Chicago publishers to a meeting, and in a joint statement they agreed to set aside ancient rivalries and cooperate in cleaning up the gangs “and any other public viciousness, wherever it may appear.” The dangled rewards soon totaled $55,000. Newspapers across the country published passionate editorials demanding that Chicago respond to this attack on the press. The clergy weighed in. “There never was a time in the history of Chicago when we needed the moral support and the backing of the decent people as we do today,” pronounced the Reverend Howard R. Brinker, president of the local Episcopal clergy’s organization. Coming just 16 months after the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre, the Lingle killing helped anchor Chicago’s reputation for being out of control.

Panicked into action by the public outcry, the police arrested 664 people in one 24-hour dragnet, and John Stege, the chief of detectives, announced confidently that the gang leaders had fled the city. “We shall see whether they dare come back to face our squads of police marksmen,” Stege said. Speakeasies and gambling joints shut down around the city (and reopened after the heat cooled).

In one of the moves that looks particularly odd by today’s standards, Colonel McCormick persuaded the state’s attorney to hire Charles Rathbun, a lawyer from the Tribune’s law firm, to take charge of the investigation. The paper picked up his fee and expenses, and the Colonel peppered him with notes of advice and observation. What’s more, John Boettiger, the Tribune reporter, joined the investigative team, and for months he worked side by side with the authorities. The potential for conflicts, cover-ups, and insider advantages was obvious, but when Herman Black, the publisher of the rival Chicago American challenged the arrangement, McCormick shot back, “Mr. Black, you have not been in Chicago very long. . . . [otherwise] you would know that the Tribune cannot be under suspicion. It is a preposterous thing even to discuss.”

(The stunning arrogance of the Colonel’s statement is perhaps softened by the fact that he believed it to be true. “The idea of the newspaper’s responsibility was in his blood,” says Richard Norton Smith, his biographer. “He felt it through his grandfather [Joseph Medill, a celebrated early editor]—his family’s role and its obligation to the greatest city in the world.”)

Behind the scenes, questions about Lingle’s integrity had started to float through newsrooms and boardrooms. A note in McCormick’s personal papers indicates that a colleague had warned him even before the funeral that rumors were circulating. On Monday, June 16th, a week after the murder, the Tribune published a bland, unbylined story saying the search for a motive had led to an investigation of Lingle’s finances. Later that day William Russell resigned as police commissioner, complaining that he had endured “nine hundred million tons of pressure”—presumably a reference to the mounting criticism of his friendship with Lingle and his failure to control the city’s lawlessness. Officials were already closing in on information that Russell shared at least one investment account with Lingle.

Rathbun released details of Lingle’s finances at the end of June. As Boettiger put it in his book, “[T]he completed picture of the mad, frenzied finances of Lingle . . . show him a plunger at the races, an unschooled speculator in the market, a borrower of large sums, and the recipient of an income which was in great part a baffling mystery.” The $65-a-week reporter had run through tens of thousands of dollars in the last two years, frequently making cash deposits of as much as $2,500. His “loans” came from assorted politicians, gamblers, and mobsters, and while some were repaid, according to the investigating report, many were not.

To this day, the source of the money remains a mystery, though several rather obvious explanations have been proposed. Most students of the matter assume that Lingle used his close connections to the upper echelons of the police department to arrange—for a fee—clear sailing for specific illicit operations. None of this was ever confirmed, but, for example, reports circulated that Capone paid Lingle $100,000 to assure that the gangster’s illegal dog tracks weren’t raided. Other observers assume that Lingle picked up additional cash by greasing promotions for ambitious cops willing to pay for the service. Whatever the sources, Lingle had apparently been at it for years, even before Capone was on the scene. Fred D. Pasley remembered Lingle coming back from a 1921 trip to Cuba with “literally a treasure trove of gifts,” including smuggled egret feathers, “coveted by women for hats.”

* * *

Within days of the murder, a St. Louis reporter appeared on the scene and wrote a series of articles suggesting that reporters and editors all over Chicago were on the take. “Only the dumb wits in the newspaper game in Chicago are without a racket,” one unnamed newspaper executive was quoted as saying. “I’m not exactly money hungry, but what’s the use of living like a tramp when the filthy lucre is being passed out like rain checks at the ball park.” By now, the city’s newspapers had abandoned the détente that had flowered after the slaying, and they took turns lobbing shots at each other’s integrity. Capone himself contributed to the bloodletting by asserting in an interview that he had “plenty” of newsmen on his payroll.

The smears were too much for Colonel McCormick. Furious, he ordered an internal investigation of the staff, detailing a trusted aide, Maxwell D. Corpening, a former polo instructor, to handle much of the work. Corpening found nothing inappropriate, but his cluelessness about journalism made him a newsroom laughing-stock. Several years later, assigned to do some simple reporting, the overmatched polo instructor handed in pages plagiarized from the Encyclopedia Britannica. “At least it proves the son of a bitch can read,” remarked Robert M. Lee, the Tribune’s city editor.

