|

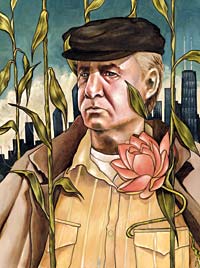

Illustration: Lisel Ashlock |

J. J. Jameson’s final poetry reading didn’t go so well. It took place on an unseasonably warm February night at Coffee Chicago, a quiet little café in Edgewater frequented by homeless people during the day and bohemian poetry fans each Friday night. Jameson drew a crowd, as always-30 or so people packed together to hear his salty, self-deprecating poems. It was supposed to be a comeback of sorts-Jameson, the loud, drunk, curmudgeonly, 65-year-old vagabond poet who had set himself up as a sort of court jester and wise fool to the Chicago poetry scene, was emerging from yet another lengthy bout with yet another attack of one of his many chronic ailments. Something about jaw surgery this time. But the night took on a somber, valedictory feel. The man of honor did not wear the foppish suit, suspenders, and bow tie he usually donned to read his poems in public; instead he was in his shabby work trousers, a T-shirt reading “Manure Movers of America,” and a brown fur hat that sat too high on his head. He wobbled a little as he approached the microphone, owing to the extra Vicodin he had swallowed earlier that night to take the edge off the pain in his jaw. He struggled through a couple of poems, but it hurt too much to talk, and the painkillers wouldn’t let his mouth form the words right.

It was going south. But Jameson, moist eyes twinkling under the café’s track lighting, with his hangdog jowls and crooked smile, didn’t want to disappoint. So he called surrogates up to the stage to read his poems in his stead. With some embarrassment, his friend Shelley Nation, a bespectacled redhead who wouldn’t look out of place at a Metallica concert, read “The Puttering Penis,” Jameson’s puzzled response to the long-running play The Vagina Monologues. As the evening wore on, Jameson became increasingly undone. There is some dispute as to whether he was drinking that night, or if it was just the pills, but he became loud and began indiscriminately bear-hugging members of the audience. He created enough of a ruckus that John Starrs, the white-bearded poet who emcees the Friday night readings, later apologized for Jameson’s antics to the woman slinging coffee behind the counter. She didn’t mind. Starrs, though, thought Jameson didn’t look so good, and made a mental note to keep in better touch. He didn’t know how much longer Jameson would be around.

When it was time to go, Jameson’s friend David Gecic, who runs The Puddin’head Press, a specialty publishing house that printed Jameson’s first and only book of poems, tried to take his keys. But Jameson grew angry-he had a starchy, willful independent streak that, like his accent, marked him as a New Englander-and he wouldn’t give them up. Gecic knew the drill. So he waited for Jameson to stumble to his beat-up Oldsmobile and followed him home to his Austin apartment. To make sure Jameson drove inside the lines, Gecic placed a blue hardhat up on the driver’s-side dash in the hopes that Jameson, looking into the rearview mirror with bleary eyes, would mistake him for an unmarked squad car. If he thinks a cop is tailing him, Gecic reasoned, he’ll drive carefully.

If he’d only known.

J. J. Jameson had been a fixture among Chicago’s so-called saloon poets for nearly 20 years. He had published a book. He was about as close to being a public intellectual as an alcoholic day laborer could become: he passionately defended labor rights on cable-access television, discussed poetry on independent radio, and lionized the memory of the Revolutionary pamphleteer Thomas Paine from the podium of the College of Complexes, a weekly debate group that attracts outsiders and political obsessives. He campaigned for Mayor Harold Washington’s 1987 re-election, arranging for gang members in the Ukrainian Village neighborhood to drive little old ladies to polling places. He once put in a call-and got through-to Mayor Daley to push a pet project in Humboldt Park. He fought valiantly to save the Maxwell Street district from development. He was deeply involved in the affairs of his 140-member Unitarian church in the Austin neighborhood, serving as chairman of its board for one year, attending services regularly, and looking after the aging congregants. He loathed guns, and he worked with the police in his neighborhood to combat gang activity. He cultivated hundreds of often intense friendships with people of all stripes in Chicago, from Communists to nurses to chemists to established writers to teachers to bums. He was a fiercely loyal friend.

He also murdered John Pigott in Saugus, Massachusetts, in 1960. And he pleaded guilty in the death of jailmaster David Robinson in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in 1961. And he escaped from a state prison near Walpole, Massachusetts, in 1985, and fled to Chicago, eluding capture for two decades. On a blustery March morning a little over a month after that night at Coffee Chicago, a team of Massachusetts investigators finally caught up with Jameson. They called him by his name, Norman Porter, and took him home.

