EDITOR’S NOTE: A Feb. 11, 2008, column by a campus reporter about Lavine’s use of anonymous sources in his column in the alumni magazine sparked controversy at the school. On Feb. 19, members of the Medill faculty released a statement expressing concern and demanding answers. The next day, in an e-mail to students and faculty, Lavine apologized for his "poor judgment" in quoting unnamed sources.

Dean Lavine’s opinion about turning out journalism students the old-fashioned way: "It is immoral."

It was a bare-knuckled accusation that seemed suited more for a blue-collar saloon in the bungalow belt than the ivied Evanston campus of Northwestern University. “You lied to me!” the graduate student angrily told John Lavine, the dean of the Medill School of Journalism. “I came here to learn to be a writer,” the student said, explaining that he had chosen Northwestern—and forked over more than $40,000 in annual tuition—because he wanted to hone a flair for writing that would land him at a publication like The New York Times. “But you’re having us do all this video stuff. I didn’t come here for that.”

Lavine scoffed at the notion that he had lied to anyone. At that meeting with disgruntled students during the summer quarter of 2006, he insisted he was acting in the best interests of their budding careers. “It would be unethical for us to educate you to only be able to write,” he said. “It would be like sending you out with your left arm and your right leg tied behind your back.”

The rancor could not have come as much of a surprise. After taking over as the leader of Medill earlier that year, the new dean had vowed to “blow up” the old curriculum at what has long been considered one of the best journalism schools in the country. He declared that students needed to be immersed in “new media”—Web sites, videos, filmstrips, video games, and podcasts. And the new curriculum would emphasize an understanding of “audience”—who the customers are, what they want, how to reach them. The concept of marketing—widely disdained by ink-in-their-veins journalists—would assume a key role in the teaching program.

Lavine’s revolution has set off a year of skirmishing and argument both in Evanston and among the wider community of well-placed alums, and the commotion is likely to culminate this fall when the new curriculum takes full effect. Whatever the merits of the changes, the angst mirrors the sense of uncertainty, even downright fear, in the real world of newspapers and other “old media” outlets. Circulation and advertising have been plummeting at big-city newspapers, owing to the Internet and changing tastes, particularly among the young. The Los Angeles Times, for example, lost about 25 percent of its circulation between 1996 and 2006. The New York Times and Tribune Company, among others, have eliminated hundreds of jobs. It is not impossible to find people making brave predictions about a rosier future for newspapers, but Wall Street has been betting against it. Stock prices at many large newspaper companies are half what they were a few years ago.

Against this backdrop, Dean Lavine argues, it is worse than wrongheaded to continue to turn out journalism students the old-fashioned way, preparing them for disappearing jobs in print publications and giving them little knowledge of the changing demands of consumers. “It is immoral,” Lavine says.

But some faculty members object to training future journalists to be marketers. “Marketing can get dangerously close to pandering,” says a Medill professor who declined to be identified, citing concerns for job security. “I don’t want my students to write to the interests of a particular audience. I simply want them to be competent journalists.”

George Beres, who graduated from Medill in 1955, and later taught in the school and worked as the sports information director, fears a blurring of the line between public relations and journalism. “This business of ‘understanding the audience’ is about manipulating the audience,” he says. He worries that when journalists concentrate on “making their product attractive to the customer,” they might “evade or color subject matter to avoid making it distasteful to the customers.” In Beres’s view, professional journalism has already strayed too far in that direction. One of the consequences, as he sees it, was a failure to investigate the motives and rationale for invading Iraq, especially in the early days of the war, when patriotism among “customers” was at such a high level.

If postings on the Internet are any measure, plenty of students at Medill are furious about the changes. “How can I possibly be going to ‘the best journalism school in the country’ if we don’t learn writing,” reads one recent posting.

Lavine says that he sometimes feels that his critics are simply shooting the messenger. “Young people don’t understand that if a paper doesn’t sell, it dies.”

