Donald Trump’s march to the White House followed a road paved by potent emotions. From its conception, his campaign tapped heavily into fear. After all, the 45th commander-in-chief announced his presence in electoral politics by smearing Mexican immigrants as criminals and rapists. He went on to stoke fear of “radical Islamic terrorism,” crime in Chicago, and an allegedly soaring murder rate nationwide.

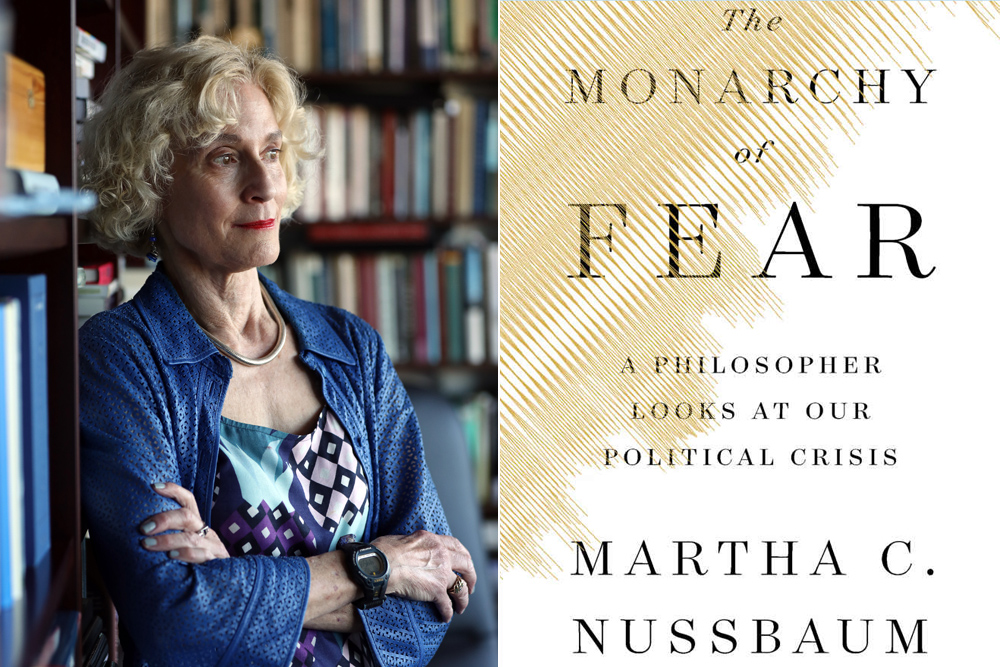

His surprising victory likewise sent shudders of fear through many. University of Chicago professor Martha C. Nussbaum, a philosopher appointed in the school’s law school and philosophy department, was among the ranks of the fearful on that night. “As I examined my own fear, it gradually dawned on me that fear was the issue, a nebulous and multiform fear suffusing US society,” she said in her new book, The Monarchy of Fear: A Philosopher Looks at Our Political Crisis (Simon & Schuster). That realization became the inspiration for the latest treatise by the prolific author. Her book weaves together elements of history, philosophy, and human psychology in evaluating of the role fear in contemporary politics—and its dangers.

Chicago magazine caught up with the philosopher by phone to discuss her work and her thoughts on how to keep fear from wreaking havoc upon our politics. The highlights from the conversation, below:

What do you hope people get out of the book?

I hope that they get out of it a kind of habit of looking within and thinking about how the personal and the political are so closely interwoven—always. In general, I agree with Socrates that what democracies badly need is the examined life, and we need to think critically about ourselves. But Socrates didn’t think critically about the emotions. And I think we have to do that too, and very powerfully so at this particular time.

So thinking about: Why are we doing what we’re doing? What are the motives that prompt us? And are these really things we want to stand for in our lives? What are the alternatives—what are other ways of conducting politics? I talk a lot about Martin Luther King Jr. in the book, because I think he understood this point—that you have to get a productive political movement. You have to address anger, fear, and then to think about what the alternatives are: hope, faith, a certain kind of brotherly love. And then you have to set yourself to cultivate those. And otherwise you’re just going to be talking on the surface.

Talking about hope as an antidote to fear, Barack Obama once fashioned himself as sort of an avatar of hope. In the political sphere, do you see promising advocates for hope today?

I see quite a lot. I see all these young politicians who are for the first time running for office, including a very large number of women. The newspaper today had a story today about how women are basically quickly taking over in state legislatures. These are the invisible jobs, but they’re very, very important. So all these first-time people in politics. I also think protest movements, of the sort we’re having in Chicago—a march about immigration and families—are of pretty limited usefulness, but they still are useful, and they get people involved in the search for justice.

I think a lot of people get hope through civic organizations and through their churches. … A lot of hope is local. And I think that’s very important: that people don’t need to think ‘oh, how can I change Washington?’ They shouldn’t be thinking that way for the most part. But they find hope in their own communities.

What do you think are the best ways to neutralize the politics of fear?

You just have to stand up and criticize it. It’s exhausting. I’m sure that a lot of the media are feeling exhaustion because they say the same thing again and again. But I’m afraid you do have to say the same thing again and again. You have to try to get through to people through whatever media they see. It’s more difficult to do today than it was maybe 30 years ago, because people’s media connections are so plural. So instead of just having three networks that everyone was listening to, they’re getting the news from the Internet and often avoiding things that they disagree with. So that’s more difficult. And I sometimes find that members of my family are reading completely different news from what I’m reading, because they’re not reading general interest newspapers at all. They’re getting all their news from certain Internet sites that are rather political. So yeah, it is an exhausting thing to try to keep criticizing—keep the truth out there—but I think that’s the first thing that you really have to do.

And then, I think just bringing people together in constructive ways to address the real problems that exist…. All over the country, often locally and sometimes in state government, there are things that people can do to give other people and themselves a feeling of forward movement.

If we’re at a particularly angry moment right now in America do you think there have been any times in our history when anger subsided more?

I do want to pause for a moment at what you say to say I distinguish two separate parts of anger—the protest part that says ‘this is outrageous and it better not happen again,’ and the part that says ‘oh, right, the way to right this is to inflict painful payback on the person who did it.’ Now, I think our moment is not so clearly an angry moment in the latter sense. I think we are seeing a lot of protest about the separation of children from their parents and the policies at the border. But by and large, it is forward-looking, and it’s not retributive. I think it’s actually quite exemplary in that way. People are not saying, ‘oh the way to solve this problem is just to inflict great pain on all Republicans.’ No, they’re saying, ‘we want to restore these children to their parents.’ So I’m not sure this is a particularly angry moment.

Martha Nussbaum on "The Election of 2016, Powerlessness, and the Politics of Blame" at the University of Denver last year: