By the mid-20th century, America’s list of great restaurant cities ran to, perhaps, three: New York, San Francisco, and New Orleans. But beginning in the 1960s and ’70s, Chicago muscled its way on — not because we copied other places, but because we were so much ourselves. At a time when the city was synonymous with the stockyards and steak, Chicago chefs turned that around and became world-famous figures known for their creativity and innovation in devising dishes and theatrical dining experiences.

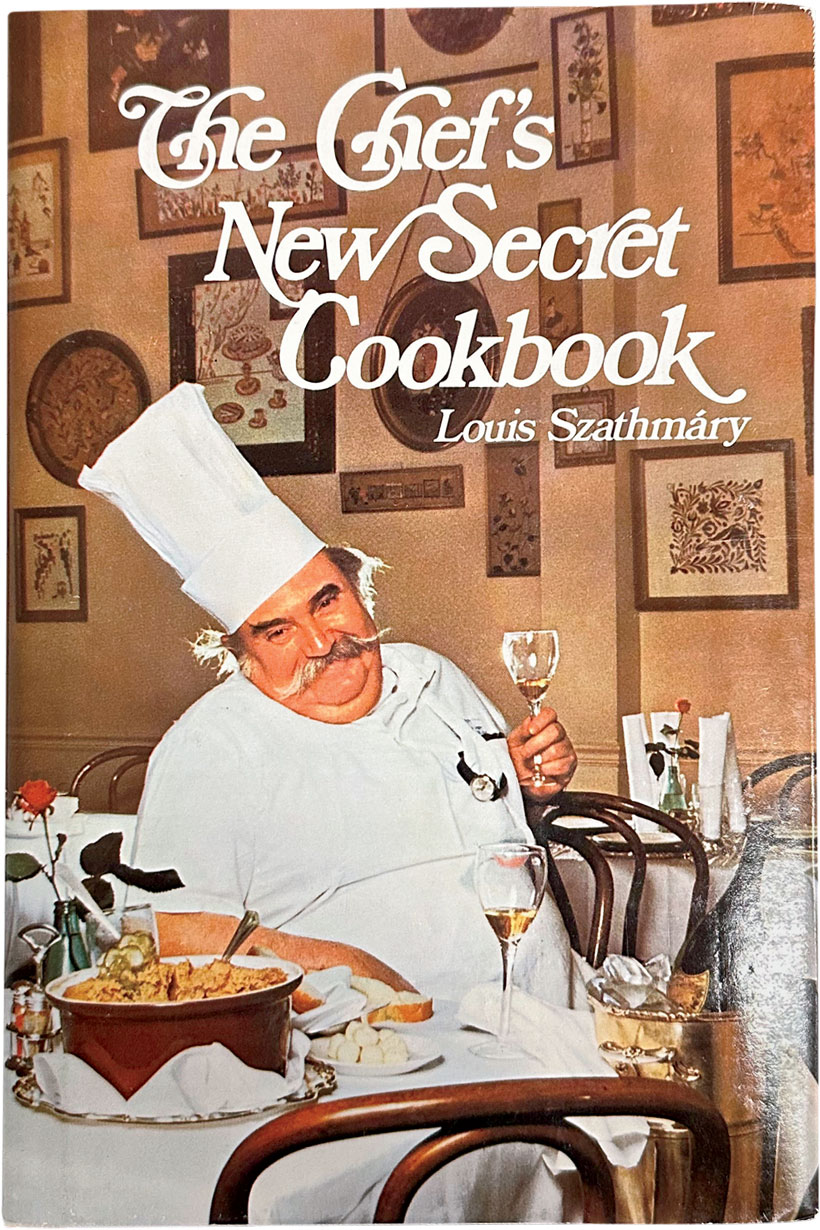

The forerunner of that movement was a man named Louis Szathmary. His storefront restaurant, the Bakery, broke the mold of fine dining here by incorporating European influences and inventive cuisine. Round as Santa Claus and with an extravagant flowing mustache, Szathmary (pronounced ZATH-ma-ree) looked the part of a chef as surely as the Marlboro Man looked the part of a cowboy — and it was just as much a self-created image as any adman could have concocted. Born in Hungary in 1919, Szathmary earned a doctorate in psychology but learned to cook in the Hungarian army and wound up in a succession of refugee camps at the end of World War II.

