During the heat of last year’s presidential campaign, when William Ayers emerged as a “mini demonic celebrity,” as he puts it, he remained uncharacteristically quiet in the mainstream media. He didn’t try to defend himself from being called a terrorist by John McCain, Sarah Palin, and others. He didn’t set the record straight about whether he really did “pal around with” Barack Obama in Hyde Park, as some charged.

Rather, Ayers responded only to two low-profile critics. One of them, Stanley Kurtz, a senior fellow at the conservative Ethics and Public Policy Center, argued in The Wall Street Journal that the real reason to worry about the Obama-Ayers association was Ayers’s “educational philosophy, which called for infusing students and their parents with a radical political commitment, and which downplayed achievement tests in favor of activism.” Similarly, Sol Stern of the Manhattan Institute, another conservative think tank, published a number of essays in the institute’s journal arguing that the “pressing issue” was the “harm inflicted on the nation’s schoolchildren by the political and educational movement in which Ayers plays a leading role today.”

|

RELATED ITEMS

NO REGRETS >>

REBEL WITHOUT A PAUSE >> |

Why take on the education critics? “The other stuff—that was about a cartoon character,” Ayers says today. “It had nothing to do with me. But those [articles by Kurtz and Stern] were the only things I did read.”

While the pundits and bloggers jousted over Ayers’s 1960s radicalism, he sparred online with Stern in competing postings to the education-policy blog Eduwonkette. Defending his notion of “social justice teaching” from Stern’s claim that it was a “left wing ideology,” Ayers insisted that his ideas reflected no particular political stance, that he simply advanced a style of teaching in which educators emphasize “a commitment to free inquiry, questioning, and participation. . . .”

The education debate got little attention—a frustration to Ayers, who confesses to having blind spots in his understanding of the broader culture. (In Fugitive Days, his memoir of his life in the radical Weather Underground, he admits that he expected thousands of working-class kids to join the group’s Days of Rage rioting in protest of their own, presumably obvious, oppression.) Even today, Ayers seems slightly disappointed that the campaign noise about him did not evolve into a more thoughtful discussion of education policy.

He may yet get his wish. As a professor of education at the University of Illinois at Chicago, Ayers was deeply involved with reform efforts in the Chicago public schools, particularly in the early nineties. The high point of Ayers’s direct involvement with the schools came when, as a coauthor of the Annenberg Challenge, a grant proposal that netted $49.2 million in funding for reform efforts in 1995, he helped create and fund numerous programs for teacher training and support. And in the years since then, he has maintained, primarily through his research and writing, a complicated, often contentious relationship with CPS administrators, including Arne Duncan, now the Obama administration’s secretary of education.

Though many of the ideas promoted by Ayers have become almost mainstream in school reform, he remains deeply suspicious of “accountability”—a leading principle in education policy today, but one that Ayers and like-minded colleagues claim suppresses flexibility, experimentation, democracy. As the new administration moves beyond the Bush-era No Child Left Behind effort, Ayers’s voice is likely to rise in the clash of ideas. In fact, in the months following the election, he has had a kind of rebirth in the national media, finding himself spotlighted in a number of highbrow venues, from National Public Radio’s Fresh Air to The New York Times Magazine.

* * *

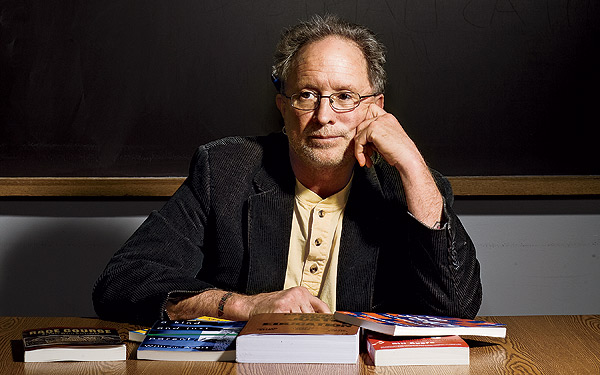

Photograph: Anna Knott

|

RELATED ITEMS

NO REGRETS >>

REBEL WITHOUT A PAUSE >> |

Bill Ayers's involvement with education goes back to his days as a radical. He worked as a teacher and school director before his time with the Weather Underground, and he has said that his teaching was close to his political activity—he hoped his students would grow up to be activists, too. After he surfaced from being underground in 1980, he got a master’s degree in early childhood education from the Bank Street College of Education in New York and a doctorate in education from Columbia University. Then he returned to Chicago, where he had grown up in comfort. He has been a member of UIC’s education faculty since 1987, and he has gained a reputation for expertise—last year, he was elected vice president for curriculum of the American Educational Research Association, the nation’s largest organization of education-school professors and researchers.