* * *

Photograph: Anna Knott

Old school: The magazine department is based in the 1899 Fisk Hall. |

Northwestern has long stood as a grande dame of American journalism education. Since it began as a department in 1921, Medill has built a national reputation as a top training ground for aspiring journalists, emphasizing traditional reporting and newswriting, and churning out graduates capable of walking into a newsroom ready to cover a fire, a big crime, or a political squabble. It has produced a long list of stars: Howard Tyner, the former editor of the Chicago Tribune; the syndicated columnist Georgie Anne Geyer; the former New York Times sports columnist Ira Berkow; the sportscaster Brent Musburger; and, on the advertising side, Scott Bergren, who is now the president of Pizza Hut.

And with its illustrious reputation, Medill continues to draw many of the best and the brightest aspiring journalists from around the nation. One of them is Sarah Sumadi, a San Antonio native who chose Northwestern over Dartmouth, even though the Ivy League school offered her a better financial package. “I came for Medill,” says Sumadi, in a quiet voice that hints at some second-guessing. “It’s unfair to judge the changes too early, but it’s been rocky so far.” The training in technology has eaten up time that could have been spent developing skills in reporting and writing, and she’s skittish about so much emphasis on discerning the audience. “I’m a little worried about this idea that we’re supposed to be focusing on ‘the consumer,’ like news is just another product to be sold.”

The changes at Medill are being closely watched by schools across the country. “Any time there is an innovation at Northwestern” and a handful of other prestigious journalism schools, “people sit up and take notice,” says Roy Peter Clark, a senior scholar at the Poynter Institute, a Florida-based think tank for journalists.

Columbia University’s journalism school—usually regarded among the top with Medill—has also been re-evaluating its curriculum, but it won’t follow the new direction at Medill, according to Columbia dean Nicholas Lemann, the prizewinning author and writer for The New Yorker. “It’s not going to happen at our school,” he says of the emphasis on marketing, “not on my watch.” He acknowledges that classes at Columbia have become more “Webbie” in response to employer demands that students have technical skills. Columbia has also recently revamped its curriculum, with tracks that go deeper into subject matter, so that graduates emerge with a firm grasp of specific disciplines, such as the law.

But Lemann said Columbia would continue to follow the guidelines set down by Joseph Pulitzer, who endowed the New York journalism school and laid out a manifesto on how it should be run. “Business instruction of any sort,” Pulitzer declared in 1904, “should not, would not and must not form any part of the work of the college of journalism.”

Of course, in Pulitzer’s day, readers and advertisers were not defecting to Craigslist and other Internet sites. The journalism school was named for Joseph Medill, the former editor of the Chicago Tribune, and he gave it his own motto: “Follow the line of common sense.”

* * *

Before Lavine’s arrival, a student at Medill could concentrate on, say, print journalism and pay scarcely any attention to emerging technologies or marketing techniques. The staple of a Medill education was the ability to identify what was newsworthy and write a story about it, mastering the basics of who, what, where, when, and how. Students were drilled in one of the bedrock principles of American journalism: that a wall existed between the editorial side of a publication and the business side.

Under Medill’s new system, all courses are taught “across platforms,” so that students must learn storytelling in video and audio media, as well as in print. The aspiring journalists are also required to discover more about their audience and what those people want to consume. In one basic reporting class, students operate out of a storefront newsroom in Rogers Park, fanning out across the neighborhood to ask people what issues are important to them—much as a focus group might. The students gather demographic information on the community, then crunch numbers to better understand their potential “customers.” It is a much more intensive effort to “understand audience” than Medill has traditionally done.

“The increasing challenge for journalists is how to get their work read, watched, or listened to,” Lavine says. “We teach students how to gain insights into the people they are trying to reach—what their lives are like, what kinds of news and information are relevant to them, what they need to know.”

As it turned out, Medill and Lavine were well positioned to teach that kind of demographic research. Medill has long offered a master’s degree with an emphasis on advertising. About 15 years ago, that track was incorporated into the new Integrated Marketing Communications program, which includes emphasis on public relations and other marketing-oriented skills, and offers a master’s degree. IMC has coexisted somewhat uncomfortably with the journalism side at Medill since then. (The graduate school includes about 350 students working toward master’s degrees in print, broadcasting, magazine publishing, new media, or marketing over 18 or so months; about 650 undergraduates study for four years to earn a bachelor’s degree in journalism.)

