The Heritage Motel sits across from a pawnshop on a highway that gets you in and out of Carbondale. You’d recognize motels like it from road trips through small towns almost anywhere in America, relics of the 1950s — single-story structures with long, covered porches and side-by-side rooms. Perched on a hillside, the Heritage is close to the university where I’d taken a teaching job, commuting down on the train from Chicago and making the motel my home for three days a week. The anonymous, out-of-the-way setting, 300 miles from the distractions and headaches of the city, was supposed to offer me more time and peace to write. It had already taken me four years to finish half a novel, and I was tired of watching the shoreline of what I’d intended in life receding into the distance.

To get around town, I bought a red-orange bike with steel panniers off Craigslist, and each week when I’d head back to Chicago, I’d lock it up at the Amtrak station. When the bike was stolen, it felt like déjà vu: It hadn’t been that many years since someone had broken into the condo I shared with my wife and kids and nabbed our bikes. So much for leaving the headaches of the city behind.

I noticed that many of the other guests at the Heritage also used bikes to get around. I’d seen the rides locked to the porch support posts. Had these people sold their cars? Lost their licenses? One of them, a 40-ish black man in a blue pea coat, would pedal past my window from time to time. Maybe it was the coat or the way he held himself, but he didn’t seem to fit his rural downstate surroundings, and I wondered if some of the others staying here — people seemingly in between jobs, homes, or spells of good luck — were from somewhere else too.

