THE QUANTIFIED TEEN: In April and May of 2009, Chicago conducted two surveys of teens in conjunction with C&R Research, a local market research company. In the first survey, 296 students between the ages of 13 and 18 from Chicago and its suburbs responded. In the second, 303 responded. Chicago also polled 250 parents for a side-by-side comparison of what adults and their kids think about Internet privacy, dating, and sex.

Related:

8 Teen Dreams »

We profile a science whiz, a professional ballet dancer, a born storyteller, a basketball star, and four others

Major League »

Our panel of admissions experts answer questions about getting into college

Hanging Out »

The teenage social circle, dissected

Ever wondered what teenagers do when they are on their own, out of sight? We have—so we asked them. Earlier this year, we devised a large-scale survey and with a local market research company administered it in two stages: In April, we polled 296 Chicago-area teenagers between the ages of 13 and 18, soliciting their opinions on an array of topics, including friends, school, parents, sex, and drugs. We studied the results, came up with additional questions, and surveyed 303 more teens in May.

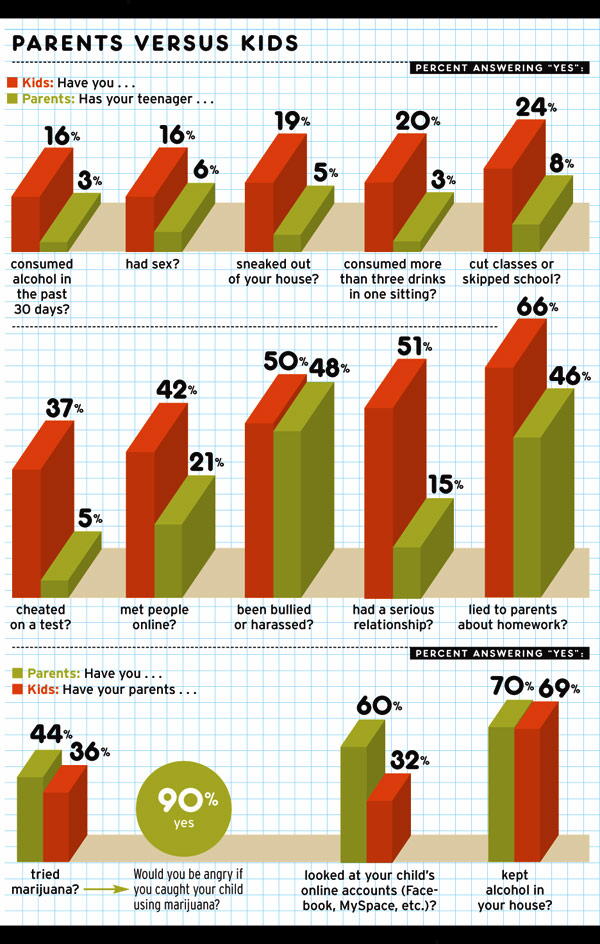

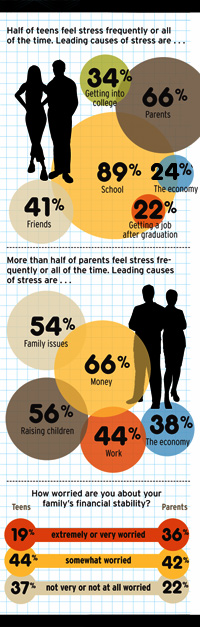

The results (see “The Quantified Teen,” above) often confirmed what we thought we’d find: teens face adultlike pressures—and are giving into them earlier than ever before. Half of the high schoolers surveyed said they had tried alcohol, and 16 percent reported taking a drink in the past 30 days. Nearly a third of the teens said they had ridden in a car at least once with a driver who had been drinking.

Kids also attested to a significant amount of bullying. One in five had seen a weapon at school. Forty-one percent said they’d been bullied or harassed at school, in their neighborhood, or, reflecting our times, online.

The poll also shed light on some of the more banal aspects of teenage life: surfing the Internet, dating, and curfews. Turns out that 29 percent don’t have a curfew; dating starts around age 15; and a third of teens say their parents don’t know what they do online. Teens also copped to some typical bad behavior: 19 percent had sneaked out of their home; 37 percent had cheated on a test; and 21 percent had shoplifted.

