Ten weeks ago, Bina Mangattukattil didn’t think of herself as a writer. But the clinical social worker and West Ridge resident had a story: Growing up in Chicago in a traditional South Indian Catholic family, she converted to Islam after grad school, but she didn’t tell her parents until she was pregnant with her daughter.

Now, her play “A Beautiful Path” is part of the first-ever West Ridge Story Festival, which highlights 11 original ten-minute plays written by immigrants, refugees, and longtime residents of West Ridge. Mangattukattil pulled from her experience to write about navigating cultural boundaries as a convert and immigrant.

“It was very cathartic for me, because it’s an unspoken topic with my parents,” Mangattukattil says.

The festival is the first major project kicking off theater company Silk Road Rising’s yearlong residency in West Ridge. For the past couple months, Mangattukattil joined other West Ridge residents and students from Daniel Boone Elementary School in the company’s free Empathic Playwriting Intensive Course, through which they adapted and workshopped their narratives for the stage. The festival aims to give voice to different layers of the immigrant experience by exploring topics like religion, healing from traumatic violence, and assimilation. Directed by Silk Road Rising associate producer Corey Pond, six actors will premiere their work at one of three staged readings from December 14 to 17.

Jamil Khoury, who cofounded Silk Road Rising with husband Malik Gillani as a response to the September 11 terror attacks, says the festival is a pilot project. The company selected West Ridge because the neighborhood is one of the most ethnically and culturally diverse in Chicago and possibly the country, making it a hub for first- and second-generation immigrants. Even so, Khoury says the neighborhood can be lacking in intercultural exchange. He believes Silk Road, as one of the country’s first arts organizations dedicated to promoting Asian and Middle Eastern narratives, is primed to facilitate that dialogue.

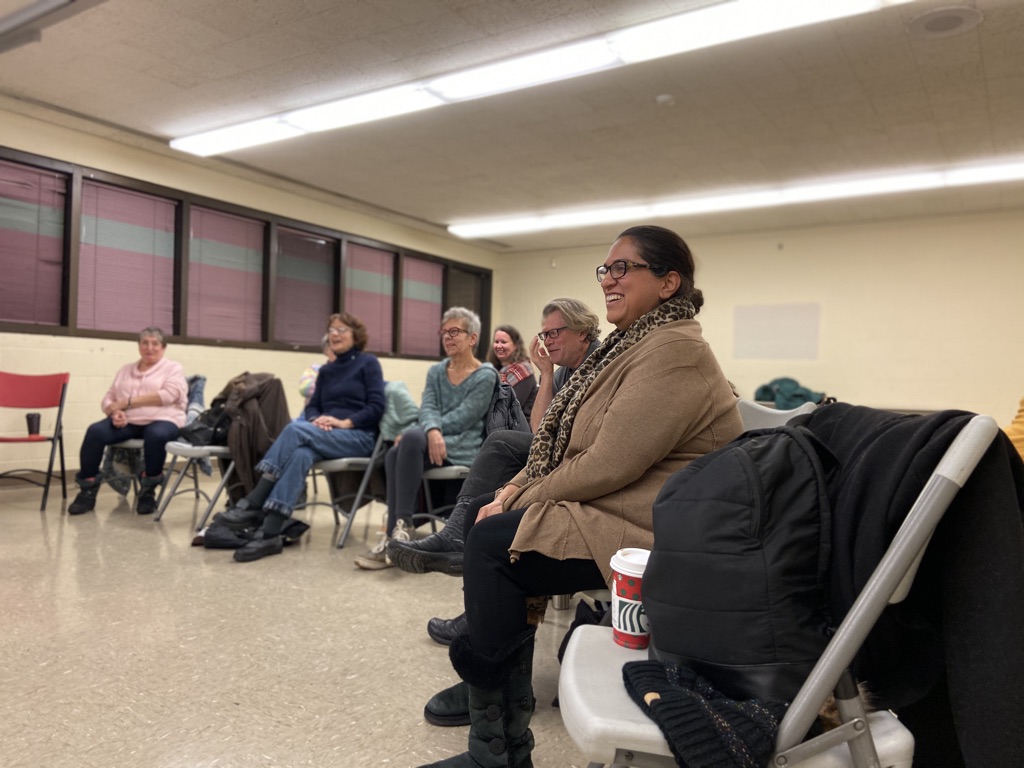

.jpg)

Photo: Michael Meade for Silk Road Rising

“People live next to each other and walk past each other on the street, [but] they may or may not patronize each other’s businesses,” Khoury says. “There is a certain lack of social cohesion.”

This year’s edition involved collaborations with 12 faith and community groups in West Ridge, all of which helped find residents to participate in the course. Longtime resident and dance teacher Phil Martini partnered with Silk Road to host festival classes and performances at the Indian Boundary Park Cultural Center, which he supervises. He likewise sees the insularity Khoury points out, especially in the Indo-Pak community and the Orthodox Jewish community, and hopes the festival will connect residents from different cultural contexts.

“These people were thrown together from different backgrounds,” he says. “Any time you have to collaborate to create, you’re going to break through preconceptions of what the other is. What I expect to see are the shared experiences that bridge cultures.”

Ultimately, the playwriting workshops were not as diverse as Khoury had originally envisioned: Mangattukattil’s writing group lost all its other participants of color by week eight due to what Khoury calls “the socioeconomic realities of the immigrant experience.” However, Mangattukattil redoubled her commitment, saying she learned how universal immigrant stories can be, especially in a polarized and often xenophobic political climate.

“The whole purpose of this project is so we can have a platform for our stories, meaning immigrant stories,” she says. “I’m concerned about the narrative about my community and so many other communities when there’s growing white nationalism. Our antidote to that is these stories. The only way you’re going to dispel hatred is through building real, meaningful relationships.”

Mangattukattil admits that while her mother knows about her being Muslim, it’s not something they discuss. It’s a struggle she’s still carrying with her, which was all the more reason to put it on paper — though the thought of her mother seeing the play is “terrifying.”

Even so, Mangattukattil is happy her story is out there and hopes other immigrants and converts will someday share their own experiences.

“I’ve never seen a play like this before. That’s part of why I wrote it, because I’ve never seen this perspective,” she says. “Representation is so important in media, film, plays, and books. And our stories need to be told by us. There’s a need for this in West Ridge.”