Until Lavine arrived, the IMC wing operated as a separate faculty. His mission has been to “integrate” the two sides. Some on the journalism side, with a measure of arrogance, regarded their own mission as a noble quest for truth and the marketing side as a sellout to corporate interests. Not surprisingly, some on the IMC side chafed at being seen as second-class citizens and even considered breaking away from Medill and moving to another school within the university, perhaps the Kellogg School of Management.

Lavine boosted the profile of IMC. It now gets equal billing on the school’s Web site, and the site has dropped the phrase “school of journalism” and goes simply by Medill. (The official name is still the Medill School of Journalism, but Lavine has suggested that a new name might reflect some of the marketing training done at the school. Such a move would require approval by the board of trustees.)

* * *

Photography: Kim Thornton

New school: The McCormick Tribune Center, completed in 2002, houses the broadcasting and new-media facilities.

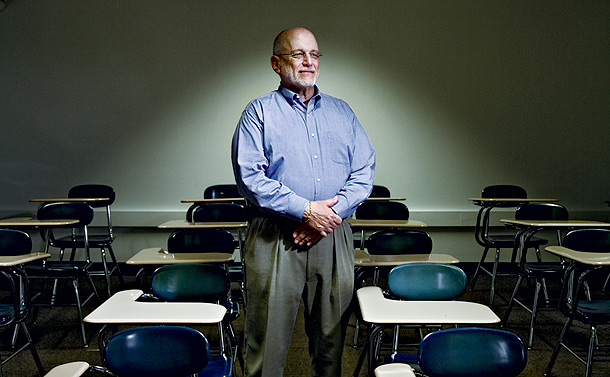

At 66, Lavine looks the part of a grisly desk editor at a big-city newspaper: bald, stubbly beard, rimless glasses, and no shortage of attitude. He comes off as exceedingly bright and just as cocksure. In 2005, after internal and external reviews found Medill needed to make dramatic changes to keep up with the transformations in the media landscape, Lavine, whose specialty is media strategy, was asked to provide his prediction for the future. After he did so, he was offered the position of dean by the provost, Lawrence Dumas. “He was seen as the change agent,” says Abe Peck, a professor who served on the original curriculum review committee.

But Lavine is not cut from the traditional mold of people who have led Medill: journalists rooted in the editorial side of nationally prominent media, immersed in the culture of news, but not focused on corporate financial strategies. In contrast, Lavine comes from the business side, having owned a chain of small-town newspapers in Wisconsin, where he grew acutely familiar with the marketplace. A native of Superior, Wisconsin, he bought his first paper, the Chippewa Herald-Telegram, at age 23. He went on to own four dailies and four weeklies and later expanded his business to documentary filmmaking and medical publishing.

After teaching at the University of Minnesota, he came to Northwestern in 1989 and founded the Newspaper Management Center, now called the Media Management Center (he has sold off his newspaper holdings). A joint venture between Medill and the Kellogg School, the Media Management Center trains graduate students to run media outlets. The center does not confer degrees, though professionals returning for training can receive a certificate. He later started the Readership Institute, which researches the views and tastes of news consumers, largely through surveys and focus groups. Today, Medill students draw heavily on the research of the Readership Institute to learn about catering to an audience. Among the findings of the institute: Today’s consumers want “news they can use” and information that is relevant to their own lives and communities.

Lavine acknowledges the criticism among some faculty and students. “They’re upset with change. I understand that. My response is, If you really care about journalism, you can’t ignore the reality. Doing more of what we’ve done doesn’t work.”

The Media Management Center and the Readership Institute also hire themselves out as consultants for news businesses—a source of money for Northwestern. The Dayton Daily News employed the Readership Institute, and Jana Collier, the paper’s managing editor, says the research was helpful in reminding editors, writers, and photographers to focus on the desires of readers. “In all honesty, journalism has been a lot more about us than it’s been about our customers,” says Collier. She adds that if Northwestern is teaching students to learn more about readers’ interests, they are far ahead of the game. “In general, journalism schools are not producing what we need for the future,” says Collier. Journalists have “got to know more than how to write a lead. They need to understand our audience.”

* * *

If the new technological demands pose challenges for students, it’s an even higher hill to climb for teachers, especially among those older than the generation born with a mouse in their hands. Eric Ferkenhoff, a lecturer who has 15 years of experience as a writer and reporter, including a stint at the Chicago Tribune, says the tech-savvy environment at Medill means that “instructors are playing catch-up at the same time the students are playing catch-up.” He lauds the goal of preparing students for whatever technological demands they face on the job. But he says a great deal of material has been crammed into classes. “It’s as if you were teaching basic math and then shoved in some calculus and statistics,” he says. “Some of the people aren’t going to learn two plus two. And that’s the danger here.

Ferkenhoff counts himself a supporter of the dean’s new direction and says most students and faculty members are coming around to it—“not to say they’re falling in love with it.” Few teachers would argue that it’s not going to take a while to work out the bugs.

Nomann Merchant, a junior, agrees that the problems will eventually be fixed. But the problem for students who are here now: They’re here now. “It’s a lot to ask a professor who has taught newspapers for 25 years to suddenly teach new media,” says Merchant. “Eventually, things will work out. But we’re paying $45,000 a year now. So there is some bitterness.” (The university does not disclose the number of applicants for Medill. But Mary Nesbitt, an associate dean, described the situation as “healthy.”)

In his office on the second floor of Fisk Hall—where he sits at a desk with a three-screened computer—the dean cheerfully admits some missteps. He says he tried his own blog, which flopped, and started a Medill bulletin board, which didn’t catch on. Some students complained about the sequence of courses, and so changes were made. Lavine acknowledges that the innovations have required some tinkering. “The best time to teach a class is the third time,” he says.

In early June, Northwestern’s general faculty committee passed a resolution charging that the curriculum changes had been implemented without a vote of Medill teachers. The resolution warned of “curricular changes that are ill considered” that could demoralize faculty and cause “damage to the national reputation of the school.” On the defensive once again, Lavine said the Medill faculty had, indeed, been deeply involved. He acknowledged that the changes were being put into place faster than the university usually moved, a pace required because of the “unprecedented extent and rate of change happening in the world in which Medill graduates will work.”

Although the committee vote was simply a resolution and carries no specific power, it suggests a significant measure of discontent with the changes and perhaps Lavine’s bold style, which has been described as autocratic. In any case, Lavine is not about to step back from his grand vision: that Medill needs to produce students who are techno-savvy and consumer-wise. He argues that many working journalists, and even some students, are unwilling to broaden their views about the ways to tell a story. People’s ways become calcified. “I tell some of the students, You’re too old—bring me your nine- or ten-year-old siblings.”

To make his point, he clicks his computer and up jumps an interactive tool created last year by Medill’s newsroom in Washington. “Who Are You?”—an animated Flash application produced by graduate students—leads the “player” on a quest to see how many agencies keep information on him or her, and just what kinds of personal information they have. “Video games have all the elements of storytelling,” says Lavine. “If you think about it, the video game is the typewriter for an eight-year-old.”

It is a notion that makes some Medill students cringe. But Andrew Gruen gets it exactly. He says he grew up on his father’s lap playing video games, then went to Northwestern and “majored in indecision” for more than a year. In the changing cyberworld of journalism, he suddenly saw exciting new possibilities. He jumped eagerly to Medill, and it has paid off in spades. Gruen’s Web skills landed him an internship at the British Broadcasting Corporation in London. When he graduated in June, he had job options to weigh, including one from Microsoft. In the end, he took a position at WESH-TV in Orlando, Florida, to be a digital executive producer on the station’s Web site. “It’s amazing what can be done in journalism with technology,” he says. “And we’re going to be seeing even more amazing things to come.”

Loka Ashwood, who graduated last winter, sees it a different way. She wrote a scathing piece for The Daily Northwestern about the changes at Medill, a place she once saw as “a shining pillar of journalistic integrity.” She became disillusioned with the new direction. “I haven’t forgotten why I came here,” she wrote. “But it seems Medill has.”

As it charges into the future of an uncertain media world, only time will tell whether Medill is making smart innovations or detouring recklessly from the principles of journalism education. But those aghast at Lavine’s embrace of marketing principles might look back at the school’s history. When journalism instruction started at Northwestern, it was part of the School of Commerce. And during the 1930s, one of its instructors was already teaching students about the importance of knowing the views of their audience. He was soon to be famous. His name was George Gallup.

Photograph: Kim Thornton