Eight- to ten-foot waves surged down Lake Michigan, rearing up in inky blue masses, cresting and breaking in the darkness. The wind howled, blowing spray through the air. Three miles east of Monroe Harbor, Paul Redzimski and Mike Agostinelli gripped each other's kayaks in the churning water. The waves battered them, tossing their 18-foot boats like toys. After paddling since dawn from New Buffalo, Michigan, they could see Chicago's twinkling lights, but they couldn't make it to shore. Mike was up to his chest in the 58-degree water, shivering and exhausted, his boat half submerged.

"Paul, it's a wrap. We're calling in."

Mike reached numb fingers into his pocket and clumsily retrieved his marine radio. He set it to 16, the emergency channel.

"U.S. Coast Guard from kayakers. Do you copy? U.S. Coast Guard from kayakers. Do you copy?"

Silence.

—

Less than three weeks earlier, Mike had been on the receiving end of a call. Did he want to paddle across the lake on Columbus Day?

"Yeah, I'm totally up for it," he had replied. Both men had the day off: Mike from his firefighting job in Northbrook, Paul from work as a software developer for JPMorgan Chase in Chicago. Lake Michigan was cooling; the days were shortening. This might be their last opportunity in 2006.

|

A 50-mile, open-water crossing had long been a goal for both men. It's a pursuit with a historical pedigree. Native American paddlers, who plied the Great Lakes in open boats long before Europeans came to this continent, no doubt crossed Lake Michigan, though there's no record of it. In 1679, the Frenchman René-Robert Cavelier, sieur de La Salle, and his men paddled the length of the lake by canoe. Ralph Frese, founder of the Chicagoland Canoe Base, built canoes for a reenactment of that voyage in 1976 and participated in a few 43-mile canoe races from New Buffalo to the 95th Street harbor in the 1960s. Frese, now 80, knows of several other attempts to cross the lake in human-powered vessels in recent years, some successful and some not. "There is always some adventuresome soul who is looking for a challenge," he says. "And Lake Michigan can be a challenge, all right."

Many contemporary efforts include a support boat in case of emergencies, but the occasional intrepid kayaker still tackles the trip solo, like Don Dimond, who successfully crossed all five Great Lakes at their geological midpoints in 1995. There aren't any reliable tallies of the number of attempted crossings and the number of successes, however. "No one knows because so many people do it on their own with no fanfare," Frese says.

Mike Agostinelli, 42, and Paul Redzimski, 45, aimed to join the ranks of those unheralded open-water paddlers. All summer, they thought about it and talked about it. They spent plenty of time on the water practicing their strokes, rescues, and variations on a kayak roll, and teaching classes and leading trips for Northwest Passage, a Wilmette-based outdoor adventure company. Both men were American Canoe Association open-water instructors-a certification requiring rigorous training and examination-and had sailing background and at least eight years of kayaking experience, including plenty on big waves and in rough water. They were strong, fit, and eminently qualified.

But miles from shore, a successful trip is no longer just a matter of skill and endurance. It's a matter of equipment, judgment, and garden-variety good luck. If any of these doesn't hold-a boat leaks, a rescue or repair is botched, the weather turns-what started as an adventure can easily end in disaster.

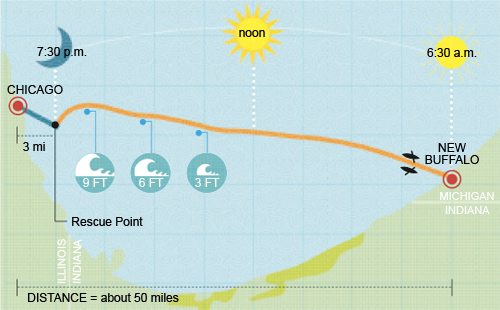

There was no reason to think that would happen this past October 9th, however. The weather was mild; the winds were calm; the two men were well equipped and up for the challenge.

—

The alarm clock rang at 4 a.m. in the Agostinellis' Stevensville A-frame, the couple's vacation home. Carmen, Mike's wife, made poached eggs and toast as Mike and Paul dressed. By 4:30, they were in the Agostinellis' minivan, driving to their starting point at New Buffalo. It was still dark when they pulled into the parking lot, lifted the kayaks down from the roof, hauled their gear out of the van, and started packing their boats.

Kayaks were invented thousands of years ago by the Inuit, who stretched sealskins over wood or bone frames to create boats used primarily for hunting and fishing. The vessels have evolved in recent decades into higher-tech craft made of space-age materials, with sealed front and back hatches for stowing gear, but the boats still retain the features that made them ideal to the Inuit: they are lightweight, quiet, and watertight, and allow a skillful paddler to negotiate rough seas.

