For most of his life, longtime Naperville resident Isaac Levendel had no idea what had happened to his mother, Sarah, after she disappeared from where they were living in rural France in 1944, when he was 7. They were both registered Jews under the Nazi-collaborating Vichy regime, so he assumed the worst. But it would be 46 years until Levendel felt ready to hunt for the details. His effort pulled at the heartstrings of one French bureaucrat, who admitted to him that Veterans’ Affairs had in its archives World War II–era records of Jews marked for arrest, including a card for his mother. But since they were racial records, they were illegal under French law and, therefore, did not officially exist, as Peter Hellman wrote in his 1994 Chicago story “The Long Goodbye.”

Veterans’ Affairs could not send Levendel an official copy of his mother’s card, no matter how much he wanted it, if it didn’t exist. But the bureaucrat, in a private act of kindness, sent him a copy of the card in a plain brown envelope without a return address, as if it were pornography.

Levendel learned that his mother had been sent by cattle car to Auschwitz, where, an eyewitness reported, she was killed in a gas chamber. Shortly after, the French newspaper Le Monde broke a story about the records and the French government’s erasure of its active role in the Holocaust. Levendel published his memoir in France in 1996 and in English three years later as Not the Germans Alone: A Son’s Search for the Truth of Vichy. He later wrote a book with journalist Bernard Weisz about how the French Mafia rounded up Jews for the Nazis.

Read the full story below.

The Long Goodbye

For decades a Naperville computer engineer was tormented by the disappearance of his mother in France during the Holocaust. His search for clues took him into the yellowing, secret archives of Nazi-occupied France — and shed light on a shameful chapter of French history.

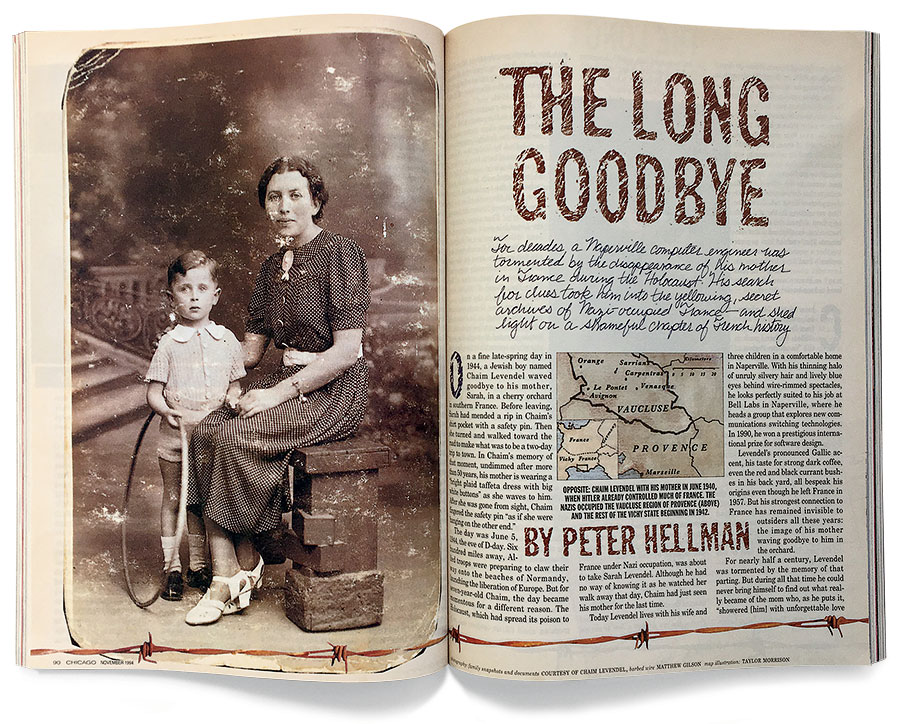

On a fine late-spring day in 1944, a Jewish boy named Chaim Levendel waved goodbye to his mother, Sarah, in a cherry orchard in southern France. Before leaving, Sarah had mended a rip in Chaim’s shirt packet with a safety pin. Then she turned and walked toward the road to make what was to be a two-day trip to town. In Chaim’s memory of that moment, undimmed after more than 50 years, his mother is wearing a “bright plaid taffeta dress with big white buttons” as she waves to him. After she was gone from sight, Chaim fingered the safety pin “as if she were hanging on the other end.”