Related:

8 Teen Dreams »

We profile a science whiz, a professional ballet dancer, a born storyteller, a basketball star, and four others

Major League »

Our panel of admissions experts answer questions about getting into college

Hanging Out »

The teenage social circle, dissected

The parent-teen relationship is worth examining, too, so we also polled 250 parents and compared their answers with their kids’. The answers were in line when parents were asked whether they had had “the talk” about sex (51 percent of parents said their teen talks to them about sex, while 42 percent of teens said they felt comfortable doing so), but responses diverged widely when it came to topics such as monitoring Internet usage, dating and relationships, and drinking. For example, 20 percent of teens polled had had an episode of binge drinking—consumed three or more drinks in one sitting—but only 3 percent of parents believed their child had ever done that.

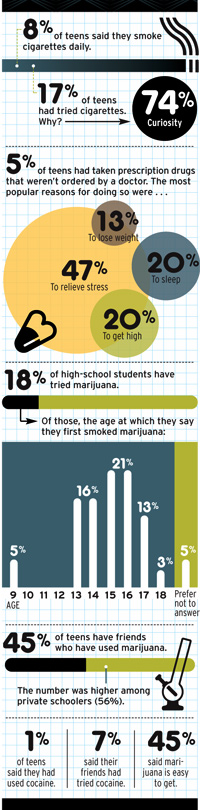

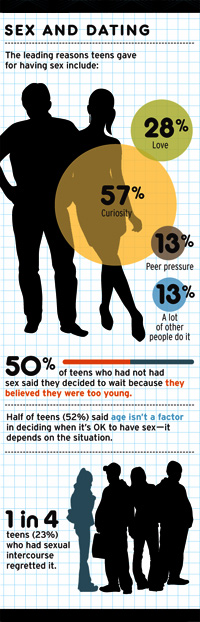

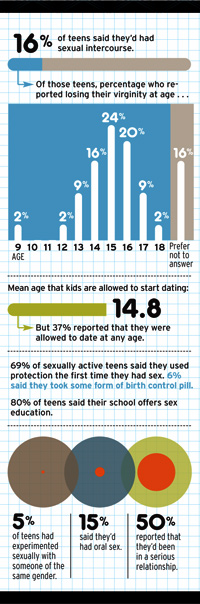

Some results really surprised us, particularly when it came to drugs and sex. Teens reported that the most common places they tried alcohol or drugs were at their own or their friends’ houses. The biggest reason for having sex was to satisfy curiosity (57 percent of teens who’d had sex said that this was the main reason)—beating out love (28 percent) or peer pressure (13 percent). Only two-thirds of the teens surveyed had used protection the first time they had sex.

But no finding perplexed us more than the percentage of teens who reported smoking marijuana (18 percent of high schoolers). The number is actually low compared with national studies: A 2007 Centers for Disease Control (CDC) study of ninth through twelfth graders found the rate to be more than twice as high. Similarly, a 2008 study conducted by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) found that 42.6 percent of high-school seniors said they had tried the drug, as had 14.6 percent of eighth graders. Although reflecting an overall decrease from the late 1990s, both NIH numbers showed slight upticks from the previous year.

|

There are some probable reasons why our poll seemed more conservative than current national findings. Our participant pool skewed young: A fourth of respondents were still in middle school, which is about the time kids start experimenting. That probably accounts for the fact that fewer teens in our survey said they’d had sex—just 16 percent versus 47.8 percent in the national CDC poll. It’s also possible that many in our group of teens, although assured anonymity, answered cautiously—our poll was conducted by a market research firm, which may have led them to worry about how their answers would be used. Further, the teens took the poll at home, monitored by parents; national polls are given at schools, which tend to be more neutral arenas. Whatever the reasons, the discrepancies demonstrate the problems in polling as a method of studying teens.

Of course, today’s teenagers are not a homogenous bunch. We knew that polling could never give us the complete picture, so we conducted 45 extensive interviews with teens from the city and the suburbs. We wanted to know what teens were thinking, how they chose their friends, what they did behind closed doors. We wanted to hear about their lives in their own words. “Growing up in Chicago, I feel like I’ve seen and done more stuff,” said one 17-year-old Urban Prep Charter School student we’ll call Jaylan (to protect their privacy, we have changed the names of the students quoted in this story). “I feel like I’ve done what a senior in college would.”

