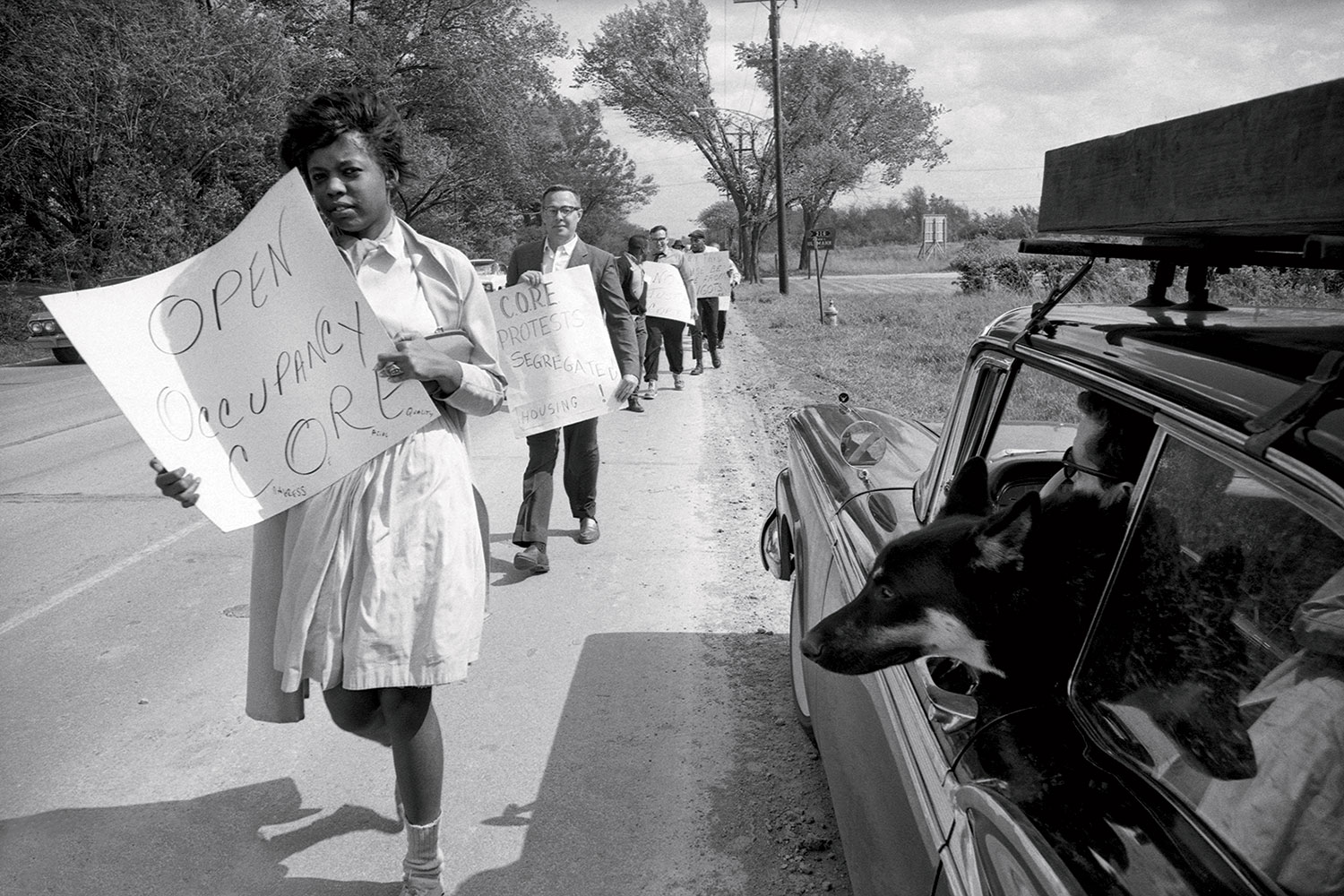

Deerfield Integrationists, 1963 (above)