And so Jameson the poet was revealed to be Porter the killer, and together they became the Killer Poet. Photos of Norman Porter, forlorn and handcuffed, made the front pages in Chicago and Boston. In Hudson, Massachusetts, the woman who had been set to marry Pigott-she called him Jackie-when he was gunned down in a botched robbery 45 years ago celebrated the news with a cake made especially for the occasion, with “Caught” spelled out across the top in icing. In Chicago, David Gecic fled the siege of press calls-the Web site for The Puddin’head Press, complete with Gecic’s contact information, was one of the first places Googling reporters landed looking for information about Jameson-for a friend’s farm to stare into a bonfire and collect his thoughts. Both of them faced the same puzzle, but from opposite directions: How can a man you think you know to the bone end up being so radically different?

|

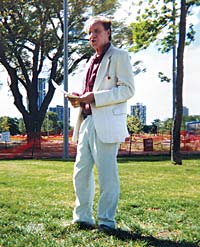

Courtesy The Puddin’Head Press |

|

Porter taking a break in Lincoln Square during the 2004 Chicago Poetry Festival. |

His clothes never fit right. That’s the one thing you hear from people who have known J. J. Jameson over the years, and it is true of Norman Porter as he sits across from me in an interview room at MCI–Cedar Junction, a state prison in South Walpole, on a sweltering June day. He looks underfed and frail in his baggy blue-green jump suit. Porter is garrulous, charming, and slightly goofy. He has a certain stubborn dignity that comes across as almost comical in undignified situations, whether it’s the physical and sexual depredations he wrote about in his poems or sitting across the table from me in his thin V-neck prison blouse. One friend describes him as Chaplinesque. Don Knotts could play him in the movie.

And let there be no doubt that Porter would like there to be a movie. (In fact, a Boston-based documentary crew has already interviewed Porter in prison.) He has already started his memoirs, he says, and it is immediately apparent to anyone who meets him that Porter is taken with what he believes to be the sweeping, romantic narrative arc of his life: the man who entered prison a thug and left it a thinker; the neglected weed that grew up from the concrete and turned out to be a flower.

Norman Arthur Porter Jr. was born on January 28, 1940, in Woburn, one of four children. “On a dirt road with an icebox, not a refrigerator,” he says. His father owned a business drilling water wells and, later, moving homes to make way for new highways.

“My father was strict,” Porter says. “New England strict. There’s a breed of Puritanism my father shared.” He put his children to work early, and Porter points a proud finger in the air between us to emphasize that he worked hard for his father’s business from the age of eight. But by the time he was 13, he says, he had started getting into trouble. He stole a car when he was 15-as with most of Porter’s crimes, he brings up muddying and mitigating circumstances for this juvenile arrest, saying he’d been wrongly accused-and was sent to the Lyman Reform School for boys. His parents, hoping to teach him a lesson, did not object to the sentence. “I was not right for the next seven or eight years,” he says. “It was a brutal place. They beat the shit out of you.”

For Porter, past was prologue. He cut his teeth on jailbreaks by busting out of Lyman “about 18 times,” he says. He’d steal cars and hit the road until he was caught, which he always was. He once got as far as Richmond, Virginia, where, he says, he went to visit Civil War battlefields-an early emergence of what would later become a recurring theme in his life, that of the intellectually curious outlaw. Eventually, he met Teddy Mavor and John Deveau.

“Three guys went to rob a place and it went haywire” is how Porter describes the events of September 29, 1960. According to court documents and contemporaneous press accounts, Porter, Mavor, and Deveau were relatively accomplished holdup men in the midst of a crime spree when Porter and Mavor walked into the Robert Hall clothing store in Saugus, a working-class suburb north of Boston, around 8:30 that evening. Porter was out on bail awaiting trial for three felonies in Boston, and later police would link the trio to a grocery store holdup from two weeks before and an attempted bank robbery that very morning.

Porter and Mavor, wearing blue-and-white-checked bandannas over their faces and felt pork-pie hats pulled low over their eyes, walked into the Robert Hall store and announced a holdup. Mavor, who had worked at the store a few months earlier and so knew the layout, was carrying a pistol; Porter carried a sawed-off shotgun and had a pistol in his belt. Deveau waited in the getaway car. They were expecting the store to be closing down, but it had stayed open late to accommodate the back-to-school rush, and there were 20 to 30 shoppers inside. Mavor and Porter herded everyone to a back room. While Mavor took the store manager into the office and demanded that he unlock the safe, Porter shook down the customers. He pulled a checkered raincoat from the rack and handed it to Jackie Pigott, who worked nights as a clerk at the store, saying, “Put your wallet in this.” Pigott didn’t carry a wallet. “Well, put your money in it, then.” Pigott produced two ten-dollar bills, but he was nervous and had trouble getting the bills into the raincoat pocket. The woman standing next to him tried to help by holding the coat steady. For some reason, Pigott turned away from Porter. And for some reason, Porter raised his shotgun and shot Pigott in the back of the neck, killing him.