Although we spoke to plenty of teens who had never tried marijuana or whose cheeks grew red at the very mention of sex, we found that the responses gathered in these less-formal exchanges support some of the more troubling national findings, particularly when it comes to the prevalence of drug use. One question that elicited a robust response was whether life is harder or easier for today’s teens than it was for their parents. Most teens insisted it was harder, and when we asked why, one word inevitably surfaced: pressure.

There’s pressure to have the right clothes—Uggs and designer jeans and $200 sneakers. There’s pressure to drink and smoke and fit in with the crowd. Teens also reported pressure to meet or exceed their parents’ lifestyle. “One of our teachers asked why we try hard in school,” said a New Trier Township High School student, 18. “I raised my hand and said it was because my parents would kill me [if I didn’t]. One girl said it was for maintaining the lifestyle we live right now. A lot of the kids I know are worried about not living up to their parents’ expectations.” She went on to describe how that translated into additional Advanced Placement (AP) courses, extracurriculars, volunteer hours, and, for her, even a part-time job. “There’s a lot of pressure to succeed, so when [kids] have free time, they go crazy.”

Then there’s pressure to do drugs and to have sex or oral sex. These topics—and the related problem of teen pregnancy—were the ones that our teens rated highest among issues facing their generation. Here are those issues in their own words.

|

Drugs

He’s a good kid: just graduated from Oak Park–River Forest High School, headed to college. Likes Dr. Pepper and playing his Les Paul. Plenty of friends. Drinks beer when he can get it. But marijuana is easier to find. It’s around so much, he says, that choosing not to indulge can sometimes be difficult. “There’s a reason they call it Smoke Park–Reefer Forest,” he said matter-of-factly.

A friend, also a graduate of Oak Park–River Forest, recalled, “I was in the middle of a deal during a standardized test last year.” He passed money one way, drugs the other. “It’s huge at our school,” he said, “so huge you don’t think it’s even a problem.” Why did he think marijuana is so prevalent? “We have the financial stability of a suburb and quick access to Chicago. Those two don’t mix.”

Although alcohol is still the entry-level substance of choice for most teens, marijuana appears to be catching up. And the drug is commonplace not only at Oak Park–River Forest, where the high school recently conducted its own survey and found that a third of sophomores and half of seniors had used it in the past year. Teens throughout Chicago and its suburbs described the same widespread use and expressed the same blasé attitude toward it. In fact, several teens told us that marijuana is easier to get than alcohol.

“New Trier loves drugs,” said 18-year-old Heather. “You know how in The Breakfast Club, there is the stoner, the preppy, the jock? Here, everybody smokes pot. The AP kids do it; the not-so-smart kids do it. The jocks do it. The people with money get into prescription pills, cocaine—those things are more accessible because they have money. But everybody smokes pot.”

Everybody—an exaggeration? Kristine Schmitt, who, as student assistant program coordinator at New Trier oversees the school’s vast drug prevention campaign, says that the administration is keenly aware that some students choose to drink alcohol or smoke marijuana. But, she adds, “it is not at the same level as kids perceive it to be.” Schmitt cites a 2006 school survey, which found that perception, at least when it comes to drinking, is different from reality: “In that survey, 42 percent of kids had had one drink of alcohol in the past 30 days, but 90 percent perceived that most students had.” Meanwhile, 31 percent had tried marijuana, but 82 percent perceived that most of their peers had. The point, Schmitt says, is that only kids who try it, talk about it. The rest stay silent—and don’t defend their point of view. “Kids tend to not speak up about non-use because of concerns or pressures to fit in.”

Related:

8 Teen Dreams »

We profile a science whiz, a professional ballet dancer, a born storyteller, a basketball star, and four others

Major League »

Our panel of admissions experts answer questions about getting into college

Hanging Out »

The teenage social circle, dissected

“I don’t see it as a bad thing anymore. A lot of people I look up to smoke weed. Should I think less of them?” That’s Jaylan, the Urban Prep Charter student who lives on the South Side. “My parents divorced, and my pops started smoking weed every day. Every day when I come home.” He paused. “A lot of people do it. It’s not necessarily a bad thing.” It becomes a bad thing, he added, when you get addicted, and addicted means being unable to function. His litmus test: “Can you get your work done and still be serious?” If not, he said, you have a problem.