The day was June 5, 1944, the eve of D-day. Six hundred miles away, Allied troops were preparing to claw their way onto the beaches of Normandy, launching the liberation of Europe. But for seven-year-old Chaim, the day became momentous for a different reason. The Holocaust, which had spread its poison to France under Nazi occupation, was about to take Sarah Levendel. Although he had no way of knowing it as he watched her walk away that day, Chaim had just seen his mother for the last time.

Today Levendel lives with his three children in a comfortable home in Naperville. With his thinning halo of unruly silvery hair and lively blue eyes behind wire-rimmed spectacles, he looks perfectly suited to his job at Bell Labs in Naperville, where he heads a group that explores new communications switching technologies. In 1990, he won a prestigious international prize for software design.

Levendel’s pronounced Gallic accent, his taste for strong dark coffee, even the red and black currant bushes in his back yard, all bespeak his origins even though he left France in 1957. But his strongest connection to France has remained invisible to outsiders all these years: the image of his mother waving goodbye to him in the orchard.

For nearly half a century, Levendel was tormented by the memory of that parting. But during all that time he could never bring himself to find out what really became of the mom who, as he puts it, “showered [him] with unforgettable love and care for eight years minus 22 days.”

Finally, in 1990, he found the strength to start looking for answers.

His quest — chronicled in a memoir to be published next year in France — took him from Naperville back to France more than a dozen times over the past four years. Despite the passage of time, he had little difficulty finding witnesses to his mother’s fate. But he encountered enormous problems in trying to gain access to the official French archives that documented the inglorious years of Vichy rule during the Nazi occupation. In the end, with help from at least one sympathetic bureaucrat, he obtained secret documents that enabled him to piece together a wrenching picture of his mother’s final days. In the process, Levendel unearthed truths that many in France would have preferred to keep buried forever.

Chaim’s father, Max Levendel, emigrated to France from Poland in 1930. Unskilled, he found work in the Vaucluse region of Provence as a farmhand and then as a house painter. He returned to Poland in 1935 intending to marry a cousin. But finding her already taken, he married her sister, Sarah, and took her back to the Vaucluse to live in the village of Le Pontet. In 1936, the year of Chaim’s birth, the newlyweds opened a dry-goods shop. Sarah oversaw it while Max traveled to local outdoor markets to sell merchandise. In their version of the French dream, they saved enough to buy a used car — a stately British Talbot.

Sarah took pride in the shop, but she positively doted on Chaim, a bright, mischievous boy with a head full of blond curls. “She believed that the importance of her child was directly proportional to the hardship he caused you,” he says. Chaim did his part. There was the time he was dandied up all in white for a family photograph. While his mother dressed, he opened a container of black shoe polish and smeared it all over his white shoes and much else. Sarah was only briefly furious. Later, she’d tell friends “how clever” her son had been. “Her faith,” says Levendel, “was the source of my inner strength and confidence once I was alone.”

Chaim was three years old when Hitler crushed France in June 1940. His father, who by then had joined a Polish unit of the French army, was taken captive and remained a prisoner of war for the duration. The French legislature fled from Paris to Vichy and established a new government in the Unoccupied Zone. On French postage stamps, the graceful figure of Marianne, symbol of the republic, was replaced by that of Marshal Henri Philippe Pétain, hero of Verdun and elderly head of the new state. The Vichy regime quickly showed its eagerness to emulate Nazism. Its first racial law was enacted in early October 1940. Harsher even than its counterpart in Occupied France, the law defined a Jew as anyone with two Jewish grandparents (the 1935 Nuremberg definition required three). Vichy continued issuing racial editcts until three weeks before the liberation of Paris in August 1944.

The new racism visited the Levendels in the summer of 1941, when a town clerk came and inventorized the family’s possessions as required by Vichy law. Chaim still remembers his mother’s anger at this intrusion by “the little bureaucrat with his thick mustache and the traditional beret.” How could the wife of a soldier who had served France be treated so unfairly? That same summer, the Levendels were registered as Jews with the prefect of Avignon, who tallied 1,016 French-born and 458 foreign-born Jews in the district. In meticulously organized card files on both sides of the Vichy line, a total of 120,000 Jews were registered in the land.

Yet for a time, things remained relatively normal in Le Pontet. In school, Chaim excelled at math. As Pétain paraded through the town in a white convertible one day, the boy joined his schoolmates in singing at the top of his lungs, “Maréchal, nous voilá!”

