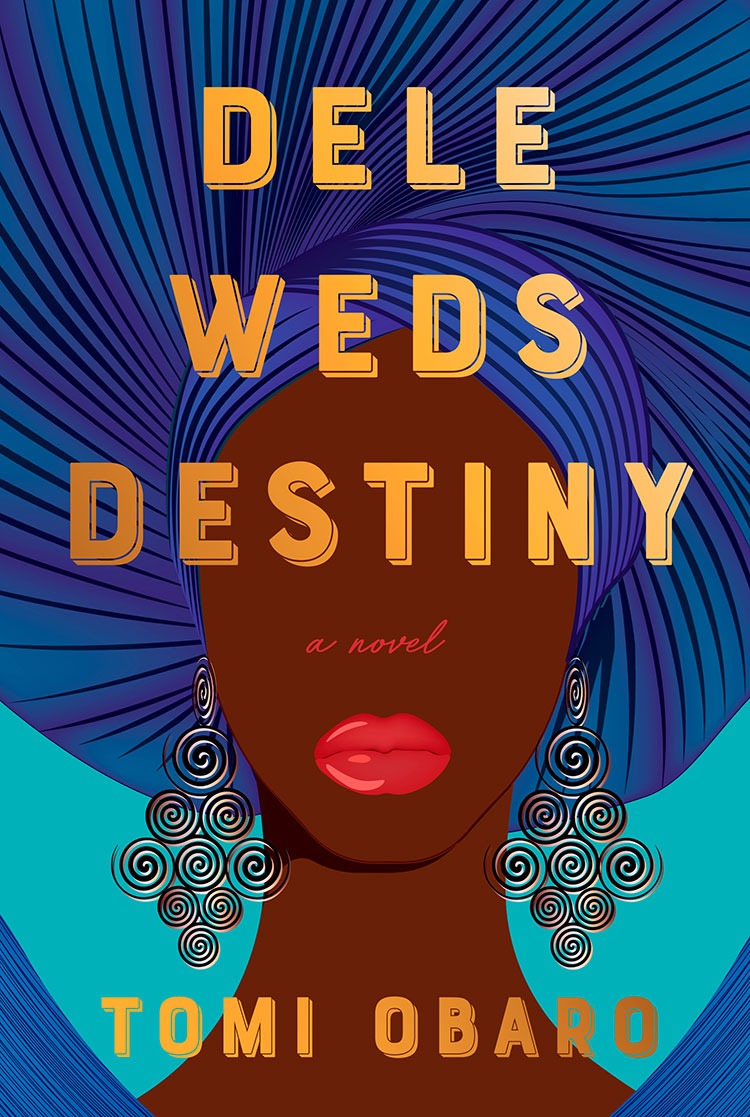

Currently living in Brooklyn and working as the deputy culture editor at BuzzFeed News, Tomi Obaro has Windy City ties. A University of Chicago alum, she was also an assistant editor at Chicago magazine for about three years. In her debut novel, Dele Weds Destiny, out this June with Knopf, the Nigerian-American author tells the interlocking stories of Enitan, Zainab, and Funmi, unlikely friends who bonded while attending university in Zaria.

Thirty years after that period of indivisible intimacy — decades during which they’ve led decidedly different lives — the three women rendezvous in Lagos for Funmi’s daughter Destiny’s wedding. As they travel to and prepare for the lavish celebration, they reflect on their shared and separate histories and dreams, betrayals and loyalties. By the time of the novel’s surprising climax, Obaro has delivered an intense and incident-packed exploration of friendship, culture, class, and love.

How did you decide to tell the story using a rotating point of view, letting the reader see events through each of “the trio’s” eyes? What does it let you do that a single perspective wouldn’t?

It was mostly an organic decision for me; I knew that I wanted to write from the perspectives of Enitan, Funmi, and Zainab as soon as I thought of the characters. And writing from multiple perspectives is inherently more interesting to me as well; there’s more room for my imagination when I don’t feel restricted to one character.

You open the book with food imagery — “they are eating something out of frame, pounded yam, perhaps, or maybe eba” — and cuisine features prominently throughout. I like how this both situates the reader within Nigerian culture, and how it makes me imagine book clubs serving some of the dishes at their meetings. When book clubs discuss this story, what do you most hope they talk about and why?

I don’t have any set expectations; I just hope it provokes a lot of conversation!

You say early on that the women are “essentially sisters” and that seems to be one of the most crucial motifs. Why focus so vividly on friendship and this notion of metaphorical sisterhood?

I’ve always been drawn to novels about long-lasting friendships and how they change over time. And I was inspired by the relationship my mom has with her two best friends as well. I also thought it would be fun to structure the book around a wedding but to have the heart of the novel really focus on friendships — as opposed to romantic love, which attracts a disproportionate amount of attention.

The various mother-daughter relationships among these women are often fraught, and you show how sometimes young women are better able to get support and guidance from older women who are not necessarily blood relatives. How did you manage to write so convincingly about both youth and middle age, and about these intergenerational dynamics?

Thanks for thinking I pulled it off! I really tried to write from a place of empathy for each character, even if the portrayals could seem a little unflattering.

What other novels or novelists did you draw inspiration from as you were writing?

I sought out domestic fiction by African women writers. I read Buchi Emecheta’s semi-autobiographical novel Second Class Citizen and Mariama Ba’s So Long A Letter, for example. Both of those books are brutally honest about the reality of being a woman in the time periods they’re set and both authors wrote later in life, which I found personally inspiring.

How long did it take you to write this novel, and how did you balance your obligations as an editor with your own creative project?

I started writing it in the summer of 2019 and finished in the spring of 2020. Early on, I was very motivated and just wrote whenever and wherever I could; on my phone on the train, after work and before work. Then after that first initial rush of adrenaline, I had to force myself to be more disciplined about it. But because editing is not writing, it felt fairly easy to juggle both. I didn’t feel like I was using the same part of my brain when I would write in the mornings.

You depict Lagos with loving yet critical warts-and-all detail, painting a picture of the city as a physical space, but also as an emblem of energy and vitality, class inequality and resentment, beauty and abjection. Was the city always so prominent in the book to the point where it’s almost as important and lifelike as the characters?

Yes, I knew that Lagos would have a place in the book. It’s such a chaotic place and it felt natural for me to situate parts of the book there.

What’s next, if you can say?

I’m working on a novel that’s primarily set in Chicago, actually!