Jaylan started smoking marijuana in the summer before tenth grade. His friends were doing it, and he said no for a while, but the pressure “wears and tears on you.” He doesn’t smoke anymore, but it doesn’t bother him when his friends do. In fact, the only time he worries about marijuana is when it might be mixed with something. “You see pretty foul stuff—mixing weed with whatever’s in the medicine cabinet, or meth, or cocaine, even cough syrup. It doesn’t matter if you go to a ‘well-off’ school. Those kids have access; they don’t have a care in the world.”

|

Back in Oak Park, two 18-year-old girls talked about the first time they smoked marijuana. “I was with a friend who had done it, and I wanted to try it,” said one. “I was a junior at the time, and it was almost weird that I hadn’t done it yet.” The other girl chimed in: She had tried it at a party at a friend’s house when she was 17. “She’s two years older, and we were with older people. We were all drinking. They passed around a bowl, and I tried it.”

Is marijuana use widespread enough to be a problem? The Oak Park girls were unsure. Processing the question aloud, they started rattling off reasons why not: “It’s safer than drinking when it comes to driving. It’s not addictive”—or is it? One remembered a friend who had struggled with trying to quit. “It’s so casual that people who have problems don’t get them addressed,” the girl said quietly. “He didn’t have enough voices around him telling him to quit.”

Experts say that the problem is frequency—many of the teens we talked to said they knew people who were regular marijuana smokers—and the early age at which kids are getting started. “When we know many times that adults can’t self-control, how can we expect someone with less experience to self-control?” asks Bennett Leventhal, a child psychiatrist and professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC). (See “The Young Brain.”)

We asked a roomful of teens from Whitney M. Young Magnet High School and Lane Tech College Prep, two top Chicago high schools, if pot is prevalent. Yes. Is that a problem? They stared blankly until one 18-year-old boy, to the amusement of his friends, started to recite a litany of reasons why marijuana should be legalized. He had written a paper earlier in the year advocating legalization —a choice his friends found ironic, since he’d never tried the drug.

“My thesis was that if you legalized pot, it could be used for medicinal purposes, and it could be profitable to the government by ridding it of its black-market value,” he said, echoing the political debate over legalization. “We have this moral sense of taking in certain substances into our body, but our decision to do so is supported by the Constitution. Cigarettes are worse for you in so many [more] ways than marijuana is.”

We asked why he hadn’t yet tried it. “I don’t want to,” he said, as his friends nodded in support. “Mostly because I know that it’s a quick fix. Also, I’m strong willed, but for all I know it might snap something in my brain and I’ll say, I want to keep doing this. I know it’s not addictive—but why risk it?”

|

Sex

Britney Spears going without underwear; Paris Hilton making a sex tape. These are the role models our culture puts forth for young women. A 14-year-old Walter Payton College Prep student told us that she felt pressured to kiss other girls at parties because the boys they hung around with had seen similar behavior on the Internet. “They’re growing up in a hooking-up culture,” says Sharlene Azam, a Los Angeles–based journalist who interviewed 100 teen girls across the United States and Canada for her new book, Oral Sex Is the New Goodnight Kiss. “Parents don’t want to believe kids have intercourse, so the talk is usually once, in a clinical and difficult manner. For a lot of kids, where they get their information about being sexual is from the Internet and pop culture.”

It’s not that love has disappeared completely from teen relationships. It hasn’t—but, teens said, love is no longer a prerequisite for fooling around. In fact, teens said you hardly need to know a person to make out or “hook up,” a mighty term with a pretty fluid definition. When asked, teens explained that hooking up generally means doing something more than kissing—with no strings attached.

One New Trier senior, Melinda, explained that getting pregnant wasn’t socially accepted on the North Shore. She and her friends could count on one hand the number of girls they knew who’d gotten pregnant and chosen to have the baby. But that didn’t mean that kids weren’t having sex. “There is a lot, lot, lot of oral sex,” she said. Her curly hair framed her face, which looked younger than that of an 18-year-old. “I think it’s because, first, it relieves you of going all the way. Second, it finishes the job. Third, as a girl, if you are a little self-conscious, you can do things without showing off your body.”