Then he reached down and picked up the two ten-dollar bills in Pigott’s left hand, and said, “Now you know I mean business.” The raincoat was passed to the next customer.

One of the employees picked up a stepladder and hit Mavor over the head with it, knocking him into the store’s manager, Ralph Fabiano. Mavor and Fabiano began wrestling over Mavor’s pistol, and it went off, hitting Fabiano in the left side (he survived). Mavor and Porter gave up on the robbery and fled. They had made $411. Deveau, perhaps having heard the gunshots while waiting in the car, had lost his nerve and was gone when they got out.

Claire Wilcox, Pigott’s girlfriend at the time, was 19 years old. When I asked her in June at her Hudson apartment to tell me about Pigott, Wilcox, a forceful and plainspoken 64-year-old grandmother of four with an easy laugh, said simply, “There’s not a whole lot of life to tell you about.” Pigott was 22 when he was murdered. His father was the vice president of a local bank, but Jackie had a job digging ditches for the local gas company. He was the kind of guy, Wilcox said, who would show up for work in the morning with coffee and doughnuts for everyone. He had a quick smile, she said, and “the happiest eyes.” Though they weren’t engaged, they were planning to marry, and he had taken the job at Robert Hall to save up for the wedding.

Wilcox was at her parents’ house, waiting for Jackie to come by after work. It was getting late, after ten, and the phone started to ring. Her parents answered, and began to look worried, but they wouldn’t tell her what was wrong. From across the room, Wilcox could hear that someone was screaming hysterically on the other end of the phone. “And then my father walked in, and he handed me my first-my very first-Manhattan. And he said, ‘You’d better drink this.’ And then it was just chaos.”

Local police caught Mavor and Deveau within hours, and Porter was caught two days later in upstate New York on a traffic stop. Mavor told police that Porter was the one with the shotgun. Porter confessed in New York that he had been carrying the shotgun and shot Pigott.

Porter now says that he wasn’t the one with the shotgun, but was in fact the one who carried the pistol and shot Fabiano. Mavor was murdered in prison in 1972. Since both men wore masks, neither was positively identified. But the available record strongly points to Porter: aside from Porter’s own confession and Mavor’s account, contemporaneous witness statements are unanimous in saying that the shorter of the two men-Porter-carried the shotgun and killed Pigott. Gordon Walker, Porter’s longtime attorney, says those statements were coached by the police, who were intent on making Porter the triggerman because Mavor was willing to testify to that.

Walker says that Porter’s confession in New York was coerced-Porter claims that he was kept awake for 30 hours straight. Walker raises some other potentially compelling points-among other things, Porter’s confession states that he was attacked with a stepladder, and the employee wielding it said he attacked the man with the pistol, not the shotgun. The dispute will never be definitively resolved, but Massachusetts state courts have found that Porter carried the shotgun, and he eventually pleaded guilty to possession of a sawed-off shotgun. At Porter’s sentencing, his own attorney, Paul Smith, clearly acknowledged that Porter was the one with the shotgun by arguing that Mavor was the heist’s ringleader because he had been the one to go to the safe with Fabiano.

In May 1961, Porter was in a Cambridge jail awaiting trial for the Pigott murder when he pulled a pistol on the guard escorting him back to his cell from a visit with a psychiatrist. “A guy gave it to me,” he tells me when I ask him how he had smuggled a pistol into jail. “Back then, at the East Cambridge jail, you could reach out your hand and touch people walking by on the sidewalk.”

Porter walked with the guard down a hall to a room where a fellow inmate, Edgar Cook, who was awaiting trial for the murder of a Boston police officer, was meeting with his lawyer. He waved Cook out of the room, and the two headed for the door. Before they could escape, they encountered David Robinson, the jailmaster, who stood his ground and demanded that Porter hand over the gun. Cook told Porter to shoot him. Porter hesitated. Robinson made a move for Porter. Cook grabbed the gun. He shot Robinson behind the ear. It was Mother’s Day, and Robinson, a 30-year veteran law enforcement officer with a wife and two kids, wasn’t supposed to be there; he had traded shifts so a few of his men could be with their mothers.

