The ongoing manure situation says a great deal about what really matters to Ken Dunn. Since 1972, he has run a nonprofit organization called the Resource Center, and for 17 years one branch of the center held the contract for removing manure from the stables used by the Chicago Police Department. Dunn kept the contract for so long not because it paid off particularly well but because it helped bolster another of the Resource Center's main activities, making compost. The center uses restaurant kitchen trimmings, waste materials from landscaping companies, and other natural detritus to create organic growing material, but-and centuries of experience prove this-for rich, delicious-to-worms compost, nothing beats . . . well, you know.

For a long time, the police horses had been providing the Resource Center with more than 100 cubic yards of manure every month, a sizable contribution to the more than 3,000 cubic yards of compost the center produces each year for use in its organic farms and for reselling to gardeners. But three years ago, a more conventional waste removal company underbid the Resource Center for the relatively small job-a change, Dunn says, that saved the city about $40 a month.

And the thing about Ken Dunn is, he doesn't mind competition, or seeing the city look after its resources, or even lost revenue. What he minds, he says, is that the company that took over the job started trucking the manure to a landfill, rather than turning it into the plant-feeding gold that it was meant to be.

In other words, some perfectly good waste was going to waste, an affront to what is perhaps Dunn's main driving conviction. In all his endeavors, he seeks to promote a "sustainable" society-that is, one that can continue indefinitely "without diminishing the opportunity of future societies to take pleasure from our planet," he says. This means not taking more than our fair share. It means, to put it in kindergarten terms, putting things back where you found them.

His near-religious pursuit of this ideal-this living in close accord with his deepest personal convictions-is not without costs and consequences. After the Resource Center lost the contract, he felt compelled to speak with decision makers in the city's Department of the Environment. Those conversations did not go well, and eventually damaged some longtime friendships. But the rewards of his well-examined life-the pleasures, even-make some sacrifices well worth the effort.

Dunn's noble aims are not what make him the smartest man in Chicago. Many environmentalists, activists, and optimists share his basic goals. But few have undertaken advanced study in philosophy at the University of Chicago. Fewer still have successfully navigated the city's bureaucracy, persuading it to hand over large pieces of empty land, free, to raise healthful produce for the benefit of the citizenry. And fewer still spend their days operating a ten-wheel diesel truck, the cab of which serves as their main place of business. Dunn embodies a sort of American ideal of intelligence, an extraordinary melding of farmer and philosopher, of city contractor and iconoclast. He is a very, very smart man.

"What I like about Ken is his holistic approach to the challenges we face," says Saddhu Johnson, a special assistant to Mayor Richard M. Daley and the city's new "greening guru." "He is visionary. He is innovative, and he has the passion and enthusiasm and energy to implement the vision."

He is tenacious, too. When the manure contract comes due later this year, he says, he will underbid his competitor, though it will make the Resource Center's profit razor thin. He will do it because it is the right thing to do. Because although it is horseshit, in some senses it is our horseshit, owned by the citizens of Chicago, and it ought to be put to our good use.

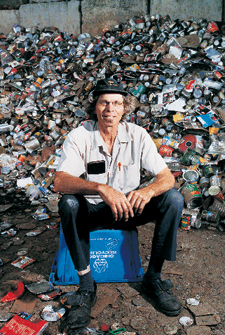

If forced to select a favorite philosopher, Dunn chooses Plato, for reasons that quickly become clear. "Plato's Republic is about how society could be arranged to accomplish the good, the true, and the beautiful," says Dunn, a wiry, tall, chisel-handsome 61-year-old who looks about 47. Discussing the Republic is not all that unusual for Dunn: He has a thoughtful manner, and completed his coursework for a Ph.D. in philosophy at the University of Chicago some years back (his dissertation on resources, labor, and discontent remains unfinished). But on this bright spring afternoon, here at the Resource Center's three-acre South Side recycling yard on East 70th Street, Dunn is talking Plato while working the gears of his enormous truck, backing it deftly into position to pick up a load of compost. His take on Plato's definition of harmony is almost drowned out by the thrum of the engine. Unusual.

The truck is a ten-wheel diesel Freightliner, a bone-rattling monster with a hydraulic lift on the back that can raise and lower enormous metal containers of compost, or newspaper, or whatever Dunn might need to move from place to place. The cab, cluttered with rags, tools, and papers, essentially serves as his office. His cell phone rarely stops ringing.

