Augustus Rose has seen a lot of weird stuff. Driven by an obsession with hidden secrets, the University of Chicago professor has climbed through city drainage tunnels, snuck into Roman necropolises, and explored abandoned islands off the coast of Maine. But the strangest thing he’s ever seen hangs in the Philadelphia Museum of Art: a giant, inexplicable sculpture called The Large Glass by the father of “readymade” art, Marcel Duchamp.

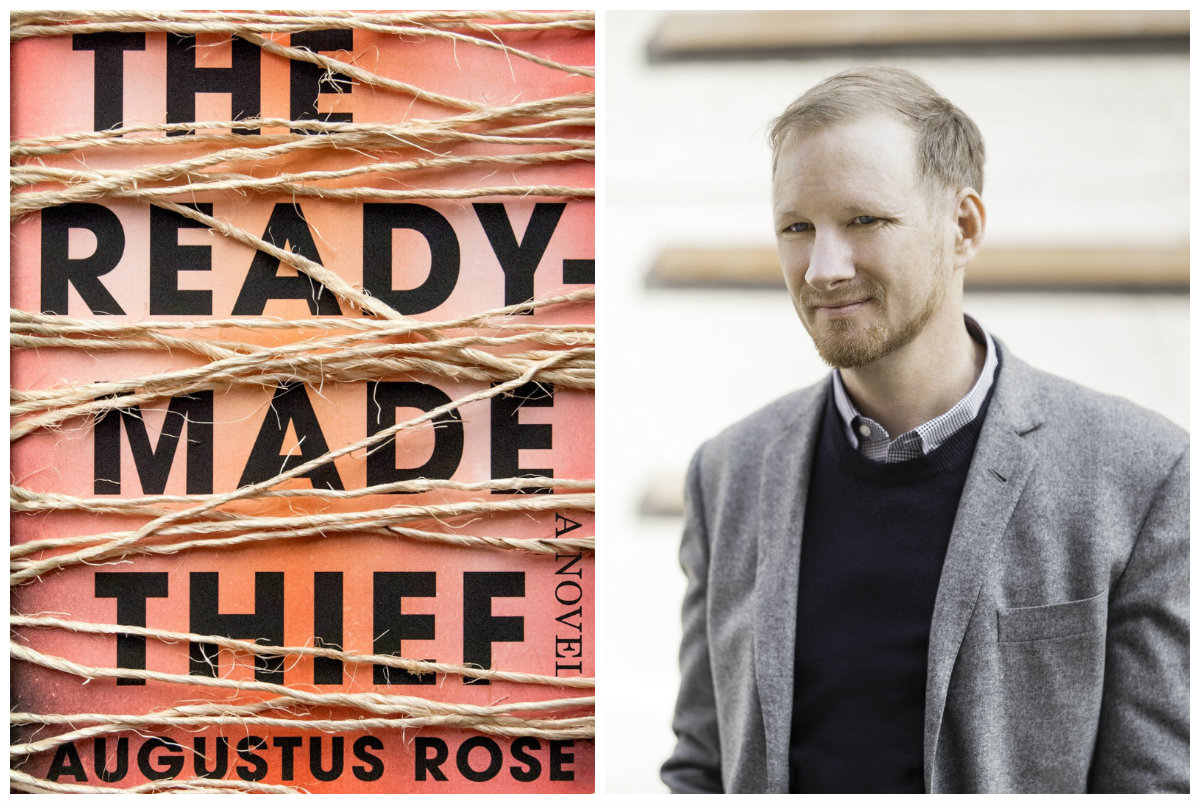

The sculpture is the centerpiece of Rose’s debut novel, The Readymade Thief (released August 1 by Viking), a literary thriller about a homeless teenage girl, Lee Cuddy, who shares Rose’s obsession with hidden knowledge. After stealing one of Duchamp’s “readymade” sculptures from a secret society, Lee discovers a 100-year-old mystery involving The Large Glass that could change history—and explain why a bunch of teenagers have gone missing.

As Rose's first book hits shelves this week, I asked him to reveal some secrets of his own.

How did you first discover The Large Glass and why did it speak to you?

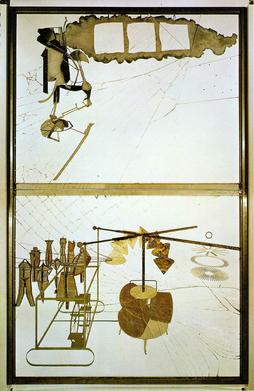

I was working in a bookstore in San Francisco the summer between high school and college, and I remember hiding away in the sorting alcove and getting lost in a book of Duchamp’s work. There’s a photo of The Large Glass, with a man staring up at this towering pane of shattered glass with a strange system of mechanical-yet-organic forms. It was such an inviting mystery. I know now that the work is meant to represent a frozen moment of time from a larger narrative (like a single frame of film from a movie), and so maybe part of me realized there was a story to uncover.

Do any works of art in Chicago have a similar effect on you?

Chicago has a ton of singular works that give me goosebumps just to stand in front of, but one oddity that stands out for me in particular is Ivan Albright’s Picture of Dorian Gray at the Art Institute. It’s a wonderful, grotesque portrait of Dorian Gray in full rotting glory that was commissioned for the 1945 film adaptation of the novel, and I remember seeing the movie multiple times on TV as a kid.

I loved the movie, but a movie has no “aura,” simply because it’s a reproduction. So when I first stumbled on the painting in the museum I was struck by the contrast—how powerful and affecting it is just to stand in front it, this thing that I had seen reproduced on TV so many times before.

Why does Marcel Duchamp still matter 100 years later?

I’ve been so fixated on him for so long, but since selling the novel, I’ve done a kind of roaming informal survey on what people know about Duchamp. I usually get back the look of someone diving deep into their memory banks, then resurfacing with some version of: “He was an artist, right? The urinal guy?” And while that is 100-percent correct, it doesn’t scratch the surface of Duchamp’s influence on the world of art.

I think the entire landscape of art would look different if Duchamp had never put his mark on the world. All conceptual art exists in his shadow. He allowed us to see art as a cerebral act as much as an aesthetic one, to approach art as a way of thinking as much as it is a way of seeing. Doing this put the viewer into the work in a way that I don’t know had ever been conceived before. Duchamp said: “The artist performs only one part of the creative process. The onlooker completes it, and it is the onlooker who has the last word.”

To him there is a kind of spark that ignites when the observer comes into contact with the work of art, and it’s in that spark that meaning is generated. And so for every viewer the meaning of the work (and therefore, in a sense, the work itself) might be something different.

Why are people obsessed with mysteries and hidden knowledge? Isn’t ignorance bliss?

I think ignorance, without the yearning for knowledge, is just boredom. But combine ignorance with the quest for knowledge, be it the process of solving a mystery or of understanding the secrets of the universe, and there’s a great pleasure in that. Once we gain the knowledge we seek, a kind of disappointment often settles in, because it puts us in a place of answers, and questions are almost always more exciting and interesting than answers.

This is actually what I love about writing novels—not knowing where I’m going. It’s the reason I don’t outline. There’s a hunger and curiosity that drives me to see how things will turn out. And generally speaking, a satisfying novel doesn’t just end by answering all the questions it’s brought up, rather it tends to open up into a place of more questions.

Have you ever stolen something? Or felt the urge to?

Sure I have. Mostly as a teenager. But I’m not proud of any of it, none of it even makes for good stories. My character, Lee, steals out of compulsion, part of a need to connect to people, and I have much more sympathy for her. I was just a dumb kid who thought I had nothing better to do.