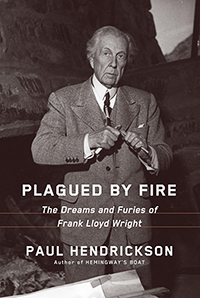

Excerpted from Plagued by Fire: The Dreams and Furies of Frank Lloyd Wright by Paul Hendrickson, to be published in October by Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © 2019 by Paul Hendrickson.

Sometimes, in spooky ways that could never be explained, it seems as if the histories of certain Frank Lloyd Wright houses reproduce his own history of calamitous fall, improbable comeback, lurid headlines, quiet beauty, incalculable sorrow, financial desperation, sexual intrigue, unsolvable riddle, and, not least, the determination to survive — no, to triumph.

There’s even fire, not to say front-page suicide and murder of a ghastly kind, attached to the story of the long-lived B. Harley Bradley House, which sits now, as it sat then, in my parochial ’50s childhood, at the very bottom of the same street I lived on, South Harrison Avenue, in the river town of Kankakee. Kankakee: an old Indian name, possibly from the Potawatomi, said to mean “swamp country.” It fits. There’s been a lot of sinking in this house. And yet it’s here, or maybe better said, she’s here, for there’s almost a palpable feminine quality to this magnificent great ship on the prairie that has lasted a century and more, in spite of all.

It’s been said this is the first Frank Lloyd Wright house that looks like a Frank Lloyd Wright house. The Bradley, so huge then, so huge now, came right at the tick of the new century, 1900; or, more figuratively, came out of Wright’s head just as the second hand was sweeping toward midnight, taking him to a new place and level and fame. More than any other Wright creation, this is the key and penultimate transitional work to all of the full-bloomed Prairies immediately ahead. But I had no clue of that then. I wonder if I’d even heard the name Frank Lloyd Wright. I was just a Catholic kid on my three-speed, gazing over at the thing he’d made, a little afraid of it, terribly pulled to it.

First, architecturally: He built it in the cruciform plan, and he made the main axis of the cross the living room and the kitchen. To situate you: The living room is located on the first floor directly beneath a low projecting gable at the front, on the second floor, with its deep overhanging eaves. Even on canvas-dreary February Midwestern days, there can be wonderful light in this room, which is the central one of the house, and it filters and fractures through the polygonal bay windows that are tied together with cocoa-colored bands of wood trim. The ribbon art-glass casement windows offset the pale stucco exterior walls: so a kind of stark simplicity in and amid the daring, in and amid the instant strangeness to the look of the whole. (Did it come down from Mars?) When you’re inside, looking out, this curve of windows that fills up nearly the entire first-floor bay gives the effect of being in a modernist stained-glass chapel.

Advertisement

On either side of the living room and the kitchen — to achieve the two arms of the cross — the architect placed a reception room and a dining room. Except that he did one brilliant thing more: He elongated both arms of his cross by designing a carriage entry on one end and a screened porch on the far other, just feet from the sloping bank of the Kankakee River. No photograph can capture that great stretch-out quality. For that, you must stand in front on the sidewalk, perhaps from across the street, as I used to do, leaning on my handlebars. Then you’ll get the full wide measure.

We lived five blocks north, at 230 South Harrison Avenue. The address of the Bradley is 701 South Harrison. In those five blocks, you got the economic demographics of a town of about 25,000 people, upper crust to middle strivers. Our house was up where the ordinary folk lived, close to the courthouse and the town’s shopping district, a rangy old three-story stucco that my barely middle-class parents rented for $75 a month. Down at the river, on the cluster of streets fringing what was then called Riverview Park, was where nearly all of the town’s wealthy lived. Kankakeeans still speak of it that way: “at the river.”

Immediately to the north of the carriage entry (where, incidentally, Wright also placed, or hid, the main entry) is the Bradley’s sister house. It’s known as the Warren R. Hickox House. Yes, two Frank Lloyd Wrights sitting side by side, in a little rust-belted and once-agricultural and long economically threatened but still-handsome Illinois town 60 miles south of downtown Chicago. The Hickox is smaller than the Bradley. It has always been a private residence. But the Bradley, now a Wright public site, is the sibling that takes your eye. It’s the one that pulls in Wright-goers off the interstate to take the tour.

