When I pulled into the yard of Paula Camp’s elegant Victorian home, a tall figure started marching toward my car.

“Hello and welcome,” said Camp, wearing a gray hoodie, rubber boots, and black jeans. “I’d shake but my hands are pretty sticky.”

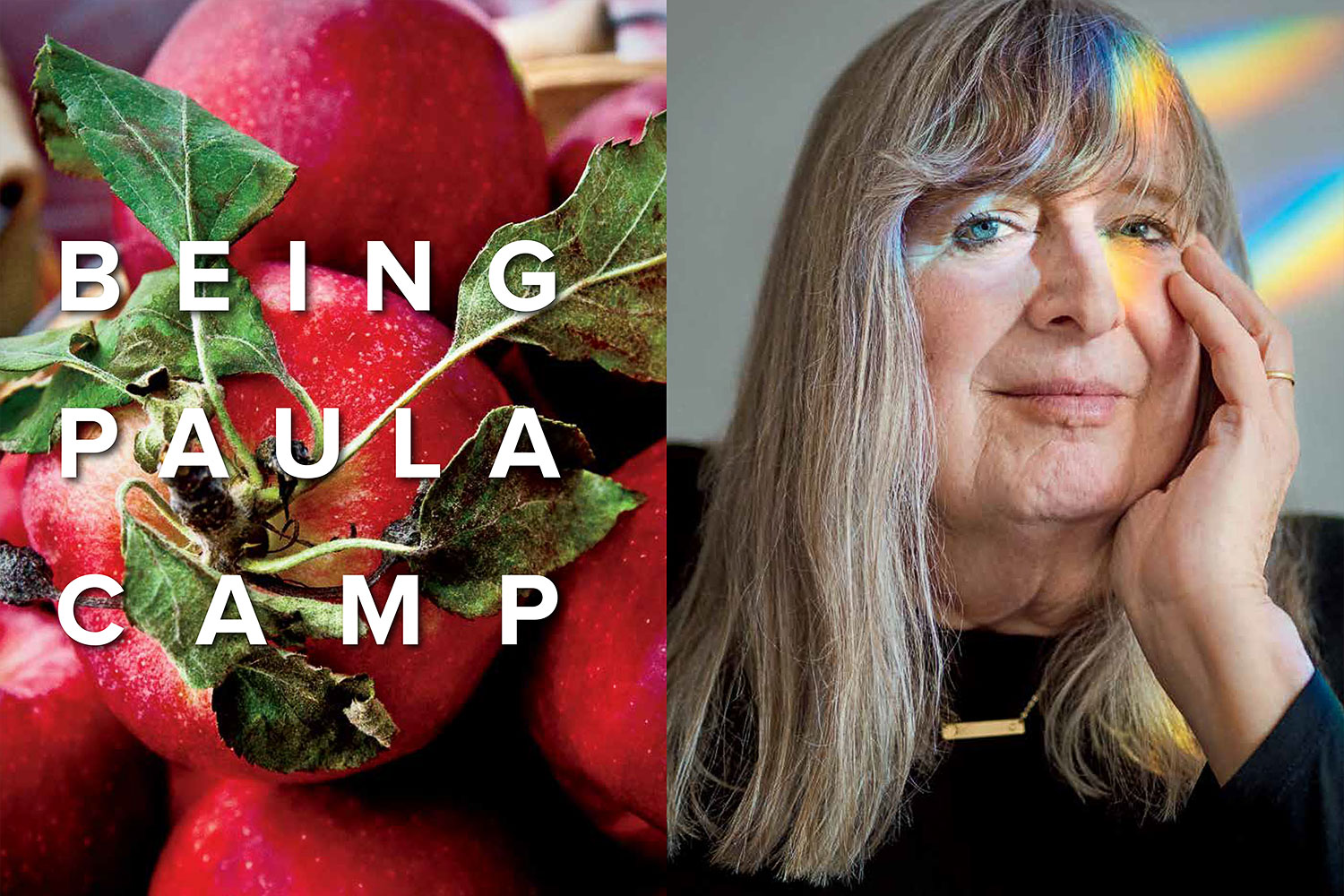

It was a crisp fall day at Carriage House Ciders, the fledgling business Camp started in 2020 out of her house in Benton Harbor, Michigan. She’d been pressing apples all morning. As I breathed in the sweet, fruity air, Camp showed me giant pallets of heirloom apples, with names like Arkansas Black and Newtown Pippin, and demonstrated the processes of pruning, pressing, and filtering. Finally, she led me to a barrel room, where she and a friend hoisted a giant bucket of the golden juice and carefully poured it into a heavy oak cask.

