Over the weekend, the world saw more unrest coming out of Chicago than at any time since the 1968 Democratic National Convention. As protests over the killing of George Floyd gave way to property damage and skirmishes between police and demonstrators, squad cars were smashed, grocery stores were ransacked, and retail, including the 121-year-old Central Camera on Wabash, was set ablaze. For the first time since the 1970 Kent State shootings, a Chicago mayor asked an Illinois governor to send in the National Guard.

Lori Lightfoot’s condemnation of the protestors was nearly as strong as Richard J. Daley’s in '68. Back then, Daley called anti-war protestors at the DNC “a lawless, violent group of terrorists.” Lightfoot used the words “disgust,” “obscene,” and “criminal” to describe those who introduced mayhem to the George Floyd protests.

“You don’t come to a peaceful protest with a bowling ball or a hammer or a shovel or a baseball bat,” Lightfoot said at a Saturday night press conference, just before announcing a 9 p.m. to 6 a.m. curfew. “You don’t come to a peaceful protest with bottles of urine to throw at police officers.”

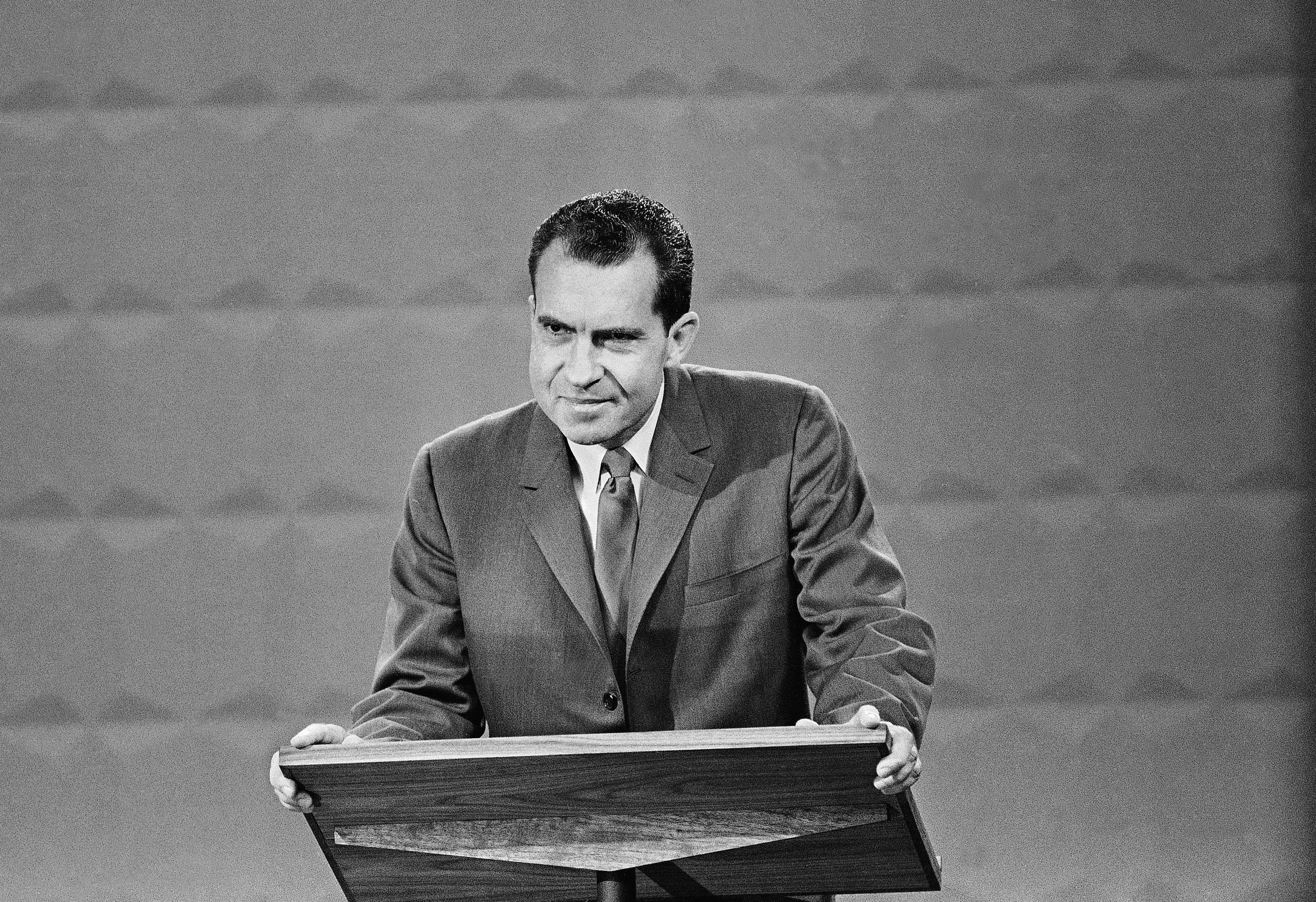

Chicago was the site of two major civil disturbances in 1968: the DNC protests and the West Side riots that followed the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. In both cases, Richard M. Nixon was the political beneficiary. The most cunning politician of his generation, Nixon clawed his way out of the civic graveyard by promising to end the urban riots and campus anti-war protests of the 1960s, restoring “law and order” to the nation.

Nixon believed that people vote more out of fear than hope. In his book Chicago ’68, historian David Farber wrote that most Americans who watched the DNC on television sided with the Chicago police, who beat protesters with billy clubs: “Many, in revulsion to what they saw as the riotous conditions created by a liberal administration, turned to the law-and-order candidacy of George Wallace. Others responded to the bloody convention by joining ranks with conservative supporters of Richard Nixon.”

Likewise, counties that were near the '68 riots swung toward the Republican Party by 6 to 8 points nationally that November. In Illinois, every suburban county went to the GOP. The state, which had voted for John F. Kennedy in 1960 and Lyndon Johnson in 1964, elected Nixon, then voted Republican in the five presidential elections that followed.