The Bradley had a riverfront sitting area, a great hearth of Roman brick, a sleeping porch on the second floor. The Bradley had a separate staircase for the servants. The Bradley had five horse stalls and a kennel and a hayloft and a chauffeur’s quarters in the stable/carriage house in the rear. The Bradley had more than 100 art-glass windows and light screens. The Bradley had specially designed furniture, both freestanding and built-in pieces. The Bradley had a butler’s pantry and a first-floor dressing room. The Bradley had a front terrace with low walls that seemed to be reaching right out to the sidewalk. In a way, it was like some manor house out of the English Tudor countryside — in Kankakee, Illinois. Even the carriage house and stable were outsized in its creator’s imagination: 3,000 square feet, on two floors. (The main house is 6,000 square feet.)

In 1988, before the saving began, when many art objects in the house had been plundered, sold off piecemeal to antiques dealers and other speculators, when raccoons had been eating through the roof for several years, an agent for Barbra Streisand bid $176,000 at Christie’s auction house in Manhattan for a long, low, brass-handled desk table from the Bradley. The price hit more than twice the estimate.

Years before that, the Bradley had been converted into an inn called Yesteryear. This was 1953, five decades after its birth. Grand people dined in there, on white tablecloths and with pressed napkins. They were eating by candlelight on the other side of those glittering ribbon windows. I would have been a fourth grader at St. Patrick’s Elementary, which was one block over and three up from the Bradley. One of my classmates was Burma Mathews. She has long given tours at the Bradley as a volunteer docent. On one visit there, as I was awed again by the interior gleams and quarter-sawn-oak angularities and interflowing spaces, Burma and I, out of earshot of the other tour takers, whispered about what an egotistical jerk Wright could be. Then she said, “But look at this thing he made.”

Yes, take a look at it again. If the point to be stressed here is the feeling of utter horizontality, then what to make of that imposing and low-hanging and deep-eaved gable at the front, not quite in the center and projecting out toward the sidewalk? Doesn’t it wreck the effect? In a sense, yes, because no matter its lowness, it gives an undeniable vertical accent, even when you are standing 50 yards off and nearly gasping at the kind of north-south stretch-out Wright simultaneously achieved. So to experience the house for the first time is to imagine someone’s interior torment. It’s as if something schizoid was going on in him, some kind of unresolved artistic torture, as if teams of mules were pulling the house and the house’s creator in opposite directions. As if that creator sensed that he was almost there, to his next level of purity and abstraction, but that he couldn’t quite yet make it, couldn’t quite find it yet, couldn’t quite get over the transom of his own imagination.

The full getting-over wouldn’t happen until the following year, 1901, in the wealthy North Shore suburb of Highland Park, when Frank Lloyd Wright began designing the Ward W. Willits House. Architectural historians seem in general agreement that the Willits stands as the first unadulterated Prairie. Is it a greater house than the Bradley? No doubt. And yet the argument might be made that this house, in economically hanging-on Kankakee, is the far worthier study, because it’s the one that came just as the clock was closing in on 12.

In the middle years of the 19th century, a plowman out of the East named David Bradley, with a knack for tinkering with farm equipment, imported pig iron into Chicago, his new home. He worked at a foundry. He partnered with a man who made wagons and buggies, and eventually he bought out that man and gave the concern his own name. He invented something called the Diamond Breaker plow, which won prizes at the 1893 Chicago world’s fair, and he also did innovative things with horse-drawn manure spreaders. In 1895 his Chicago plant, needing room to grow, relocated downstate, to North Kankakee. In gratitude, the financially pressed city fathers changed North Kankakee’s name to Bradley City, and then the next year just to Bradley.

Bradley’s sons worked for him in the David Bradley Manufacturing Company, and the next generation did, too, and one of these grandchildren, apparently less striving, perhaps because of a lingering, lifelong infantile paralysis, was named B. Harley Bradley. (The B stood for Byron.) On January 6, 1897, in the town’s Episcopal church, 26-year-old B. Harley Bradley, who’d gone to Amherst College, married Anna M. Hickox, a native Kankakeean four years his senior. Anna and her brother, Warren Hickox Jr., had inherited from their recently deceased father (whose wealth was in the real estate and loan business) a wooded site at the river, bottom of South Harrison. Two families, the farm-implement Bradleys and the long-prominent Hickoxes, had joined, perhaps the closest thing Kankakee then had to aristocracy. Three years later, in the winter of 1900, Anna and her brother took a train to Oak Park and engaged Frank Lloyd Wright to build for them and their families adjoining if not quite equal-sized houses.