I quietly pulled out my phone to capture the moment. Camp looked up with a hint of self-consciousness.

“Monica, I’m afraid you’re not catching me at my most feminine,” she said with a fluty giggle.

I laughed back, but I could tell she wasn’t entirely joking.

See, these days, Camp takes her femininity very seriously. But not long ago, it was something she was terrified to acknowledge. That’s because, for most of her 73 years, people knew her as Paul Camp, who served as the Chicago Tribune’s exacting restaurant critic and ascendant lifestyles editor through much of the 1980s.

Camp has largely stayed out of the public eye since quitting the newspaper three decades ago, even as she remained in publishing and raised a family with her wife, Mary Connors. So when many of Camp’s old Tribune colleagues discovered her transition — through LinkedIn and Facebook profiles showing a familiar face with stylish long hair and lipstick — it came as a shock.

“There were simply no touchstones or examples to guide me. My reality was a long time unfolding.”

They told me they remembered Camp as an ambitious and inspiring editor, but also as an arrogant and macho boss with a ferocious temper. Looking back, Camp says she deserved her reputation but that it came from a secret she kept closely guarded. “My anger spasms were driven by being ‘forced’ to be something and someone I was not,” she told me. This turmoil dogged her through three marriages, a series of high-risk career moves, and four therapists before Camp finally came to terms with her inner struggle and began to transition six years ago.

Camp says Connors, her wife of 33 years, “showed me the true meaning of love by staying at my side even though I put her through hell.” Connors is also standing by her as Camp delves into her new business in a new field in a new state, a venture she’s taking on as “an elderly trans woman,” as the former food critic bluntly puts it.

Over five months, Camp and Connors sat for a series of interviews and follow-up conversations by email and Zoom. Our talks got raw and honest, even painful, yet the couple stuck with it. It’s important to Camp to serve as an example for others because she herself didn’t have any early on. In the past, she notes, “they put people like me in jail or, worse, into state mental institutions.”

“I knew I was different when I was young,” she continues. “Perhaps it was the time I grew up in, but I did not know I wanted to be a woman. There were simply no touchstones or examples to guide me. My reality was a long time unfolding.”

One of Camp’s earliest memories is of trying on her mother’s high heels when she was 4 or 5. “I was clomping around her bedroom,” says Camp. “My [older] sister was there, in her high heels, and they were all giggling and thought it was really cute.”

Her father, however, didn’t find it cute at all. “He said, ‘No! No more,’ and I never did that again,” she recalls. “I remember, to this day, feeling a sense of shame but not understanding why this was a bad thing.”

Even so, as Camp got older, her interest in wearing women’s clothes endured. When she was in fourth grade, she would raid her mother’s closet for things she could wear when no one else was home — bras, girdles, and heels. Camp even made attempts at changing her body: “In sixth and seventh grades, I pulled and pulled on what I wanted to be my breasts in private, trying to make them grow.”

The family lived in East Alton, Illinois, a small semirural town not far from St. Louis. Camp’s father, Charles, worked as a postman; her mother, Jean, as a reporter for the local paper. “My mom wrote profiles, she covered the women’s club and various church goings-on,” Camp recalls. “But if something like a tar truck blew up and another reporter wasn’t available, she was out covering that.”

Despite Jean’s love of reporting, she discouraged her younger child from journalism because of the “short pay and long hours.” So when Camp enrolled at Washington University in St. Louis, she did so as a music major, playing the trombone. Soon, though, she realized she lacked the hunger for a professional musical career — particularly the requisite hours of practice. She switched her major to political science and began running the campus literary magazine with her roommate.