When Shay, who died in 2018, moved his young family to Deerfield in 1958, he could not have known that the suburb would become embroiled in a national controversy. Developers attempting to build an interracial housing project there were thwarted by residents who got the land reassigned for a public park instead, setting off a protracted legal battle. On May 18, 1963, liberal-minded young people in Deerfield linked up with Chicago civil rights activists for a protest. Between 50 and 100 people marched from Village Hall to the new park, where members of the Congress of Racial Equality had pitched tents. The following month, the U.S. Supreme Court refused for the last time to hear the case, effectively ending the developers’ efforts. It took four more years before the first African American family, Sherman and Eve Beverly, moved into Deerfield, without opposition.

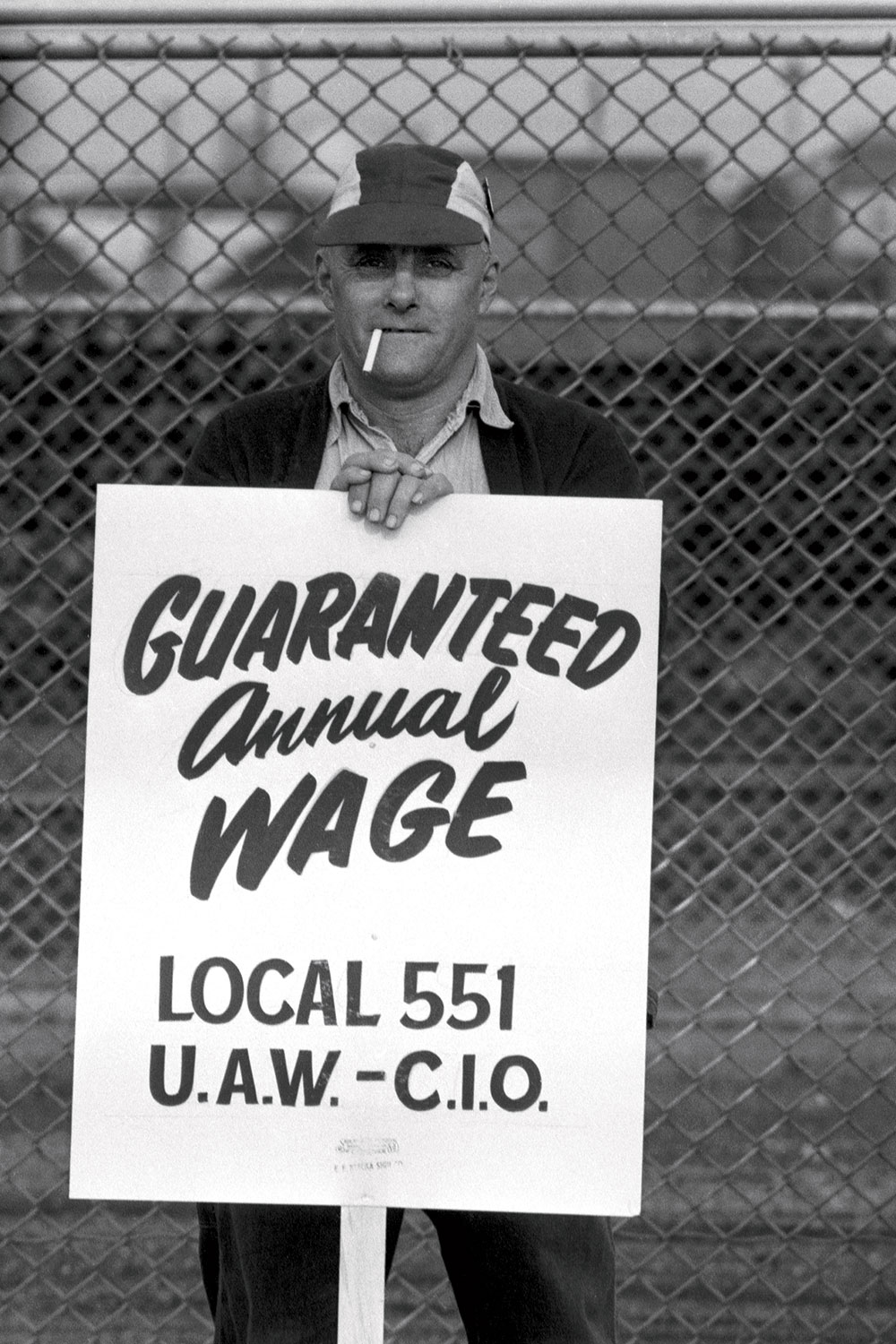

Striking Autoworkers, 1955

In the mid-’50s, labor unions denounced a new pro-business climate that seemed to invite companies to uproot their factories and automate their production, shedding workers along the way. Shay captured this dynamic during a short June 1955 strike of Ford employees at a Far South Side assembly plant. The United Automobile Workers strikers demanded a “guaranteed annual wage” and a reset of labor-management relations to the “proper scale of moral values which puts people above property, men above machines,” said national union head Walter Reuther. Ford and other automakers, battered by strikes such as this one while pressed by high demand, eventually agreed to a modified annual wage, but unions conceded shared control over postwar capitalism.

