Thanks to the work of Daniel Kay Hertz and Chris Hagan, I've been following the issue of Chicago's vanishing two- and three-flats and its implications for density and affordability in the city. Here's Hertz in 2015:

But because Chicago’s zoning code fits so snugly over its neighborhoods outside of downtown—so snugly, in fact, that maximum allowed densities are frequently much lower than what already exists—builders have not been able to add much new housing. Instead, they maximize their profits by turning two-flats into luxury two-flats, or into mini-mansions for a single family. As a result, as places like Lincoln Park get more desirable than they’ve ever been, fewer people are able to live there, and its population remains about 40% below its peak….

North Center’s shift from multi-unit buildings to single-family homes is one that housing experts, officials and even some residents fear is unsustainable for the housing and retail markets.

I thought of this when I came across a paper from Enterprise Community Partners that presents some compelling evidence that small apartment buildings are critical to housing affordability, thanks to a piece by Patrick Clark at Bloomberg.

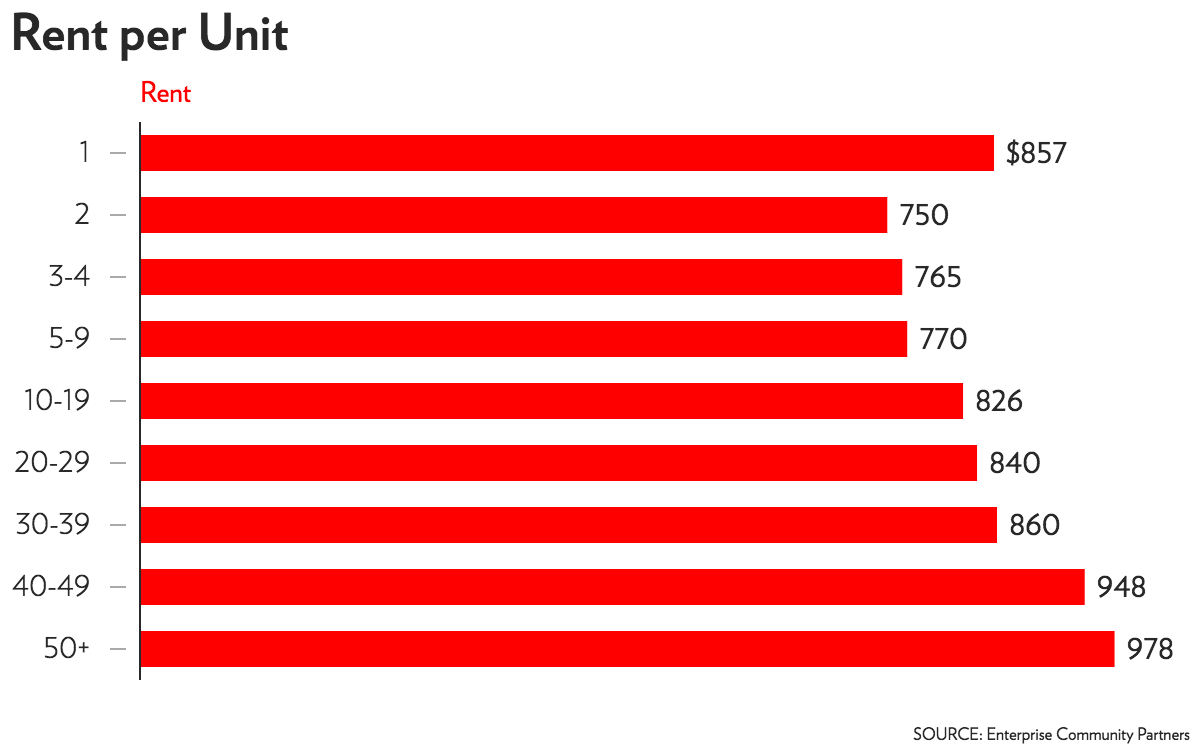

The numbers are pretty straightforward. Two-to-ten unit buildings tend to have considerably cheaper apartments.

