When it comes to sexism in powerful and competitive industries like tech and finance, research tends to start with representation: how many women are employed at different levels of the companies? How many are on corporate boards?

If the number's not representative of the general population, though, the problem can be difficult to diagnose. Is the problem in the industry itself? Does it go back farther into the talent pipeline, to graduate school, undergraduate, or even K-12, where young women or girls are gradually dissuaded from picking up the skills they need?

A new working paper, "When Harry Fired Sally: The Double Standard in Punishing Misconduct," from three professors of finance including Gregor Matvos of the University of Chicago Booth School of Business, takes a clever approach to measuring the presence of gender discrimination in finance: what happens to financial advisers after they commit misconduct? The pipeline question is eliminated; the group under examination is already in the industry.

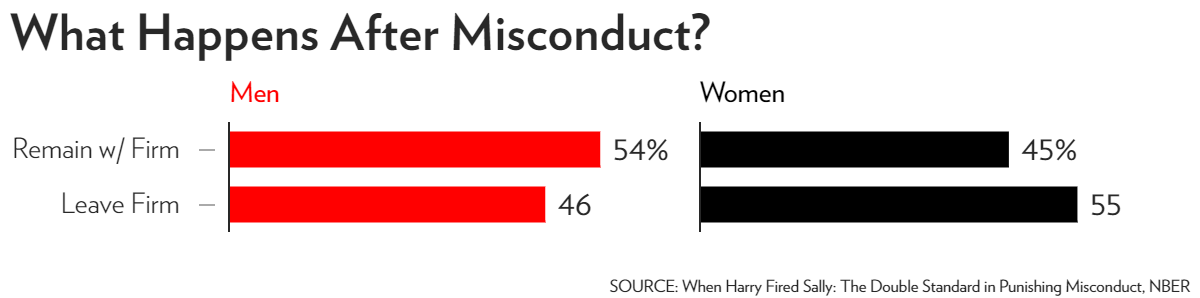

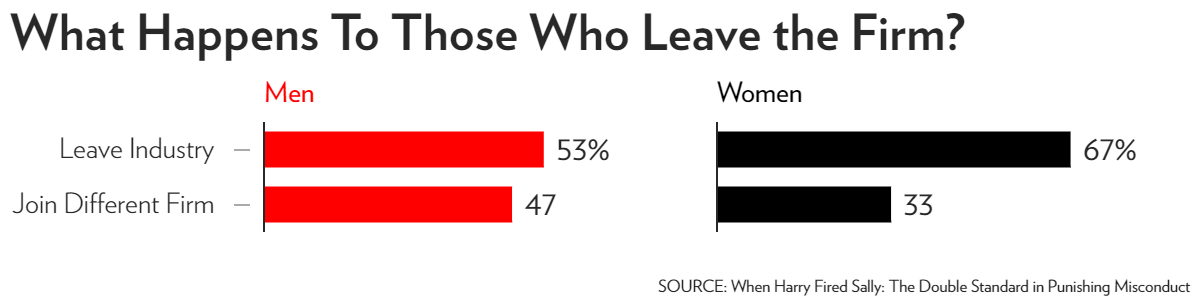

But the results are familiar. Women are less likely to commit misconduct; when they do, it tends to be less serious; but they get punished harder for it. Women are more likely to leave their firms after they are found to commit misconduct, and if they do, they're more likely than men to leave the industry—for a minimum of one year—rather than find a job at a new firm.

One reason they might leave the industry: women who committed misconduct are "67 percent less likely to be promoted relative to other female advisers." For men? It's just 19 percent.

The authors tested whether the the female offenders caused more damage than their male counterparts; in fact, misconduct committed by male financial advisers cost firms, on average, 20 percent more. They tested whether female financial advisors might not be as good at their jobs, and thus firms might be less likely to retain them in the face of misconduct. But the difference between men and women was small in terms of assets managed and productivity; and, when the firms downsized, similar numbers of men and women were laid off.

What did make a difference? More women in management. The authors concluded that "gender differences in labor market outcomes following misconduct are driven by discrimination by male executives of financial advisory firms. Men seem to be more forgiving of misconduct by men relative to women." But there aren't a lot of female executives. In the study, 25 percent of advisers were women, compared to just 16 percent of owners and 17 percent of managers.

Why would men be more likely to receive second chances, even though they're statistically more risky as a gender and not significantly more productive? The authors don't speculate on mechanisms, but finance professor Lily Fang spent five years looking into gender issues in the stock-research field, and found that, perhaps unsurprisingly, "the networking and personal connections that male analysts rely on so heavily to get ahead are much less useful for women in similar jobs." It's who you know: and, possibly, it's not just about getting ahead, but also not falling off the map.