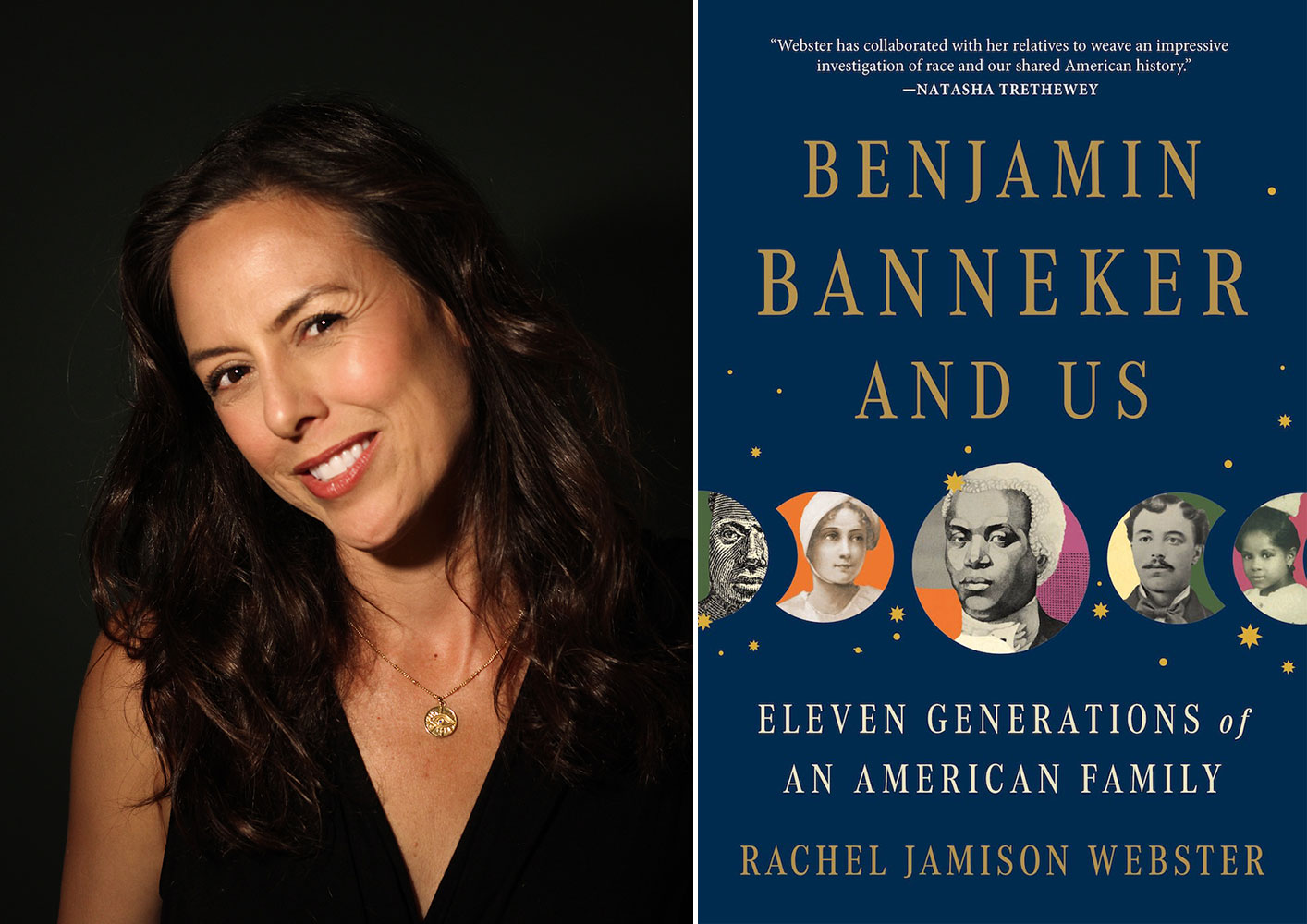

Genealogy has long been a popular American pastime, perhaps because we understand that where our predecessors began impacts where we stand today. Following the story of an ancestor helps us grasp the grander scheme of things — a particular forebear can be a revelatory grain of sand in the ever-shifting dunes of history. In her latest book, Benjamin Banneker and Us: Eleven Generations of an American Family, Rachel Jamison Webster examines the stories of her various ancestors, most notably Banneker himself: a free person of color living in the Revolutionary era who published the first almanacs by a Black man in the new U.S., helped to survey Washington, D.C., and corresponded with Thomas Jefferson, (“calling out Jefferson on his hypocrisy as an enslaver who wrote about freedom”).

