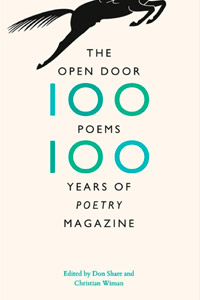

In October 1912, Harriet Monroe, a 51-year-old Chicagoan, published the first issue of Poetry: A Magazine of Verse. In October 2012, that audacious journal still thrives, and to commemorate its centennial, Christian Wiman and Don Share, its editor and senior editor, have assembled an anthology of its verse and prose: The Open Door: One Hundred Poems, One Hundred Years of Poetry Magazine. (The book takes its title from Monroe’s 1912 manifesto, which kicks off the collection: “The Open Door will be the policy of this magazine—may the great poet we are looking for never find it shut, or half-shut, against his ample genius!”) Wiman and Share will host a Poetry centennial celebration and release party for The Open Door at this Thursday at the Poetry Foundation. Share recently discussed how the collection was assembled, who made the cut—and who didn’t—and the lingering presence of Harriet Monroe, the magazine’s founder.

In October 1912, Harriet Monroe, a 51-year-old Chicagoan, published the first issue of Poetry: A Magazine of Verse. In October 2012, that audacious journal still thrives, and to commemorate its centennial, Christian Wiman and Don Share, its editor and senior editor, have assembled an anthology of its verse and prose: The Open Door: One Hundred Poems, One Hundred Years of Poetry Magazine. (The book takes its title from Monroe’s 1912 manifesto, which kicks off the collection: “The Open Door will be the policy of this magazine—may the great poet we are looking for never find it shut, or half-shut, against his ample genius!”) Wiman and Share will host a Poetry centennial celebration and release party for The Open Door at this Thursday at the Poetry Foundation. Share recently discussed how the collection was assembled, who made the cut—and who didn’t—and the lingering presence of Harriet Monroe, the magazine’s founder.

Tell me a little about the process of assembling this collection. Did you sit down and read every issue of Poetry?

We did, but we didn’t have years on end to do this. So Chris and I split the history up. We each got about half of it. We already had a sense of the poems that we wanted. We knew the greatest hits. What we wanted to find were poems that would surprise people, things that were not usually available or found in a book. But we really read poem after poem during all our waking hours for months beginning last spring [2011]. We were in our old office at 444 North Michigan Avenue office, and we were able to rent a conference room kind of in the bowels of the building. We printed out heaps of poems and read them and scribbled on them and went back and forth and back and forth. In the end, we had a huge conference room with tables everywhere and sheets of these poems laid out all over the place. And we just wandered around looking at them.

How did you and Christian decide which poems to include? Any heated discussions?

There weren’t heated discussions. One of the great things about this process was that it was a magnified version or a pressurized version of what we do together every month at the magazine. Chris and I are very different people. Our tastes are different, our enthusiasms are different, the things we don’t care for are different. We complement each other. But the great thing about it is that it’s always in the form of a conversation. We don’t have shouting matches or disagreements; it’s more like a push and pull.

Were there certain things, like T.S. Eliot’s “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock,” that just had to be in there?

It’s like being a kitchen. You have a sense that certain things have to be in there, but if you just do things by the book, then the end result is missing something. It’s not flavorful. In a way, to surprise ourselves, and so our readers would be surprised and interested, we had to dispense with some things. And then there were poems that might just have vanished if we hadn’t put them in the book.

Like what?

One of those that surprised us was the Tom Disch poem “The Prisoners of War.” Disch is known as a science-fiction writer, but he’s also a great poet. In September 1972, Poetry had a famous anti-war issue with a gray cover. Disch’s poem uses words we find in our vocabulary today: civilization, justice, terror. So there were poems like that that seemed to foretell their eventual significance. Here’s one that survives because our vocabulary has caught up with it. It’s a troubling poem:

. . . at moments that may still suggest such concepts

as “Civilization” or “Justice” or “Terror,”

and at ourselves, those still alive, who stand

before what might have been, a year ago, a door.

That’s a picture right out of the headlines today.

You didn't include some notable poets, like Carl Sandburg and Vachel Lindsay. Why leave them out?

Those poems and poets are so well known to us. We wanted to avoid the obvious. We’re not passing over them. It felt like, if we put them in, it was because we were obliged to. When you look at the poems now, because we’ve been taught them and we know them, you sort of pass them over. We didn’t want to have poems that seem that way.

How did you settle on the particular arrangement?

We made it a sequence. What we wanted to do was for the poems and also the prose quotes that break them up to resonate with each other. They don’t have to be right next to each other. The prose quotes might illuminate not just the poems nearby, but also something that came before or is coming after. It’s almost like the book is just one big poem.

The collection is bookended by Ezra Pound and William Butler Yeats. Did that seem like a natural decision?

It did. I think each of us had ways of imaging the book. For me, starting with that Pound poem, “In a Station of the Metro,” seemed really important. I thought, Here it is 1913, and this poem that’s emblematic of the way modern poetry unfolded. At the time that was quite a shocking apparition. To my mind, kicking the book off with that poem was totally a given. Yeats’s “The Fisherman” [the volumes concluding poem] sort of bookends everything nicely. Yeats was a mentor to Pound, and Pound learned a lot from Yeats and worked as his secretary. So having those two great poets bookend the collection seemed easy for us, but also it pays tribute to what they did for the magazine for many years.

Great poets may bookend it, but Open Door features some younger poets as well, such as Indiana’s Brooklyn Copeland, born in 1984. Why was that important?

We’re in the process of discovery. That’s what Harriet did, and that’s what all the other editors do. We wanted to reference that as well. I said to Chris, “A lot of these younger poets, years from now, I wonder how they’re going to hold up?” He had a great answer: Part of our responsibility was to stand by these younger poets.

You mentioned Eliot talking about the shadows of past poets overlooking your shoulder. Was Harriet looking over your shoulder as you assembled this?

I really do think so. She was quite a visionary. She looked at Chicago and saw an art museum and the opera, but where was the place for poems? She created this sense that poetry needed a place. I think she would be extremely pleased to think that the magazine was around after 100 years. Its whole history was characterized by near misses with going under. It’s a constant story of barely surviving, yet it never missed an issue ever. She would be gratified that what she came up with continues.