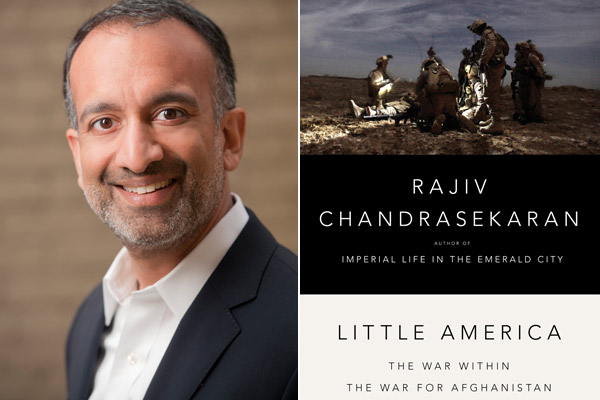

Few American journalists know the Middle East better than Rajiv Chandrasekaran. A longtime reporter and editor at The Washington Post, he spent years as the paper’s bureau chief in Baghdad; his book about Iraq, Imperial Life in the Emerald City, was chosen by The New York Times as one of the 10 best books of 2007. His new book, Little America: The War Within the War for Afghanistan, gives an insider look on the war on terror. He’ll appear this Sunday, Oct. 21, at 2 pm at the Chicago Humanities Festival—but agreed to give Chicago magazine a sneak preview.

What will you be talking about here in Chicago on Sunday?

I’m going to cast the net more broadly than just the war, beginning with the earliest days of the U.S. engagement with Afghanistan. The first wave of Americans arrived there in the late 1940s as part of an ambitious effort to develop the southern part of the country. There’s a much larger story to tell. Unfortunately, we are repeating the same mistakes today.

You’ve made more than a dozen trips to southern Afghanistan since 2009, right?

That’s right. I’ve probably spent about eight months total on the ground there. My last trip was last summer.

How have conditions changed over that time?

In parts of the country, the security situation has improved. That shouldn’t be a surprise: when you send U.S. troops in, they do good things. They did beat back the Taliban in places. But the big question is whether any of this is sustainable.

Your new book is about the “war within the war” for Afghanistan. What does that mean?

What I discovered was that there were multiple wars. It’s not just our troops fighting the Taliban. There have been wars between American commanders; between American diplomats and the coalition military headquarters; between Americans and our NATO allies. And in Washington, fights inside the bureaucracy, including between the State Department and the White House. Our war effort has been beset by numerous conflicts.

You make the case that the United States has never understood Afghanistan and probably never will. Why?

Because we fail to take the time to understand the history, the culture, the traditions, the religion of the country. Too often, we think that we can come in with what seems to be, back in Washington, a smart, workable solution. But those approaches work only if you have a genuine consultation with the Afghan people.

Do you think the war in Afghanistan is failing?

The good war has turned bad, in part because of mistakes we’ve made, in part because of the malfeasance of the Pakistani government, and in part because the Afghan government has not been a partner with us. The surge did not make sense. But nor does packing up and going home right away. If we were to leave tomorrow, it likely would result in the Taliban expanding control over much of the country, plunging it into another civil war. We promised the Afghan people a better future. We have a moral obligation to help them. That doesn’t mean staying there in perpetuity. We need to move quickly to build and train the Afghan army and police, so they can take over the fight from us.

What are the main differences you’ve seen between how the Bush and Obama administrations have approached the war on terror?

A better question might be: What are the differences in how they have approached the task of rebuilding shattered societies? In Iraq, the Bush administration had inexperienced twentysomething neocons trying to do it. In Afghanistan, the Obama administration turned to the State Department and other parts our federal bureaucracy, but they, too, screwed things up. Both approaches have been dysfunctional. The real question is: Should the United States be in the business of nation building?

What have you learned about the situation in Afghanistan that the average American doesn’t grasp?

That this war is not going away anytime soon. The hope that we can wipe our hands clean of Afghanistan is totally misguided. Afghanistan needs a modest, sustained American commitment. That does not mean thousands and thousands of American troops. It means some troops, to help the Afghan security forces and to go after any big-fish terrorists that are discovered there.

Afghanistan may be the most dangerous place on earth right now. What’s it like going there regularly?

Each trip has been harrowing it its own way. Afghanistan is not an easy place to get to. I’ve been in helicopters that have taken fire. I’ve walked around with foot patrols where there are explosive devices. But you can’t understand what’s really going on if you’re not there on the ground, talking to people, having tea with Afghan elders. You have to see it with your own eyes. These are risks worth taking. I just didn’t tell my wife what I really encountered.

Photo credit: Bill O'Leary