The Germans occupied the Vichy state in November 1942. In the Vaucluse region where Le Pontet is situated, German presence was minimal, but racism intensified. In school, Chaim heard his former friends call him a “dirty Jew.” His mother now kept two buckets of water beside the bedroom window behind the shop, ready to pour on children who sneaked up to shout or scrawl hate slogans. Next door, the proprietor of the Sporting Bar was a known collaborator. Still, Sarah Levendel rejected the warnings of friends — especially those of another Polish-born family named the Steltzers, who lived in the nearby small city of Carpentras — to go into hiding in the countryside. “For my mom,” says Chaim, “the shop represented her independence.”

By the late spring of 1944, Sarah seemed to be winning her gamble despite the fact that Jews — especially those who were foreign born — were no longer safe from arrest in places like Le Pontet. Each morning, she’d fill an outdoor tub with water and let the sun warm it for Chaim’s noon bath, during which she’d tell him stories of the family’s excursions to the sea with the father Chaim only dimly remembered. Their automobile, stored in a garage for the first years of the war, had been sold. But the semblance of normal life for mother and son still seemed strong on a Sunday afternoon in May when they dressed up to attend the horse race at a nearby estate called Roberty.

Or perhaps, in the weeks before her disappearance, Sarah did have a dark premonition. Waking on those final mornings, Chaim remembers finding his mother at his bedside, silently watching over him.

Sarah registered as a Jew with the French police, as required by Vichy, for the third time on May 15, 1944. Allied bombers now regularly hit the area, even destroying a herd of cattle kept by the Germans near the Roberty racetrack. Still, a new round of arrests of Jews were carried out in the Vaucluse — and the news must have reached Sarah. At last, she acquiesced to the pleas of the Steltzers to join them in the countryside.

On a bright June morning, Sarah and her son went by bus to Carpentras, whose intimate 12th-century synagogue in the city square is the oldest still functioning in France. They took another bus to the sleepy hilltop village of Venasque, ten miles away. A teenage farm boy awaited them in a mule cart. Plodding along a cypress-bordered dirt road, the mule suddenly reared up. Shinnying up its back, the farm boy clamped his fingers into its nostrils, subduing it instantly with the force of his grip. That act instantly turned the teenager into Chaim’s hero.

Sarah and Chaim spent the night in an outbuilding on the farm and found the accommodations tolerable. In exchange for the farmer’s permission to stay there, she agreed to pick cherries at harvest time. After settling these matters, all that remained was for Sarah to return briefly to Le Pontet to pack and close up the store. She was to be back on the farm in two days. As she prepared to set out, Chaim decided he would rather stay behind with his new hero, the farm boy. The decision probably saved him from sharing his mother’s fate.

Two days passed, but Sarah Levendel did not return to the farm as she’d promised. Chaim didn’t know what had delayed her, but he felt sure he’d find her at home in Le Pontet. He was escorted there by 15-year-old Claire Steltzer, who was also hiding on the farm. They found the shop’s iron gate ajar and its shelves stripped of the buttons, thread, ribbons, and clothing that Chaim had loved to help his mother arrange. In the kitchen, at the rear of the store, he stared at the stove, where he’d always huddled on winter evenings while his mother read him his bedtime story. Inside the over was a pan containing a dried and charred omelet, made his mother’s way. Clearly, she’d been interrupted before she could eat it. The sight of that omelet pierced Chaim with loneliness.

As Chaim stood alone in the kitchen, neighbors whispered to Claire the news: Two men had pulled up in front of the shop in a large black Citroën. They’d dragged Sarah away as she wept and pleaded with them to let her go.

Claire took Chaim to her own family’s apartment in Carpentras, where her parents had returned from the farm. As Chaim waited in the living room he overheard arguing behind the closed door of the kitchen.

“I told her so,” wailed Claire’s mother hysterically in Yiddish.

“There’s nothing to do anymore,” said Claire in French. “The Germans have her now.”

Only then did Chaim weep. Claire walked with him on Carpentras’s narrow streets, trying to calm him down. At a toy store, she bought him a set of “osselets”: five aluminum “lamb bones.” The object of the game was to throw up one bone and catch it with one hand while picking up the four bones with the other hand. Claire persuaded Chaim to stop crying in exchange for the toy. “At that moment, I locked my wound inside me and stopped sharing my sadness with others for the next 46 years,” he says.

