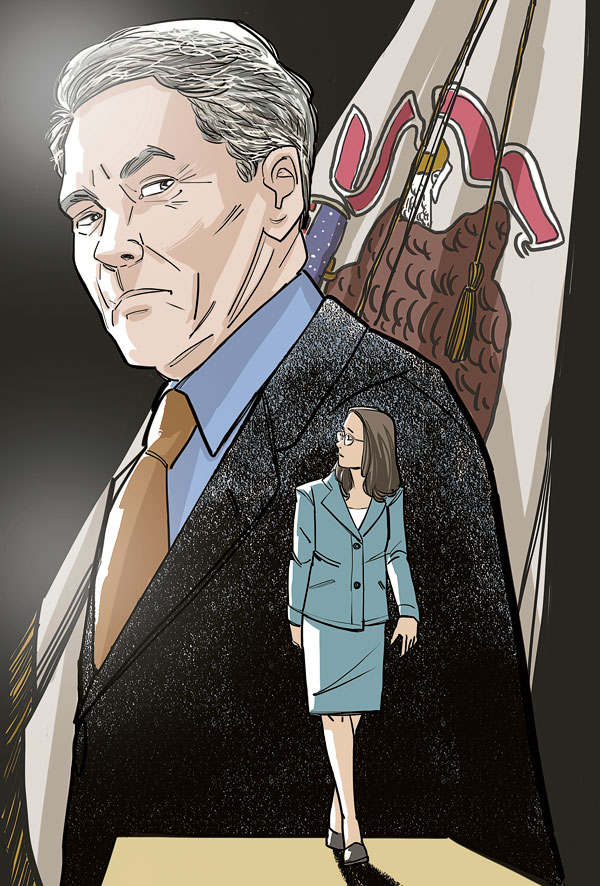

This summer, House speaker Michael Madigan dealt Governor Bruce Rauner one of the greatest political humiliations in Illinois history. The Wizard of West Lawn persuaded 10 Republicans to join the Democrats in overriding the governor’s veto of his budget—a budget that included a 32 percent tax increase and none of the labor reforms Rauner had demanded since the moment he was sworn in.

The result of this two-and-a-half-year standoff should have been no surprise. Rauner, who has devoted his life to accumulating money, was a political amateur getting pantsed by one of the greatest political tacticians who has ever operated under a capitol dome—a man who has devoted his life to accumulating power. It was like the scene in The Hustler when Fast Eddie Felson takes $12,000 off a bourbon-and-rose-scented aristocrat at the Kentucky Derby.

It’s rare to find a politician who doesn’t think he deserves a promotion. Every congressman fancies himself a senator; every senator, a president. But Madigan has sat in the entry-level Illinois House of Representatives since 1971, and for 32 of the last 34 years, he has been its speaker, making him the longest-serving legislative leader in American history. While his colleagues were plotting to move up, he was plotting to make the speakership—a position that others have used as a steppingstone to the U.S. Senate or the governor’s office—more powerful. In a career full of shrewd moves, that has been the shrewdest.

Madigan was Richard J. Daley’s water carrier in the House and may have aspired to succeed the Boss, but “in the post-Daley era, that wasn’t going to happen,” says Kent Redfield, a former legislative staffer and now a political science professor at the University of Illinois Springfield. “He saw the potential of building a power base outside Chicago politics.”

Emulating his mentor’s patronage politics, Madigan has built a staff that doubles as a campaign army for fellow legislators, which “really centralizes power in the hands of the speaker,” Redfield says.

A trim, fit 75, Madigan is still at the top of his game: His influence over Illinois politics rivals that of Daley or of 1960s House speaker and Secretary of State Paul Powell, the Gray Fox of Vienna, who amassed a $4.6 million fortune on a $30,000 salary. Nearly 20 years ago, Madigan installed his adopted daughter, Lisa, in the Illinois Senate, knifing an old ally named Bruce Farley in the process. (It was not only a generational move but a geographic one. The 13th Ward, of which Madigan is committeeman, is now about two-thirds Latino: An Irish-surnamed politician would have a better future on the white North Side.) After one term, Lisa moved up to attorney general. It was assumed that she would one day run for governor, carrying the Madigan name to a height her old man had never reached.

First, though, the old man had to quit. And he won’t.

“I feel strongly that the state would not be well served by having a governor and speaker of the House from the same family and have never planned to run for governor if that would be the case,” Lisa said in her 2013 announcement that she would not challenge Governor Pat Quinn in the Democratic primary.

Then, in September, it was Lisa who quit, rather than her old man. Faced with the prospect of turning into the Eternal General, she announced that she won’t seek a fifth term. Instead, she’s reportedly seeking greener pastures in private practice. As it turns out, Michael Madigan’s desire for power is more enduring than his daughter’s.

So why doesn’t the speaker step down? And what might finally persuade him to give up the office he has held for three-fifths of his life?

“I suspect at some point when you become that powerful in that small little area, it’s probably hard to turn off,” says former state representative Ron Sandack, a Downers Grove Republican who served in Madigan’s House from 2013 to 2016 and believes that the speaker loves the “rush” of legislative victories. “Bruce Rauner’s the executive, but when it comes to the legislative process, there’s only one guy.”

Redfield can imagine Madigan bowing out if Rauner is defeated for reelection next year, satisfied that he ended the political career of a governor who tried to challenge his power. On the other hand, Madigan may want to collaborate with a Democratic governor on redrawing the legislative maps after the 2020 census. (Madigan’s 2010 remap, which resulted in a gain of four congressional seats for the Democrats, “punched his ticket to the partisan Hall of Fame,” according to Politico.)

As for Lisa, she is only 51, so she can afford to wait eight years to run for office again. And she may be best served by sitting things out until her father leaves office. Rauner has spent millions running ads charging that “Mike Madigan will do anything to keep power, even take down Illinois.” The ads have so poisoned the family brand that Lisa is said to have feared a tough reelection race against former Miss America and Harvard Law School graduate Erika Harold. As master of the legislature, Madigan has to bear blame for $16 billion in unpaid bills and a bond rating one step above junk. In 2016, his Democrats lost four seats, even as Hillary Clinton won Illinois by 17 points.

“Some people who would love to take Madigan out might take it out on her,” Sandack speculates. “Michael Madigan is the least popular and most powerful politician in Illinois.”

There’s only room for one Madigan at the top of Illinois politics; until Michael Madigan dies or decides he can live without the speakership, it’s going to be him. Power is thicker than blood.