But something went wrong on the Bradley side, or maybe it was many somethings. B. Harley and Anna and their adopted daughter, Margaret, lived in the house that they’d named Glenlloyd for about 11 and a half years — from the spring of 1901 until fall of 1912. After B. Harley was dead, after he had shot himself through both temples one summer Monday morning in 1914 while still in his pajamas in a room at the La Salle Hotel in downtown Chicago, there were stories — in Chicago dailies and passed around orally in Kankakee — about a previous suicide try with ether, about the reemergence of polio, about “the mystery woman.”

Here is the basic narrative of what seems to have taken place, and at least some of it is documentable, in and amid the many conflicting news reports: The patriarch of the Bradleys, the one who’d started the company, had died in 1899, and afterward his descendants had tried to carry things on — until Sears, Roebuck & Company bought out the firm in 1910, keeping the name but otherwise wresting control, even if certain family members were allowed to stay on. Was there enough money to go around among the family heirs? It can’t be said precisely. What is known is that B. Harley’s finances began seriously to dwindle. In September 1912, he and his wife — whose name the house was in — deeded Glenlloyd to a wealthy Iowan named A.E. Cook. They did so in trade: for $1 and also 522 acres of Cook’s western Iowa holdings, which were vast. So B. Harley and Anna and their daughter — as well as his retired parents, who’d been living with them in the house at the river — moved to Onawa, Iowa, hoping to start anew.

But things didn’t work out in Iowa, and money pressures seem to be a lot of the reason why. Two years later, in July 1914, 43-year-old B. Harley left for Chicago on a business trip. The trip didn’t go well. At 3 o’clock on a Saturday morning, on hotel stationery, he wrote a letter to Anna in Onawa and essentially said he was going to do away with himself. “Dearest Anna, you perhaps don’t know that I love you and I am a coward to get out of it all and leave it up to you to make so good.” Toward the end he said, “I know you will expect me home on the 7:30 train and I am going to disappoint you just this once more. Forgive me if you can, and don’t forget that I love you.”

He posted the letter in a box later that morning. He’d already purchased a .32-caliber automatic pistol for $10 at a Loop sporting goods store. The letter arrived by train in Iowa on schedule, at 7:30 on Sunday night. Anna was waiting trackside with a horse and buggy, thinking her husband would step off. The death letter, in effect, stepped off instead. Terrified, she wired a family member in Chicago. Meanwhile, her husband, having been out for much of that day, came in at 10 o’clock in the evening, placed the revolver under his pillow, and went to bed. He awoke about 9 on Monday morning, lay thinking, propped himself up with two pillows, pulled the trigger. The shot blinded him.

Advertisement

Somewhat later, a maid at the La Salle, finding his room locked, sent for the house detective. The detective hoisted himself up and peered in through a window slit above the door. When the detective and the house doctor broke in, there he was, mortally wounded, strangely calm. “I have a few lucid hours left,” he reportedly said. “Send for a Tribune reporter.” The next morning, the Chicago Daily Tribune, wishing its readers to think it had an exclusive, put the story at the top of page 1, column 3: “Buys Death Gun With No Permit.” But the city’s other sheets were trying to own the story as well. In most of them, B. Harley’s quotes strain credulity. To the Tribune, he was able to speak in rounded paragraphs about coming to the city “expressly for the purpose of committing suicide. My health hasn’t been good and business reverses caused me to shoot myself.” Not to be outdone, another Chicago daily wrote: “ ‘Got a cigaret?’ the dying man said. But he was too weak to smoke. He lay quietly for a moment. Then a look of disgust came on his face. ‘To h——l with it,’ he muttered and became unconscious again.”

