In 2004, Karen Ami began teaching classes on mosaics out of a small storefront in Lake View. At the time she opened the unassuming school, located just across the street from the artist's house, no other arts organization in town, including the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, gave lessons on the medium.

"People told me, 'It's a really old art form,'" says Ami, who received her MFA in sculpture and ceramics from SAIC. "While I was at school, I wanted to study mosaics, and they told me that I had to go to Italy. Long story short, I started the school because I wanted to learn about this."

The Chicago native quickly established her initiative as a nonprofit arts center and named it the Chicago Mosaic School — the only one of its kind in the United States. It attracted so many students that Ami eventually moved to a larger space in North Center. "There was a huge response through word of mouth, and a shared enthusiasm for learning about the mosaic art form," she says.

Now, 14 years later, CMS has found yet another new and much larger home — 1127 W. Granville Ave. in Edgewater, just a stone's throw away from the Red Line. It occupies the first two floors of a recently finished building named the Cochran, which is mostly filled with rental apartments.

The move to this larger property occurred due to unfortunate circumstances. In early 2017, the school was forced out of its North Center building by the developer, Ami says. But then 48th Ward alderman Harry Osterman invited her to migrate her project to Edgewater — she accepted. It took 18 months before the Cochran was ready for its new tenant, but the school kept its presence just a few doors down, in a temporary space.

CMS has hit the ground running its new residence. Enrollment is open for its dozens of classes, which range from intro-level courses to intensive stained glass lessons to classes on ancient techniques. The school also welcomes students of all ages and hosts youth and family workshops; Ami invites visiting mosaicists from around the world to teach unique seminars throughout the year. And while its main focus is mosaics, CMS offers a broad range of creative opportunities: Teachers lead classes on sculpture, figure drawing, frame making, and more.

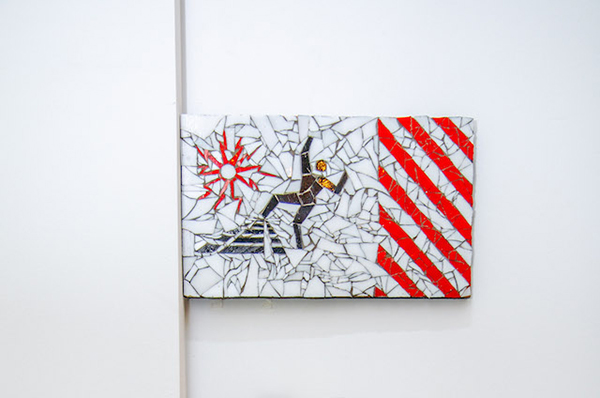

Passersby can peer through the Cochran's glass facade to glimpse the school's Gallery of Contemporary Mosaics, which hosts temporary exhibitions of artworks by students and faculty. Currently on view is the inaugural show, DEBUT, which opened on July 13th with mosaics by 15 contemporary artists from around the world (local makers Rebecca Baruc and Casey Van Loon are also included). The pieces showcase a variety of material, from Scottish slate to traditional Italian smalti to Byzantine glass. CMS, in fact, acquired the largest inventory of Byzantine glass in the country in 2012, leftover from the construction of the Cathedral Basilica of Saint Louis. The glittering fragments are displayed in the main studio, like candy in a large wooden cabinet.

In addition to its airy gallery and main studio, CMS houses 11 artist studios as well as the city's only mosaic-tools shop, Tiny Pieces. Since Ami has more space to work with, she plans to engage with local communities on larger art projects. The school has previously worked with independent artists to create public artworks as well as with Chicago Public Schools to produce sustainable mosaics. "We've been very clear about how to make work that is tolerable to our climate," she says.

The CMS expansion not only signals the arrival of more robust programming but also reflects what some mosaic artists see as changing public perceptions toward this ancient art form. According to Ami, many mosaicists aren't recognized in the United States — but she believes that people are beginning to appreciate their work. Faculty member Lydia Shepard agrees. She says that mosaic has been largely undervalued because it's carried a certain stigma that's been hard to shake.

"I feel like mosaic has been kind of been stuck for a long time, at least in the US, in the world of craft and kitsch," Shepard says. "But I see the future of mosaic as being more widely accepted as a fine art. I think a lot of the artists who come to the school have helped elevate it into a fine art."