Nixon’s election broke apart the New Deal coalition, which had ruled American politics since the Great Depression. His presidency began an era of reactionary conservatism, of which Donald Trump is the current avatar. Trump, an admirer of Richard Nixon, is already using his hero’s slogan to try and salvage a re-election campaign that's flailing as a result of COVID-19 and the 20 percent unemployment it's produced.

“We must have law and order on our streets and in our communities,” Trump’s attorney general, William Barr, said on Saturday. On Sunday, Trump simply tweeted “LAW AND ORDER” in all caps.

It’s an issue perfectly suited to reconnect Trump with his base. Trump won the Republican nomination, and then the presidential election, by appealing to white fears and anxieties. In his 2016 Republican National Convention speech, Trump described an America threatened by terrorism, illegal immigration, and the killings of police officers, then declared “I alone can fix it.” The nation Trump purported to protect consisted exclusively of white Americans, and he presented himself as an indispensable strongman, the only man capable of restoring order. It worked, though.

Could Trump use last weekend’s protests to make it work again? It may be his best chance to hang on to the votes of the economically liberal but socially conservative white working-class voters who helped him win most Midwestern states in 2016.

“Trump won by flipping suburban white voters in 200 counties that Obama carried in both 2008 and 2012,” Alvin Tillery, director of Northwestern University's Center for the Study of Diversity and Democracy, recently told NBC News. “Although these voters display less racial resentment that Trump’s hardcore Southern base, it is still a part of their ideological makeup. It is also true that these voters are less likely to see the police as being at fault in cases of brutality.”

Trump, of course, has no chance of winning Illinois. Our state hasn't gone to a Republican since 1988, and Trump trailed Clinton by nearly a million votes here in 2016. If he chooses to run Nixon's law and order campaign, though, we may see footage from our city in his 2020 ads.