Paul was paddling a fiberglass P&H Quest, a solid British kayak with a skeg, a small, retractable fin to help the boat stay on course in windy conditions. Mike had borrowed a carbon fiber Epic Endurance from a friend because the boat had a rudder-a more powerful means of keeping a boat on track. He had owned an identical boat years earlier and considered it the best choice for this trip.

Serious sea kayakers don't know what it means to travel light. In addition to their boats, paddles, life vests, and spare clothing, the men took enough gear to stock a small navy: tow belts, marine radios, an emergency beacon, two cell phones, pocket knives, compasses, three GPS devices, signaling mirrors, lights, first aid kits, boat repair kits, food, water, float bags, extra cockpit covers, sea anchors, whistles, flares, a water filter, bilge pumps, and sponges. It took time to squirrel all this gear away in the watertight front and rear hatches of the boats. They missed their intended put-in time of 5 a.m., pushing back the endpoint of what was already a daylong paddle by at least a good hour and a half.

The sky was growing light by the time Carmen took a photo of the two men just offshore. In it, Mike grins with eager anticipation. A muscular, energetic man of massive enthusiasm and energy, he brings to paddling the same drive and competitive urge that has fueled his 20-year career as a firefighter. Paul smiles calmly, inscrutably. He's unflappable, a man of quiet accomplishment and confidence. If he was eager to get going, you'd never know it.

Then they took off, headed for Montrose Beach. "It was good to be on the water after talking about it and thinking about it and planning it," Paul recalls. "I was looking out at the vastness of the water and was amazed that we were going to paddle somewhere we couldn't see."

The moon was setting ahead of them. A sailboat glided past, heading north along the shore. Then they were alone, two small boats on the vast open water. The wind was calm and the lake nearly flat; Mike set a pace of about five miles an hour and the two just paddled, listening to the rhythm of their blades slicing in and out of the water.

|

After about two hours, the tips of some of Chicago's skyscrapers floated ethereally above the water in the distance. The men paddled mostly in silence, enjoying the space and solitude of a large body of water.

They had no illusions, however. They had watched the weather during the week before their trip. One day the forecast for October 9th called for waves of three to five feet, the next day four to six feet, then three to five again. At one point, the forecast shot up to six to eight. "When I heard six to eight, I thought, It's going to be too rough; we shouldn't do it," Paul recalls. But then it diminished again and so did his concerns. On the day of the trip, they expected the wind to shift and the waves to build, but not beyond what they felt comfortable handling.

To understand wind is to understand the changing moods of Lake Michigan. When the wind is light and out of the west, Lake Michigan paws her beaches with gentle waves. But when strong winds plow down from the north, she's a raging monster. Waves build, growing taller in proportion to the wind speed and distance. On Chicago's shoreline in the southwest corner of the lake, that can mean towering peaks of ten feet and above. (One day this past November, the forecast was for north gales to 40 knots and waves building to 14 to 18 feet. Local sea kayakers buzzed with plans to venture out or marvel from the shore.)

Still, as Mike and Paul approached the middle of the lake, the wind was no more than ten knots and the waves were perhaps one foot with a few whitecaps dotting the blue expanse. Twenty-five miles had gone by pleasantly and uneventfully. Reaching the midpoint called for a celebration. "When we get to the middle, we're going to have to roll," Mike said.

—

Kayakers learn to roll for many reasons. The main one, of course, is to come back up if they accidentally capsize. The spray skirt attached to the cockpit's raised rim, called the coaming, pretty much keeps all water out of the boat. There are other reasons to roll, too: to avoid damage in a collision with another kayak, to protect your body from the impact of a breaking wave, to cool off on a hot day-and, of course, because you can.

Both men had spent years learning a variety of rolls: right side, left side, with a paddle and without. They had practiced rolling boats full of gear, boats full of water, and boats with people hanging on the ends.

It was just about noon when Paul checked his GPS. They had reached the midpoint of their trip. They could no longer see Chicago; clouds had obliterated the skyscrapers. Michigan was invisible because of the curvature of the earth. At the height of a kayaker sitting in a boat-about 30 inches above the water-it's impossible to see anything at surface level more than about a mile and a half away. For an object 25 miles away to be visible, it must be more than 550 feet tall. From where they sat, Paul and Mike could see nothing but water.

Mike flipped over. He gracefully swept the paddle out, snapped his hips, and came back up. Paul did the same, but when he came up he felt water coursing down his right leg to his foot. He checked the zippers on his dry suit. These garments are designed to be completely watertight, with latex gaskets at the neck and wrists, waterproof zippers across the chest and in front of the pelvis, and sewn-on boots. They aren't supposed to leak. Paul's inexplicably had, adding an element of discomfort and raising the risk of hypothermia.

A more pressing matter, however, was the ache in his shoulder. Paul had been using a large "wing paddle"-a paddle designed for power and speed-and Mike was using a smaller "mid-wing."

"Hey, do you want to try my mid-wing?" Mike offered, hoping the smaller paddle might reduce the strain on Paul's shoulder. They switched paddles and continued on.

The wind shifted to the northwest and the waves built to three feet. They paddled on for another hour, with Paul setting the pace and Mike lagging behind.

"Wow! This is so much nicer," Paul shouted back.

This paddle sucks, Mike thought to himself. The waves built to four feet as the sky grew overcast and the wind shifted to the north-northwest, blowing now at 15 knots. The howling of the wind made conversation difficult; the waves broke across the kayak decks. Paul wondered why Mike was slowing; Mike wasn't just feeling sluggish-he was feeling unstable.

"Hey, hang on," Mike shouted into the wind. "Check out my boat."

Paul slowed and let Mike pass. "The stern of your boat looks like it's submerged quite a bit," he said. Paul drew his boat over to Mike's, held on to the deck rigging and pried open the back hatch cover. He peered inside. "It's half full of water!"

Just then, a large wave crashed over the two boats and nearly filled Mike's back hatch completely. The Epic has a very large back hatch-about eight cubic feet. A cubic foot of water weighs just over 62 pounds. That means the back of Mike's boat now held several hundred pounds of water, and his cockpit was filling up, too. "That was the first time I felt this could really suck," Mike recalls. "I felt myself start to sink."

"Should we call for help?" Paul asked. Between the two of them, they had three VHF marine radios and a personal locator beacon for emergencies. If they were unable to call for help with the radios, they could use the beacon, which sends an emergency signal via satellite for a search-and-rescue.

"No," Mike replied. "We can do something."

They decided to use a float bag-an inflatable sack-to try to displace some of the water. Mike held the two kayaks together while Paul blew up the float bag and tried to force it into Mike's hatch. It wouldn't budge. Paul deflated it a bit and tried again. No better. Mike stashed the deflated bag in Paul's front hatch-a decision they would later regret when larger waves prevented them from opening the front hatch again.

The T-rescue is the workhorse of any kayak instructor's repertoire. It involves bringing an unoccupied boat across the deck of the rescuer's boat, inverting it to empty out the water, turning it right-side up again, and holding it steady while the second paddler reenters. With waves of up to six feet crashing over them, Mike slipped out of his boat and Paul wrestled it into a perpendicular position and leaned far into it. He slowly muscled it up on his deck, tilting it to empty out some water as he went. It was slow going, an inch at a time, with the waves pummeling the two kayakers and threatening again to replace any water they managed to expel.

It worked. "We were both concerned," Mike recalls. "This was just getting a little ugly." Paul slipped the rear hatch cover back on and returned the boat to the water, then held it as Mike reentered and sealed his spray skirt around the coaming.

"At this point we thought, OK-we took care of that," Paul recalls. "We solved that problem."

"It was great afterwards," Mike says. "It was wonderful. I could paddle. My boat responded. I thought, Bring it on now!"

|

|

|

Their exuberance was short-lived. The wind was easily 20 knots and the waves were six to eight feet. If they continued on the same course, the wind would blow them far south of Montrose Beach. So they set a ferry angle-a direction adjusted to account for the southward push of the wind. Soon Mike was lagging again; his stern hatch was taking on water once more. They rafted up to prepare for another T-rescue, but first they decided to call Paul's wife, Kim, and alert her that they would arrive later than planned. They reached her at five, just as she was leaving work.

"He sounded like he was in good spirits," she recalls. "But he said they were having some trouble-the water was getting pretty rough."

After they hung up, Mike released his spray skirt and slipped into the cold water. He held on to Paul's kayak so they could empty out his boat again. "My thought was that if we empty it a couple more times, we should be OK," Paul says.