“It’s quicker than sex,” said one 16-year-old boy, talking about oral sex. “You don’t have to take off your clothes or get too involved.” We asked another group of teens, Do the boys reciprocate? “Not as much,” said one girl, who held tightly to her boyfriend, her arms clasped around his waist.

Related:

8 Teen Dreams »

We profile a science whiz, a professional ballet dancer, a born storyteller, a basketball star, and four others

Major League »

Our panel of admissions experts answer questions about getting into college

Hanging Out »

The teenage social circle, dissected

What role does sex education play in all of this? Nearly 80 percent of teens in our survey said their school offered it, but the message there, teens said—and it didn’t matter what area of the city or which suburb they lived in—is, Have safe sex, if you have it at all. In other words, if abstinence isn’t an option, use a condom when you have sex, and that’s that. “There has been so much emphasis on abstinence education, and when parents talk to their kids about sex, it’s very narrowly defined in the minds of both parties as intercourse,” says Azam. The problem is that at least half of the teens we talked to did not think oral sex counted as sex. What’s more, many teens didn’t seem to consider that STDs were a possible outcome.

When we asked if oral sex counts as sex, Melinda wasted no time answering the question. “You could argue it either way, but I’d say the majority of high schoolers don’t take it seriously,” she said. “It’s been around for a while, like [since] eighth grade, when that stuff started happening.”

Pressure to talk about sex—and know what you’re talking about—starts young, teens say, mainly with jokes and innuendo. “[Sex] is the undertone of every conversation,” said one Whitney Young girl, 16. And it progresses. “You need to get laid.” That’s what the friend of one 18-year-old Roosevelt High School senior told her, as if it were a badge that she needed to wear. The casual nature of it all baffled her. “[They] claim to be my best friends,” she said. “They say it’s been six months for them, or three months [since they’d had sex], and they make it seem like that’s weird.”

One 15-year-old Whitney Young student, who plans to wait until she’s older to have sex, said this: “Love is a word that I feel like, with teens, in relationships, has lost its value.”

Teen Pregnancy

|

In Chicago, one of every seven babies is born to a teen mother; in Illinois, in 2007, it was one in ten. These numbers make public health experts cringe: After three decades of decline (both nationally and in Illinois), the number of teen births is again growing—and so are concerns about neglect and abandonment and a continuing cycle of poverty, since many of the babies are born to low-income parents. In Chicago, an overwhelming majority—57 percent, according to the Chicago Department of Public Health—of teen mothers are African American.

Over lunch at a Thai restaurant, two juniors from Wells High School, a public school in East Ukrainian Village, talked about several of their friends who had recently become pregnant. “It’s not just our friends, it’s the whole school,” said one, 17, a shy Latina with a fresh bob. She described an environment where girls were congratulated when their baby bump began to show; how a friend had gotten pregnant just to keep a boyfriend. “Especially in my neighborhood, there is a lot of girls getting pregnant who are barely 14, 15, and it’s, like, OK.”

“Many girls don’t have a sense that they own their own bodies,” says Judith Musick, the Highland Park–based author of the seminal 1993 book Young, Poor, and Pregnant. “Maybe they don’t feel empowered enough to tell their boyfriends no or to say, ‘You have to stop now.’ They are afraid they’ll lose a boyfriend.” Musick points out that girls from financially stable families who get pregnant have more options, including abortion (one in three teen pregnancies ends in abortion, according to the Guttmacher Institute, a think tank based in Washington, D.C.). But they also have a lot of reasons to avoid pregnancy. “They have good schools and all kinds of activities; there are all kinds of things that build their competence and their options as they grow up. You can’t be something else if you don’t see something else,” says Musick.

At Christopher House, an agency that provides doula services, counseling, and mentoring to teen mothers on the North Side, there was a young mother named Mary, 16. Pretty, with long brown hair, and surprisingly sure of herself, she is trying to earn enough credits to graduate from her high school on the Northwest Side and find money for diapers. On this morning, her petite arms encircled her 11-month-old chunk of a son, who bounced and giggled and waved his hands as she spoke.