He lasted until 5 o’clock that afternoon. By then, Anna had received a wire that her husband was dying at the city’s St. Luke’s Hospital. With her 19-year-old daughter she rushed for the overnight 6 o’clock train, not knowing he was already dead by the time they’d boarded. The two arrived in time for the Tuesday morning inquest at a morgue on North Clark Street. The verdict: temporary insanity. “B. Harley Bradley Suicides” was the headline in the Kankakee Daily Republican, but only on page 11 in its first-day report. The paper had been occupied with the Interstate Fair taking place in Kankakee.

These headlines — in Chicago, in Kankakee, in western Iowa — came almost exactly a month ahead of some other (and much larger) headlines about the most savage and iconic event in the nearly century-long life of Frank Lloyd Wright, namely that noonday inferno rampage, on August 15, 1914, at his beloved home, Taliesin, in Spring Green, Wisconsin, by a servant gone berserk with his shingling hatchet. Seven people died in that still-inexplicable incident, including Wright’s mistress. Wright was not home.

But that was still weeks off at this point. In the Chicago papers, the front-page stories about B. Harley appeared on Tuesday, July 14, the day after his suicide. By the next day, the story was essentially over for Chicago readers, consigned to the inside pages, and by then, too, the question of a so-called mystery woman in the case had all but vanished, like the supposed mystery woman herself, who was said to have been in a Chicago boardinghouse, awaiting some kind of contact from B. Harley. That part of the story seemed to fall away pretty fast.

In Kankakee, on July 15, a story headlined “Death Letter of Love” ran on page 1, the headline sounding eerily similar in tone, if not in content, to some Taliesin headlines that would be appearing in “Extra! Extra!” afternoon editions one month later. Did Wright see any of the Chicago stories, and, if so, did he quickly connect B. Harley’s name? It can’t be said. There were no mentions of Wright’s name in the Chicago dailies in connection with the death, or at least none that could be found. But it seems possible, if not likely, that he would have seen at least one of the stories. He was in and out of the city in this period, working intensely on Midway Gardens, the South Side entertainment facility he designed near the Midway Plaisance.

Anna Bradley? She and her daughter and in-laws came back to Kankakee. The woman who’d grown up in privilege (as a schoolgirl, she’d been sent by her parents to Miss Bliss’ School for Girls in Rochester, New York) opened the Tea Room, on Court Street, in downtown Kankakee, where she did the cooking and lived above the store with her in-laws. (They later left town.) Anna lived in her hometown for another 24 years, a faithful communicant at her childhood church, until April 1938, when they buried her beside her husband, out at Mound Grove Cemetery. She had died at the modest home of her brother, Warren, who had been earlier forced to give up his fine Frank Lloyd Wright home down at the river. Yes, he, too, had lost his fortune.

Capsuling the next six and a half decades, up to the critical saving year of 2005: First came the Birdman (who had taken up the house from A.E. Cook, who, incidentally, himself later lost his fortune). That’s how Kankakee historians affectionately refer to him: the Birdman. His name was Joseph H. Dodson. He held the property for the next 34 years. For many years he’d been a member of the Chicago Board of Trade. But his first and last passion was for birds. At one point he served as president of the American Audubon Association. In Wright’s ornate stable, he began manufacturing Dodson Bird Houses, distributing them nationally. He published pamphlets with such titles as Your Bird Friends and How to Win Them. He planted trees and shrubs, put out dozens of birdbaths and feeders, bought suet by the carload. By his counting he had 300 or 400 species living with him and his wife, Edith, every spring and summer: robins, scarlet tanagers, orioles, cardinals, brown thrashers, warblers, flickers, rose-breasted grosbeaks, hummingbirds, juncos, wood thrushes, vireos. They were his surrogate children, turning the property sweet with song before daylight, but from other points of view (the neighbors’) infernal with noise. His Martin Apartment House, more than five feet high, had a ventilated attic and 90 “rooms” for his nesters. It was made of cypress and redwood with a bright copper roof. It was like a tiny Frank Lloyd Wright production.

At the height of a Kankakee summer, you could anchor a boat in the river opposite the landing dock of the B. Harley Bradley House and look through the tall trees and make out the peaks of the gables and imagine a one-acre aviary without walls. If the Birdman of Kankakee, wandering the grounds in a straw boater, in his dress shirt with sleeve garters, is said to have taken reasonable care of Frank Lloyd Wright’s near masterpiece, at least until the last years, he loved his birds far more, and apparently didn’t mind saying so.