With Sarah’s arrest, the Steltzers decided that the Venasque farm was no longer a safe haven. They placed Chaim with another farm family, the Bres, who lived near the village of Sarrians. As only a child can do, Chaim quickly adapted to his new surroundings, becoming a farm boy in a large peasant family. The Bres couldn’t love him the way his mother had, but their warmth was real. His happiness among the Bres was punctured that August, when he discovered that he’d lost the safety pin that he calls “my last link to my mom.”

One day at war’s end, Chaim was staying in Carpentras with the Steltzers (all of whom had survived the war) when a small, reserved man in a uniform appeared. Chaim didn’t recognize the man as his own father. Putting his son on his knee, Max Levendel immediately began telling Chaim stories from the Bible. It was hardly a joyful reunion. Chaim longed for his mother, not this father who lacked the emotional tools to engage his son. Max couldn’t even bring himself to discuss what had happened to Sarah. The estrangement between father and son deepened when Max took up with a tall, stern woman named Ruth whose husband had died at Auschwitz-Birkenau and whom Max eventually married.

Rather than live at home with his father and Ruth, Chaim went to live with another peasant family, the Sourets. Their ramshackle house, two miles from Le Pontet, “stank like hell,” Levendel recalls fondly. The family members were illiterate, and Chaim quickly proved valuable to them because he was able to tally their weekly milk sales. The four Souret children were grown or nearly so. Madame Souret, a fat woman no longer allowed her husband to sleep with her. So Chaim, an undersized child, shared her bed. Madame Souret vowed with a wink to bathe “after Easter” but in the next breath claimed that “water wasn’t meant for cats or people to bathe in.”

The Sourets were suspicious of outsiders. “Try to be friends with a stranger, he’ll just dump on you,” claimed Madame Souret. Yet the whole family welcomed this skinny Jewish boy, and he doted on their warmth — as nurturing and as an uncritical as his mother’s had been, even though the Sourets could not have been more different from her. “It didn’t take long for me to become a Souret,” Levendel says, “dirty and stinking, warm and fun-loving, prejudiced but loyal, dishonest but sincere, simple and giving, just as they were.”

In the years that followed, Chaim earned top honors at a college in Nancy, and then moved to Israel in 1957 to study engineering, teach school, and live on a kibbutz. While visiting Belgium, he fell in love with a pretty blond, blue-eyed nursing student named Elsa, whom he eventually married. They settled back in Israel on a desert kibbutz and had two children there. In 1974 the family moved to Los Angeles, and Chaim earned a doctorate in computer science and engineering at the University of Southern California. They have lived in Naperville since 1976, and added a third child in 1980.

As a father, Levendel says that each time one of his children reached the age of seven, as he’d been when he lost his mother, “they seemed so vulnerable it scared me.” Yet he rarely spoke to his children about what happened to his mother. “It wasn’t part of our life,” says his 26-year-old daughter Noa. “But when my little brother Ilan turned seven, I felt, as the big sister, Oh, my God, he’s so tiny — yet that’s how old my father was when he was left all alone.”

Levendel now refers to his silence as his “40 years in the wilderness.” During that time, he never accepted that his mother had been killed by the Nazis. Instead, based on a conversation he overheard as a teenager, he believed that she had been driven mad with grief after being separated from her son and might be living in a French asylum. This hope even played out in a dream wherein Madame Souret took him to visit his mother at an asylum in the countryside, carrying with her a sweater she’d knitted for the old lady. In the final scene, Madame Souret took the boy back to Le Pontet, where his stepmother, Ruth, showed her “profound disapproval” at their visit to the asylum.

Levendel held on to that dream, even as he struggled for the strength to confront reality. It wasn’t only his mother’s fate that haunted him. He felt guilt at never having thanked the two farm families who had risked their lives by taking him in. He also feared they’d be angry that he had ignored them for so long. But by the time Levendel turned 50, he was becoming increasingly aware that precious time was passing. Finally gathering up his courage, he tracked down the aging Bres children to homes not far from the original family farm. Of the four children, three were still alive.

The Bres wept with pleasure at the return of their “Jacqui,” as the boy had been called in school. Back in Naperville, Levendel received a letter from Magali Bres. “Rather than feel betrayed by your long silence my family is in awe of your ability to find us again,” she wrote.

Reunion with the Bres, says Levendel, “gave me the strength to free myself from my long silence concerning my mother’s story.” He found more strength at the first Gathering of Hidden Children, held in New York City in 1991. After a lifetime of carrying a heavy burden alone, he found himself among more than 1,000 other adults who had been separated from their parents as children in Nazi-occupied Europe. “For the first time,” he explains, “I felt my isolation disappear.”

Long determined to hide from the truth, Levendel has obsessively sought it out for the past four years. His first step was to phone Serge Klarsfeld, the Paris-based French Nazi hunter and master historian of the Holocaust as it was carried out in France. Levendel told Klarsfeld, that he thought his mother might still be in an asylum somewhere in Provence. Possible but unlikely, thought Klarsfeld.

“Have you looked in the Memorial to the Jews Deported from France?” Klarsfeld asked. That book, written by Klarsfeld, is a massive directory of death containing the names of the nearly 80,000 Jews deported between 1942 and 1944, mostly from Drancy, outside Paris, to Auschwitz. Levendel had not consulted the Memorial.

Within the hour, Klarsfeld called back. Gently, he told Levendel that his mother’s name appeared in convoy 76, which left Drancy on June 30, 1944. Of about 1,150 Jews on that train, 47 were known to have survived Auschwitz. Sarah Levendel was not among them.

Discovering his mother’s name on a deportation list, despite its apparent finality, did not satisfy Levendel’s curiosity. Indeed, it only made him determined to flesh out exactly how, 24 days after he’d last seen her in the cherry orchard, his mother ended up in a cattle car bound for Auschwitz.

The first break came when he located Gaston Vernet, one of his childhood friends, who had lived on the street behind the Levendels. Vernet remembered well. The two men who had pulled up in front of the store that June day wore black leather jackets and spoke, said Vernet, “with an accent from the south of France.” In other words, they were Frenchmen, not Germans as Levendel had always believed. Nor were they police. When they tried to take her away, Sarah Levendel, who’d been at the stove making her omelet, had dashed out the rear door to Vernet’s house, where she was trapped. Telling them that her child was awaiting her, she begged to be released.

“Sirs, have you no hearts?” she implored.

“Yes, madame, but our hearts are made of steel.”

According to Vernet, the distraught woman tried to cut her wrists with a kitchen knife before it was wrested from her. The two men beat her on the floor before dragging her to their car and driving off.

Levendel learned what happened to his mother next thanks to a tip from the director of the archives of the Vaucluse, located within the massive former papalpalace in Avignon, The director mentioned a book called Memories of a Survivor, written by Estrea Asseo, a local woman who had been arrested on the same day as Levendel’s mother and had survived Auschwitz. Levendel found her name in the Avignon phone directory. A tiny, energetic woman born in Trieste, Asseo was 84 years old when Levendel visited her in her airy apartment a few blocks from the papal palace. The number tattooed to the underside of her wrist was still clearly visible.

All the Jews arrested in the Vaucluse that day, explained Asseo, had been delivered to a military jail in Avignon. Even after 45 years, she clearly remembered the woman in her cell from Le Pontet who had “cried for her little boy without respite.” At midnight, they were transferred in the private cars of French militiamen to the Saint Anne prison in Avignon. In Asseo’s group of four women, by her account, “one had passed out.” At that spot, in the copy of her memoir that Asseo gave Levendel, she wrote: “Your mother, Madame Levendel.” Two nights later, on June tenth, came another midnight transfer, this time by a train bound northward to the transit camp at Drancy. On June 30th, both women were loaded into the same cattle car for the five-day trip, without food or toilets, that ended at Auschwitz.

Much has been written about the horror of Auschwitz. The journey there may have been, in its own way, a greater horror: 100 people packed tightly, wilting in the stench and summer heat. There was no water. People died in place, and fights broke out among the living.

On the fifth day, they arrived at Auschwitz. It was July 5, 1944, one month after the goodbye in the cherry orchard. Still strong and healthy, Asseo was selected for slave labor. Sarah Levendel, ill and spiritually broken, was sent directly to the gas chamber. On that day, Chaim was at school in Sarrians, already a part of the Bres family. He’d not yet lost the safety pin that was his last connection to his mother.

It was surprisingly easy to find witnesses able to provide a detailed picture of Sarah Levendel’s final month. Gaining access to official documents touching on her fate in the French archives, however, proved far more difficult — though not because such documents didn’t exist. The French are avid record keepers. More than 100 prefectoral, regional, and specialized archives are engorged with documents, as are the vast National Archives in the heart of Paris. Like land and language, paperwork is considered to be part of French patrimony. Much of it is readily accessible. In the crowded reading room of the Vaucluse archives one summer day, for example, an American visitor noticed a woman studying an ancient tome.