With Mike back in his boat, they settled in for a hard slog. Paul's shoulder was aching from all the sweep strokes he was doing to keep his boat from turning into the wind. ("I was giving him ibuprofen like candy," Mike says.) Mike was cold from his repeated immersion in the cold water; the sky was darkening, adding to the urgency of reaching land. And the hatch kept filling up, slowing their progress to two or three miles an hour and making Mike increasingly unstable in the building seas.

Then a nine-foot wave caught Mike and knocked him over. He rolled up, but another wave took him right over again. He pulled the grab loop to release his spray skirt and came out of his boat. Paul performed another T-rescue and got Mike back in his boat, but the wind was blowing harder now. It was going to be a fight to get to shore at all, let alone reach Montrose, against the overpowering force of the wind and waves. They decided to change course and head farther south toward Oak Street, hoping they could ride the waves for the five or so miles to shore.

"Swells are nice, but these were cresting and breaking," Mike recalls. "It was starting to get dark and I remember bracing through a huge wave and then the next one crested on top of me and broke."

Large breaking waves are hard to imagine until you're unlucky enough to be underneath them. Sit on the floor and picture a point two feet above your ceiling. That's the perspective Mike and Paul had of the waves that were menacing them. When a wall of water ten feet tall crashes down, it does so with enough weight and force to break a paddle, damage a boat, and even, possibly, injure a paddler. For Mike, it was Lake Michigan's ultimate checkmate.

"I just couldn't control this boat," he says. "I did a lot of swearing."

At this point, more than his boat was beyond his control. "I saw him out of his boat again," Paul says. But before he could react, a wave picked up Paul's boat and surfed him way past Mike. Paul fought back against the wind and waves to find Mike clinging to the side of his kayak. They could see the lights of the city in the distance now, but they might as well have been a mirage. Mike clambered into his half-submerged boat and sat there, up to his chest in water.

"That's it," he said, shivering. "Paul, it's a wrap. We're calling in."

It's always hard to admit that you need to be rescued. It's even harder when you're a skilled paddler with lots of training who has frequently rescued others. But it's excruciating when you're a firefighter. For 20 years, Mike had prided himself on handling conditions that had spiraled out of control. He was the one who could size up a situation, take action, set things right.

He gripped the radio, turned it on, and pressed the button: "U.S. Coast Guard from kayakers. Do you copy? U.S. Coast Guard from kayakers. Do you copy?"

Silence.

"U.S. Coast Guard from kayakers. Do you copy? U.S. Coast Guard from kayakers. Do you copy?"

Then, out of the static, a voice: "Kayakers from Chicago Police Department Marine and Helicopter Unit. Is there a problem?"

Officer Joe Kowalsky was on duty at 7:20 that evening when the call came in. It had been a quiet shift; the swim season was long over and a small-craft advisory kept most boats in harbor. The signal from the marine radio was too weak to reach the Coast Guard antennae in Milwaukee and Calumet, but it was clear enough at the marine unit building at Randolph and the lake.

"Yes," Mike told him. "We're having catastrophic boat failure and we're getting hypothermic. We request immediate assistance."

"What's your position?" Kowalsky asked.

"We're approximately two to three miles due east of the Sears Tower. We have GPS coordinates. Do you want them?"

Kowalsky wondered if this was a prank. "This guy was in real good control," he says. "It made it hard for me to envision this guy was really in trouble."

Still, Kowalsky pressed on: "Can you give me any landmarks? Look down at the water. Is there anything you can identify close to the water?"

In the darkness, they couldn't see anything specific, just the inky black water and, in the distance, city lights.

"No, it's dark. All we can see is the lights of downtown," Mike told him. Then Kowalsky overheard Mike telling Paul that they were drifting toward the four-mile crib.

"I thought you said you couldn't see anything," Kowalsky said.

"Well, I couldn't, but now I can," Mike replied.

"Let me see who I can get for you."

The radio was silent again. Mike and Paul looked at each other. "We're at his mercy at this point," Mike said. But already, two rescue boats were on their way. They were finishing their Homeland Security checks of Navy Pier and the filtration plant and immediately set out toward the crib.

About this time, Kim pulled into a parking space near a hardware store and opened the car door. Her heart dropped. "I noticed the wind. We sail, so I knew it had to be 20-plus knots. And that's when I started to get kind of panicky."

Kim called Carmen at the Agostinellis' home in Harwood Heights.

"Boy, it's really windy out there. I'm getting nervous."

"More than likely they're fine," Carmen said, to reassure her.

"I was inland and had no idea what was going on out there," Carmen recalls. "I thought, no news is good news. If anything was going wrong, we probably would have heard. But after I got off the phone with her, I started to get concerned."

