Jim Masino had been out of town for some time when he walked into Beacon Tap in Des Plaines on a balmy Saturday night this past September. The informal 25th reunion of Maine West High School’s Class of 1981 was already under way and 150 people had shown up. About half had RSVP’d, but Masino had been listed as a “lost student” in the alumni database, and his arrival took the reunion coordinator, Rich Russo, by surprise.

At 43, Masino hadn’t changed much from how he looked in high school-he had a full head of tousled hair, albeit somewhat gray, and he wore blue jeans and a green polo shirt. As the people around him exchanged bear hugs, he quietly moved through the crowd. A half smile stayed on his face most of the night. “He kind of seemed more distant than others,” Russo recalls. “He didn’t seem like he had a lot of friends to go to, nor they to him.”

After a while, Masino took a seat near a group of women. As beer bottles clinked and cameras flashed, he drew one of them into a conversation about another Maine West alum, a former friend of Masino’s named James McNally. Masino seemed to think that McNally was a bad guy who had killed some of Masino’s friends. Masino told the woman that she could be in danger. He told her he had a gun, and she should get one for protection from McNally. To the woman, who hadn’t seen Masino since high school, he seemed (as she put it in an interview) “deranged.”

Five days later, as James McNally, a married father of three, left his home in the northwest suburb of Bartlett in his silver BMW, a maroon van cut him off. From five feet away, the police say, the van’s driver pointed an assault rifle at McNally and emptied the chamber, the bullets penetrating his upper body. Police say the shooter was Jim Masino, who now faces charges on eight counts of murder-each of the charges related to this single incident. Masino has pleaded not guilty.

If the police account holds up, the sad case of the murder of James McNally tells the story of a friendship that deteriorated with fatal consequences, apparently as Masino’s mental health declined. But it also raises the grimly persistent question of whether more can be done to keep guns out of the hands of mentally unstable people. Over the years, Masino had had assorted run-ins with the authorities, including a 1988 felony conviction for unlawful restraint involving his then girlfriend. Ordinarily, convicted felons aren’t allowed to have firearms, but in 2002, then governor George Ryan pardoned Masino, essentially restoring his access to guns. As it turned out, Masino had amassed enough firepower that he rented a storage unit to hold all of it.

The case has an unhappy irony, too. In seeking his pardon, Masino sought affidavits from his friends, attesting to his character. One of the endorsements came from his old pal James McNally.

—

|

The two men had known each other for years, since Masino was about seven and McNally eight. Their families had both moved to Des Plaines in the late 1960s, and McNally, the youngest of four children, and Masino, who has an older brother, grew up two blocks from each other, on the tidy streets of one- and two-story brick frame houses tucked just off bustling Rand Road.

In this tight-knit neighborhood, the spirited, generous McNally was the nucleus of a group of boys who went to grade school, took their first communion, and went to Maine West together. They comforted each other when John Wayne Gacy murdered one of their schoolmates and rejoiced when another student’s father, a Des Plaines Police detective, helped capture the notorious serial killer. In later years they went to each other’s weddings, and many of them are still close today.

Over the years, however, Masino endured some tough knocks. His parents had divorced, remarried one another, and then divorced again while he was in high school, with his mother and father both accusing the other of abuse. Masino worked at a Venture store and as a mechanic while still a teenager, learning the fundamentals of a trade that would eventually allow him to move out on his own.

While still part of the same core group of friends, McNally and Masino headed in different directions as they got older. McNally graduated from Maine West in 1980 and worked as a laborer-often with his father, who was in the construction business. In 1984, while working in Elk Grove Village on one of his father’s projects, McNally met Barbara Larson, and soon after, the two started dating. They were opposites in personality-she more serious and organized; he, outgoing and sentimental. “He was Mr. Christmas,” Barbara recalls, and indeed, he asked her to marry him two days before that holiday in 1988. At the time, she had a bad cold and was wearing pink sweatpants and no makeup. “If you love me like this, you can have me,” she replied, happy that he had finally proposed. They married in September 1990.

As for Masino, the path he had followed sometimes landed him in trouble with the police. In the summer of 1981, the year he graduated from high school, he was arrested on misdemeanor charges of disorderly conduct, criminal damage to property, trespassing, and unlawful use of weapons. He had been carrying a can of Mace, a three-inch knife, and a homemade iron mallet, according to police reports, which also indicate that Masino received supervision for the weapons charge.

Shortly after, he allegedly got into a fight with a former classmate that landed both of the young men in the hospital. In this instance, Masino could have faced felony assault charges and a jail term. However, news reports from that time indicate prosecutors told the families to settle their ongoing conflicts-which included slashed tires, broken windows, and other vandalism-out of court.

