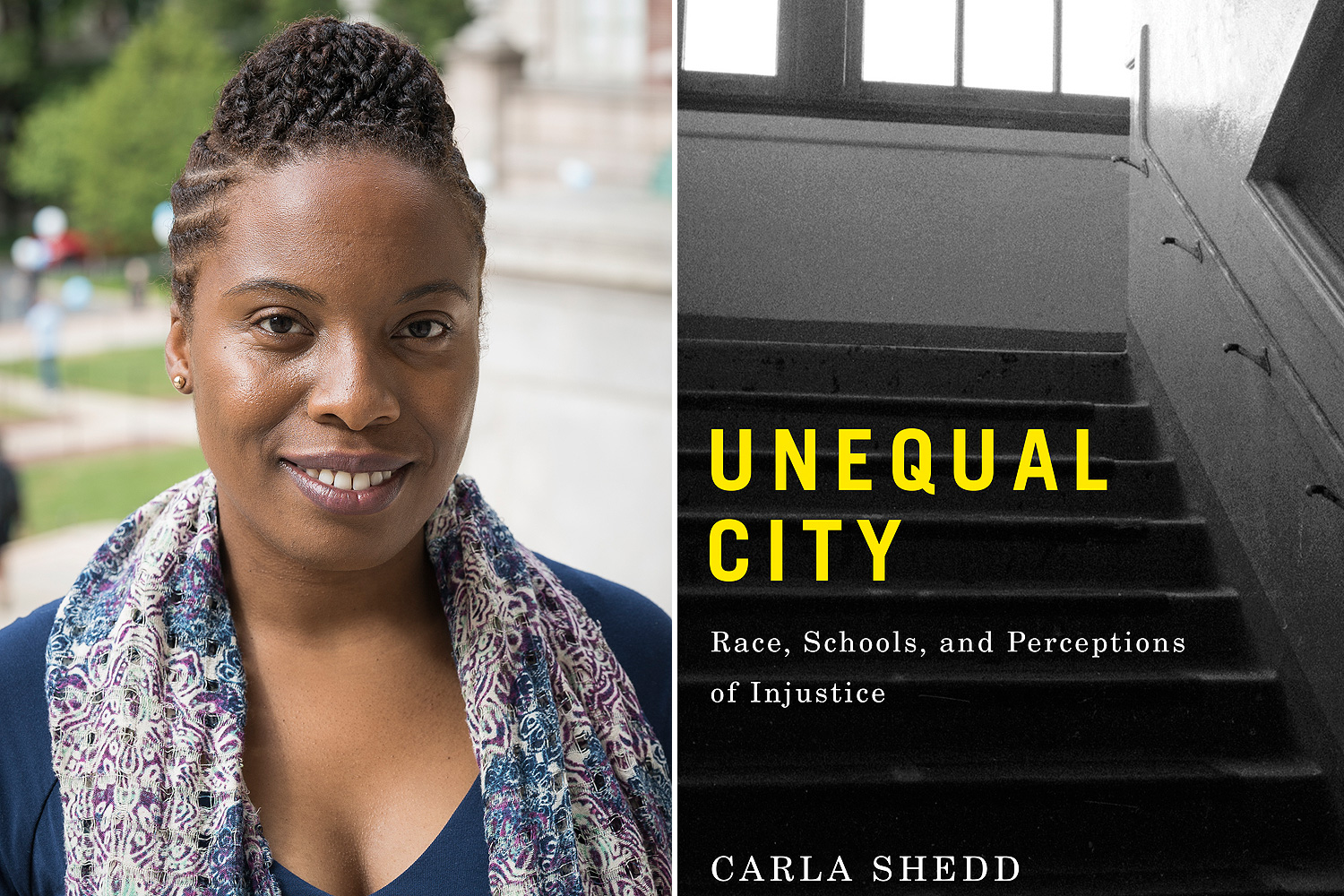

Carla Shedd, an assistant professor in sociology at Columbia University, first came to Chicago as a kid from Jackson, Mississippi, to visit family. She returned again, after graduating from Smith College, to study it, as a Ph.D. student in sociology at Northwestern, where she learned to navigate the city with the advice of her family and the tools of a sociologist.

The result was her new book, Unequal City: Race, Schools, and Perceptions of Injustice. Shedd talked to a sample of 40 students drawn from four schools: the highly selective Walter Payton Prep, Lincoln Park High, Tilden Career Community Academy in Canaryville, and Harper in West Englewood, the last of these a focus of a well-known This American Life series.

Shedd wanted to add dimensions to the data, in particular how students navigated what she calls a "universal carceral apparatus"—police on the street, police outside the schools, police and security guards within the schools—and how their experiences differed by place.

I spoke with Shedd about what she learned from Chicago's public schools and its students, and what they are learning from the city and its institutions.

How did the book start?

I started at Northwestern in the early 2000s doing my graduate work in sociology; I came to the project knowing I was interested in prisons and inequality. My advisers said, Hey, we have questions about this big survey of Chicago school kids. Do you want to work on that data? [This was a 2001 survey by the University of Chicago's Consortium on Chicago School Research of more than 20,000 CPS students that measured, among other things, their perceptions of social and criminal justice.]

