The year: 2000.

The place: Borders, at the corner of Clark and Diversey.

The time: Thursday evening.

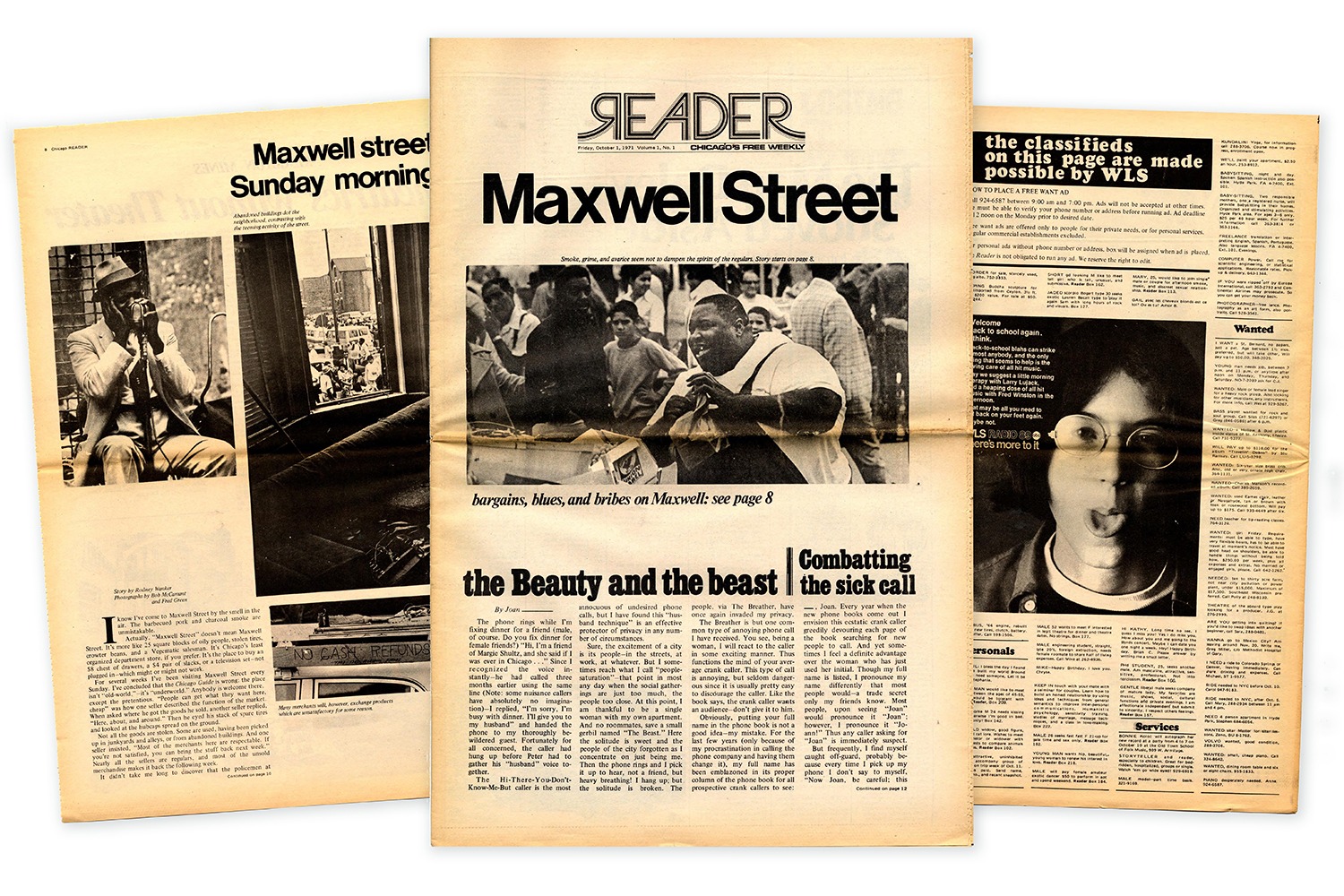

The scene: A Chicago Reader truck pulls up to the curb. The driver unloads hundreds of fat, four-section broadsheets, building a miniature battlement of newsprint in the lobby. By Saturday morning, they’ve all been snapped up, tucked under the arm of every ‘L’ rider on the way home from an office job in the Loop, and into the backpack of every thrift-store dude on a one-speed bike.

At the turn of the century (we can now use that phrase to refer to 2000), the Reader was the newspaper of record for Chicago’s underground scene: the source for music listings, apartment classifieds, and personal ads. Starting on the cover, and winding through the ads, was a long, reported-to-the-pencil-nub tale about a Patti LaBelle superfan or corruption in the Tollway Authority. It was so hip that the movie High Fidelity featured a Reader music critic named Caroline Fortis.