The author of four books of poetry and a professor of Creative Writing at Northwestern University, Webster teaches a class there called “The Situation of Writing on Literary Ethics,” fostering nuanced conversations about identity and representation, while honoring the imagination as its own radical and spacious intelligence. Here, she acknowledges that “my branch of the family ‘passed’ as white several generations ago, losing track of these figures and failing our responsibility to our Black brethren” and questions “my own position as a white woman and studying the origins and ramifications of whiteness itself.”

Out this month from Henry Holt and Co., her deeply researched and vividly imagined book feels both very much of this moment and for the ages.

How much time elapsed between when you made the discovery that Banneker was one of your ancestors and when you said, “I have to write about this?”

I learned about this ancestry during the stressful election season of 2016 when I was thinking about history — and America — in a new way. As soon as I learned about these ancestors, I wanted to write about them. But as a white person, I grappled with the ethics of writing about an ancestor who was a prominent Black figure. In 2018, I wrote and published an essay called “White Lies and Fiction,” and then I did two more years of research, freewriting, and soul-searching. In 2020, my cousin Edie got in touch with me, and when we began talking, I knew that this would be the right form for the book — a conversation between me and my Black cousins, and between the past and the present.

The book’s structure blends past and present, using literary techniques to embody in an almost novelistic way the life of Banneker and others. Why did you settle on this mode of storytelling?

I was interested in putting the past into conversation with the present, as a way of tracing historical underpinnings and asking what these stories can teach us now. It is very rare to have this much documentation — going back to the 1600s — for a family of color, and I realized I needed to honor these ancestors by compiling the documentation about their real lives.

At the same time, I kept imagining them as full, complex people — more than names and dates. The hybrid storytelling form that I landed on resembles oral history. In oral histories, families rigorously preserve names, dates, and lineages, but they also fill in those facts with feelings, scenes, and details.

Your byline says your name, of course, but also “with Edith Lee Harris, Robert Lett, Gwen Marable, and Edwin Lee.” Can you tell us why that is?

My conversations with my cousins became central to the book. They shared 40 years of their research with me and told stories from our lineage and their own lives. Giving them a byline was my way of honoring their authorship in the project. It was a way of acknowledging oral history as a legitimate form of knowledge. It was also a way of complicating the idea of the individual author. This book owes its existence to generations of ancestors, and generations of griots who held and shared our family stories.

As we’re speaking, Florida is once again in the news over its Department of Education’s rejecting an AP class on African American studies. Why do you think these attempts to limit the discussion of history, race, and privilege keep cropping up? How do you think they might impact your book?

There are a couple of ways to answer this question. The first is in terms of power. Any time a structure relies on denial — on keeping people away from information — it is meant to distract people from ways that leaders and institutions are not acting in their best interest. This move by Governor DeSantis is a political stunt and a dangerous act of censorship that has precedents in history. For instance, my book tells the story of the legal invention of “whiteness” in the Chesapeake in the 1690s, which was the landowners’ way of separating the working class from one another along lines of race. This allowed the wealthy to economically subjugate their white workers, while increasing investments in the slave trade.

Another way of answering this question is psychological. As a culture, we have not done a good job of modeling the process of learning. Learning is a humbling process that relies on self-examination and analysis of structures, on facing errors and blindspots and then transcending them. People seem to associate the process of learning with an experience of being shamed. These AP courses are not designed to punish white people but to elucidate a rich and robust history. It is not an opinion but a fact that the U.S. economy was built on the enslavement of Africans, and that African American ingenuity and resilience have shaped American history. Benjamin Banneker and his family fought for civil rights in the early days of the nation, and I’d be honored if my book became part of the conversation now.

One of the things I admire is how you dramatize the thrill of doing research. Do you have any tips for readers who are researching their own family histories, either on how to do that or how to eventually document and share the stories they find?

First, be open to collaboration. Reach out and compare notes with your DNA cousins. You may not always agree, but together you will find more documentation than you could alone. Second, do contextual research as well as genealogical research. I saw documents — court records, tax records, etc. — that I didn’t know how to interpret until I had researched the laws and contexts of the time. Reading historical texts, novels, and even watching movies set in the time of your ancestors, can help you to understand their lives.

You talk about your daughter a lot in this book. What do you hope that her generation might understand about history and solidarity that prior generations maybe have not?

I hope that the next generations will not see this as an either-or situation. Some of the white fear around learning African American history is that if they acknowledge these histories, they will lose their own. We have always had a diverse country, and that diversity has been the source of strength.

We have also always failed to dispense justice equally across lines of race, economics, and gender. I hope that young people will see these failures, but also acknowledge successes. And I hope they will value democracy enough to participate in it and demand that our society and laws keep expanding to serve all people. I do see this next generation as kind, and naturally inclined toward inclusivity and allyship. They are helping us to evolve.