Kim called Paul's cell phone. No answer. She called Mike's. No answer. She called Carmen again, who was on the way to O'Hare airport to pick up her daughter. "I tried to keep myself calm by sort of doing errands," Kim says. But she couldn't stop worrying.

Mike, meanwhile, didn't wait long before calling Kowalsky for an estimated time of arrival. "Chicago Police Department from kayakers. Do you copy?"

Kowalsky came back on. "I have two boats, a 45-foot and a 32-foot, on their way. Look for the blue light."

The kayakers couldn't see anything. They couldn't be seen. "I've got some flares," Mike told Kowalsky. "Do you want me to fire them off?"

Kowalsky checked in with officer Tom Fahy aboard the larger boat.

"Fire one off," Kowalsky said moments later.

Mike pulled one of his three pencil flares from his vest pocket, disarmed it, held it up, and tugged on the chain. Nothing. He pulled out a second one, taking extra care that the flare was fully disarmed. Nothing again. The third turned out to be a dud, too. He'd carried them across the lake for nothing.

Then the men saw a blue light bobbing in the distance. Paul brought out a bright white light and waved it back and forth above his head. "They have you in their sights," Kowalsky told them.

Within minutes, the two boats were circling the kayakers.

The rescue was a textbook-perfect operation. "It's something we do more frequently than you know," Fahy says. The officers threw a life ring to Paul and pulled the two kayakers to the back of the larger boat. It took all four officers-Fahy, Paul Zia, Joe Doane, and Dave Bryja-to get the men and boats onboard. They wrapped the paddlers in blankets, arranged for an ambulance to meet them at Navy Pier, and offered Paul and Mike their cell phones.

"Finally, my phone rang," Kim says. "I don't even remember who I talked to, whether it was Paul or Mike."

"Where are you?" she demanded.

"We're on a police boat. We've been rescued. We'll meet you at Navy Pier."

"I felt a huge sense of relief," Kim says. "I knew that they were OK."

Only then, with the 45-foot police rescue boat smashing up and down in the waves, did Paul and Mike acknowledge just how rough the water was. The boat bashed its way to Navy Pier, arriving at about 7:50 p.m. Paul and Mike refused medical attention and Kim drove them home.

"They were so quiet," she recalls. "That's not unusual for Paul, but it is for Mike. I was getting really short responses: ‘Are you hungry?' ‘Yes.' ‘Are you cold?' ‘Yes.' ‘What happened?' ‘We had some trouble.' That was all they had left in them."

When Carmen returned from the airport, she found Mike more exhausted than she had ever seen him. She put a plate of chicken and broccoli before him, but he didn't have the energy to move the fork from the plate to his mouth. He retreated upstairs and crawled into bed.

The next morning at the firehouse, his colleagues were amused by his tale of disaster averted, as perhaps only a group of firefighters can be. That evening, they came to the firehouse dinner wearing their bright orange marine-rescue flotation vests and helmets.

—

Why paddle across Lake Michigan? Why take the risk? She has claimed countless mariners; her bottom is littered with the remains of hundreds of ships that dared to cross her when she was in no mood to trifle. "I think people fail to realize how tricky Lake Michigan is and how quickly she can turn," says Commander Steve Georgas, then commanding officer of the Chicago Police Department Marine and Helicopter Unit. "People underestimate her. The winds can change so quick."

But sea kayaks are designed for big water, and serious kayakers crave it. They circumnavigate large lakes and landmasses, play in tidal currents, and train to handle every emergency imaginable. Here in Chicago, when the National Weather Service declares a small-craft advisory and other boats come in, sea kayakers go out surfing. On the water, it's truly a battle of skill and wits against the forces of nature.

Why paddle across Lake Michigan? Because it's Chicago's great horizontal challenge. Alaska has Denali; Hawaii has Jaws; Oregon has the raging Columbia River Gorge. The Midwest has Lake Michigan, and Midwestern paddlers are tired of dismissive remarks from kayakers on both coasts.

Next time, however, Mike and Paul will go earlier in the year. Next time they'll double-check that their hatches are watertight.

Next time, Kim and Carmen say, they'll have every bit as much confidence in their husbands as they had this time. Maybe more.

Next time, Paul and Mike agree, they'll go farther, say 60 miles, from St. Joseph or Stevensville, because that would be a new challenge and because, well . . .

Because that's why you paddle across Lake Michigan. Because if you have enough skill and you have the right equipment and the weather looks good, you just might make it.

And then again, you just might not.

Comments are closed.