It took the seasoned pros at One Off Hospitality Group almost three years to get Publican Tavern, the new offshoot of their beloved West Loop meatery, off the ground at O’Hare International Airport. The project, now open in Terminal 3, presented challenges that wouldn’t even cross the minds of most restaurateurs.

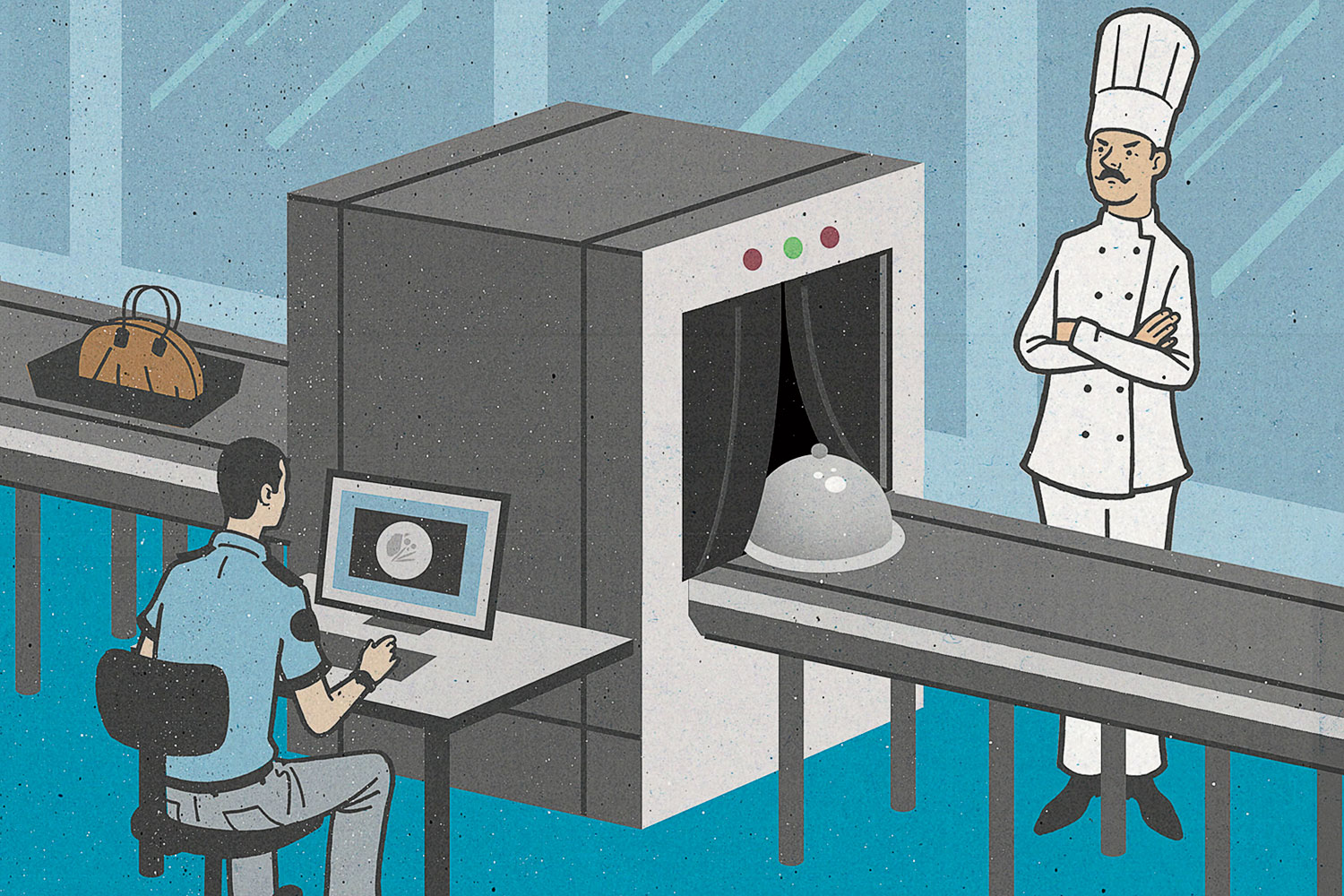

Like, say, how to improve your cooks’ knife skills when their utensils have to be chained to the counter as a security precaution. Or having to go through a TSA checkpoint every time you come to work.

One Off was first approached about opening a spot inside O’Hare by the catering contractor HMSHost in 2011 as part of a push to bring more local flavor to the airport. But the project sat in limbo—HMSHost kept pushing the launch date back—until about six months ago. That’s when work on Publican Tavern, which will occupy a former Wolfgang Puck space, began in earnest.

The most fraught questions for the kitchen team were how to translate the hallmarks of the original restaurant—the iconic roast chicken, the high-quality booze, the impeccable sourcing of ingredients—to a mass-market format and, even trickier, how to work within the constraints of airport security.

Unlike in the West Loop, they couldn’t just have their go-to farmers pull up to the back door to drop off a couple of flats of assorted vegetables or a few dozen duck eggs. The cooks at the Publican wanted to keep working with as many of their local vendors as possible, says executive chef Cosmo Goss, but every single airport supplier must undergo a strict food safety certification from the independent auditing group NSF International. Not all of the restaurant’s regular purveyors could meet NSF’s standards. For example, One Off’s own baking arm, Publican Quality Bread, worked out of a kitchen that was too small to be able to follow NSF’s packaging regulations, so Publican Tavern has had to outsource bread production to the local bakery La Fournette.

Even some Publican suppliers that did meet NSF standards weren’t able to meet the projected demand, which Goss estimates will be close to 1,000 customers per day. (The flagship restaurant sees about 350 for dinner service.) Slagel Family Farm can’t produce nearly enough birds for both the roast chicken and the chicken wings, so they’ll just provide them for roasting while the wings will come from Bell & Evans. And butchering the hens in-house, like at the Publican: Forget it. Prebutchered poultry will have to do.

Ingredient sourcing is only part of the challenge. HMSHost handles the hiring for the airport’s restaurants and simply transferred most of the Wolfgang Puck staff to the new venture, letting One Off bring in Goss and a couple of other veterans to supervise and allowing the staff to complete four weeks of One Off training. These men and women aren’t fresh-out-of-culinary-school types; many are concessionaire cooks who have been working at the airport for decades. (One of them, Pablo Baron, has been at O’Hare for 43 years.) Goss says a lot of them looked shocked when asked to peel garlic themselves instead of grabbing the prepeeled stuff from a jar.

Experience does have its advantages, though. As Goss puts it: “Are they classically trained? No. Have they been cooking eggs for years at the airport and gotten better at making them than I ever will be? Yes.”

The location is a boon, too, at least in one respect: What better way to sell lots of minibottles of Batch No. 1—the new bottled cocktail mix from One Off’s the Violet Hour—than to peddle them to thirsty travelers before takeoff?