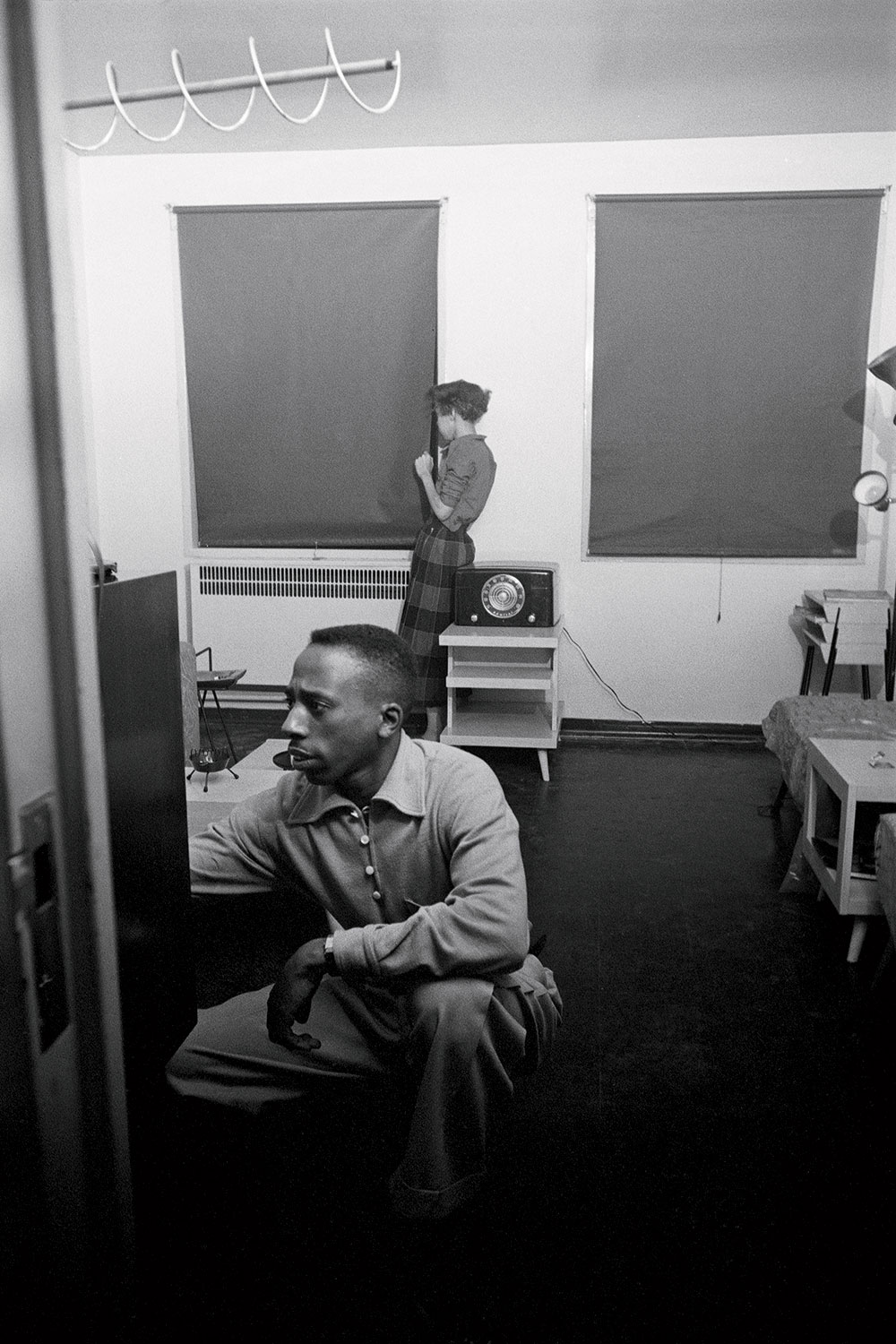

Segregation Breakers, 1953

African Americans’ search for adequate housing in Chicago led many to segregated white neighborhoods — not necessarily as civil rights activists, but as people desperate for a decent place to live. In July 1953, Betty Howard, a light-skinned black woman, was accidentally admitted into the all-white Trumbull Park housing project in South Deering. By that fall, three more black families had moved in, and Life magazine commissioned Shay to document the racial drama. “From the window of their apartment Mr. and Mrs. Edward Johnson look down at [a] night shift of a continuous police watch over them,” read the caption for the photo of officers around a bonfire. The caption for the shot above said the couple “fearfully keep their living room blinds drawn.”

University of Chicago Draft Protesters, 1966

Objecting to the government’s use of special test scores and class rank in deciding who got deferred from the draft, some 450 students took over the U. of C.’s administration building for five days in May 1966. They demanded that the school stop testing and reporting the data to the Selective Service, arguing that it buttressed a caste system. Shay’s emblematic photo features U. of C. grad student Jackie Goldberg, who had been a leader of the Free Speech Movement protest while at Berkeley, guiding activists in a discussion. A sign behind her states, “Don’t Use My Grades to Murder Students.” The demonstration and others on campuses around the country helped end the use of this information as major criteria for the Selective Service, even if the burden of the draft still fell disproportionately on working-class and minority youths.

Democratic National Convention Demonstrators, 1968

Shay was assigned by Time magazine to capture all aspects of the Democratic convention, and his staid black-and-white images of the venue contrasted with his colorful shots of antiwar protesters. He roamed the city with four cameras and a gas mask, photographing subjects who did not always anticipate his presence. Shay’s images thus help separate the history from the mythology. In this photograph, National Guardsmen hold back demonstrators at Balbo Drive and Michigan Avenue, outside the Conrad Hilton Hotel (now Hilton Chicago). This was the spot where TV cameras would capture police inflicting violence upon the crowd as they cleared the intersection — 17 minutes of chaos.