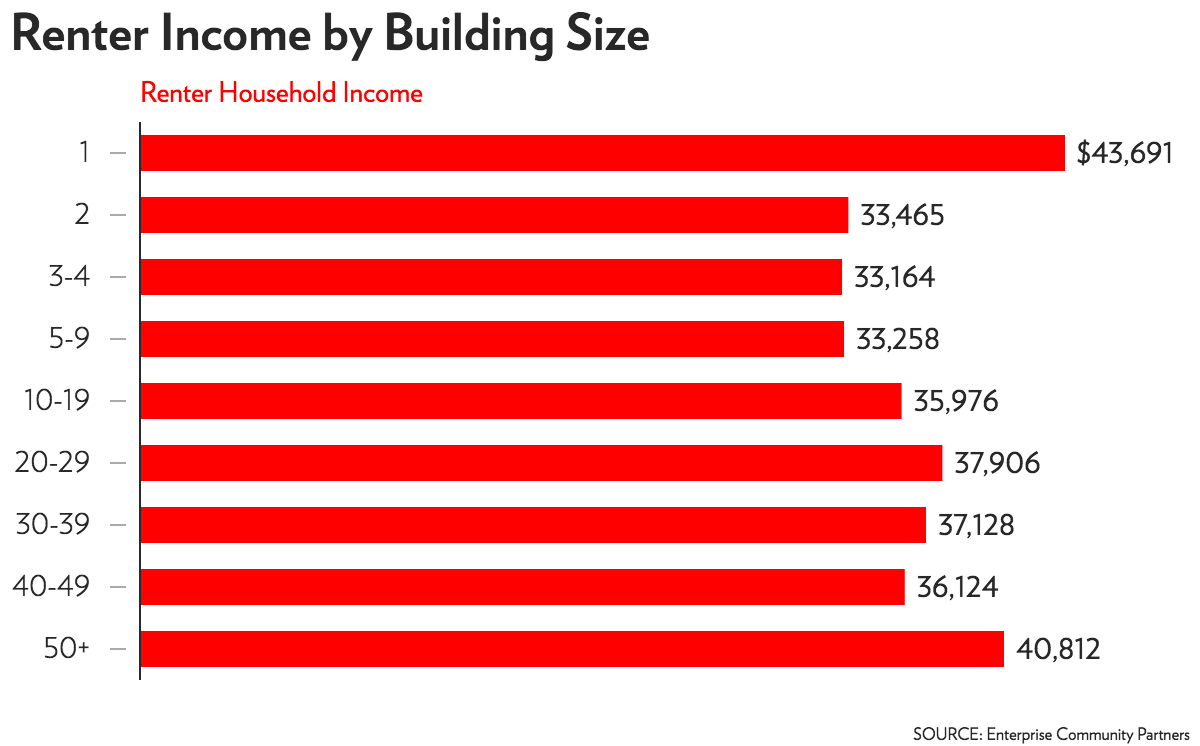

And the people who rent them have lower incomes.

For nationwide averages, those are pretty significant differences, and the pattern is dramatic. In Chicago, smaller apartment buildings were built as affordable housing and carry much of that burden today, but as Chris Bentley reported in 2014, they were hit hard by the housing crisis and aren't getting replaced:

During the housing crisis two-to-four unit properties were disproportionately impacted by foreclosure. And Geoff Smith from the DePaul Institute of Housing Studies says two-flats don’t really make economic sense for new development, so they may well be lost to history in lower-income neighborhoods.

[snip]

He adds that, if older two-flats fall into disrepair, there will likely be no two-unit rentals to replace them. “The concern is that in some of these more distressed areas, where there is a substantial stock of these buildings, […] this kind of housing could be lost,” he says.

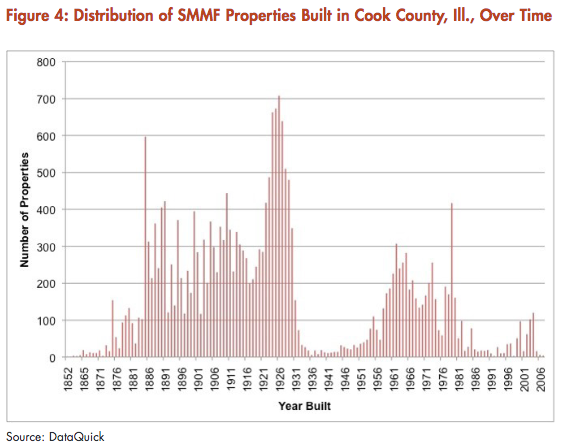

Smith has a point. The paper looks at when small and medium multifamily housing (SMMF) of 2-49 units were built in Chicago, where 2-4 unit buildings are especially common.

Some of this building activity correlates with immigration/migration and economic conditions, of course, but there is much less construction of these units than in previous decades.

Either way, they don't seem to be getting replaced. The authors don't really get into why, though in Bloomberg Smith mentions exactly the zoning issue that Hertz and Hagan have covered: "Zoning rules have developed to favor single-family construction, making it harder to win approval for larger projects. There are regulatory costs to building multifamily housing, and developers that go through all the trouble to win approvals want to build more than just a few apartments."

That's something Chicago will have to consider as its old warhorses of affordable housing age out of existence.