In 1951, he immigrated to the United States, finding what work he could as a short-order cook in New York City. Through the ’50s, he made a living as a chef and as a food scientist, working for major brands like Armour and developing Stouffer’s frozen food lines. He moved to Chicago in 1959 as Armour’s manager of new product development, and with his third wife, Sadako “Sada” Tanino, a Japanese American who had been interned during World War II, reinvented himself in the image of a classic European chef. In 1963, the couple opened the Bakery in Lincoln Park, a neighborhood best known at that time for its gang activity. The Szathmarys eventually bought the building and filled its upper floors with Louis’s massive collection of culinary books, which grew to some 45,000.

The shabby-genteel restaurant quickly became a hard-to-get reservation and was frequented by celebrities. Chef Louis himself became Chicago’s first modern celebrity chef, through his newspaper columns, the books he authored (notably, 1971’s The Chef’s Secret Cook Book), and TV appearances with talk show hosts from Mike Douglas and Dinah Shore to Phil Donahue and Oprah Winfrey. Within a couple of decades of the Bakery’s opening, Lincoln Park would become Chicago’s most popular neighborhood among yuppies, and Chef Louis was the man who taught them how to eat.

In this adapted excerpt from the new book The Chicago Way: An Oral History of Chicago Dining, those who knew the restaurant well tell the story of Chef Louis and the Bakery in their own words.

I“It wasn’t pretentious, it was real”

The Nazis had killed Louis’s first wife — she was Jewish. He went down to 90 pounds during World War II, almost starved to death between the Nazis and the Communist takeover. Talk about a survivor, coming here literally with hardly any money in his pockets. He faked his way into the restaurant business.

His brother, Géza, was already here and got him a job cooking for Jesuits [in Norwalk, Connecticut]. He could barely speak English at the time. One day, the Jesuits asked Louis, “Can you make dessert?” Louis didn’t understand. He walked into the back, looking in the storeroom for a can that said “dessert” on it.

Sada was going to the University of Chicago before she was forced into the internment camp. In the 1950s, after the war, she ended up opening the most prestigious hair salon in Chicago. It was called Kaye-Sada. She would have all these Gold Coast women come in there. They would have to walk past all the women who were waiting, so everybody could show off their fur coats.

Louis worked for Armour. So he went to Chicago for some meetings. He ended up staying at the Drake, and Sada’s beauty salon was next to the Drake. Eventually he was working more in Chicago than anywhere else. They met somehow and eventually got married. They opened the Bakery to bake for airlines: little snacks, basically finger foods — pogácsa in Hungarian. Because their two Hungarian workers were mostly drunk, they only made about 800 of these little biscuits a day. Sada said, “We are going to go bankrupt.” So they started to open for little dinners. Just four or five tables. It was a difficult start, but they took off. Then they bought the building and expanded, expanded, expanded. Both of them were extremely savvy, hardworking.

Sada was very, very smart, and she was a tough little cookie. She told me she was Louis’s “editor,” in that he had tons of creative ideas for the Bakery that he would run by her, and she would guide him into which ones to use and which ones to toss.

Louis had opened the Bakery in what was a funky neighborhood at that time, Lincoln Park. He smartly picked it and bought the building because he could afford it. A 50-seat restaurant. It immediately gained a reputation as being the spot to eat out in Chicago at the time. He used to do 600 covers a night, had a line a full block long of people wanting to get in, into the ’70s.

He was in a cool space in an unexpected area. Lincoln Avenue at that time was seedy and dumpy. Who was going out to dinner there at a really nice restaurant? Nice restaurants were downtown.

“It represented a kind of creative but also traditional gourmet dining. It was the restaurant in Chicago that Gourmet magazine would have known about.”