The Lingle affair unfolded just at the tail end of the swashbuckling era of Chicago newspapers celebrated in The Front Page, and some commentators have argued that graft pervaded the city’s journalism. “The profession was trying to get its act together in that era,” says James L. Baughman, who teaches the history of journalism at the University of Wisconsin. Publishers were writing ethics codes, and universities were founding graduate schools for journalists. “But big-city markets like Chicago made their own rules,” Baughman adds. Still, it was wrong to take kickbacks, and everybody knew it—witness the eagerness with which the papers exposed boodling by rival reporters. At the Tribune, rumors circled around Lee, the editor closest to Lingle, but nothing serious ever came out. No other Tribune reporter was implicated in wrongdoing at the time, and McCormick’s fury at the Lingle revelations suggests the integrity he expected from his employees.

It’s worth pointing out that in another sphere of journalism ethics, the Colonel’s record is much spottier: He wholeheartedly let his biases influence news coverage. “McCormick was a transitional figure in that he was very partisan,” says Baughman. “But that’s one thing, and it’s another thing to be on the take.”

* * *

Photograph: Chicago Tribune photo

Lingle’s funeral parade proceeds past Our Lady of Sorrows on West Jackson Boulevard.

Related:

THE LINGLE NETWORK »

The principal players in the 80-year-old murder mystery

PHOTO GALLERY »

Lingle’s life and death

The murder investigation zigzagged along through the summer and fall, with little success. Word had reached Charles Rathbun and his investigators that Lingle might have been killed by the North Side gang in return for his failure to protect a swanky, illegal gambling establishment, the Sheridan Wave Tournament Club. On Waveland Avenue, a few blocks east of Wrigley Field, the Sheridan Wave sounds like something out of a James Bond movie, according to contemporary descriptions—players in evening dress, free drinks and food, admittance allowed only to those known by the doormen. The club brought a steady, hefty stream of revenue to Bugs Moran and his hoods. The cops closed it in 1928; the place later reopened, then got raided again in 1929. The proprietors, including Julian “Potatoes” Kaufman, planned to open yet again, and, by some accounts, Lingle tried to hit them up for a fat fee or a cut of the profits in return for clearing the way. When they balked, Lingle vowed to arrange another raid. The Sheridan Wave never did start up again—opening night was scheduled for June 9th, the day Lingle was shot.

With rumors connecting Lingle to the club, the police arrested a Moran lackey named Jack Zuta, who was thought to be the brains behind the Sheridan Wave. In much of the contemporary journalism about the underworld, the writers can’t hide a smirking, boyish admiration for the mobsters. Not so with Zuta. It was bad enough that he “made his living out of women’s shame,” as Boettiger put it. He was also, by assorted accounts, a sniveling toady and a coward—though apparently his cowardice had some justification. After picking Zuta up, the police held him at a detective bureau at State and 11th streets, Capone territory. Nothing came of the interrogation, and when the cops released him, he begged for a police ride to the safety of the North Side. A cop was ferrying him up State Street in the Loop when a blue sedan pulled alongside, and a gunman let fly with a volley of shots that “sent three or four hundred startled citizens scurrying for cover in doorways, in alleys, behind lamp posts and refuse boxes,” the Tribune reported. A stray bullet killed a streetcar operator, the father of three children.

Zuta survived and fled to Wisconsin, hiding out at a resort near Delafield. A month later, as he was dropping nickels into a mechanical piano at the resort dance hall, five gunmen strode in and shot him to death. The murder was never solved, and some investigators thought Zuta had been silenced because of a role in the Lingle killing.

Zuta didn’t shuffle off, however, without leaving a parting gift. An obsessive packrat, as one judge described him, Zuta kept meticulous records, and investigators found a trove of documents connecting him to prominent judges, politicians, cops, and legislators. As Boettiger put it, “Chicago enjoyed a nine day sensation. Public officials came tumbling into the offices of the Lingle investigators, explaining how their names came [up] in the Zuta papers, why they took Zuta’s money, and how innocent they all were.”

* * *

As the investigation dragged on, Capone himself offered to help search for Lingle’s killer, and the gangster—perhaps playing out a ruse—held several secret, fruitless meetings with a representative of Charles Rathbun. Finally the authorities got a break. An informant heard that a mug going by the name Buster had shot Lingle and that he was still in Chicago. Using telephone wiretaps, the investigators traced the suspect to an apartment hotel at 4827 South Lake Park Avenue in Hyde Park. After an all-night stakeout, the cops arrested him on December 21st.