“My boyfriend and I had unprotected sex, and I went for the morning-after pill the next day,” she said. “They did a test—they told me I was four weeks pregnant.” Despite the hardships, she said she loves being a mom. Her boyfriend is also 16, and they’re living with his parents. “I’ve had to grow up very fast,” she said. “But I’ve got motivation to keep going. I want to give our son a good future.”

Of course, Mary’s parents weren’t happy about it—“my mom was really disappointed”—and the wave of disapproval felt even more crushing when a favorite teacher at school said the same. But her classmates were ready with heartfelt congratulations. “Everybody wants to be your friend when you’re pregnant,” “Everybody wants to be your friend when you’re pregnant,” she said.

Beside Mary sat a sweet-faced 14-year-old from Senn High School on Chicago’s Far North Side. She is the new mother of a three-week-old. “At first, I wanted a baby. Life was boring,” she said. But then reality set in, and she realized that motherhood was no way to repair the broken relationship with her mother, so she stopped wishing for a child. After she changed her mind, she got pregnant anyway. We asked why she didn’t use birth control, and she shrugged. Now she’s living with her father, trying to go to school and learn how to be a parent—diapers, midnight feedings, and all.

* * *

Related:

8 Teen Dreams »

We profile a science whiz, a professional ballet dancer, a born storyteller, a basketball star, and four others

Major League »

Our panel of admissions experts answer questions about getting into college

Hanging Out »

The teenage social circle, dissected

Technology

Despite this testimony, today’s generation of teens is no more troubled than the previous generation. Psychologists say so—and the numbers back them up. For example, national rates of teen drug use and teen births are down from the highs of previous decades. (But in a new wrinkle, violence against teens in Chicago is up from previous years, and murders of 14-to-16-year-olds went up 72 percent—from 18 to 31—from 2007 to 2008.)

Still, parents are in a bind: Hover and you risk a rocky relationship with your adolescent; allow too much independence and you quickly lose control. Experts say that today’s parents often veer toward relinquishing control. “Parents are giving [teens] too much space,” says Azam, the journalist and author. Azam says many of the girls she interviewed had nothing to do after school and no supervision during that time. “They were available and open for anyone and anything that came along.”

“We know the peak time of day for kids to experiment with sex and drugs is the hours between the end of school and when parents come home from work. That is a robust and replicated finding,” says Laurence Steinberg, a Temple University psychologist. “And the place where kids are most likely to have their first experiments with sex and alcohol and drugs is within their own home.”

Experts say one way parents can intervene is to start discussing these issues early. “You don’t start dealing with these issues at age 13. If you start at adolescence, you’ve waited a long time,” says Leventhal, the UIC psychiatrist. “You have to start having these conversations at 5, 6, and 7.”

|

And don’t limit the conversation to one big talk about sex and drugs; routine, perhaps even daily, interventions are more effective. “If you are at the supermarket with your daughter and Giselle is naked down to her pubic area on the cover of a magazine, you can talk to your child about why [the model] looks sexually willing and available,” says Azam. “If you don’t, your daughter might look at the image and admire it. This is ‘normal’ behavior, and the next time her boyfriend says, ‘Send me a nude photo,’ she might. Parents have to make kids critics of image-based culture.”

Parents should also get to know their children’s friends. A common thread in our discussions with teens was that they are making decisions in the presence of—and checking their decisions against—a very influential demographic: their friends. Don’t just get to know the other teens, but meet their parents, too. “Parents should also invite parents over, to see if they share the same values,” Azam says.

Finally, parents shouldn’t avoid conversations about substance use or sex out of fear of being hypocritical, says Robin Mermelstein, the director of the Institute for Health Research and Policy at UIC. “You should be able to have an open discussion about what your adolescent is doing,” she says, even if a parent smokes cigarettes, drinks alcohol, or has used marijuana. Instead of saying, “I know you’re going to experiment” and avoiding the topic, she counsels, “Ask open-ended and nonjudgmental questions such as, ‘What are the pressures you’re facing? What are you feeling like?’”

Their answers will likely surprise you.

Additional reporting by Bridget Maiellaro