“You’re Caroline Fortis?” John Cusack says, incredulously, when she walks into his Wicker Park record shop. “I read your column. It’s great. You really know what you’re talking about.” He’s so smitten, he makes her a mix tape.

The Chicago Reader turns 50 this week, an age I never thought it would achieve. I feel the same way about that birthday as I did when the Rolling Stones turned 50: You ain’t what you used to be, but when you were what you used to be, you were the best.

The Reader was launched in 1971. At the time, the paper’s lakefront stronghold was populated by a mix of gays, artists, musicians, actors, and young professionals skeptical of the first Mayor Daley’s political machine. The so-called Lakefront Independents were key swing voters during Harold Washington’s 1983 campaign to become Chicago’s first Black mayor. Right before the election, the Reader published an article aimed at reassuring white voters about Washington’s credentials. Widely copied and stuffed under apartment doors, it helped him squeak to victory. Throughout the Council Wars between white aldermen and Washington’s minority allies, the Reader remained in the mayor’s corner. Its star reporter, Gary Rivlin, went on to write Fire on the Prairie, the definitive book on that divisive era in Chicago. John Conroy’s decades-long investigations of police torture helped lead to the conviction and imprisonment of Detective Jon Burge.

In its heyday, the Reader was the finest publication I’ve ever read, or written for. I first picked up a copy in 1993, when I was a newspaper reporter in Downstate Illinois. On the cover was Lee Sandlin’s “The American Scheme,” a 20,000-word essay on how the post-war quest for success consumed and killed his father. As soon as I finished Sandlin’s story, I decided I was going to move to Chicago and write for the Reader, which seemed like a place where a journalist could write about any subject, at any length, in any style.

Four years later, I broke in with a long narrative about learning to play the horses from a professional tout at Sportsman’s Park. Eventually I worked my way up to staff writer, turning out only-in-the-Reader pieces on a teenaged Frank Sinatra impersonator, a man who sold socks by the freeway, and the “callers” who drummed up business outside hip-hop boutiques in Roseland. I was also sent to the South Side to check out a state senator with a funny name who was running for Congress against Bobby Rush. That cover story became the basis of a book, Young Mr. Obama: Chicago and the Making of a Black President.

By the time I left in 2005, the Reader’s heyday was over. The paper wasn’t thriving in the internet era. Craigslist poached its lucrative classified ads, taking over the Reader’s role as the place to find a job, a date, or an apartment. The advent of blogs was changing the definition of “alternative journalism.” When the Reader was founded, it was the alternative to the Sun-Times, the Tribune and the Daily News. Now, it was one of dozens of voices, competing with the likes of Pitchfork as the city’s definitive outlet for music criticism.

When a potential new audience was moving onto the internet, the Reader declined to post its stories there. In 2004, the Reader came out with a new design that finally brought color to the front page. The Trib’s media critic snarked that it brought the paper “into the late 1990s.” On the day the new cover debuted, I handed out copies at the Fullerton ‘L’ stop. Gray-haired men and women rushed to grab copies. No one under 30 was interested.

In 2000, the average 28-year-old Chicagoan would tell you: “The Reader is my Bible!”

In 2010: “I haven’t read the Reader in awhile.”

In 2020: “I’ve never heard of the Reader.”

The Reader’s hippie founders sold out to an alternative newspaper chain called Creative Loafing, which fired four staff writers who specialized in long-form journalism. The model of turning a reporter loose to spend months investigating a story — the heart and soul of the classic Reader — had become “economically unsustainable.” In the years to follow, the Reader was passed around to the Sun-Times, then to a consortium headed by former Ald. Edwin Eisendrath, a group led by the publisher of the Chicago Crusader, before finally establishing itself as a non-profit 501(c)3 known as the Reader Institute for Community Journalism.

Despite the Reader’s 21st Century struggles, it has outlasted many of its alt weekly peers: Boston Phoenix, Village Voice, Minneapolis City Pages. Although its corpus has been reduced from a fat broadsheet to a slim tabloid, the Reader continues to occupy its own indispensable niche in Chicago journalism. Last year, it published a lengthy article by Maya Dukmasova about ex-cops evicting a problem tenant in Rogers Park. Part investigative journalism, part personal essay, it was the kind of story that could only appear in the Reader, the kind of story that would make a young reporter think, “Wow, you can do that in print? I want to do that, too.”