Surrounded by trees, the compound is a shimmering landscape of mountains of aluminum and tin cans, cardboard, and green and white glass. Seagulls soar above the yard, their cries a background to the sounds of glass and metal being dumped and moved. The glass that comes in, hauled by some of the Resource Center's fleet of 23 vehicles, is sorted and eventually sold to a glass factory, to be remade into bottles. The tin and steel are sold to a steel mill; the aluminum is sold to an aluminum mill. "Recycling is a very simple and straightforward thing," Dunn says. "We can make all the things we use out of virgin material, extracting from the planet, or we can make everything from materials already in use." Dunn rejects the critics of recycling who assert that it takes more energy to collect and reprocess materials than to create new ones-but he believes that recycling, like many things, needs to be practiced more efficiently.

This South Side yard is one of the Resource Center's two main locations, and here local residents can donate materials or turn in aluminum cans for a voucher that can be redeemed at a neighborhood store. At this location and at the headquarters yard at East 135th Place, the Resource Center processes about 500 tons of material every week-a tiny fraction of the material the city discards and, for the most part, sends to landfills.

Recycling is just one of the Resource Center's activities. The organization's seven units have different functions, but they are all engaged in the pursuit of Dunn's sustainable society. A mobile recycling program serves all the Chicago Housing Authority sites in the city, buying materials from residents and transporting them to the proper recycling facilities. Another unit moves perishable items such as goods in slightly dented cans and day-old bread to food programs that can use them.

The Blackstone Bicycle Works program, at 6100 South Blackstone Avenue, repairs bikes of all shapes and sizes and sells them on the cheap; besides using its profits for social programs, the repair shop also teaches youths in the neighborhood how to fix and customize their bicycles. (An April 2001 fire at the facility forced the program to operate out of on-site trailers, but construction on a new facility has begun.) And the Creative Reuse Warehouse, a combination retail store and repository of "overruns, rejects, and byproducts that business and industry treat as ‘waste,'" according to the Resource Center Web site, has become a favorite stop among artists and schoolteachers, who can acquire paper and crafts materials for a fraction of their retail cost. Donors can get a tax deduction. (The warehouse was forced to relocate because of expansion by the University of Illinois at Chicago and currently operates out of the Resource Center headquarters.)

These various operations employ 28 people full time, supplemented by a volunteer crew of close to 100. The full-timers, many of whom have been with the center for more than two decades, receive health insurance and a living wage. The total budget for the Resource Center is $2 million to $3 million annually, a sum that is raised from grants, donations, and revenue. "Even though I am the chief officer, I'm somewhat in the middle of it in terms of salaries," Dunn says, before leaping up several feet and pulling himself to the edge of the tall container, now filled with compost, on the back of his truck. "I can get the pleasure of seeing everything and having some fun experiments, but don't get the most money."

Dunn would be paid a great deal more if he were compensated for each of the functions he performs. On the way to the yard at 70th Street, he had noticed a decrease in pressure on the left side of his truck's air suspension. So while the compost was being loaded, he pulled a pocket tool set out of his trousers, detached the faulty line, and patched into the system on the right side. The Resource Center bought the truck new in 2000, and as Dunn springs back into the cab, he says he is glad he put that redundancy in the specs when he bought the vehicle.

And then it's back to Plato.

"He mentions that you have to watch out for two things to have a stable society," Dunn says, shifting gears and pulling out of the yard. "You want to avoid unequal power and riches among individuals, because that produces jealousy. And you also want to eliminate haves and have-nots, both with things of value and with freedoms. And I would say that our society is unsustainable because of the power relations we have going. Some religions would like to dominate or eliminate other religions, some philosophies would like to eliminate other philosophies, but I think that individuals on the planet should have equal rights or power and authority over their own person-an equal right to benefit from their activity."

Undoubtedly the most visible of the Resource Center's activities-and, in some ways, the aspect of the organization that most thoroughly demonstrates Dunn's particular genius for navigating city bureaucracy while promoting sustainability-has been City Farm, a series of organic gardens planted in vacant city lots. To create ideal growing conditions at each site, workers truck in a layer of clay to keep any existing contaminants from reaching the plants, then pile on ten inches of manure and a foot or two of compost and mulch. The first garden was planted in the early nineties.

Currently the largest City Farm plot is located in the triangle of land at the intersection of Clybourn Avenue and Division Street, a high-traffic area between the new Dominick's-anchored shopping center and the remains of the Cabrini-Green housing complex. The farm is an appealing oasis of greenery and lush order in an area that, despite ongoing development, remains somewhat bleak. Dunn and his colleagues started the Clybourn Avenue site in 2002, and next year their land will be halved. And after that growing season is over, they will have to leave entirely, because the city plans to develop the parcel. It's all by design, though: By negotiated agreement, the city will not uproot a City Farm site during growing season, but when it's time to go, they go.

