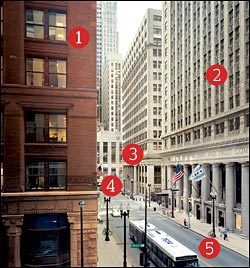

From his third-floor office in the LaSalle Bank Building (135 S. LaSalle St.), the bank’s president and CEO, Norman Bobins, not only keeps watch over the heart of the city’s financial district but has a front-row view of several gems of Chicago architecture. And though he’s not in a penthouse and the lake is nowhere in sight, “I wouldn’t trade [the view] for the world,” says Bobins.

Photography: Nathan Kirkman |

1. Built by the firm of Daniel Burnham and John Root in 1888, The Rookery (209 S. LaSalle St.) is named for where the birds-not to mention the politicians-roosted on what was once, briefly, City Hall. The construction of this Chicago landmark employed Root’s innovative “floating foundations” system that interwove iron rails with concrete rafts, giving extra support on the city’s then marshy surface. Burnham and Root kept their offices on the building’s top floor.

2. Originally called the Continental Commercial National Bank, the building now simply called 208 South LaSalle Street broke records in 1911 as the city’s most expensive proposed new development, exceeding $10 million. Three buildings, including the Rand-McNally Building that had served as the headquarters of the World’s Columbian Exposition, were demolished for the new construction. Completed in 1914, the 20-story Burnham-designed building was also one of Chicago’s tallest structures.

photography: Rob Goodwin |

| LaSalle Bank Building

Marshall Field IV kept his private apartments on the 43rd and 44th floors (now home to private dining areas and a grand ballroom) of what was then known as the Field Building (1934). The million-square-foot structure was the last major office building completed in Chicago before the Great Depression and World War II caused a two-decade delay in new construction. |

3. The Greco-Roman columns of the Federal Reserve Bank (230 S. LaSalle) and 208 South LaSalle show the popularity of neoclassical architecture during the American Renaissance movement of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. This classical-inspired style was meant to impress and project a sense of financial security. The interior of the Fed, however, was state of the art when it was built in 1922-and included one of the first building-wide wired communication systems.

|

Photography: Bill Holmes |

4. In 1930, the firm of Holabird & Root constructed the fourth and final Chicago Board of Trade building, home to the country’s central grain exchange. Atop its 45 stories, a six-ton statue of Ceres (Roman goddess of agriculture) by the sculptor John Bradley Storrs stands 31 1/2 feet high. Far below at street level, the foot of LaSalle, crowds have a way of congregating: last October, nearly two million fans-the largest public gathering in Chicago history-watched the White Sox championship parade.

|

5. LaSalle from Adams Street to Jackson Boulevard became known as the “LaSalle Street canyon” in the 1920s and ’30s, but even earlier the area produced some of the city’s tallest structures, thanks to the nearby Board of Trade. The Home Insurance building (1885), shown below, which stood at LaSalle Bank’s current location, used a steel-frame skeletal construction-a revolutionary idea that, according to some historians, made it the world’s first true skyscraper.