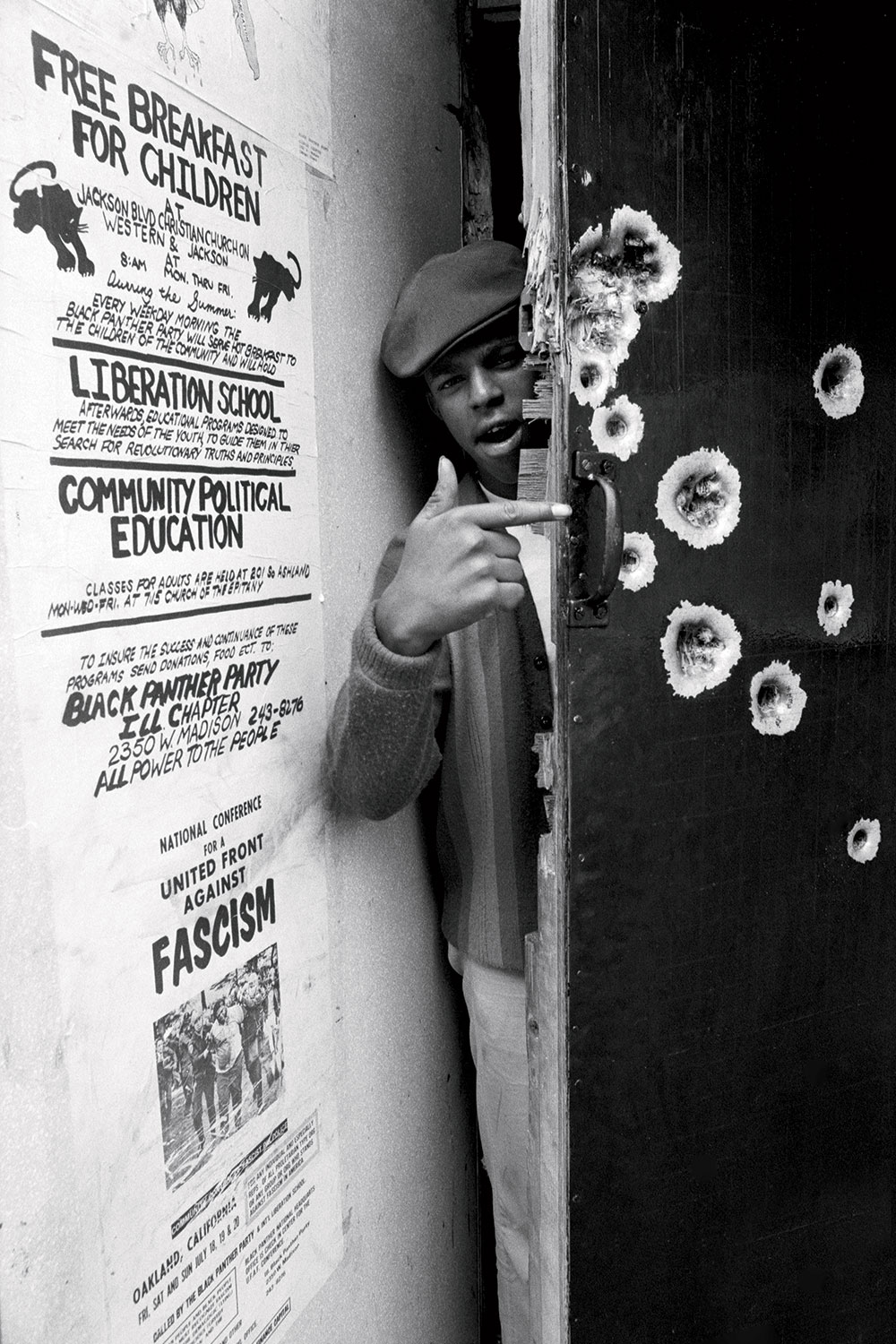

Black Panthers, 1969

The Illinois chapter of the Black Panther Party rose to prominence at the height of black community organizing in Chicago in the late ’60s. The Panthers opened a Near West Side headquarters and under Fred Hampton cultivated their own form of Black Power, which emphasized day-to-day community engagement. The Panthers started a breakfast program for children and a health clinic, while condemning the “avaricious businessman” and the “demagogic politician” who exploited their community. On the last day of July 1969, police broke into the Panthers’ office. Several officers were injured in the shootout that followed. Police arrested three people, ransacked the headquarters, and set fire to the second floor. Shay photographed the aftermath, including bullet holes in the front door. Four months later, Hampton and another Panther were killed in a coordinated police and FBI raid.

Reprinted with permission from Troublemakers: Chicago Freedom Struggles Through the Lens of Art Shay by Erik S. Gellman, published by The University of Chicago Press. © 2020 The University of Chicago. Photos © The Arthur Shay Estate.

Reprinted with permission from Troublemakers: Chicago Freedom Struggles Through the Lens of Art Shay by Erik S. Gellman, published by The University of Chicago Press. © 2020 The University of Chicago. Photos © The Arthur Shay Estate.