Buster turned out to be Leo V. Brothers, a small-time hood from St. Louis, where he had belonged to a gang called Egan’s Rats. At 31, Brothers was tall, with wavy blond hair and a long record, including a murder charge in St. Louis. For 17 days, Rathbun and his team held Brothers in secret and incommunicado at the Congress Hotel while questioning him about the Lingle assassination. Years later, Brothers claimed his treatment had been so brutal that he had overheard Boettiger tell a detective, “Why, if this man is freed, he will own the Tribune.” The investigators assumed someone had hired Brothers for the killing, but who? Brothers denied everything with a stoicism he kept up throughout the case.

By the time the trial started in March 1931, several rival Chicago papers—particularly the Hearst-owned Herald and Examiner—charged that the Tribune was railroading Brothers simply to clean up the Lingle affair. For appearances’ sake, Rathbun stepped aside as lead prosecutor in favor of the assistant state’s attorney C. Wayland Brooks (who later rode the Tribune’s backing to a U.S. Senate seat). In court, a defense lawyer for Brothers took up the conspiracy charge. “Find the motive of this prosecution,” thundered Louis Piquett. “Is it a prosecution by the state’s attorney or by the Chicago Tribune? . . . This is the most gigantic frame-up since the crucifixion of Christ!”

The state didn’t have to show a motive, however—it sufficed to prove that Brothers killed Lingle. The prosecution’s case rested solely on eyewitnesses, seven individuals who took the stand and identified Brothers as the man seen fleeing the scene of the murder. The defense responded with seven who said he wasn’t. Brothers himself never testified. The jury deliberated for 27 hours before returning what was clearly a compromise verdict—guilty of murder, but with the minimum sentence, 14 years. Brothers famously said afterward, “I can do that standing on my head.” The outcome no doubt disappointed the prosecution and the Tribune, but the verdict represented a landmark of sorts: After more than 500 gang murders in Chicago in the last decade, this marked the first time the authorities had brought in a conviction.

* * *

Much of Chicago was not persuaded. Rival papers inveighed against the verdict, and even Lingle’s mother wrote to Brothers in prison, saying she believed in his innocence. But the state supreme court upheld the verdict, and at the Tribune, McCormick remained certain that the killer had been found, ignoring a touching letter from Brothers’s mother asking for the Colonel’s help in freeing her son. (“Would a mother[’]s plea induce you to release my son so my few remaining years can be spent with him[?] You can do it. You know you can.”) Brothers served nine years and died in 1950, always insisting he was innocent.

The conviction did nothing to explain who ordered Lingle’s murder, however, and the mystery persists to this day. The two main schools of thought parallel the gang warfare of the time. One holds with the Sheridan Wave theory and argues that Lingle fatally annoyed Bugs Moran and his henchmen. By this analysis, Jack Zuta arranged the hit. As one Capone biographer, Laurence Bergreen, puts it, “From Moran’s point of view, the murder of Jake Lingle was the perfect crime, for Moran knew that the blame would fall on Capone.”

The rival explanation points the finger at Capone, who, by this line of reasoning, had decided that Lingle had double-crossed him, either by failing to deliver on promised protection or by cozying up to the North Side gang. Another Capone biographer, John Kobler, provides evidence for this view in citing a letter written by Mike de Pike Heitler, an estranged Capone “whoremaster.” Heitler had left the letter with his daughter with instructions to deliver it to an investigator in the event something happened to him. His body was found in a burned-out car in late April 1931. In the letter, Heitler claimed that eight Capone gangsters had conspired to murder Lingle, and Heitler quoted Capone as saying, “Jake is going to get his.”

Colonel McCormick blamed Capone, but on slightly different logic. The feds were starting to build the tax case that would eventually send Capone to prison in 1931, and they hoped that Lingle, given his warm association with the mobster, might provide some helpful details. (Federal agents did talk to McCormick about Lingle, but—contrary to several later accounts—only after the murder.)

Jonathan Eig, author of the forthcoming Get Capone, doubts that the mobster ordered the hit. “It doesn’t make sense,” Eig argues. “Capone had much bigger problems at that point. The feds were breathing down his neck. He knew his phones were tapped. He was lawyered up.” The Heitler letter was suspicious from the start—Heitler was illiterate, and the woman to whom he supposedly dictated it could barely read and write. As for the tax case, “The IRS investigation was already well under way, and Lingle wasn’t a key source,” Eig says. “There were lots of people who knew more and talked to the agents, and no one got hurt.” Besides, he adds, “The Lingle hit was anything but a Capone-style hit. Too many witnesses.”

So does that point the finger at Bugs Moran and his boys? That’s Eig’s best guess.