While finishing up her bachelor’s in 1971, Camp married her college sweetheart, Terry Yokota. After graduation she quickly landed a job as the editor of the St. Louisan (now called St. Louis magazine), “mostly,” she says, “because an editor came down with pneumonia” and the owner needed a fill-in. It was a heady time. Camp was in her early 20s, a newlywed, the editor of a city magazine, and the owner of a large fixer-upper mansion she happened upon in St. Louis.

At home, though, Camp continued her secret life. “[My wife] was tall and skinny, and I was also tall and skinny at the time, so I could wear her clothes,” she recalls. “And I did, but only when she was out.” Camp says she was sometimes able to stifle the urge to dress up for months or years, but “I was always a keen observer of all things feminine — mannerisms, activities, speech, makeup, and, of course, clothing.”

At the St. Louisan, Camp boosted the magazine’s arts coverage and served as both editor and dining critic. But she lost her job, as she remembers it, after choosing the wrong spot to critique: “I learned it was not a good idea to write a bad review about your boss’s best friend’s restaurant.”

After a stint working at a friend’s ad agency, Camp took a gamble and bought a local alternative paper called St. Louis Today in a highly leveraged deal. Not long after the purchase, the mid-’70s recession hit and the paper folded.

“It was a very low point in my life,” she says. “Terry had left me [after Camp admitted to infidelity], I had to sell the house, and I lost the business. It was the only time in my life, having nothing to do with my gender, that I actually considered taking my life.”

In 1976, Camp moved to Philadelphia to work for a trade publication covering specialty advertising products. There she married Lori Breslow, whom she’d met in St. Louis, and in 1978 the couple left for New York City, where Camp took a job with Fairchild Publications. In addition to putting out the fashion titles W magazine and Women’s Wear Daily, the company also published an industry journal called Home Furnishings Daily. Camp became its housewares editor.

While at Fairchild, the ever-creative editor dreamed up a new cookware and gourmet foods magazine called Entrée. It is now defunct, “but it made tons of money for a while,” Camp says. She profiled famous chefs, including Julia Child and Jacques Pépin, who cooked for her at their homes.

Those interviews got the attention of the Tribune. After the newspaper republished the Pépin story in 1981, an editor inquired whether Camp would like to come to Chicago to revive the ailing Taste section of the Sunday Tribune.

Camp agreed but insisted on giving three months’ notice, since Entrée had just launched and she wanted to help Fairchild with the transition. But a funny thing happened during those three months: By the time Camp arrived in Chicago, Taste no longer existed. “They’d killed the section,” recalls Camp. “So there I was, an editor without a portfolio.”

The Tribune suggested Camp join the copy desk, a prospect the admitted bad speller found terrifying. So she pitched them a counterproposal. “I said, ‘You know, this is a great food town. Why don’t we have a restaurant critic?’ And before you knew it, I’d talked my way into becoming the restaurant critic.” She pauses, then laughs. “Of course, I didn’t tell them that I’d gotten fired from a restaurant critic job before.”

Camp was thrilled to cover her new city, one with incredible culinary diversity and enormous portions. “I thought I’d died and gone to heaven,” she says. “I’d taken cooking courses but didn’t really know food, so I was learning on the job again. It was fun because I think that’s the epitome of good criticism — that you come in with a blank slate and open eyes, so you represent the average diner.”

It didn’t take long for Camp to find confidence — or the acerbic streak that often characterized her reviews.

Nick Nickolas wasn’t the only restaurateur who got cheesed off by a Camp review. She says another sent a message that he would break her kneecaps — a threat she took seriously.

“One of the seven ‘heavenly combination’ plates was far from heavenly,” she wrote in an assessment of Jose D. McMillan’s in Mount Prospect. “The enchilada resembled an enchilada all right. Unfortunately so did the chile relleno. The staff assures everything is prepared fresh daily. If so they might as well go back to microwaving frozen entrees. The taste and texture aren’t much different.”