“It’s a village notary’s record of business transactions dating from 1523,” she explained. She pointed to a record of the sale of a cow by one farmer to another.

That document was available for the asking, as are most others from across the centuries. Just don’t request documents from the Vichy years, 1940 to 1945. Even the most eminent scholars have a hard time obtaining them — and are sometimes turned down flat.

“This area is delicate, delicate, delicate,” Intoned Monsieur Ayez, head of the Vaucluse archives, as he considered Levendel’s request to see documents concerning measures against Jews in Vichy times. The French don’t like being reminded of their complicity in the Final Solution, particularly their arrest and delivery of Jews to the Germans, as happened in Le Pontet on D-day.

All kinds of skeletons are hung in the archival closet. Levendel, for example, had been advised by Ayez to read a history of the Vaucluse under Vichy written by a local dignitary named Aimé Autrand. The late author’s credentials were impeccable. He’d been appointed to a national committee that prepared the official history of wartime France. But when Levendel later was granted limited access to the Vaucluse archives, he discovered that Autrand himself, as a deputy prefect, had been responsible for arresting local Jews.

Levendel’s search of the Vaucluse archives revealed little about his mother beyond her registration as a Jew as ordered by Vichy. He had better Iuck with the Veterans’ Affairs archives in Paris — a source Klarsfeld suggested to him. A staff member informed him, by letter, of the exact dates of his mother’s arrest, her im prisonment at Drancy, and her deportation to Auschwitz. She’d also been posthumously granted the title of “political deportee” for the 24 days starting with her arrest and ending with the transfer of her deportation train from French to German control.

Curious as to where Veterans’ Affairs had acquired this precise information, Levendel called the agency. The bureaucrat he spoke to, while sympathetic, at first refused to reveal the source of the information. When he pressed her, she finally confided that it came from a vast card file of Jews marked for arrest — one of a pair compiled during the war by French officials. The card file for the Paris region alone comprised more than 150,000 entries.

“How does one get to look at it?” asked Levendel.

“You can’t,” answered the bureaucrat. “French law forbids the existence of racial records. Therefore, the card catalog doesn’t officially exist.”

“But you just told me it exists.”

“Only privately. On the record, I’ll deny it.”

Veterans’ Affairs could not send Levendel an official copy of his mother’s card, no matter how much he wanted it, if it didn’t exist. But the bureaucrat, in a private act of kindness, sent him a copy of the card in a plain brown envelope without a return address, as if it were pornography.

The fiction of the nonexistent card catalogs did not hold much longer in France. In fall 1991, a furor erupted when the newspaper Le Monde, acting on a tip from Serge Klarsfeld — exposed the existence of the catalogs. Had they been the creation of the Nazi occupiers — themselves so adept at paperwork — the French would not have been so sensitive to the discovery of thousands of moldering cards representing Jews targeted long ago. But these catalogs were as French as the Eiffel Tower. Originally a tool, they now became a reminder of the nation’s participation in an inhumane undertaking. Robert Paxton, a pioneering historian of Vichy, points out that Theodore Dannecker, the Nazi who oversaw the policing of French Jews, had admired the thoroughness with which the French cataloged the Jews.

Levendel’s obsession with old documents inevitably put him in contact with others named on them — in one instance, with heart-stopping results. At a Holocaust lecture given at Northwestern Unviersity in the spring of 1993, he struck up a conversation with two older women speaking with French accents. Levendel learned that they were sisters now living in Skokie who had spent the war years as teenagers in the Vaucluse.

“What were your maiden names?” Leventdel asked.

“Edith and Rose Margolis,” they answered.

From his briefcase, Levendel produced a copy of a typed list — dated August 7, 1942, and marked SECRET — of the names of 111 Jews marked for arrest in the Vaucluse. It included the names of Edith and Rose Margolis. The sisters were so stunned that Levendel feared a doctor might be needed. They’d never known the arrest list existed. But they had been cautious enough to go into hiding nearly two full years before Sarah Levendel came to that same decision. They were among half of the targeted Jews on that list to evade arrest.