He had three rooms where you would dine, because that was how whatever had been in the building before him was designed. He just made it work. One of the rooms had a sink in it. We would scoop up the dirty dishes and rinse stuff right in the dining room. Another room had a refrigerator case, where he kept his cakes. He had shadow boxes hanging high up on one wall. They had lobsters in them, and one was the biggest lobster I’d ever seen, like from a monster movie. When they were about to put it in the pot, Louis had his back to it, and it was trying to grab him. Somebody screamed, because it could have killed him. Louis turned around and shoved a broom handle at it, and the lobster cut the broom handle with its pincer. So that was that lobster hanging there. Louis’s furniture was secondhand Salvation Army, literally. He’d buy stuff from thrift stores. The chairs kept breaking when Louis came downstairs and sat. The silverware was all mismatched — it was secondhand but nice. And everything was covered with white tablecloths. There was an air of elegance. It really wasn’t elegant, but there was something about it — this old building, and his personality shone through like something you’d see in Europe. It wasn’t pretentious, it was real.

One day I said, “God, these chairs are uncomfortable.” Louis goes, “François, that is not a chair. It’s a 90-minute moneymaker.” He had figured out that the chairs after 90 minutes would hurt your butt so much that you would want to leave.

There was no written menu of any sort. The waiters would come around to the tables and recite the entire menu to the guests. Everything was French service: All the food would come out on platters, and the waiters would silver-serve it. Louis was very good with the guests. He would greet them when they’d arrive. He’d let them enjoy their dinner and then come out halfway through to see how they were doing.

It represented a kind of creative but also traditional gourmet dining that was then popular at the high-end restaurants. It was not the kind of French restaurant where there is a lot of froufrou — decorations, wallpapers, and wall sconces. It was a more sedate experience. It was the restaurant in Chicago that Gourmet magazine would have known about.

II“He was more of a librarian-researcher than a cook”

It was a five-course meal. Everybody started out with the pâté, then it went to soup and salad, then the main course, then dessert. Dishes on the main stage were the beef Wellington, of course, and the roast duck with a cherry sauce. You can’t get more classic than that. On Fridays, Louis did his version of bouillabaisse, and then he had roast pork that was stuffed with a Hungarian sausage. The pâté was Louis’s little joke with the richer clientele, because 50 percent of the ingredients were pork snouts — this super-humble peasant ingredient. I’ve never again worked in a restaurant where I was roasting or braising like a hundred pounds of pork snouts. A five-course meal at the Bakery when I was there [in the 1980s] was $23. Louis would always tell me, “I’m not here to make money. This is a school for people who work here.” And he felt like it was almost a community service for the people who ate there. You know you’re coming to this institution, and you know you’re going to have this experience. Here’s the admission fee.

He served beef stroganoff because he needed to do something with the part of the tenderloin that he couldn’t make into Wellington. Everything went someplace. The trimmings from the chicken were in the goose and the duck, while he rendered that fat and used it to make the pâté. Some of it also went into the Wellington. Then the cracklings from when he rendered it got served to the employees as a treat with breakfast. I’m sure part of it came from his Hungarian cleverness, but part of it came from the fact that he spent some time at Armour, where the old saying goes, “We use everything but the squeal.”

He used all these canned sauces from Sexton Foods [a Chicago-based wholesale grocer] — these large industrial cans. He was a food scientist who had worked for different companies. He used some really commercial methods in his food — whatever worked. He brought it all together and made it his.

Almost everything in that five-course menu had something sweet to it. There was a salad with a sweetened vinegar. The beef Wellington came in a very sweet currant Cumberland sauce. And then of course the desserts. Here was Louis, his background originally as an industrial psychologist. He understood what made restaurants tick, and what people like, the flavors that we perceive — sweet, sour, salt, and bitter. Sweet is the one that we initially all gravitate to, isn’t it?

I don’t even know if I should admit this, but I did not like his beef Wellington. People loved it, so it might have been just my taste, but I didn’t like whatever ground meat he put on top of it.

We had a very nice wine selection, limited. Very limited cocktails. I don’t think we had space for it. We had Charles Krug Cabernet Sauvignon, which is my favorite wine from ’85 and ’86. You could buy that in the restaurant for 18 bucks. But people didn’t know what to do with those wines. Sometimes they had a sip and left half a bottle on the table. Happy for the waiters, because Uncle Louis was very liberal. He’d say, “OK, at the end of the night, you can have it if they don’t take it.” He also had a brown-bag policy. It was not legal 100 percent, but he said if they paid for it and they want to take it, they are grownups.”