In a review of Don’s Fishmarket and Tavern in Skokie, Camp pronounced the wait staff “rather obtrusive” and said one server “seemed hyper and had a tendency to rush off.” And the house fish platter? “Simply boring” and “p-l-a-i-n.” The quail at Evanston’s Va Pensiero, she wrote, was “overwhelmed by the prodigious amounts of pancetta, which in turn produces an overly salty vinaigrette that would give a cardiologist nightmares.”

Camp covered all corners of Chicago’s dining scene, reviewing storefront joints and high-end French restaurants using the same four-star scale. And she wasn’t afraid to take on her own critics, either. In 1987, Nick Nickolas of Nick’s Fishmarket — one of the city’s hottest restaurants — complained in an industry trade magazine that his place received just two stars, the same as Mike Ditka’s new namesake eatery. “What he knows about restaurants wouldn’t fit in his jockstrap,” Nickolas wrote. “If that restaurant is still there after football season, I’ll eat my pigskin.”

The next month, Camp penned a scathing rebuttal in the Tribune, explaining that her four-star system rated restaurants against analogous competitors — and gleefully noting that Ditka’s was still in business after football season had ended. “Get some salt and pepper, Nick,” she wrote. “You’re gonna need it.”

Nickolas wasn’t the only restaurateur who got cheesed off by a Camp review. She says another sent a message that he would break her kneecaps — a threat she took seriously.

The acrimony also extended to the Tribune newsroom, where Camp, juggling dining reviews with her role as the lifestyles editor, was known as a talented but turbulent presence. Retired Tribune dining critic Phil Vettel recalls a boss who “could be tough and didn’t mind getting loud — but there was always a rationale.” Of Camp’s legendary “ass chewings,” Vettel adds, “I used to tell young reporters that if they were still standing after four minutes, they were golden.”

That’s because Camp had a reputation of delivering the bad news first. The editor once called Vettel into a meeting and immediately blasted his work ethic and professionalism. “I was thinking, Oh shit, I’m in real trouble,” Vettel recalls. “But then the next thing I hear was, ‘We want you to be the dining critic at the Chicago Tribune.’ ”

In terms of job security, it didn’t hurt that Camp had handpicked Vettel for the job. “Because if people wanted to take shots at me, it was like they were taking shots at the editor who appointed me,” says Vettel. “And no one picked fights with Paul Camp.”

When longtime Chicago newspaperman Rick Kogan arrived at the Tribune in the late ’80s, he perceived Camp as “arrogant and ambitious,” so he kept his distance. Retired reporter Charles Madigan has similar memories but says, “It’s crucial to remember that these traits that may seem like flaws today — they were actually valued and even rewarded in Tribune editors back then.”

Indeed, Camp’s volatile behavior didn’t stop her ascent at the Tribune. Even while she was reviewing full time, she was given more responsibilities overseeing food, home, and fashion coverage while launching the paper’s new Style section. And after she shed the critic job, Camp says, Tribune brass telegraphed that she was being groomed for leadership. These signals included regular confabs with editor in chief Jim Squires, meetings with the ad department, and shifts as the night news editor. “It was clear to me that the intention was for me to get a more well-rounded résumé,” Camp says.

When we spoke in downtown Chicago this winter, Camp suggested her quick temper came from her desire to make the Tribune better. But a few days later, she wrote in an email, “I think [the anger] came from fear of actually being me. That, and the fact that I needed to be in control. If someone is hiding something it really helps to be in control of the situation. I was hiding something that felt huge.”

Camp says she “overcompensated,” presenting herself as macho for fear of letting her vulnerability show. “I did everything in my power to act like and prove I was a man,” she wrote. “Heck, I was trying like hell to prove it to myself … and I could convince myself for a while but my need to be feminine kept creeping back and taking over. I was deeply f-ed up and in denial.”