The document that brought Levendel closest to his mother during four years of searching didn’t come from state archives. He found it at the Jewish Documentation Center in Paris. It’s a handwritten personal property receipt from the Drancy transit camp: “Received from Madame Levendel, Sarah, Le Pontet, Vaucluse, the sum of 485 francs and a gold Tissot wristwatch. June 13, 1944.” The receipt was signed by the camp police chief. It all seems so proper that one might think the property was only in temporary safekeeping.

On a dreary April morning two years ago, Levendel journeyed to Auschwitz aboard a chartered train from Paris. The 800 passengers were mostly children and grandchildren of Jewish deportees who were marking the 50th anniversary of the first deportations from France. Amid the usual departures to other European cities on the schedule board at the Gare de L’Est, it was startling to see posted that day, probably for the first and last time, a 7:15 express to Auschwitz.

In a cold drizzle, Levendel walked beneath the camp’s infamous high portal through which trains entered. Ahead was the double ramp where his mother had been unloaded. “I walked as fast as I could along her Way of the Cross toward the gas chambers and crematoria,” he remembers. “Yet time passed so slowly I didn’t seem to be moving.” Finally, he was standing before the ruins of one of the four killing facilities, still imposing even after being dynamited by the Nazis as they fled the Red Army in the winter of 1945. His first goodbye to his mother had been in the cherry orchard. This one, at graveside, was 1,000 miles away and 47 years later.

A final question remained unanswered: Who had arrested Sarah Levendel? “I long wondered what my reaction would be were I to meet those ‘steel-hearted’ Frenchmen,” says her son. “One side of me was tempted to make them go through the hell she went through. The other side was relieved that I didn’t have to face them because they were probably dead.

An acquaintance put Levendel in touch with Paul Jankowski, an assistant professor at Brandeis University and expert on the rise of fascism. Jankowski suggested that the two men might have been members of a gang based in Marseilles that at first caught members of the Resistance on behalf of the German SD (security police), then branched out to arrest Jews. Its leader was named Charles Palmieri. In 1944, his gang had roamed well beyond Marseilles — even to the Vaucluse.

In 1992, Levendel’s request to gain access to the regional archives in Marseilles had been rejected by a functionary. Trying again last spring, he spoke directly to the archives’ director of contemporary records, Christian Oppetit, who offered to help. Oppetit agreed with Jankowski that the thug Palmieri was a prime suspect. But the file on Palmieri’s trial for treason in 1946 was classified as top secret for reasons of “national security.”

Last April Levendel was granted special permission to view the Palmieri file. He flew to France and, under the watchful eye of a guard, pored over the file for two days in early June — almost 50 years to the day since his mother’s disappearance. Palmieri had indeed arrested Jews in several towns in the Vaucluse on June 6, 1944, using lists supplied to him by French authorities in Avignon. Two German Gestapo officers were also on hand, though they seem to have allowed Palmieri to handle the arrests.

At ten o’clock that morning, Palmieri and four henchmen first swept into the village of Orange, where they arrested a 68-year-old Jew named Jerome Nicoli. “Where was the rest of the family?” asked Palmieri.

“Elsewhere,” Nicoli insisted.

Palmieri put a gun to his head.

“Tell us the truth, or I’ll kill you,”

“I’ve said what I’ve said,” answered Nicoli evenly, “Shoot.”

Palmieri didn’t shoot. But after catching Nicoli’s daughter on the street moments later, he did release the two of them in return for ransom of 150,000 francs — big money at the time. The gang also stripped Nicoli’s home of valuables.

Palmieri’s five-member gang arrived in Le Pontet about noon. They arrested seven Jews, including two children. At the home of the Benyacar family, they offered to release Moise Benyacar, testifying at Palmieri’s trial, remembered seeing Sarah Levendel there. He alone from his family survived Auschwitz, Buchenwald, and Dachau. In convoy 76, his son Sylvain was the youngest of the 1,150 deportees.

Palmieri fled to Germany with his SD masters barely a month after he arrested Jews in the Vaucluse. Slipping back into France in 1945, he was arrested in Paris and returned to Marseilles. A psychiatrist found him to be “very calm, fully in control of himself and … perfectly able to understand the charges against him.” Defending himself, Palmieri claimed he had not intended to violate national security. All he’d wanted to do was to “fight against internationalists and Jews.” Rather than being executed by a firing squad, as traitors normally were in postwar trials, Palmieri was guillotined like a common thief.

After handing back the file on his mother’s murderer, Levendel packed up and went home to Naperville. In the Vaucluse, 50 years after he’d waved his final goodbye to her, the cherry orchards were once again in bloom.