Cook was found three days later at a friend’s apartment by the Boston police. His death was ruled a suicide, but everybody I talked to who was familiar with the case suspected that it was a police murder. One crime scene photo shows Cook’s pistol, hat, burning cigarette, and a pool of blood lined up in a tidy row on the floor. Porter was caught in New Hampshire one week later while robbing a food store. A photo taken in court the next day shows Porter, smiling, arms folded confidently across his chest, amiably chatting up the two New Hampshire State Police patrolmen who had arrested him.

Porter pleaded guilty to second-degree murder in both cases. He was sentenced to life in prison for Robinson’s murder and life in prison for Pigott’s murder, with the sentences to be served consecutively. In other words, as his lawyer puts it: “You serve life for Robinson’s murder, then you die, and then you start serving life for Pigott’s murder.”

|

Courtesy The Puddin’Head Press |

|

Porter at the regular reading once held near North Avenue Beach. |

Norman Porter went to prison at exactly the right time, in exactly the right place. It’s safe to say that had he committed his crimes in Texas, he would have been long dead by now. And had he been born a decade or two in either direction his prison experience would have been quite different from what it was. But he happened to enter prison at the very beginning of a prison reform movement that had as its epicenter Massachusetts.

“From 1965 to 1975, it was prison reform at its best,” Porter tells me. And he became its poster boy. Porter went to high school in prison. He hit the books. He participated in a program started by Elizabeth “Ma” Barker, a Boston University professor and lifelong prisoners’ rights advocate, who held college poetry classes in the prison. He graduated from high school and earned nearly enough credits at Boston University-including a seminar in criminology-to graduate, though he never received a degree. He started Radio Free Norfolk, a weekly half-hour show broadcast from within the Massachusetts Correctional Institute at Norfolk on WBUR, a Boston public radio station. The show won a 1973 Citation for Excellence in Public Service from United Press International. He also launched a prison newspaper.

His efforts at rehabilitation earned him a celebrity status among the Boston intelligentsia that is almost unthinkable today: he eventually earned the right to 14 days of furlough a year and says he attended seminars at Harvard University, where he met John Cheever-rather dubiously, Porter claims to have assisted Cheever with his novel of prison life, Falconer. (Blake Bailey, the author of a forthcoming biography of Cheever, says that it is highly unlikely the two ever met: Cheever based Falconer on his experiences teaching at Sing-Sing prison in upstate New York, and met more than enough inmates there to provide him with details. Bailey found no mention of Porter in Cheever’s detailed and voluminous journals.)

Porter claims to have hobnobbed with the poets George Starbuck and X. J. Kennedy and with the writer James Carroll. (Starbuck is dead and Kennedy recalls meeting Porter briefly; Carroll did not return several phone calls to his home and to The Boston Globe, where he writes a column. But Christopher Lydon, a Boston radio host who was a member of Ma Barker’s circle, says he remembers Carroll as being involved with Porter’s case.) While on furlough, Porter would give lectures on poetry and prison reform at churches and colleges, earning $50 per engagement (he also worked days as the prison’s carpenter, building and repairing furniture).

He became a prison trusty and was moved to minimum security facilities. In 1975, then–governor Michael Dukakis commuted the sentence for Robinson’s murder and Porter began serving the sentence for Pigott’s murder. The Robinson family wasn’t even notified. When Porter applied three years later to have Pigott’s murder commuted, Jackie Pigott’s cousin Dottie Johnson caught wind of the request. Dukakis recommended the second commutation, but Johnson showed up at a meeting of the Governor’s Council, which normally functions as a rubber stamp for the governor’s recommendations, with 5,000 signatures from Massachusetts law enforcement officers opposing the commutation. The effort was scuttled.

“The late sixties and early seventies was a period of great reform,” says Dukakis, today a professor at Northeastern University in Boston. “I was very committed to education and job training. In the Porter case, [the state Advisory Board of Pardons] recommended commutation, and it was based on what appeared to be a very impressive record as a prisoner. He was a very responsible inmate within the system-you need these kinds of people or otherwise the place will blow up. And something snapped in him or something, and he said, ‘I’m out of here.’ I wasn’t happy.”

In fact, something snapped twice. Porter walked off the grounds of a minimum security prison in 1980, only to turn himself in two days later. He was never charged; Porter insists that he was lost in a fog of depression over the thwarted commutation and “wandered” away. By Porter’s count, it was his 20th escape.