He was well read and had a memory. He just knew something about everything and liked to go on for hours talking about food. That kind of knowledge, I think, is not as prevalent in today’s chefs as it was back then.

Louis was always inviting Hungarian literary people, basically hosting them for a week or two. And every summer we had Hungarian summer students. They came to do research on food psychology.

I never saw him cooking in the kitchen. He’d be upstairs, developing and testing recipes, reading his cookbooks.

He was more of a librarian-researcher than a cook. He never grew up with an apprenticeship. So he complemented or embellished his knowledge by researching and trying to understand different dishes. He created recipes based on recipes that he read. He figured out creatively how to combine these to make the best result.

United Airlines — I could be wrong about which airline — wanted Louis to design airplane food. We had like 20 execs from the airline fly in for a tasting. We had the teeny trays that you have on an airplane and made 20 trays each of like 10 different dishes for them to try. He always was doing stuff like that. He did the food for the first space shot — the food in the tubes. All kinds of cool stuff.

III“A showman with substance”

For the most part, chefs didn’t have personalities back then. They were surly at best. They stayed in the kitchen. And here comes Louis. He’s got the iconic look. He’s got the belly of a baker. He’s got this mustache that you’ll never forget. He was jovial. He was a presence. He was friendly. He was fun. He was a great self-promoter before most people were. That certainly set him apart.

He was his own best PR person. The reason for the Bakery’s success was that he knew how to promote himself in a very meaningful way to the press. He was a showman with substance. He ended up writing a column for the Sun-Times for years. It was syndicated.

Louis wielded immense power on the restaurant scene in Chicago. I remember we got a negative review. I can’t remember if it was the Sun-Times or the Tribune. The writer went on about how shitty the food was, that it was completely dated. He made this huge point about the tomato bisque soup, that it was god-awful. Well, Louis had never served tomato bisque soup in the history of the restaurant. So he was just completely livid — not about getting a bad review but that this guy had fabricated this. Louis pretty much got him fired over it.

“Chefs didn’t have personalities back then. And here comes Louis. He’s got this mustache that you’ll never forget. He was jovial. He was a presence. He was a great self-promoter before most people were.”

A personal friend of Chef Louis who came in on a regular basis was Sir Georg Solti, the music conductor of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. He was Hungarian, and he was a true gentleman.

Louis had some notebooks from some of the celebrity parties that he hosted. One of the people who had him cater was Frank Zappa. And in this notebook, there was a picture of this marzipan cake in the form of a naked lady that we made, with Zappa’s head between her legs.

Zappa and Louis were friends. Whenever he came into town, we would get backstage passes to his concert, and he would come and have this crazy party at the Bakery. It was the stuff of legend when you worked in that kitchen. One time Louis baked a blackbird pie that had 50 live blackbirds inside. When they cut the crust, the birds went flying all over the place. They totally trashed the restaurant. He had to repaint it for the next morning.

One night Harry Truman’s daughter, Margaret, came for dinner. She knew Louis because he’d catered for her in New York. The story was that back then he didn’t know who she was at first. She had placed the order, and then while he’s cooking in her ritzy apartment, at the last minute she said, “Oh, my father’s going to join us for dinner. Can you make one more serving?” It’s like an assembly line, but he started making one more, and he’s all flustered, and this little man comes into the kitchen: “Oh, could I get a glass of water?” Louis said, “Sir, I’m very busy, could you get your water out there?” And the guy said, “I was president of the United States. I’d think I could ask for a glass of water.”

I was thinking about two days in a row back in ’85. When the Lyric Opera had an opening for an opera, everybody would come to the Bakery afterwards. One day was that. Pavarotti is there, all these super-famous people. I forget what, but one course was something very fingery and messy, so Louis put down Wet-Naps, and people were kind of looking at him like they’d never seen one before. I think some people thought they were mints or something. The next day, Louis did another party — a law school graduation. So here’s all these young lawyer wannabes. And Louis served a silver finger bowl with a slice of lemon and a little water to rinse your fingers. I can’t tell you how many people drank it like lemonade.