He died at the property, which he had named Bird Lodge, in the fall of 1949. He was a widower of 87. Edith had died five years before, and after her death and before his own he had deeded the house to his secretary, Lida Nelis, who was almost three decades younger than he was, and who had long served him in the birdhouse-building business, and possibly other things, too. According to city records and collective memory, she lived in the house with her own spouse in the final year of the Birdman’s illness. Did she tend him in his dying? Was she cynically after his money when his mind may have been befogged? Was there more to the story than that of bird boss and loyal young secretary? The legends float.

Next, interim owners, a local car dealer and his wife, Ed and Alice Bergeron. Then, in January 1953, the transition to Yesteryear. The new proprietors were two men, in their middle and late 30s, who met in the military during World War II, where at least one of them had worked as a cook. Their names were Marvin Hammack and Ray Schimel. They ran a Colonial inn in St. Joseph, Michigan, and had been induced to come to Kankakee to repurpose Wright’s increasingly famous building. They liked going around in three-piece suits with tea roses in the lapels. They didn’t go around holding hands, but the citizenry knew about them, or thought it did. (In fact, they were a gay couple. These decades later, a family member expressed astonishment, and also gratitude, that Kankakee had seemed to accept them so quickly into its midst.) It was as if these cultivated gentlemen, known to be kind to neighborhood children, were giving Kankakee a fresh cut of class. Soon people were driving down from Chicago and even up from St. Louis to try the prime rib and steaks, the baked Indian pudding, the fudge pecan cake balls. For meals catering to businessmen at midday, the innkeepers set up what they called the Ballerina Room. Not an immediate hit.

Hammack and Schimel watched over the house for the next three decades, a difficult proposition when diners were coming in and out six days a week. (Sometimes they arrived in chartered buses.) And then the innkeepers got sick — cancer for the one, a condition akin to Parkinson’s for the other. They had property in Fort Lauderdale and had long wished to get out from under the daily grind and hard winters. The house was starting badly to show its age, and along with this had come declining reviews and a falloff of trade. In April 1984, after a year and a half of trying, the ill couple negotiated a sale with a local businessman and his out-of-state partner. Reportedly, only three pieces of Wright’s original furniture remained. Half a dozen colored glass ceiling screens and other custom furnishings had been recently stripped out and sold for cash.

There seemed new hope for the restaurant, but not even 10 months after acquiring it, the owners filed for bankruptcy. Still, they tried to keep the doors open. In March 1985, during the Friday lunch hour, Commonwealth Edison shut off the electricity. Six months later, a reporter for the Tribune drove down from Chicago and looked around and wrote that the B. Harley Bradley House had “deteriorated into a vacant, cold, and musty-smelling building,” with first, second, and third mortgage holders fighting among themselves. On the tables, brown and pink folded linen napkins stood upright between silverware furred with dust.

And then, in 1986, Stephen Small entered the frame, and there came the strangest turn of all. His family had long controlled a conglomerate called Mid America Media. Kankakee’s Daily Journal was one of its properties, which included broadcasting and print groups across several states. Forty-year-old Steve Small, who’d been a high executive in the company until its recent sale, tooled around town in a maroon Mercedes. He was a family man, a nice guy. He and his spouse intended a full restoration, starting with the caving-in roof.

But on September 2, 1987, with scaffolding up and the work underway, Small got lured from his own nearby home in the middle of the night. (The voice on the other end of the line told him the Bradley was being burglarized.) His captors, who were after a million dollars in ransom, put a stocking cap over his face and handcuffed him and drove him to a wooded area about 12 miles southeast of town, where they buried him alive beneath three feet of sandy earth, in a homemade box six feet by three feet. They gave him five candy bars, a jug of water, a flashlight, a package of gum, and another light hooked up to two car batteries. For his supposed breathing, they rigged a length of PVC plumbing pipe that stuck up through the top of the box and the sand like a periscope.

The PVC pipe didn’t work. The media heir suffocated to death as he apparently kept trying with muffled screams to jam at the ceiling of his shallow grave. At the trial, the medical examiner testified that he’d probably survived for no more than three or four hours.

