Waves pummeled Todd Rosenthal’s second-floor condo on Eastlake Terrace in Rogers Park during a mid-January storm. Not spray. Literal waves. He helped a neighbor board up her windows, like coastal residents do during hurricanes, to help stanch the water seeping in. It’s now an unspoken rule that residents of their 100-year-old building text each other during storms to make sure everyone is OK.

As wind and water have thrashed the lakefront over the past year, we’ve all seen photos on social media of the damage to public beaches. Homeowners along the shore are struggling, too, as Lake Michigan flows into their basements, chips away at their foundations, and batters their windows. In some cases, particularly on the Far North Side and in South Shore, they’re approaching a Catch-22: Staying put could become cost prohibitive because of rising building assessments for water-related fixes and additional self-funded repairs on their units — but finding a buyer willing to gamble on a lake that’s changing in ways we’ve never seen could pose a challenge.

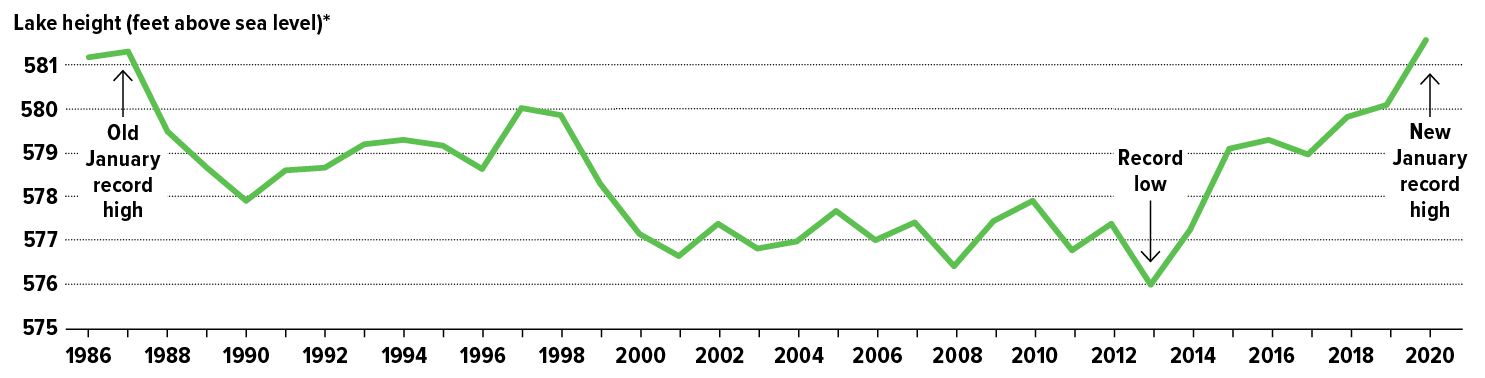

The lake sat, on average, at 581.6 feet above sea level in January, breaking the previous record for the month set in 1987 by three inches and rising 5.5 feet above its lowest January average set in 2013. (The all-time record average, 582.35 feet, was set in October 1986.) Combined with those high water levels, storm-driven waves like the 23-foot ones that hit Chicago in January are able to claw farther onto shore — and closer to where people live. In February, in response to the storm, Governor J.B. Pritzker issued a state disaster proclamation, joining Mayor Lori Lightfoot in seeking federal relief to address $37 million in damage to the Cook County shoreline.

Alderman Maria Hadden of the 49th Ward, which includes the Rogers Park lakefront, says she’s heard from “tons” of worried property owners (though her office hasn’t tracked exact numbers) since beach erosion started intensifying last summer. Waves crashed so hard into buildings that residents contacted her office, saying it felt like an earthquake. Renters wondered what kind of responsibilities their landlords had to protect them. Residents have asked about financial relief for pricey reinforcements to keep the water out of their homes, though at this point the city has nothing to offer.

Rosenthal, for one, has installed a hurricane-proof door and new windows to replace leaky ones, to the tune of about $26,000. Regular homeowner association fees have so far covered all other water-related building fixes, including vapor barriers and new drywall installed in units on the building’s east side after water leaked through the brick. “At this point, we’ve found a solution, and we’ve implemented it, and it seems to be working,” says Rosenthal, adding that, despite the expense and uncertainty, he doesn’t anticipate ever wanting to move from his home. “It’s like living on a resort.”

Farther down the lakefront, Juliet Dervin moved into her ninth-floor South Shore Drive co-op, which is directly next to Lake Michigan, about a year ago. After a storm in late October, she got scared. “Every time a wave would hit the seawall, you could feel the shake in the building,” she says. She sits on her building’s co-op board, which held an emergency vote in December on short-term measures to fortify the building, including tearing out the damaged terrace, filling it in with rubble, and topping it with concrete blocks to form a barrier. The building also replaced a small landscaped courtyard with sandbags to keep water from approaching the foundation. Dervin says her building’s residents voted last year on an assessment increase for façade improvements to fix weather-related damage.

While Dervin acknowledges that “this has the potential to be extremely expensive,” she says she, like Rosenthal, is not going anywhere: “I’m committed to South Shore. I’m committed to my building.” She joined the South Side Lakefront Erosion Task Force, which was organized in December by state representative Curtis J. Tarver II, state representative Kam Buckner, and 7th Ward alderman Greg Mitchell to lobby for projects such as breakwalls.

If what’s happened in other parts of the country is an indicator, all this could put a squeeze on lakefront home values. “We have seen prices not grow as fast in areas that are more prone to flooding from hurricanes, for example, than areas further inland,” says Realtor.com chief economist Danielle Hale.

Connie Abels, a real estate broker who heads RE/Max Premier NorthCoast, has begun giving tough love to sellers of lakefront properties in Rogers Park. With so much still up in the air on repair costs and preventive measures, she’s telling them to be ready to lower prices, put up an escrow to cover damage that’s been incurred, or provide a credit. At the same time, she thinks the shoreline will always be considered prime real estate. “I have clients currently in the process of purchasing along the lake,” she says. “I cautioned them on the unknown, and you know what? They want to proceed.”

The tempestuous conditions are starting to give other potential buyers pause, though. Brady Chalmers grew up in Rogers Park and always hoped to live on Eastlake Terrace. “When you’re a kid from over here, Eastlake Terrace is exactly where you want to make it to,” he says. In fact, he did, renting on the street for multiple years. But when he and his wife thought about purchasing a first-floor condo on the east side of the street a few years back, potential flooding in the unit was one of the reasons they didn’t move forward. “If you look at what the lake did to the beach, and then you look at the fact that there are buildings in that water,” he says, “I don’t know how they’re still standing.”

Waves of Change

Ups and downs are a normal part of Lake Michigan life. The rise since 2013, however, has been unusually fast.

SOURCE:U.S. Army Corps of Engineers