I started working, but I still had questions. You have this broad base of information about Chicago public school kids, across many different areas—race, neighborhood. The surveys don't really tell you how kids are experiencing those very different contexts. I saw large patterns—there are kids getting arrested, there are kids who are thinking about race and opportunity, there are kids who are dissatisfied with the level of services offered by police. This gave me the opportunity to get the narrative behind the numbers.

What surprised you about their answers?

It was eye-opening for me to see across these different school spaces and learning that the young people attending these schools also had their frames of knowledge expanded, especially if they came from a low-resource neighborhood to a high-resource school. They saw different people, different modes of interaction, which is in contrast to the kids who stayed on the South Side, went to school on the South Side, and really protected themselves, saying, "I don't leave my block, I don't leave my neighborhood unless I have to." They don't get as much of a comparison of how other people's lives are.

You say that there's a "protective" element of segregation, where a student who's living in a segregated community, in a segregated school, is sheltered from the idea of inequality. I don't think we think about that unless we're hearing it.

A sociologist named Al Young, who studied an older group of young men on the West Side, started thinking through this first. Ask these men about discrimination, and those who were very marginally connected to the world outside of their neighborhoods couldn't say anything concretely. They'd think, I'm just failing individually.

I'm looking at young people in a very similar predicament, and their vantage point is outside their window. I interviewed one kid and asked, "What do you think about police in your neighborhood?" He said, "I think they're fair. When I look outside my window I see black gangbangers, I see people doing things they shouldn't be doing." Whereas the kids who move across these boundaries of race and geography, they're saying, "Wow, the police downtown, they wave at people and give the thumbs up. They don't do that to me. They actually go in the shops and buy stuff. These aren't things I see in the South Shore."

The protective piece is so key. A kid asks, "Don't the police stop everyone?" If you shatter that and say, "No, it's actually just in your neighborhood," or "No, it's people who look like you," what does that do, if they feel like they can't really respond against it, or change that reality?

Some of the students you talked to were very alert to the nuances of why they might get stopped and searched by policed—nuances beyond their age or the color of their skin. At one point a student mentions that if he had a skateboard, that would mark him as innocent.

I had kids who said, "I use my 'talk to the police' voice, where I'm very proper. 'Yes, officer.'" They know how to change their language and cadence. Just changing physical appearance, or where you go and with how many people.

The biggest contribution was the gender component. Boys strategically walking with girls when they know the police will be likely to patrol them, or they see the police coming and they grab a girl's hand. It's protective for the boys, but it can make the girls more vulnerable.

And there was one girl you mentioned in your book who said she was stopped because the boys she was with were wearing baggy pants. She was aware of that kind of nuance.

At such an early age. These trajectories don't start at 18, 24, or 30. This is starting at 13, 14, and 15—how young people are learning about how the world works and responding to their new selves. They're coming into adolescence.

One thing you wrote that struck me is "police encounters mark a premature exit from adolescence." How does that work?

Phil Goff, a professor of social psychology at UCLA, shows in his work that in estimations of age across race and gender, black males are usually given four years on top of their actual age in assessments. So when it comes to looking at someone under the guise of criminalized suspicion, younger and younger black kids are caught under that same gaze. That's one piece where they say, "I have to learn that I can't run and race with my friends, since I might be seen as running from the scene of a crime." Or, "I have to be careful about how I use my body in public spaces."

Think about all the opportunities adolescents have to figure out who they are and try different things. These kids don't get that same freedom to do that. To try different looks, to range farther from home, to be around different types of people. That's not a mark of their adolescent experience, and it ages them.

In my estimation, it makes them skip that step of exploration, because there are consequences to stepping outside of those boundaries, or perhaps being received in a certain way by authoritative figures in what could be free spaces, like in school or particular neighborhoods.

Which runs counter to trends among middle-class and upper-middle-class whites, where there's been a trend to extend adolescence.

It's a different line of being able to try things, being able to fail, having a safety net. These kids don't have the same support structures, the same sort of second chances other kids are given. The extension of adolescence into what's called "adultescence." That's a great privilege to have that, to have a support structure that's able to accommodate it.

It reminds me of the kid in Texas who built the clock and got arrested for it. Some tech guy I know said, “You know, I was that kid, and my teachers trusted me—gave me the keys to the AV cabinet. Even though I could mess things up.”

That's learning. That's a part of the experience—for some. That's what's key in the book. That's what I want to work on: How do we change the readings that people who are in control of young people's lives have of them? Teachers, police officers, school safety officers. It's not always a bad story when the kids are like, "This security guard sees me as a person, they look out for me." They might tell me, walking down the hallway, "Oh, I can't stand police." And then the next thing I know, they're saying, "What's up, Officer Flores, let me borrow a dollar!" They tell me, "I see them as an individual, but I don't like the police."

They can sort that out. How do we do the same thing with these people who are in these critical positions, impacting how young people see themselves, experience the world, and what their outcomes are?

How are things different in New York?

New York has this decentralized high school system. Kids are moving all around the city all the time, and that's a part of the mode of New York. It's very different from Chicago kids, who may never go downtown if they live on the South Side or the West Side. New York kids are a bit more mobile, just by the nature of the way the city is designed.

That's really interesting to me, in the context of Chicago neighborhood schools being in something of a decline.

Kids show up across the city for school in New York. In Chicago you have very stagnant racial lines, and gang lines on top of that, and class-based lines. It's so much more complicated to navigate. And we're asking this of ninth-graders and tenth-graders. It's a burden.