She maintained that denial at home with her partner, Mary Connors. They had both worked at Fairchild Publications in New York and moved in together after Camp’s second divorce. Connors had relocated to Chicago to be with Camp but also to take a job as the Midwest editor of Adweek. Despite being a savvy journalist whose job, she says, “was separating fact from fiction,” she had no idea what her partner was hiding.

The couple lived in a large Wicker Park apartment, where Camp kept a few “feminine pieces of clothing” squirreled away to try on discreetly. Still, sometimes she would slip. One morning, a colleague at the Tribune looked at Camp’s face and asked if she’d been in a play. “I realized I still had mascara that I hadn’t properly removed from the night before and, you know, was mortally embarrassed,” Camp recalls. “I turned heel and went to the restroom to get this stuff off my face.”

Dressing as a woman, Camp says, helped her relieve the growing pressure she was feeling at the Tribune. “The more stress and responsibility I took on, the more I absolutely needed to feed my femininity. It calmed me. It released some of the tension.” It also caused her to feel shame, which in turn created more stress — “a vicious circle,” as Camp puts it.

In 1989, the pressure at work had peaked, and Camp’s personal life was hit with a series of seismic changes: She and Connors got married, Connors became pregnant, and Camp’s parents died within two months of each other. She ended up quitting the Tribune in April 1990.

Camp was known as a talented but turbulent presence at the Tribune. “I did everything in my power to act like and prove I was a man.”

“I’d lost my mind. It was totally illogical — the worst career move I ever made and totally driven by fear and anger,” Camp says. “It was the trauma of my parents’ [deaths] and my fear of things getting beyond my control.” The secret she was keeping weighed on her: “I feared that I might be the freak of nature that society said people like me are and that I had worked so hard to avoid showing myself to be.”

In this storm of emotions, she says, “I lost my mind.” The resignation baffled everyone around her, including her new wife, but Camp wasn’t ready to confront what was really behind it. So she kept it buried.

The storm passed, and Camp moved on. The couple welcomed a son, Conor, prompting Camp to find new work. She bounced around a series of jobs in corporate publishing before being chosen to lead the syndication division of the Canadian newspaper giant Thomson Corporation, working from Chicago. In 2001, after the company sold off its papers, Camp created Content That Works, a syndication company of her own, which produced bridal, home, shopping, and garden content for newspapers.

Connors eventually left her job at Adweek to help run the new company, which grew to employ 15 staffers and a stable of 70 freelance writers. But by 2016, Camp and Connors, then in their 60s, were ready for a change, so they sold the company to Evening Post Industries in Charleston, South Carolina.

“We worked hard to build a brand, had nearly $1.5 million in sales, weathered the Great Recession, and were aware the future of the newspaper business would be difficult,” Camp says. “I had this pipe dream of opening a cidery. Mary wanted to write more, edit and supervise less.”

Something else had been bubbling inside Camp. And a few months before the sale, it finally burst.

In the autumn of 2015, the couple were spending a weekend at their second home in Benton Harbor, Michigan. While Connors was reading in the kitchen one night after dinner, Camp, fueled by wine, hatched an idea. Giving in to an urge she’d been suppressing for decades, she went upstairs, put on a black dress and some makeup, and came back down to take one of her biggest risks yet.

Camp presented herself to her wife as a woman.

“I think it was me wanting to be honest with Mary, and screwing up my courage to do that,” Camp recalls. “It is really not the way to do it — and I now certainly recognize that — but at the time, I thought, OK, let me show myself. I was just experiencing this wave of really strong need to be who I was. It’s hard to explain it with words, but this is something that, I think, is very common for people who have gender dysphoria, and the longer it goes without being satisfied, the stronger the impulse comes. And against all reason, you just say, Screw it. I’ve got to do this.”

Camp says she hoped to come off as “alluring and attractive.” That’s not the response she received.

“I just about fell over,” Connors says. “I was horrified. I think I said something like, ‘Did you really think I would like this?’ I mean, how do you remember the painful, stupid words that you said? At the time, I felt it was all about me. We both ended up crying.”

Instead of feeling relieved afterward, Camp was “totally embarrassed and ashamed.” The episode left them both so shaken that, Camp says, “we didn’t talk about it for months and almost pretended it never happened.”