Dunn acknowledges that urban agriculture has the most potential for spreading the word about sustainability. "You don't have to dislike factory farming to recognize you've got something when you can take food waste to enrich soil to produce food and keep the cycle going," he says. And you don't have to care about any of that to know a good tomato when you bite into it.

The several dozen varieties of tomatoes grown in the City Farm's plots serve as its greatest ambassadors, in part because most tomatoes sold in grocery stores do not compare. "The tomato has become a tennis ball," Dunn says. "They get harvested all at once by a mechanical machine. They bounce around in the machine and into their transport hoppers like tennis balls. They can undergo shipping, refrigeration, and storage, and voilà! there's your tomato. Except that it doesn't taste anything like a real tomato. And its nutritional value is not anything like that of a good tomato."

Dunn's partner, Kristine Greiber, who serves as the program director of City Farm, spends the bulk of her time here at Division and Clybourn. She is easy to spot as she zips around town in a bright red Honda Insight, a high-mileage hybrid vehicle, taking along the couple's three-year-old son, Soren (although Dunn is an admirer of Kierkegaard's work, he insists that he and Kristine just liked the sound of the name). Kristine, 38, who grew up on a small dairy farm outside Madison, Wisconsin, met Dunn when she was a graduate student at the School of the Art Institute and began volunteering at the Creative Reuse Warehouse. She was drawn to Ken, she says, simply because he was "faster, stronger, and smarter than all the other guys around."

The operation attracts a number of volunteers-David Banga, for example, is in his second season working on the farm. A ceramic artist with a master's degree from the University of Utah, Banga moved to Chicago with the somewhat misplaced hope to learn about farming. "I didn't think I would be able to," he says. "At first I figured I would be working for the park district taking care of whatever they would have in the parks. I was lucky to run into these people."

Banga became a full-time employee last year. On a quick walk around the grounds this past spring, he pointed out seedlings of radishes, melons, pumpkins, and tomatoes. A number of salad greens-arugula, claytonia, mâche, mustard greens, and spinach among them-he noted, are planted on the northern edge of the plot to benefit from a microclimate created where a building adjoins the property along its northern edge. "The sun hits right on this white wall and reflects a bit, and if you go anywhere near the wall you can really feel the extra heat," Banga says. "And it radiates probably for another two hours after the sun goes down. With winegrowing, [the microclimates] have mostly to do with hills and valleys. Here it's buildings in the city."

That morning, Banga had sold five pounds of lettuce, at nine dollars a pound, to Topolobampo and Frontera Grill, perhaps the most prominent of the restaurants the farm supplies. The chef of the River North establishments, Rick Bayless, is dedicated to buying local goods, including oak for its fireplaces (from pallets the Resource Center has broken down) and a variety of organic lettuces. But above all he buys tomatoes-about 6,000 pounds of them each year. And like other customers past and present (including chefs from the Ritz-Carlton, North Pond, Lula Cafe, and Scoozi!), Bayless insists that quality is the motivator. "That's how we got started with them," Bayless says. "We were looking for freshness and flavor, and they gave it to us."

Bayless shares Dunn's manic energy and his drive to create something better, but he is careful to note where the similarities between them end. "I'm not a fighter. He's a fighter. I'm an entrepreneur," Bayless says. "The guy is one of the most amazing visionaries who have ever lived in this town. But I have seen him crawling around in dumpsters. And it would be a very special day to find me crawling around in our dumpsters."

Ken Dunn's hands are perpetually dirty, and they have been for a long time. He grew up on his family's farm in a Mennonite community in west Kansas, a place where he "absorbed the values required to live an ethical life," he says. The community essentially governed itself through a group of elders whose focus was to prescribe the right and proper care of plants and animals. The Dunn family's main crop was wheat, with a healthy chunk of alfalfa and sorghum. They also owned a few hundred head of beef cattle, which they fattened for consumption in the great steak houses of Wichita. "We had a very good thing going with one restaurant," Dunn recalls. "In their advertising, they once used a slogan: ‘You can be sure our beef is Dunn right.'" All told, the farm had close to 500 acres.

Dunn's mother died when he was three, leaving him to be raised by his father. When Dunn was about 12, his father suffered a severe heart attack, and Dunn and his brother, a year older, began participating in the farm's major decisions. Seeking to increase productivity, the brothers began moving toward factory farming methods, buying larger equipment and using chemicals. "What we discovered was that, just below the layer we used to till, was developing a compaction layer. And the county agent said, ‘Well, you are going to have to start subsoiling,' which is using a tool that loosens the soil down to 36 inches deep. That's recommended every few years, but whenever you need to loosen soil down to that depth you need a bigger tractor. You get your bigger tractor so you can do this loosening, and then you have to keep doing it because that tractor weighs more so you have to do it more often. And once you start using chemicals to battle your enemies, then you are starting a constant battle. Factory farming has these cycles that are self-perpetuating."