Many of his tenets are hardly revolutionary—that parents and communities should control their own schools, that students learn better in “small learning communities,” that teachers are most effective when they ask questions and facilitate projects and discussions, rather than simply lecture or drill. These ideas in particular have become components in most major school reform efforts across the country, influencing not only educators but also private philanthropists and public policymakers.

What’s more, many of his ideas have been around for years. As a preschool teacher in the 1960s, he followed the Summerhill method, a philosophy pioneered by the Scottish educator A. S. Neill in the 1920s and popularized in “free schools” around the world in the 1960s, allowing children almost total freedom in choosing what, if anything, to learn.

Today Ayers occupies a unique position in the world of education. Neither a policy wonk nor an administrator, he functions instead as a kind of populist intellectual—consulting, lecturing, writing, and training teachers, speaking always from the perspective of the classroom teacher he once was. The combination of his infamous past with his respected academic work has long made him a popular guest at universities and conferences, but now his profile seems to have been raised to another level. After a January speech at Florida State University was met with student protests, Georgia Southern University rescinded its invitation to Ayers to speak there in March “because of the increased amount of security and costs required.”

Ayers holds to an educational philosophy known as “teaching for social justice” that takes an expansive view of the purpose of schools and teachers. They exist, say Ayers and other proponents, as instruments of democracy. At their best, they turn out active, engaged citizens. Ayers sums it up this way: “All schools serve the societies in which they’re embedded—authoritarian schools serve authoritarian systems, apartheid schools serve an apartheid society, and so on. Practically all schools want their students to study hard, stay away from drugs, do their homework, and so on. . . . But in a democracy one would expect something more—a commitment to free inquiry, questioning, and participation; a push for access and equity; a curriculum that encouraged free thought and independent judgment; a standard of full recognition of the humanity of each individual. In other words, social justice.”

Unlike, say, literacy or math skills, a fluency in social justice is hard to test. Agitating outside of school for improved social conditions is not a stated goal of social-justice education, but it is frequently cited, by supporters and opponents, as one measure of the effectiveness of the teaching. But preparing kids for a lifetime of civic participation requires more than a well-constructed curriculum. It demands that students have access to the institutions of public life, that they are healthy and safe and well fed, confident that their basic needs will be met, even as they turn their attention to larger questions.

In practice, the ideals of social-justice education have been applied mostly in a limited fashion, failing to catch on in a substantial way in the urban settings where reform is needed most. For one thing, Ayers and others oppose the zero-tolerance discipline codes that often accompany efforts to improve failing schools. For another, efforts to improve standardized test scores generally mean that kids have less control, rather than more, in choosing what they study. And no major urban district has tried to partner with entire communities to bring about the kinds of social changes, like economic empowerment, that would address all the challenges facing their school-age kids.

Instead, the common thread connecting education policy today—from No Child Left Behind at the national level to local reforms in cities all around the country—is accountability, the setting of specific, quantifiable goals and the relentless movement toward achieving them, eliminating perceived obstacles, like struggling teachers, as quickly as possible.

Ayers and other social-justice thinkers are deeply suspicious of this bias for quick, directed action. They encourage experimentation and an approach that lets kids, parents, and teachers decide what to try next. In this, Ayers says, his work in education parallels the progressive approach to political organizing, summarizing his methods in both cases as: “Pay attention, be astonished, act, rethink, act again, and doubt again.”

* * *

|

RELATED ITEMS

NO REGRETS >>

REBEL WITHOUT A PAUSE >> |

It's no coincidence that the public schools in Ayers’s hometown have come closer than any other large American school district to living out the ideals of social-justice education. Ayers played an instrumental role in creating the “local school council” structure that emerged during school reform in Chicago in the 1990s, and though the LSCs have now been stripped of much of their autonomy, he continues to see them as a hope for successful reform in the CPS system. “There were all these dire predictions that the keys to the asylum were being handed over to the inmates,” he says, “but all we did was create in Chicago neighborhoods what you have in Glen Ellyn: parents controlling their schools. People who hate on school boards are hating on democracy.”

Though some of the LSCs were faulted for corruption, pettiness, and mismanagement, Ayers says, “the corruption was nothing compared to what you saw at the central office.” Mostly, he says, the councils used their budgets to hire more teaching aides, provide greater security, and buy new teaching materials.

In 1995, after five years of schools’ being governed largely by the local school councils, the CPS system was again restructured, with Mayor Daley taking direct control over a largely recentralized administration. When Duncan replaced Paul Vallas in 2001, he began a series of initiatives—closing failing schools and replacing them with new, smaller schools, including numerous charter schools—that evolved into what is now called the Renaissance 2010 program, which sets forth a goal of creating 100 high-performing public schools in designated communities of need by 2010.