It turns out to have been a dry run for number 21. Porter continued to push for commutation, but by 1984 it was clear that Dukakis had presidential ambitions and could no longer afford to be generous to murderers. (Indeed, it was publicity surrounding the furloughing of one of Porter’s fellow inmates, Willie Horton, that may have cost Dukakis the White House four years later.) So on the day before Christmas Eve in 1985, Porter walked out of the Norfolk Pre-Release Center, where inmates were permitted to sign themselves out for strolls. He was seen making a call on the prison pay phone minutes before he disappeared. Porter claims he had buried around $3,000 in Ziploc bags in the woods that bordered the prison. He tells me he earned the money from prison work and speaking engagements; when I express doubt, he points an accusatory finger and says, “I worked very hard, young man.” In any case, he says he dug it up and caught a bus to Rhode Island. Massachusetts authorities laugh at that story.

“We think he had help,” says detective lieutenant Kevin Horton of the Massachusetts State Police Violent Fugitive Apprehension Section, who started at the unit a month before Porter escaped and spent the next 20 years involved in the search. “He might have taken a bus, but he was driven to a bus station somewhere in Providence or New York; we don’t know where. There were a lot of people that were promoting him. They were all liberal academia people looking for a poster child. They found one.”

One of them was Robert Castagnola, a Boston College professor of social work who had counseled Porter in prison and whom Porter credits with saving his life. “I went to see Castagnola in 1965 and told him I didn’t want to be a thief anymore,” Porter says, and Castagnola started him on the path to rehabilitation. Shortly after the escape, Castagnola wrote a letter to The Boston Globe accusing Dukakis of betraying Porter and saying, “I fully support Porter’s escape. . . . I will be pleased if there is anything I can do to keep Porter out of the clutches of ‘justice’ and to at last be free.” Porter told me he kept in touch with Castagnola, who has since died, during his 20 years on the run, but never told him where he was.

Porter got to Chicago shortly before New Year’s Day. He had spent a few days traveling by bus up and down the eastern seaboard before heading west to Chicago, drawn by Nelson Algren’s sketches of the down-and-out life on the margins in City on the Make. “I said, Chicago-what the hell? With all them pimps and whores, it can’t be too bad.” He holed up at the Olympia Hotel, a flophouse at Wells and Ontario, and, picking the name out of a phone book, Norman Porter became Jacob A. Jameson.

The chronology of Jameson’s first years in Chicago is unclear. He says that he spent some time living on Lower Wacker Drive, drinking his days away. On weekday mornings, he would sell copies of the Chicago Tribune and the Sun-Times at an on ramp to the Eisenhower Expressway, earning around $50 by 8:30 a.m. “Then I’d get on the train and I’d go down to Zimmerman’s Liquors on Hubbard and Wells, and I’d start drinking and I’d visit every museum and place of interest in Chicago.”

David Beaton was one of the first friends Jameson made in Chicago. Beaton can’t recall exactly how they met, but he thinks it must have been 1986 when he hired Jameson to help him rehab the three-flat building Beaton owned in West Town. Jameson needed a place to live, so Beaton let him move in while he worked on the job, and they became friendly.

“He was always asking, ‘Where are you going, what are you doing; can I come along?'” Beaton says. “He was kind of like a kid brother. To be honest with you, once we became friends, I didn’t get much work out of him. I don’t think I even finished the apartment-I just sold it.”

A laid-back political progressive, Beaton wasn’t the kind to ask too many questions. It was clear to him that Jameson was struggling with alcoholism, but he found him to be lively company. “I never got the sense that he was hiding something,” Beaton says. “I got the sense that he was a creative genius who was definitely living off the grid. He told me he was from Maine, close to the Canadian border. But to me, I don’t really care about what your past is as long as you’re OK today.”

In the spring of 1987, as Harold Washington’s re-election campaign heated up, Beaton became Washington’s area coordinator for part of the 32nd Ward, which at the time included the Ukrainian Village neighborhood. As he made the rounds canvassing and leafleting the ward, Jameson tagged along. Eventually, Jameson insinuated his way deep into the campaign effort, a role of which he is still enormously proud. “They told me they’d be happy if they got 40 percent in my precinct,” Porter says. “And I got them 50 percent.”

“Those were wild times,” says Beaton, whose recollections of that era are shot through with nostalgia for the political upheaval, with Washington in the mayor’s office and African American and Latino political groups threatening the city’s white power structure. “My office got firebombed,” he says. “There’s a lot of shit that went down in those years. J. J. was there and the action was happening every day.”