* * *

Photograph: Chicago Tribune photo

Related:

THE LINGLE NETWORK »

The principal players in the 80-year-old murder mystery

PHOTO GALLERY »

Lingle’s life and death

In any case, Colonel McCormick came to believe that the Tribune-declared war on the gangs contributed to the eventual downfall of Capone and struck a deathblow at the underworld. Boettiger’s notions were never far from his boss’s, and the writer put it this way at the conclusion of his book: “[I]n years hence [the murder of Lingle], the crime of a century, may be reckoned as the starting place from which the fall of Chicago gangdom shall date.”

Of course, Chicago gangdom didn’t fall. Capone and his top aides went to prison, and Prohibition killed the booze trade, but the underworld regrouped and thrived, continuing its alliance with the city’s political class—a disheartening partnership that stretched for at least another half century. “Machine politics were set up to protect vice and crime,” says Robert M. Lombardo, an assistant professor of criminal justice at Loyola University. A former police detective, Lombardo concedes that the Chicago Outfit is in decline today, but he points out that local authorities didn’t strike the mortal blow—the suburbs did. “Those old neighborhoods, the racket subcultures—they’re gone,” Lombardo says.

Meantime, the so-called culture of corruption in Chicago and Illinois politics continues to offer up a steady effluence of malfeasant public officials. “What is it in the electorate that finds that acceptable?” asks Richard Norton Smith, who has firsthand knowledge of Illinois, having served as the founding director of the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum in Springfield. “There’s an element of resignation bordering on cynicism,” he adds.

Patrick Collins, the former federal prosecutor who chaired the Illinois Reform Commission appointed in the aftermath of the Blagojevich debacle, says he has heard various theories to explain the persistent corruption in Chicago—for example, that the city’s tough immigrants embedded the custom of scuffling and cutting corners to get ahead; that crime and corruption has become a spectator sport, an entertainment that doesn’t demand change. In general, Collins concedes, “At a citizen level, for some reason, [the imperative for honesty in government] doesn’t take hold—there’s a resistance, a built-in skepticism.”

Jonathan Eig suggests that the Lingle murder came as a climax to a critical period of Chicago history. “It seems to me there was a constant battle going on in the twenties in Chicago to try to figure out just where the city stood on immorality, because the reformers came and went, Mayor Thompson came and went.” The newspapers by then had a national imprint, so Chicago’s reputation carried across the country. “I think [Lingle’s murder] became a dramatic call—an ultimate moment to get on the right side of morality, show the country that Chicago can clean itself up.” In that scenario, “Lingle is seen as a symbol of democracy.”

And then, Chicago came to know him.

* * *

In private ways, the Lingle murder took its toll on the principals. In The Colonel, Richard Norton Smith writes memorably that McCormick’s sense of betrayal by his employee led him to become even more suspicious and reclusive. “His office came to resemble the jail cell in which Leo Brothers served his sentence, but with one critical exception,” writes Smith. “When his time was up, Lingle’s convicted killer walked out of prison for good. McCormick remained incarcerated by his own wish for as long as he lived.”

John Boettiger parlayed his hard-earned favor with the Colonel into better assignments, and soon he was covering the 1932 presidential campaign. He came to know Franklin D. Roosevelt’s daughter, Anna. Though both Boettiger and Anna were married to others, they fell in love and, after divorces, married. Boettiger left the Tribune in 1934 but kept in touch with the Colonel, writing him as late as 1947 to remark on a lingering issue in the Lingle case. Over the years, Boettiger failed at assorted journalistic and business ventures; eventually the marriage to Anna failed, too. Battered by depression and shame, he took his own life in 1950.

And what of Jake Lingle’s surviving family? The most poignant story in the aftermath of the killing describes the scene at Lingle’s mother-in-law’s house on the West Side, where Jake’s wife, Helen, and their two children were spending a few days before moving to the summer home in Indiana. “Trunks stood ready packed in the hall, and the final articles were ready to be tucked into the traveling bags,” the Tribune reported. “Down on the front lawn, Buddy and Pansy, as the children are called, romped for the last time with their playmates.” Upstairs, where Helen Lingle had just heard the news, she cried, “If only he’d lived a little while. If only I could have seen him.”

The family stayed in Chicago. Helen Lingle never remarried, and the son, Alfred Jr., raised a family here himself, working as a salesman. Both he and Helen are dead now, but I talked to one of his sons—a grandson of Jake—Kevin Lingle, a Chicago actor. He’s in his mid-40s, a good-looking, brown-haired man with piercing eyes. He says family mythology holds that he looks like his grandfather. In fact, he says, “I’d like to play Jake in a movie.”

Still, Kevin is guarded about how the shadow of an infamous murder affected his family. His grandfather’s killing was rarely discussed in the family—he says he first learned of its significance watching TV, when Geraldo Rivera told the story as part of the buildup to the opening of Capone’s vault in 1986. “It was quite a shocking thing,” Kevin recalls. Since then he has done some research, but he’s turned up little. As for that diamond-studded belt buckle—Kevin says it’s vanished somewhere in the past.