The LSCs Ayers champions are far less powerful than they once were, and money from his Annenberg Challenge grant proposal stopped coming into the district in 2001. His grown children—sons Malik, Zayd, and Chesa Boudin, the last raised by Ayers and his wife, the law professor Bernardine Dohrn, following his parents’ incarceration for committing murder while members of the Weather Underground—attended the private University of Chicago Laboratory Schools, rather than public schools. In an official sense, Ayers is an outsider. Although this position leaves him open to criticism as a mere ivory-tower critic, rather than someone who is doing the actual work of reform, he sees his role as that of an academic—he refers to himself as a “thinker, analyst, trainer of teachers.” And Ayers himself still casts a large shadow within the district. In fact, his ideas are often cited as the philosophical underpinnings for new initiatives. “Renaissance 2010, the small schools movement,” says Edward T. Klunk, from the CPS Office of High Schools and High School Programs. “Bill Ayers influenced all of that. He’s there.”

Now, with the Chicago schools chief Arne Duncan leading the department of education, will Ayers’s views find their way to a larger, national audience? Ayers says his relationship with Duncan, as with Obama, is more of “knowing him from the neighborhood” than working with him as a colleague. “I’ve never actually sat down with him and talked policy,” Ayers says.

Overall, Ayers is deeply skeptical of the Renaissance 2010 initiative. He compares the closing of failing schools to the demolition of public housing projects, saying, “People are suspicious that when you close this up, there’s going to be nothing to replace it. And, with public housing, they were certainly right to be suspicious.” (In fact, for the most part, those fears have not been realized. Under Duncan’s administration, 61 schools were closed, while 75 were opened.) While Ayers is careful not to condemn the charter school movement in general, he objects to what he calls the “privatization” of some schools, turning them over to educational management companies that oversee them via special charter arrangements. His criticisms seem to have been a thorn in Duncan’s side.

In 2006, Duncan wrote a long, personal response to a journal article Ayers and another small-schools advocate had written, criticizing the program. Duncan urged the two academics to “embrace” the policy. (Duncan declined for this article to comment further on Ayers’s work.)

For his part, Ayers says he has never been an embracer and, anyway, “CPS policies in the past have not warranted even a tepid hug.”

In some sense, it would be impossible for a big school district to live up to Ayers’s ideals. His philosophy resists standardization and aggregation—he derisively refers to this need to find a single, right way to do things as a “Walmart” approach to education—in favor of unique approaches for every “learning community.” This neighborhood-by-neighborhood approach is the sort of thing that makes conservatives and business-minded thinkers nuts: As they work to find solutions that “scale,” Ayers reminds them of all the places where their ideas won’t fit.

Though he praises Duncan for being a pragmatist, Ayers sees the new secretary of education as being fundamentally limited by a need to find a single set of “right” answers. Indeed, he responded to Obama’s appointment of Duncan to the cabinet position with an essay, published on The Huffington Post, in which he described Duncan and the other top candidates [Michelle Rhee, Joel Klein, and Paul Vallas] for the job as “four failed urban school superintendents,” who “have little to show in terms of school improvement beyond a deeply dishonest public relations narrative.”

“That was a little mean,” Ayers laughingly reflects now, though he seems to be positioning himself to take up a kind of loyal opposition role outside the Duncan-led department of education.

* * *

Forty years after the turbulence of the late sixties, Ayers insists he has no particular investment in what kids grow up to advocate for, just as long as they find a way to engage with society and work for the betterment of their community. He insists that “teaching for social justice” contains no partisan agenda, but he gives himself away slightly when asked about local school boards that, say, want to keep evolution and sex education out of the curriculum. That sort of empowered local control, he makes plain, is not what he has in mind. “Inquiry, imagination, evidence, and argument are essential,” he says curtly. “I don’t feel like those are ideological. All you’re doing is asking questions.”

As an example, Ayers describes the anti-obesity measure sponsored by Arkansas’s former governor Mike Huckabee that required report cards in Arkansas public schools to include a student’s body mass index (BMI) in addition to his or her grades. Ayers takes it as an article of faith that any right-thinking person would find this measure ridiculous. “Surely,” he says, “‘Is he fat?’ doesn’t belong in the same category as ‘Can he read?’” But instead of launching a highly visible protest or simply refusing to fill in the box, he says, he would involve his students in a discussion of the requirement.

“Here’s what I’d do, if I were a teacher in Arkansas,” he says. “I’d develop a curriculum for my kids that looks at who thought up this BMI measure, who’s got the contract for serving lunches in our school, what kind of physical education do we have, how many sports teams are available to join. You generate a pedagogy of questions. That’s what good teachers do.”

His guiding principle, he says, is that society should want for all its children exactly what the most privileged and wise parents are always saying they want for their own kids: an educational experience in which their child is seen and recognized as an individual. “I can’t imagine I’m saying anything that anyone really disagrees with,” he insists pleasantly, sounding far more like the concerned grandparent he now is than the radical outlaw he once was.