IV“He had a volatile character”

Louis was very caring about people. He would have his apartment complex filled with refugees he brought over. They were all these educated people who had fled Eastern European countries. They’d been teachers and accountants. They would come with nothing. And he would put them up in his apartment and give them a job working in the restaurant. The work ethic of these Europeans, these teachers and accountants — they didn’t think anything of cleaning the tables and mopping the floors. And then he would help get them settled in better jobs.

My father came to America in 1970. He had a brother who lived in Chicago. And so a good friend of Louis who was also Hungarian said, “You can maybe work in his restaurant and make a little extra money.” So he met Louis and Géza, and they just totally embraced him. He became known in the Bakery as the gombó király, which means the “dumpling king.” When I came, we both moved into the Bakery building. I became a dishwasher. Every night, 600 to 800 dishes. And then I started at the School of the Art Institute. Well, you need to make money as a student. So Louis promoted me to waiter.

My father was Hungarian, and my folks were friends with Louis and Sada. As a kid, I spent my Saturday mornings hanging around the Bakery. When I was 12, I would cut out Louis’s newspaper column from the Sun-Times, and, before that, the Daily News, and file them away so that he had copies to give people. In his cookbook library, he had a lady helping him catalog and sell all of his extra copies. I helped type up the cards for the books and pack them into boxes. If I was left unsupervised for a couple of minutes, I might sneak into the rare book room, which is where he had all of these 14th- and 15th-century illuminated manuscripts. Then I graduated to answering the phone, taking reservations, and helping the staff accountant take inventory of what was sold the night before. After that, I worked as a busboy.

When I was 20, Lerner Newspapers hired me to work part-time while I was in school, and they gave me Louis’s columns to edit. What did I know about editing? I just took the Hungarian-ness out of them and made them sound like English. He had colorful stuff to say, so it was like polishing a diamond. Then I decided I wanted to meet him. So I ate at his restaurant. He became like family to me. He had me over for media events, and I’d go to events at his home on Wellington. I ended up working for him as a busboy. I had him over a couple of times to my place to eat. How many people have the top chef in Chicago to their place to eat? I just thought, Well, nobody invites him because they’re too scared. I served him lox and bagels and cream cheese and bought a dessert from Kenessey [a Hungarian restaurant and bakery in Lake View]. He loved it. He said, “I know lots of people, but I don’t have many friends. You’re my friend.”

I went to the New England Culinary Institute. My second year, Louis came and spoke. He was a really intense person, and everything he said in that speech just solidified that I wanted to be a chef. So I struck up a friendship with him through letters. I was going to go work for Jovan Trboyevic at Les Nomades. He was close friends with my father. But I also happened to be calling the Bakery for a reservation, and whoever answered the phone was like, “Hold on, Louis has been looking for you.” Louis offered me the executive chef job, which was ridiculous — I was fresh out of school, and other than working for my family, I’d only worked at one restaurant. But I was completely headstrong and thought I knew everything.

He took care of his employees. He had health benefits for them — in 1970. And he had somebody cooking for the staff. It was delicious. It was like earthy, peasant food. The chicken soup was the best I’d ever had in my life. I said, “How did you make that?" He said, “Gott demn, that dish! This old lady come in and make it from bones and everything every day. I don’t know how she make it, but it’s so good!”

“Louis was the kind of guy that on one hand, you’d be crouching in the corner fearing for your life, with him ripping you a new asshole. But in the second moment, he’d be the most compassionate person.”

Louis had employee breakfast at a quarter of 9 every day. And you had your choice of scrambled or fried eggs. It was either Fridays or Saturdays they made French toast with the leftover bread from earlier in the week. It was a treat. Sometimes they put out duck and goose cracklings at breakfast. And for the Mexican staff, jalapeño peppers.

We would all sit down together like a family and have dinner at 4 o’clock. It was really the most tight-knit operation that I ever worked in in my life.

There was relatively little turnover. It was like many of the other old-school high-end restaurants where these guys just went and stayed. Some of them were making 50 grand then, and that was before anybody had the forced tip declaration.