Jameson met Washington himself several times during the campaign, and a signed photograph of the mayor hung on Jameson’s wall until the day he was caught. Today, Porter claims that during that time he dated Helen Shiller, then a Washington campaign worker and now a North Side alderman, and that he served as the press secretary for the aldermanic campaign of the West Side activist Emma Lozano. Through a spokeswoman, Shiller says she has no recollection of Jameson and that she was married at the time. Lozano says she didn’t have a press secretary and that, although she did enlist the help of some of Washington’s campaign workers, she can’t remember Jameson.

During those days, Beaton and Jameson would socialize as well as work the campaign. “He was an entertainer-always center stage,” recalls Beaton. “We used to have lavish dinner parties, and he’d invite people from all walks of life.”

But Jameson’s drinking made him unpredictable and unreliable, Beaton says, echoing a complaint raised by later friends of the poet. Beaton moved to Florida in 1991, and he and Jameson drifted apart. Jameson went to visit him once, arriving with little warning. Beaton says he couldn’t get time off work the next day, so he left Jameson alone at the house. When Beaton returned, most of the liquor was gone, along with some money, and so was Jameson.

Around 1988 Jameson came to the Third Unitarian Church in Austin, an aggressively eccentric collection of professionals, activists, and intellectuals who seek the community of a church without the attendant religiosity. The Rev. Don Wheat, the minister during those years, remembers Jameson showing up at the door with “rags around his feet.” Wheat arranged for David Schweig, a church member who owned some buildings in the area, to employ Jameson as a handyman and found him a place to stay, an arrangement they would repeat at least a dozen times over the next two decades.

In several regards, the church was a perfect fit for Jameson. Not only was the pulpit named for Tom Paine, whose writings Porter had come to admire in prison, but the Unitarian political philosophy was based on notions of redemption and, to put it bluntly, not asking too many questions. “It’s a place that accepts people who are unacceptable,” Wheat says. “It’s a place where everyone’s a misfit. If J. J. had said, ‘I did time for murder,’ I don’t think anybody would have drawn back at coffee hour.” Porter was raised an Episcopalian, but Jameson eagerly took Unitarianism as a central part of his identity. He looked in on the church’s elderly parishioners. He launched a daycare program that brought 40 local kids into the church each day. When Marcet Tinsley was sick with cancer, he painted her house and carried her downstairs so she could see the work. The stories are legion.

Jameson told his friends little about his background. He would often tell boyhood stories from “Maine”-about his schoolteachers, about his parents. It was clear to most that he was an educated man-he enjoyed showing off his knowledge of literature and history-but he never spoke of having gone to college. He boasted to friends that he had participated in protests against the Vietnam War and against a nuclear reactor in Maine, neither of which could possibly be true. He told people that he had two children, one who lived on the West Coast with whom he wasn’t close, and another who lived in England and was a “hellraiser.” He now claims that these children were fictional. Both of Jameson’s parents are now dead; he told me he kept in touch with them by phone while he was in hiding. And he was in contact with his lawyer, Gordon Walker-Walker’s phone number was found in Jameson’s cell phone when he was caught. He is matter-of-fact about the life he invented. “I would tell nine truths for every one lie,” he says.

Jameson first emerged on the Chicago poetry scene around 1991. He was a loud and opinionated figure, known for his inflexible ideas about what constitutes poetry, as well as for the catchphrase he hurled at poets who lingered too long in explaining or introducing their work: “Read the fucking poem!” He was a regular at Sunday night readings at The Green Mill in Uptown, at Coffee Chicago, at Higher Ground, and at a host of other bars and cafés that have since closed down. “He read often enough that everybody was aware of him in the scene,” says John Starrs, the Coffee Chicago host. “He had a whole persona. He would pretend to be gruff. Everybody loved him. Everybody laughed a lot because he was a very funny man, and you can see it in his poetry.”

Jameson’s poems aren’t bad. The better ones are written in plain language, and they have a self-deprecating charm. The worst are amateurish and vulgar. But there is no doubt from reading his work that Jameson was serious about poetry; he was no occasional scribbler. He always wore a jaunty cap, and he always kept a pencil tucked between the brim and the top fold. When his friend Shelley Nation cleaned out his car after his capture, she found piles of legal pads, which he always kept nearby.