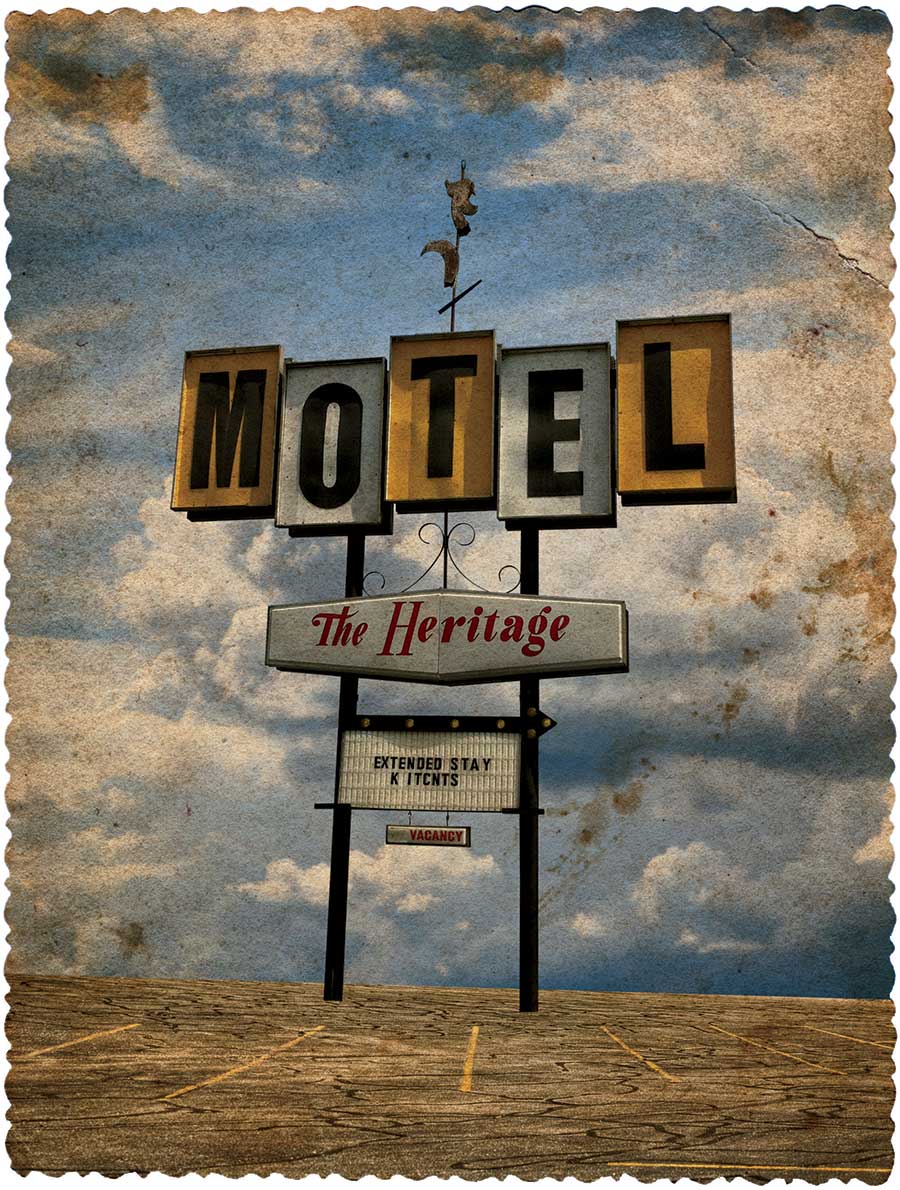

At night the motel’s roadside sign — large black block letters set in Scrabble-like yellow and white squares — went completely dark, as if the owners had never heard of light bulbs. I noticed this more keenly when winter set in and the day-to-day operation of the Heritage — normally handled by an elderly White Sox fan who lived in Florida during the cold months — fell to an ever-changing rotation of friendly but mostly inept assistant managers. They, too, seemed like they were just passing through.

With the boss away, things at the Heritage took a turn for the worse. After dark, I could hear the boom of bass. Bottles clacking. Laughter. I willfully played all this down in my head, but sometimes the motel’s nocturnal life would intrude into mine. One night some dude woke me up at 3:30 in the morning, knocking on my window with his pipe, looking for weed. Sometimes the police showed up. Red and blue lights strobed off the guest room windows. People were cuffed, carted off. Why was I here again?

Most of my bike-riding neighbors stayed in their rooms during the day, one of the few exceptions being the man in the pea coat. He struck up a conversation with me one morning as I was unlocking my bike — a used Trek I’d bought to replace the red-orange number — and getting ready to head to campus. The man was heavyset, friendly. He seemed to know bike stuff: how to WD-40 this and that, how to ride at night with red lights clipped to your clothes or your gear. He told me his name was Wes.

We laughed about the recent bad weather, ice on the roads, crazy drivers. I said I’d taken a tumble after hitting a patch of ice the night before under the darkened motel sign. I’d lost my six-pack of beer and frozen dinners down the slope. Wes shook his head. He wanted to know why a university professor was riding a bike around Carbondale in winter, staying at an old motor lodge. I told him I was saving money and needed a quiet place to work.

“Quiet?” He gave me a sideways look and grinned. “You see the cops haul off that meth head and his girlfriend?”

“It’s not so bad,” I said, more to myself than to him.

I asked Wes what had brought him here. He stood there in the sun beside his bike for a few moments, watching people go in and out of the pawnshop across the highway. Then he started telling me about his life.

He said he had been in a gang on the South Side of Chicago. Had been brought up in the gang, really. Used to bust some heads. When he was 16, that was the initiation. He and his friends would go out at night and come up behind some random someone at a street corner and, bam, down he’d go. Lots of stuff like that. Terrorizing. He was in the gang for years, ran stuff, did stuff. And then he got to be 38 years old. Just turned around and there he was, an old gangbanger. Flecks of gray in his beard. He wanted a way out. But, see, there wasn’t one.

Then he had this idea. Wes’s dad was from downstate, around Carbondale. So Wes came up with this story about his dad: cancer, chemo, tough times. And in the end, the gang leaders let Wes come downstate to take care of him.

But the thing is, his dad didn’t actually live downstate anymore. That was just a story to put folks back in Chicago off the scent. It was the only way he could think of to leave it all behind. He said he had things he wanted to do. That gangbanger stuff is fine when you’re young and don’t know anything. When you’re just getting by. But when you’re grown? He trailed off.

So, did he leave it all behind?

He shrugged, said the only heads he was busting these days were on his Xbox in his motel room. That’s what he did most days. Worked a restaurant job early evenings.

I asked him what he wanted to do.

“Own something, you know? Raise a family.”

For a moment, he seemed to slip back inside himself and started talking about the kind of tires I needed to get for my Trek. Then he told me he’d gotten in some trouble recently. Gone to a club where some stuff was going down. He didn’t know what it was. Next thing he knows, he’s in a fight and people are running, screaming. Someone fires a gun. “Somebody put something in my drink,” Wes said. “I don’t even remember. But they say I did some stuff.” The police came, and he spent some time in jail. Now he was tied to a probation officer here in Carbondale. He shook his head, pursed his lips.

I said something lame, like, “Sorry to hear that.”

Wes stared off at the Heritage sign for a bit, like he was thinking of something else, his future family, maybe. His own shoreline in the distance.

Finally, by way of parting, he said, “Peace,” and rolled his bike up the hill toward his long-term unit with a kitchenette.

A few weeks later, after another ice storm, I layered up, went outside to unlock my bike, and saw an older man in a red scarf coming out of his room, two doors over from mine. I waved. He waved back and started unlocking his own bike. “Be safe!” he said as he got on and started pedaling down the slope. The bike was red-orange with steel panniers.