With all the snow this week and the brutal cold forecast for Chicago next week, it’s no wonder so many of us are dreaming of Hawaii right about now. But if you own your home, those daydreams may not only be weather-related: in Hawaii, homeowners are taxed at about one-eighth the rate that Illinois homeowners pay.

On that basis, you could dream about 48 of the states. Illinois now has the second-highest property taxes in the nation, according to a recent report from the Urban Institute. Only New Jersey had higher property tax rates as of the end of 2012, the period covered by the report.

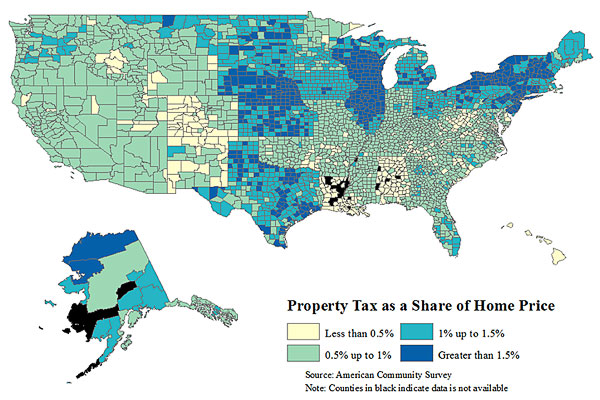

Property taxes in Illinois average 2.28 percent of a home’s value, according to the Urban Institute. In New Jersey, they’re 2.32 percent, and in lowest-taxing Hawaii, they’re 0.27 percent. (The lowest among mainland states is Alabama, at 0.46 percent.)

All the states that ranked ahead of Illinois in the 2007–11 chart saw their tax rates go up in 2012. But the rate in Illinois went up more.

When the data is in for 2013, it’s unlikely to show Illinois stepping down from second place, says Brian Costin, director of government reform for the Illinois Policy Institute. In fact, he predicts that Illinois is on its way to eclipsing New Jersey on property tax rates.

“New Jersey is going up at a slightly slower rate than Illinois,” Costin says, “so in a couple more years like this, we could be number one. But it’s not a number one that you want to be.”

We’ve been moving up. Back in 2005, Illinois property taxes ranked seventh in a report published by the National Association of Home Builders. Then we were sixth during the years 2007–11, for which the Urban Institute’s report gives a multi-year average (see pages 11 and 12 of the pdf).

What’s moving us up the list? Home values are down but taxing bodies’ appetites are up, as Costin sees it. Illinois home values fell farther and are improving more slowly than those in many other states. The latest Case-Shiller index data, which came out on New Year’s Eve, showed that while home values in the nation’s ten major cities have recovered, on average, to June 2004 levels, they’re only back to February 2003 levels in Chicago. At the same time, Costin says, “most local taxing bodies do the maximum increase they can do under the law each year.” Lombard and Lake County are notable exceptions, he says; both have reduced their rates.

When they’re asking for more total dollars in taxation on a smaller pot of aggregate home values, the tax rate is what goes up. It doesn’t necessarily mean that the amount of tax you have to pay goes up, as Cook County pointed out earlier this year.

Nevertheless, to some eyes, it’s the rate spike that that stings most: taxing bodies are asking for more of a share on your asset, even though that asset’s value has dropped. Fast-rising home values during the late, lamented boom economy of the early 2000s “lulled people into a false sense of security,” Costin says. “They accepted increases in property taxes because they thought, ‘I’m making out really well with the value of my home.’ ”

Now, he believes that “our property taxes have gotten so high that it’s having a negative effect on our housing market.” He points to reduced demand, as evidenced by a rising number of people leaving the state. Moving to Indiana—where property tax rates are less than half those in Illinois, and the cost to buy a house is much lower, as well—becomes more appealing, he says. That’s especially true for senior citizens and others who don’t have kids in public schools and so don’t feel compelled to pay high taxes to cover the schools, Costin says; as much as two-thirds of your property tax bill goes to school districts.

There’s another way that Costin sees property taxes hurting the real estate market: corporations that are looking to relocate may consider not only their own potential tax burden but the taxes their employees will pay. Companies that opt to leave Illinois (or if those that were considering coming here choose some lower-tax state), they reduce the demand for homes here, too.

In related news, Allied Van Lines reported Monday that Illinois is the state with the second-highest rate of households moving out. Last January, we were also number two in a similar report from United Van Lines, an annual report that will be updated this week. Number one in that report? New Jersey, the only state that tops us on property taxes.