In the years that followed, Masino took courses at a motorcycle institute and a mechanic’s job at a Yamaha franchise. In 1986 he bought a one-bedroom condo in Arlington Heights and soon was sharing the space with his then girlfriend. By late the next year, their relationship had ended badly. Court records show that in November 1987 Masino locked her in his car and slapped her hard enough to bruise her as they drove to lunch. The girlfriend moved out of his condo and filed charges of battery and unlawful restraint. Masino caught a break when he was allowed to plead guilty to the felony restraint charge and avoid jail. The court ordered him to serve 30 months’ probation, to stay away from the woman, and to “continue counseling as recommended by Northwest Mental Health Center,” according to case records.

“I did not wish to see [the girlfriend] again, did not mind paying the $70 fine, and was not concerned about the probation because I am not a troublemaker,” Masino said in papers filed 12 years later, as he tried to get his rights to own a firearm restored in a petition for executive clemency. “I never misused firearms and never will.” The petition states Masino missed hunting with his father on land owned by the family near Lake Geneva, Wisconsin. It also says the felony conviction had hampered Masino’s efforts to advance his career in insurance.

—

Governor George Ryan’s commutation of the sentences for all Illinois prisoners on death row was still several years away when Masino began his bid for clemency. James Valentino Jr., who was then president of the Illinois State Rifle Association and arguing headline-making court cases on behalf of gun shop owners, represented Masino through the steps.

Obtaining a pardon-one of the more sweeping exercises of executive clemency-is difficult; in the main, it is designed to be a last-resort check against judicial error. Still, hundreds of people apply for a pardon each year because it can essentially erase a conviction from the books, reinstating rights and privileges that typically elude those with a felony record. Anyone convicted of any crime is eligible for a pardon, although people with lesser charges stand a better chance of succeeding. Statistics from the Illinois Prisoner Review Board for eight of the past nine years show an annual average of 544 pardon requests received, with usually fewer than 25 of them granted. In 2002, Ryan’s last year in office, he granted 233 pardons, in addition to the 172 commutations for those on death row.

Valentino, of Algoma, Wisconsin, says he handled quite a few of the petitions each year and took on only those that he thought stood a good chance of success. What most distinguished Masino? “He had some excellent references,” Valentino recalls. One of them came from his longtime friend James McNally. “He really did have a soft spot for people who were less fortunate than him,” says Barbara McNally. “He felt like he was the luckiest guy in the world.”

—

“I have known James [Masino] for 28 years including his family, and I know he has behaved in a moral and law-abiding manner,” read the character affidavit signed by McNally, dated November 2, 1999. Other friends, who, like McNally, had been a year ahead of Masino at Maine West, also submitted affidavits. They described Masino as responsible, a hard worker, punctual at his job. “He has a respectable reputation among his friends.”

Now there are regrets, disgust-a sense that Masino betrayed and fooled them all. One former friend explains that he was only trying to be there for someone who asked for help: “At that time, [Masino] seemed pretty harmless.”

Support for Masino’s cause did not extend to the Office of the Cook County State’s Attorney. Far from a harsh sentence, 30 months’ probation for an unlawful-restraint charge was already “very lenient,” wrote James McKay, chief of the felony trial division. “It would be inappropriate to grant him a pardon in light of the nature of his offense, and the fact that he has never served any time.”

It took more than two years from the filing of the affidavits to the decision, not wholly unusual since most governors deal with petitions for clemency toward the end of a term. The Illinois Prisoner Review Board’s findings had recommended Masino for a pardon. The final outcome lay with George Ryan. He issued it on January 15, 2002, noting, “By Granting Of This Pardon All Rights To Firearms Possessions Are Restored As If No Conviction.”

Not too long after, friends say, Masino seemed to begin drifting away. Most of the friends had married and were raising children, while he stayed single, a bit of an outsider with a tendency toward odd behavior. In late 2004, Masino sold the Arlington Heights condominium he had owned for so long that it still had an unfashionably old avocado green stove. He then moved to Fargo, North Dakota. To people who had known him since grade school, the departure seemed sudden. His lawyer, Marvin Bloom, now says Masino was trying to fight demons few of the friends could have known about. “He thought he could go to Fargo, then Michigan, then Wisconsin-that he could get away from all this.”

When Masino came back in 2006, he still stayed some distance from home, renting a modest apartment on the outskirts of Kenosha, a few blocks from the muffler shop where he had been hired as a technician, starting work August 28th. He gave no particular reason for his return. While some of his conduct had gone from bizarre to hurtful, nobody anticipated that he truly wanted to harm anyone.

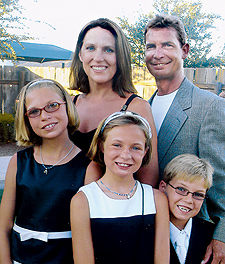

McNally, who was 44, lived with his wife, Barbara, two daughters, and a son on Pond View Lane in Bartlett, in a spacious brick home with a three-car garage. They had moved to a new subdivision in June 2003, after returning from Germany, where Barbara’s job had taken them for a year. McNally had put his career on hold to be a stay-at-home dad. Neighbors were used to seeing him working in the yard or going to and from the children’s activities.

