Inmates at Cook County Jail are allowed three privileges: television, books, and food. The staff has no compunction about denying its most difficult residents either of the first two, but under the Constitution, correctional facilities can’t withhold food. Nothing in the Eighth Amendment, however, says the food has to taste good. “This is not the Four Seasons,” says Tom Dart, the Cook County sheriff. “Inmates who are injuring people in jail will get their nutritional needs met, but we will not cater to their culinary desires.”

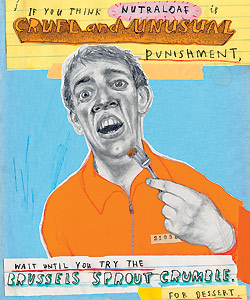

Nutraloaf, a thick orange lump of spite with the density and taste of a dumbbell, could only be the object of Beelzebub’s culinary desires. Packed with protein, fat, carbohydrates, and 1,110 calories, Nutraloaf contains everything from carrots and cabbage to kidney beans and potatoes, plus shadowy ingredients such as “dairy blend” and “mechanically separated poultry.” You purée everything into a paste, shape it into a loaf, and bake it for 50 to 70 minutes at 375 degrees. Eat two a day and, boom, all your daily nutrients, right there. If you want the recipe, ask me.

Or just get yourself tossed into Cook County Jail, where an inmate who causes serious food-related problems buys himself a one-way ticket to Nutraloafopolis. Get caught making homemade hooch in your cell toilet? You get Nutraloaf. Hurl food at a guard or stab someone with a spork? Nutraloaf. Of the jail’s 9,000 inmates, 21 have endured the Nutraloaf program since it began in June. One begged—No! Anything but Nutraloaf!—and another went on a hunger strike. Both men, and virtually every other Nutraloafer, straightened up enough to get back to the usual diet of oatmeal and processed bologna.

In July, I took the afternoon off from my job as Chicago magazine’s dining critic and drove to 26th and California to dine on Nutraloaf. Cook County’s stridently gray-brown cafeteria would never be mistaken for Naha, and the dish’s presentation aims less for the wow factor than the break-your-spirit factor. An employee from Aramark Correctional Services—a branch of the Philadelphia-based company that also provides fare for college dorms and NFL stadiums—presented me a Styrofoam container sagging with a blunt ginger-toned mass roughly the size of a calzone and with the appearance of a neglected fruitcake. It had nothing else in common with either.

The mushy, disturbingly uniform innards recalled the thick, pulpy aftermath of something you dissected in biology class: so intrinsically disagreeable that my throat nearly closed up reflexively. But the funny thing about Nutraloaf is the taste. It’s not awful, nor is it especially good. I kept trying to detect any individual element—carrot? egg?—and failing. Nutraloaf tastes blank, as though someone physically removed all hints of flavor. “That’s the goal,” says Mike Anderson, Aramark’s district manager. “Not to make it taste bad but to make it taste neutral.” By those standards, Nutraloaf is a culinary triumph; any recipe that renders all 13 of its ingredients completely mute is some kind of miracle.

I ate two-thirds and gave up, longing for any hint of flavor, even a bad one. That night, my stomach’s rebellion against the loaf was anything but neutral. I felt so full and lethargic that I skipped dinner and the following breakfast. And let’s just say I finally had a lot of time alone to catch up on my New Yorker reading.

Even though inmates in several states, including Illinois, have sued over Nutraloaf, alleging cruel and unusual punishment, correctional departments everywhere are introducing their own versions of the “disciplinary loaf.” None of the lawsuits have been successful. “We’re not trying to dump Tabasco sauce on their tongues or anything like that,” Dart says. “It just tastes like nothing.” In other words, they found a loophole: Nutraloaf is not cruel; it’s just unusual. Soon it may cease to be either.

Comments are closed.