The J. J. Jameson that emerges from reading Lady Rutherfurd’s Cauliflower, his published book, and “Lord Rutherfurd’s Rutabaga,” the unpublished collection he was working on when he was captured, is a self-lacerating romantic with a juvenile sense of humor. He writes about women and their mysteries, about his body and its steady deterioration, and, rather poignantly, about his parents and his failure to understand or please them until it was too late. “Lady Rutherfurd” is a real woman, Jameson’s friends say, a fellow Third Unitarian with whom he had an on-again, off-again relationship. She evidently believed Jameson was not good enough for her. In his poems about her, Jameson is alternately aggrieved and smitten, vicious and tender. “Their talk was the talk / of two half-old, half-baked, fuddy-duddies / who just wished to lie down / with a semi-live body / get up in the morning / go about one’s business / without head-ache of all that romantic crap,” he wrote in “The Authoritarian and the Control Freak,” before going on to document the intrusion of “romantic crap” in the relationship. The cauliflower of the title is a reference to Jameson’s thwarted attempts to ply her with flora: first a corsage, which she cruelly rejects, and later with a fresh head of cauliflower he offers to cook for Thanksgiving. She prefers frozen vegetables: “I politely told her, / I didn’t want any of her / damn frozen vegetables / and I didn’t want / any damn frozen relationship either.”

Some of the poems are startling in retrospect. “I woke up this morning / feeling someone else’s skin / around my bones,” begins “Skin,” a meditation on aging that reads now as a reference to the veil of lies that surrounded his life in Chicago. In “I Saw god Today,” in which Jameson describes an encounter with God and wonders why he allows for war, there are these lines: “God spoke: / You know young man / god gets tempted too / he gets lust in his hearth / when someone with a 410 shotgun / is breathing down / the neck of a rabbit.”

Jameson also wrote a poem called “The Lilac Fugitive,” about hiding from his parents as a child under his cousin’s lilac bush: “Hiding out from the world is an art.” Shelley Nation says Jameson personally delivered a copy of the poem to her when he completed it-the closest, she now says as she looks back, he ever came to revealing himself to her.

Of course, the poetry was his undoing. C. J. Laity, a local poet and friend of Jameson’s who operates the Web site chicagopoetry.com, selected Jameson as Chicago’s “Poet of the Month” for March of this year and placed his photograph and a bio online. It was certainly not the first time Jameson had been in the public sphere. He had given innumerable readings, and he had appeared on the cable access show Labor Beat, with his friend Bob Hercules, a Chicago television producer. He was a guest on several local radio shows, discussing poetry. Indeed, he seemed to tempt fate: he was arrested twice, once for hitting a tree with his car in 1993, and again over a billing dispute with a person who did contracting work for him. He was fingerprinted for both arrests and knew that there was a risk of a match with Norman Porter’s prints, but he chose to stay in Chicago and continue to use the same alias. When Shelley Nation was the victim of identity theft, he went with her to discuss the case with a prosecutor. For a time, according to both Gecic and Beaton, Jameson dated a secretary in the office of the mayor. Once he called and got her to put him through to Daley, so he could lobby the mayor to dedicate the renovated boathouse in Humboldt Park to a youth drum corps that used to practice there (Mayor Daley politely rejected the suggestion). Jameson did not behave like a man on the run from the law.

Porter’s advocates now use that fact to argue that he led a spotless life in Chicago, which is not true. Aside from the drinking, he was not always forthright in his dealings with friends, says Wheat, citing a time Jameson bought a computer from someone and then never paid him. Gecic, who was a friend for years and continues to support Porter, told me that his relationship with Jameson cooled in part because Gecic was uncomfortable with what he felt was Jameson’s abuse of his authority as chairman of the church board: for example, after Jameson became chairman, he directed rehab work at the church to himself and moved into a church apartment that was supposed to be rented to people in the community. Schweig, a fellow church member, says Jameson spent somewhere between $2,000 and $5,000 of church funds to buy tools and supplies for his own work elsewhere. Through his attorney, Porter denied misappropriating funds from the church and said that he did have a dispute with Schweig but that it was “quickly resolved.”

In January, the FBI began a routine crosschecking of the fingerprints in its electronic database to root out instances of duplicate prints listed under different names. The Massachusetts State Police had sent Norman Porter’s prints to the FBI, and the Chicago Police Department had sent J. J. Jameson’s prints from his 1993 arrest. Both sets were sitting in the database for 12 years before anybody realized they were identical. Lieutenant Joseph Pepe, now an investigator for the Massachusetts Department of Corrections Fugitive Unit, was a guard at the Norfolk Pre-Release Center when Porter escaped, and for 18 years had been assigned to find him. In February, he received a drab form letter from the FBI delivering the best news he had heard in years: Norman Porter had been arrested 12 years earlier in Chicago under the name Jacob A. Jameson.