Just before 2 p.m. on September 14, 2006, McNally (according to police accounts) pulled the family’s BMW sedan out of the driveway. He probably didn’t notice Masino waiting in a 1990 Chevy van. As McNally drove west on Pond View, Masino began his approach. McNally had made it about a quarter mile when Masino pulled up and began shooting. Witnesses told police that as McNally’s car lurched forward, into a fence surrounding a construction site, the van fled. Police say Masino used an SKS assault rifle that has an effective range of 400 yards and can penetrate a police vest.

An information technology manager working at a Chicago-based corporation, Barbara McNally was at an off-site meeting when the killing occurred. “The senior IT director walked in,” Barbara remembers, “and he said, ‘There are some people here that need to talk to you.’ They told me my husband had died. They told me he was shot.” A company car drove her home, and she and her children stayed with a friend while police searched their house for potential clues. “It was really hard to think who would do such a brutal thing,” recalls Barbara.

—

By the police account, Masino’s trip back to Wisconsin included several stops. He broke down his rifle and dropped parts into Lake Michigan and other bodies of water; he tossed his clothing into a series of Dumpsters; he cleaned his van at a car wash. Meanwhile, based on a description of the suspect’s vehicle, a bulletin about Masino came through to Kenosha police, who set up surveillance. Around 8:30 that night, officers spotted the van being driven ten blocks from Masino’s apartment. After pulling him over and finding a handgun, they took Masino in on a weapons charge and the van was towed to an evidence bay, says Kenosha lieutenant Ron Bartholomew. But the police didn’t have enough evidence yet to charge Masino with murder; Masino posted bond with a credit card and rode a bike to work the next day.

Detectives from the Major Case Assistance Team in Illinois were in Wisconsin hours later, staking out Masino’s home and work. Around dinnertime, Masino biked back to his apartment. The Illinois officers met him at the door. “He actually invited us into his apartment,” says Arlington Heights police commander Kenneth Galinski. “He tried to play it as smooth as possible.”

Armed with search warrants, police also broke open a storage unit Masino had rented near his home and found it held an assortment of small-caliber handguns and ammunition. The detectives then took Masino back to Bartlett. Once advised of his Miranda rights, says Bartlett sergeant Michael McGuigan, Masino admitted the shooting on videotape. In mid-October, a grand jury indicted Masino on eight counts of murder, and he remains jailed. His mother hired the lawyers Marvin Bloom and Peter Vilkelis to defend her son.

At his November arraignment in Cook County Circuit Court in Rolling Meadows, Masino wore a tan prison jump suit and handcuffs. Before he entered the courtroom, Barbara McNally asked for permission to stand at the prosecution’s podium. The people who came to be with her that day watched as she faced the door Masino would come through. Pinned to the lapel of her black business jacket were buttons with photos of her family. She looked directly at Masino as the bailiffs led him in, but he did not look up to meet her eyes. (The McNally family has filed a wrongful death civil suit against Masino.)

A few minutes later, Vilkelis told Judge Thomas Fecarotta that Masino would plead not guilty. He noted that Masino was “heavily medicated” and when at Cook County Jail was held in Division 8, the unit for detainees requiring a doctor’s care. Masino’s attorneys contended there was a “bona fide doubt” he was fit for trial, and on December 27th, the court agreed. Masino has been committed to the custody of the state Department of Mental Health facility in Elgin, where inmates can undergo treatment to enable them to stand trial. Whether Masino will ever go to trial remains an open question.

In a telephone interview, Bloom said his client was showing signs of paranoid schizophrenia. “He believed McNally was a paid assassin for the CIA,” he said. “It was not a sudden thing-Masino has been tormented over the years.”

—

Perhaps in some way Masino went to his class reunion to try reaching out to old friends before his delusions overtook him. Aside from his surprise appearance there, he had recently touched base, by e-mail, with people he had not seen in nearly two decades. Rick Schulte, a football star at Maine West who went on to play for the Chicago Bears, read an e-mail this past spring from Masino, a guy Schulte remembers best from grade-school birthday parties. Masino had been trawling the Web, and he “saw some site of mine,” says Schulte. “He was complimenting me on my house and everything, saying, ‘Man, you kick butt. Tell me everything, tell me everything.'”

Schulte replied to Masino, half wondering if his old classmate might continue the exchange and bring him up to speed on what he had been doing. But that was it. “He didn’t say anything about himself,” says Schulte.

The day after the Maine West reunion, the woman with whom Masino had talked felt haunted by his behavior. (Because of the traumatic circumstances, she has asked that her name not be used.) She picked up the phone, called the well-known private investigator Ernie Rizzo, and asked for a criminal background check on Masino. A few days later, Rizzo (who has since died) showed her a file containing the records for the 1988 unlawful-restraint charge and the pardon for it from 2002. It didn’t seem like enough to suggest a serious danger. The next day, Masino shot McNally.

Photograph: Courtesy of Barbara McNall

Photograph: Courtesy of Barbara McNall