Still, Connors was thinking about it — a lot. The revelation made her reassess a million conversations and moments from the nearly three decades they’d been married. “It’s pretty sobering to suddenly look back on your life and know that you couldn’t see anything,” she says.

I ask if the revelation ever threatened to end her marriage.

“I really don’t know how to answer that. I felt so many visceral ways, including great anger,” Connors says, before taking a very long pause. “When you know someone for as long as I’ve known Paula and have so much in common, including a child that we are crazy about — well, I wasn’t up for slamming the door to make a big dramatic statement of how angry and challenged I felt.”

So the couple pressed ahead without another mention of what had happened that night in Michigan. To help smooth the handoff of their company, they moved to Charleston. It was there that Camp grew depressed. She found a local therapist, but just as she had with her three previous therapists, Camp intentionally avoided any discussion of gender.

“I tried once again to focus on all of the things bothering me that were not about possibly being transgender. [The therapist] finally stopped me in my tracks and asked, ‘Why are you really here?’ ” Camp recalls. “After six decades of hiding, I finally admitted to [a professional] that I might have a few gender issues.”

The therapist did not push her patient to transition. Instead, she assigned reading materials, books like Gender Outlaw and The Transgender Guidebook. A few sessions in, she suggested Camp start going out in public as a woman to see how it felt. On the way home that day, Camp purchased a skirt and a couple of tops from Lane Bryant. Later she bought a wig, makeup, and sandals.

One night after work, trembling and uncertain, Camp ventured out for the first time dressed as a woman. Soon it became her nightly routine, and on weekends she would explore Charleston like this for hours. Although the walks were liberating in some ways, they also offered a glimpse into how cruelly the world treats transgender people.

She recalls passersby whispering, “That wasn’t really a woman, was it?” and parents dragging their young children to the other side of the street. In the supermarket, a man outed her to other shoppers. Another time, two firefighters at a store started loudly jeering her. “In an act of kindness, the checkout clerk taking my payment wrapped my hand in hers and told me, ‘Keep being cool’ — advice I followed even as the ridicule escalated as I made for the door,” Camp says.

Connors had been spending most of her time in Chicago, getting their Lake View home ready to sell. When she returned to Charleston, she was startled by her spouse’s transformation. Determined to be supportive, she joined Camp on her walks around the city. “But it was very hard for me,” Connors says. “It was also hard for her, but there’s a part of it that strengthened her to do that. I was paranoid, and I felt like everyone was looking.”

Connors says a turning point came when she accompanied Camp to a transgender support group in Charleston. She heard the stories of other trans women, many of them ex-military, who were finally living their truth. One of them, Connors recalls, compared telling her family that she was trans to the detonation of an IED — an explosion that took everything from her life, prompting her wife to leave and her children to back away from her.

Connors finally saw the situation in a different light. “I mean, this is not something that you would choose to do. I’m thankful that I understand that now,” Connors says with tears in her eyes. “I don’t think anyone should be reviled or ridiculed for saying who they are and wanting to be who they are. I’ve always thought Paula was a remarkable person, and now she’s, in a way, more remarkable.”

Though it had not gone as planned, the revelatory moment in Michigan was when Camp realized she would eventually transition. Her therapist knew when she saw her patient undeterred by those jeering firefighters. Soon after, she referred Camp to a hormonal therapist in Charleston, but the wait for an appointment was long.

So, in 2017, Camp returned to Chicago to visit Howard Brown Health. Despite being “a little scared” that she would run into someone she knew there, Camp felt welcome and at ease at the Lake View health center, one of the few in the city with a team focused on LGBTQ geriatric care. On that first visit, she was prescribed hormone pills, which she started taking as soon as she got to her car.

“Suddenly, within weeks, the calm I sought all of my life wrapped around me like a big, warm hug,” Camp says. “I never turned back.”

Connors confirms that her partner has become a gentler soul these days. “This is actually Paula the person,” she says. “I’m not sure who that was before. This person is more thoughtful and has less anger. It was almost like performance art, that anger.”