Pepe assumed that Porter had done the smart thing and hit the road after the arrest, but the simple act of entering his name into an online search engine proved otherwise. There he was, Chicago’s poet of the month.

Pepe and a team of investigators flew to Chicago and on March 22nd sent a pair of plainclothes Illinois State Police officers to the Third Unitarian Church-Jameson’s online bio mentioned the affiliation. The officers didn’t want word to get out that they were on to Jameson, so they carried a random photograph of another man and asked people if they’d seen him. While they were in the secretary’s office, Jameson popped in to grab a business card. Amazed at their luck, the officers followed him out as he made for the door and showed him the photograph, asking if he’d seen the man. Jameson said no, and remarked how bad crime was in the neighborhood. They asked him his name, and when he said “J. J. Jameson,” they put him under arrest.

“Initially, there was a shock,” says special agent Todd Damasky, one of the arresting officers. “Like, ‘Oh, my God, they got me.’ But after that, as we were walking out of the church, he made the comment, ‘Well, I’ve had a good 20 years.’ He was resigned to his fate. His future had finally caught up to him.”

Gordon Walker says he hopes to secure Porter less than the maximum sentence on the escape charge, which normally carries a term of up to ten years, and hopes to persuade a judge to let Porter serve the escape sentence concurrently with the remaining years he must serve for Pigott’s murder. But the district attorney handling the case has indicated that he is in no mood to bargain. Walker also says he will eventually resurrect the commutation effort, using Jameson’s life in Chicago as evidence that Porter has been thoroughly rehabilitated. In one sense, it’s a perfectly logical argument: we don’t need to wonder whether Porter could live a relatively harmless life outside prison. He already has. On the other hand, it is uniquely perverse for Porter to claim the 20 years of freedom he stole from the State of Massachusetts as evidence in his argument for release.

His friends understand this point, but they want to see him again. “I don’t know,” Gecic says when I ask what should be done with Porter. “He did lots of good stuff here. I mean, there were old ladies he made sure could get their groceries. And he helped a lot of people kick their drug and alcohol habits, even though he couldn’t kick his own. But there was nobody to keep score. Because he left-because he escaped, there was nobody to keep score and see those things that he did. So they don’t count.”

“He has the keys to my house and to my car,” says Nation. “If he came back tomorrow, he would still have the keys to my house and my car. I trust him completely. Something that has been done in the past doesn’t change the J. J. I know and love. I believe that Norman Porter died in prison those many years ago. And J. J. Jameson, the whole person, came out that way.”

Don Wheat, the former Third Unitarian Church minister, says he has complicated feelings on the whole subject.

If your liberal tendencies lead you to support Porter’s release, Wheat says, what are you to say about the case of Edgar Ray Killen, the Baptist minister who was convicted in June of manslaughter in the 1964 deaths of three civil rights workers in Mississippi? “Everybody at Third Church would say, ‘Nail the bastard,'” Wheat says. “But J. J., they’d say he was helping society. I’m really mixed on this.”

Dottie Johnson, Pigott’s cousin, allows that J. J. Jameson may not have been a bad guy. “The things that he did I’m sure were appreciated, especially at that church. But there is still that life,” she says, referring to her cousin. Porter “still has a debt to society.”

There is a very good chance that Norman Porter will die in prison. If, as is likely, he receives the maximum sentence for the 1985 escape, he will not be eligible for parole until 2019. And parole is unlikely to be granted to a man who maintains, as he did to me, that his escape was “an act of civil disobedience” on a par with acts of Henry David Thoreau. He says he has suffered several bouts with cancer, and has by all accounts led a hard life. He looks much older than his 65 years.

Porter seems to know his fate, and he is keenly aware of how lucky he was to live 20 unmolested years of freedom-even those cold nights on Lower Wacker-in Chicago. There is no doubt, even to him, that his life has measured up far better than he deserved: “I’ve had a great life,” he says. “I’ve been very fortunate, for a guy who should have been hogtied and sent to the nut house.” When I asked him how he lived in Chicago-meaning how he got by-he flashed a broad smile and said, seeming to savor every syllable, “Wonderfully.”

But MCI–Cedar Junction is not so wonderful and does not appear to be as hospitable as Norfolk was when Porter was the jailhouse intellectual. He spent his first weeks at Cedar Junction in solitary confinement-the prison thought his celebrity status might be disruptive-which was tough on him. When I met with him, we were accompanied by a Massachusetts Department of Corrections press minder who had ferried several other journalists.