Yesterday City Council held a five-hour meeting on a story that's been going on for a couple years now—the closure of city mental health clinics. The city says that "care for the mentally ill actually has been expanded"; an official from the county jail, which has put itself at the forefront of civic mental health treatment, says they're dealing with more inmates suffering from mental illness than ever:

The city now says that there were 2,798 patients in the clinics at the time half were closed. Choucair told the Tribune that many of the patients on the original list were no longer “active,” and that all of active patients either remained with the six surviving clinics or were referred to another provider.

Dr. Nneka Jones, who heads up mental health services at the Cook County Jail, has described the jail as the largest mental health facility in the state if not the country. She said the numbers of mentally ill detainees has grown about threefold to 2,800 in the past four years.

Tom Dart has been pushing this issue for awhile, in part to take pressure off the perpetually overcrowded jail he oversees, arguing that dealing with petty and/or victimless crimes like shoplifting and prostitution through a mental-health framework is ultimately cheaper in the medium and long term.

San Antonio was dealing with a similar problem as the 21st century began. True to Texas's law-and-order stereotype, the jail was filling up as a result of zero-tolerance policies. Against that stereotype, the city decided to divert certain criminals, dealing with mental illness and alcoholism, into specialized mental-health facilities while training police in mental-health intervention. Kaiser Health News has a fascinating report on it:

Everyone contributed funding to create the Restoration Center. It offers a 48-hour inpatient psychiatric unit; outpatient services for psychiatric and primary care; centers for drug or alcohol detox; a 90-day recovery program for substance abuse; plus housing for people with mental illnesses, and even job training.

More than 18,000 people pass through the Restoration Center each year, and officials say the coordinated approach has saved the city more than $10 million annually.

It's not the first report on the Restoration Center. Journalist Pete Earley, whose interest in mental health and the criminal justice system (and his book Crazy) was inspired by his own son's experience with those institutions, admires their work:

I’ve visited the CCC [a 24/7 Crisis Care Center, part of the chain of services], as it is called, and have seen how easy the center has made it for law enforcement to drop off individuals with mental illnesses for care rather than booking them into jails or emergency departments.

But Bexar County didn’t stop there, it began providing housing with close accessibility to the support services that individuals need to recover. This includes a restoration center that provides medical detox and a broad array of substance abuse services as well as sobering services and medical clearance screening. Most importantly, Bexar County integrated psychiatric care, transitional housing systems and general health services or to be blunt — it began providing wrap around services to people who needed help.

The Restoration Center's offerings are fairly fine-grained. There's a very short term "sobering unit," in which treatment lasts four to six hours; a three-to-five-day detox, a 16-week intensive outpatient service; methadone treatment; methadone and outpatient treatment specifically for pregnant women; a community court; housing for the homeless; and more.

It's been open five years, opening eight years after Bexar County started building its diversion treatment. First they started training the cops; then they opened a "speciality jail diversion facility;" then the Crisis Care Center. In other words, it's been assembled piece by piece, and it continues to expand. Recently the Restoration Center started diverting veterans from the sobering unit into a vet-specific program, and the initial returns from the pilot study have been positive:

Outcomes determined from repeated measures analysis of baseline, 6-month, and 12-month interviews include clinically and statistically significant change in trauma symptoms (mean PCL-C scores reduced from 67.70 to 49.60, p<=.001), significant reduction (p<=.05) in homelessness (70.5% to 13.7%) and a significant increase (p<=.001) in veterans working full or part-time (14.7% to 26.8%). There were also significant improvements (p<=.05) on all of the BASIS-24 subscales (Depression/Functioning, Relationship, Self-Harm, Psychosis, and Substance Abuse).

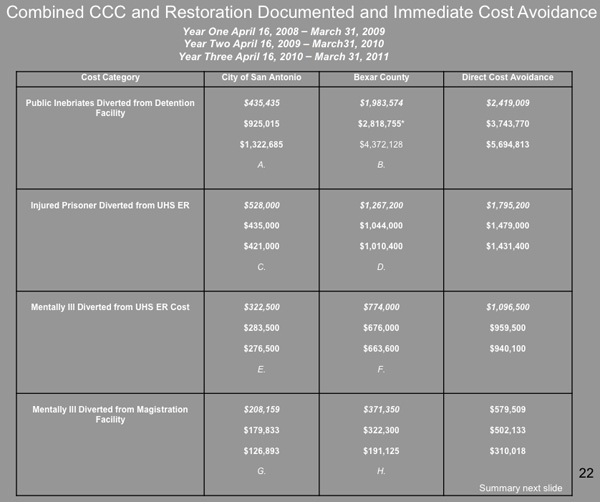

As the Kaiser piece noted, Bexar County is reporting significant savings from its jail diversion. Here's an example of how that breaks down:

Perhaps surprisingly, the biggest line-item savings came from not locking up "public inebriates."

It's drawing interest. Fresno is attempting to copy it; so is Portland. Houston copied the sobering unit. The upfront costs are nontrivial, as Fresno is learning, and San Antonio's model may look daunting in the number and sophistication of its pieces, but it's been almost 15 years in the making, piece by piece.