Dunn realized that what he was doing with the family's farm was not good for the soil or the crops, a notion that led him to larger questions and eventually to Bethel College, a small school near Wichita associated with the Mennonite Church. He played football there and graduated with a degree in psychology and philosophy in 1964. Fresh out of school, he "decided that the world was so enamored of technology and corrupted by forces that make people make the wrong decisions" that he ought to seek out a simpler society. His choice was the Peace Corps, and an assignment "totally in the backwoods" of the Upper Amazon of Brazil, where, he says, he felt he could begin to "build a life based on values."

Of course, to be an effective Peace Corps volunteer in Brazil, you have to learn Portuguese. So he did. Dunn was in Brazil for three years, developing agriculture and lumber programs, riding his motorcycle, and spending most of his time with a native Amazonian, "sort of a shaman in their tradition."

Still, Dunn felt that he had much to learn about life. He returned to the United States to "study with the best," seeking out the widely acclaimed University of Chicago professor Richard McKeon. "He was regarded as one of the few living philosophers," Dunn recalls. "He was taking philosophy back to the notion that it was a systematic way of looking at problems and coming up with solutions. He maintained that there are just a few great ideas and a variety of methods which you can use to tinker with those ideas to adapt them to different circumstances. My philosophy training was in how to make decisions to impact society in the right direction."

Dunn finished his M.A. in 1972 and completed the coursework for his Ph.D. in 1976, but he found himself distracted by the outside world-even more so, perhaps, than the average procrastinating doctoral candidate. "There was just a shock of seeing Chicago, with all of its inequalities and communities with so much vacant space," he recalls. "I thought, I cannot live here unless there is a way to improve on this. With so many things needing to be done and so many people needing something to do, why weren't they connecting?"

And from that question grew the Resource Center: Dunn had noticed a group of men habitually sitting at the edge of a vacant lot next to a liquor store. Every day they would scrounge up enough money to buy a bottle, then drink it, and finally toss the bottle into the empty lot next to the store-turning the space into a dangerous, glinting sea of glass. Dunn approached the men and proposed that they collect the bottles and give them to him. Dunn sold the bottles and split the money with the drinkers, closing the circle (and cleaning up the lot).

"That is kind of the context of the Resource Center," he says. "Instead of making our society better through religious conversion or political change-systems which are entrenched with their powers-why not make one's activity that which is overlooked by industry and politicians? Look at resources that are possibly of no value and see if there can be an ingenious relating of the wasted human capital with the wasted material capital. If you are creative you can find ways of taking wasted human potential and engaging it with wasted resources."

Dunn steers his lumbering truck through a South Side neighborhood known simply as The Bush. Tucked just north of the mouth of the Calumet River between 79th and 86th streets, the area has plenty of boarded-up buildings and small homes. Eight or nine people, some with shovels, are standing at one end of a vacant corner lot where a dim rectangle of cement, the skeletal outline of a long-gone building's foundation, nudges up through the grass and weeds.

Dunn skillfully swings the truck left, then right, finally backing over the curb and into the middle of the lot. Then he dumps a large pile of dark compost into the middle of an area delineated with twine. This shipment is part of a program Dunn has negotiated with members of the City Council. The Resource Center has donated ten cubic yards of compost to each alderman for greening projects in their wards. In this instance, those ten are supplemented by 15 more that have been bought from him by Green Corps, a program of the Department of the Environment.

Diana Ramirez, a 48-year-old woman who lives in the neighborhood, has volunteered to help create the garden. To her, the giant load of compost isn't some sort of save-the-earth act of goodness. It's going to make the summer a lot more convenient. "I hate to say this," she says, rolling up her sleeves, "but we have to go to Indiana to buy vegetables. There's nothing around here but liquor stores and candy stores."

Karen Roothaan, a community organizer who is supervising the placement of the compost, introduces her teenage daughter. "This is Ken Dunn," she says to her daughter, who is interested in an internship with the Resource Center. "The compost king." (Later, talking about the manure deficit, Dunn will point out that the center's compost "did derive its excellence from its variety of materials.")

Dunn takes a few minutes to chat with the volunteers, who are busily spreading the rich dirt. And then he is back in the truck, headed again to the lot at 70th Street to pick up a load of paper for recycling.

"Today those people are in contact with the ground and enjoying real things," Dunn says, shifting gears and looking for the highway. "There is so much business involved in evaluating and reflecting on and relating to things that are not real. Most people share values by talking about the football game. But these are values of planting and getting your hands dirty in the soil together as a local community. It's exciting."

Smart, too.