About 72 hours after Small had been taken, the police and the FBI were led to the box and his body. By then they had the kidnappers in custody: a 30-year-old local cocaine trafficker and his 26-year-old girlfriend, who’d been a cashier at Kroger. (The ransom demands had been haplessly made from pay phones at local gas stations; the police had little trouble tracing them.) The nationally covered trial was in the Kankakee County Courthouse, and Frank Lloyd Wright’s name and house came up in some of the stories. The trial didn’t quite last two weeks, and on the first day the state wheeled into the courtroom, and kept there, the plywood box that the ringleader had built in his garage. (His name was Daniel Edwards, and he had sealed the seams with white caulking, then had left in the trash a pair of gloves with the caulking on them.) The jury listened to a recording of Small’s voice from his grave; it also saw a videotape of his body. Edwards was convicted of first-degree murder; a few days afterward he got the death penalty. His accomplice girlfriend, Nancy Rish, tried separately, got life. (In 2003, the Governor George Ryan, who was from Kankakee, commuted all death row sentences to life imprisonment.)

In 1990, Frank Lloyd Wright’s hard-luck house, which by now, at least to some, was an object of almost macabre curiosity, came into the hands of its ninth set of owners: a firm of Kankakee lawyers and an architect. They turned the Bradley into offices, doing what they could to restore things, even if their agenda wasn’t necessarily that of Wright purists. Their restorations didn’t include the stable/carriage house, and when the building seemed about to cave in on itself, they applied for a permit to demolish it. “Wrong on Wright,” the Daily Journal editorialized in 2001. “Kankakee has always seemed to be a community that has struggled with its past.”

Maybe that sentence threw down the gauntlet. A few years later, in 2005, a vice president of a Chicago acoustics design firm, along with his wife, acquired the Bradley. It was as if Gaines and Sharon Hall were the true inheritors at last. Relying on Wright’s original drawings, the Halls set to work rescuing the entire property, but first the stable. In the house they painted the walls in shades of mustard and green and deep burgundy, using a technique called scumbling, popular at the time the Bradley was built. (You soften the colors by applying thin coats, as many as four, ending up with a delicate mottling effect.) The old house, against every reversal, every injury of time and weather, every gossip and bad headline, was coming back, if not to what it once was, then to something trying to honor what it once had been.

Except not quite: fire. On a Friday night in early January 2006, after the Halls had been living in the Bradley for a year, with the work going on around them, the couple were having dinner with friends at the Kankakee Country Club, which is in the river district, about five minutes from the house. An assistant manager came over and whispered into Gaines Hall’s ear: “Sir, your house is on fire.” He jumped up from the table and ran to the parking lot. Sharon Hall said to the server: “What’s going on? Where did my husband go?” Someone drove her to the house, where ladder trucks were shooting towers of water onto her home’s new roof, with the sky weirdly lit up in arc lights.

The fire had started in the attic near or in an air-conditioning unit — which, of course, wasn’t on in January — and had begun to work its way down the chimney, through the master bedroom on the second floor. If the fire had come a few hours later, the Halls might have died in their bed. Sharon Hall found her husband at the ring of the shooting sprays. He was shaking his head while the firemen put out the last flames. She said, “That’s it, I’m done.” Her husband turned to her and said, “OK, but will you take me with you?”

Advertisement

They were out 14 months (the damage was said to be $200,000), but started in again, and over the next four years brought the house up to a kind of shine and artistic integrity it had almost never known, except at the start of a previous century. These days the B. Harley Bradley House, which has been on the National Register of Historic Places since 1986, is under the stewardship of a nonprofit organization called Wright in Kankakee. It takes extremely proud care.

I’ve been on the tour with Kankakee historians and with my old first-grade girlfriend, Burma Mathews. I’ve been through the Bradley’s 13 light-refracting rooms with Gaines Hall, retired now from his Chicago design practice and also from a late-life stint as a professor and associate dean at the University of Illinois. Some days it seems quiet as a church in there. “This is the house that changed the face of American architecture,” Hall likes to say. If the sentence isn’t literally true, it’s true enough. Leave it where it lays.

Comments are closed.