Not everyone has been so understanding. Camp says her best friend of 40 years stopped talking to her. And having two mothers of the groom at their son’s 2019 wedding was a nonstarter for their future daughter-in-law, who knew her religious parents would object.

Camp was crushed when she got the news over dinner one winter night at the Silver Harbor Brewery in St. Joseph, Michigan. “I think her words were ‘You cannot wear a dress at my wedding,’ ” Camp remembers. “And I immediately burst into tears and started bawling at the table. People started looking at us strangely, and Mary and Conor hugged me. Eventually I regained my composure, but that’s the way it came down.”

For the wedding, Camp dusted off an old Armani suit, which no longer fit because of the hormonal changes, and pulled her hair into a ponytail, “like the ’60s hippie I was not.” She justified her decision as avoiding a distraction, but it angered many in the Benton Harbor trans support group that Camp had started.

“You will do anything for your kids,” she says. “But I made it clear that this would be the last time I would present male. It was. I have been myself ever since.”

At Camp’s cidery on that day last fall, I watched as half a dozen friends and family members prepared and pressed apples amid lots of laughter and singing. After a few hours, Connors called us in for toasted cheese sandwiches and creamy squash soup, while Camp continued working outside.

“Just a few more batches,” she said with a smile, “and then I’ll join you.”

“This is actually Paula the person,” Camp’s wife says of her now. “This person is more thoughtful and has less anger. It was almost like performance art, that anger.”

The couple bought the rambling Victorian in the mid-1980s, when Benton Harbor was a hub of the crack trade and was considered one of the most dangerous cities in America. They spent decades rehabbing it and now live there full time, and they’ve cleared out a century’s worth of junk in its carriage house to make way for the cidery.

Camp started making cider for friends and family after Jacques Pépin served her a homemade batch in the early ’80s. When she decided in 2016 to start her own craft cidery, she sensed an opportunity in the marketplace, but she also had something to prove.

“Friends told me not to do it,” she says. “I would be opening myself up for ridicule and perhaps worse. Bankers were skeptical, to say the least, and would not fund us. But I wanted to prove that an elderly trans woman could successfully launch and run a business. I want to be an example of what’s possible.”

Carriage House Ciders began selling six variations of cider in 2021, and last fall it produced about 1,200 gallons. This year Camp aims to release eight to 10 new ciders, including one inspired by Pépin’s original recipe. Sales are currently online only, but an outdoor tasting room in Benton Harbor is in the works. She’s also planning days where visitors can tour the cidery, help press apples, and stay for dinner.

I got a delightful taste of those dinners on my visit. After a cider tasting on the porch, we moved into the large but cozy tin-ceiling dining room for trout and brisket (smoked by Camp), a green salad, bucatini in tomato sauce (using Italian cookbook author Marcella Hazan’s buttery recipe), and roasted vegetables. Having spent a decade being served by Chicago’s finest chefs and waiters, Camp has jumped to the other side of the hospitality equation.

Camp and Connors were hosting a group of friends, mostly in their 20s and 30s — some had worked at the couple’s content agency, and others were in the wine and cider industries. Camp popped in and out bearing new platters of food. Connors, who’d recently had surgery, didn’t talk much but made sure everyone had what they needed. When they both finally settled into their chairs, side by side, they listened more than they spoke. But they also finished each other’s stories and remembered old times with laughter and affection. They struck me as one of those rare long-married couples who don’t just love but actually still like each other. The night six years ago in this same house that could have ended their relationship instead seems to have renewed it, deepening their appreciation for each other.

“It’s never too late to be who and what you are,” Camp tells me, reflecting a few days later. “It’s never too late to do what you want and are meant to do.”

For the hard-charging journalist turned genial cider maker, that means continuing to take on new ventures, like she did 40 years ago when she talked her way into a big-city dining critic’s job. But now she’ll be doing it as someone finally at peace in her own skin.

“It took me a long time,” Camp says. “But I am one of the luckiest people on earth to be where I am today, to be the woman I have always been.”