Louis was the kind of guy that on one hand, you’d be crouching in the corner fearing for your life, with him ripping you a new asshole for something. But in the second moment, he’d be the most compassionate person you’d ever want in your corner — your advocate when you’re really in trouble. Nothing against Hungarians, but in my experience, they’re forceful people. Even when they say “I love you,” it sounds like they want to rip your head off. He had a volatile character about him. Barbara [Kuck] was his assistant. She worked with him in the test kitchen, she was his right hand. I remember a time when I came out of the walk-in during a party. Louis was sitting on the stool in the kitchen, and all of a sudden he picks up a knife. Louis is a huge guy, and he’s ambling after her. “Barbara, I will keel you.” He got mad at me one time, I forget for what. He cornered me in the kitchen, saying, “You are not my chef. You are my shit.” Lines you’re half laughing at. I don’t mean it to sound abusive. I never felt like Louis was abusing me. It always felt like your grandfather scolding you for screwing up.

Louis would sometimes erupt at Sada, as he did with just about everyone. After one eruption, Sada bluntly told him, “Louis, if you want, I can leave. Right now.” Louis shut up and immediately ordered flowers for her and apologetically took her out to dinner.

Eventually, he fired me. This is my favorite story. He’s like my uncle, so I said, “Uncle, I’d like to visit my family and take a month of vacation.” “What, how do you dare to? I’m firing you right now.” He called Sada and said, “I fired Miklos.” She says, “We only have eight waiters, including him. Usually we have 10. You cannot fire him.” He asks, “Well, when will the other staff be back?” “Two weeks from now.” “OK, Miklos, you’re fired two weeks from now.”

V“The faded gem”

When he opened the Bakery, he was considered novel, revolutionary — something new, something cool. But people’s tastes changed. Later on, I think he might have even conceded that.

He was a character straight out of the old school, one of America’s bridges to the past, in much the same way that Paul Bocuse was in France. I ate at Bocuse’s restaurant a month after he passed away. And it was like going back in time in France — dishes on his menu were dishes from the 1800s that his mentor’s mentor learned on her internship. And here it is, still on a menu, completely irrelevant in this time and day but one of those iconic dishes. Working for Louis was the same kind of thing. When I was there in the ’80s, the Bakery had become the faded gem, because the next crop of big restaurants were popping up. Louis never adapted. He served beef Wellington from day one. I think he really thought that style was going to come back. Louis became a caricature of himself in his later days, almost became a joke for the stuff that made him famous, the fact that he stuck to it. But so many people still looked to the Bakery as that special spot because they ate there as kids. It was very formative in a lot of people’s education.

Louis was the reason Charlie Trotter became a chef. Because he ate there on his prom night. When he saw Louis coming out of the kitchen into the dining room, he said, “That’s what I want to do."

They showed up all well dressed, having good food. I said, “Well, guys, I understand it’s your prom, but where is your wine with the meal?” Charlie says, “We are not 21.” Then Louis says, “You know what? It’s my restaurant. Everybody can have a sip of wine with a meal.” That’s why Charlie Trotter at some point decided to be a chef, because of the power that a chef has in the dining room.

People like that just aren’t made anymore. People look at the image of Jean Banchet as more high-end and premium, but people like Louis were really important steps in our country’s culinary development. A lot of people don’t realize all the things that he did. When I grew up, my mom used to buy this spinach soufflé — little Stouffer’s things that I would bake and get the crust really brown and slightly burnt on the top. That was Louis’s grandmother’s recipe. Louis did like five of the early, really successful dishes for Stouffer’s.

He was a benevolent dictator. Looking back, I just wish [the restaurant working] environments were that nice today. Because here’s an entrepreneur who went through hell and built a business himself. He knew what it was like to almost starve to death. He knew what it was like to suffer.

If somebody was there for any period of time and didn’t learn something from Louis, then they were trying not to.

The Bakery closed in 1989. Chef Louis died in 1996 at 77; Sada, in 2016. Szathmary’s collection of culinary books and memorabilia, valued at $2 million at the time, went to Johnson & Wales University in Rhode Island and the University of Iowa, which published a series of culinary arts scholarly works named for him. In 1990, the City of Chicago designated the alley behind where the Bakery stood as Honorary Szathmary Lane.