Next to Gate 4 of Guaranteed Rate Field, home of the White Sox, is a bronze bust of the late governor James R. “Big Jim” Thompson. It’s an homage to the wily politician who in 1988 forged a government-backed financing deal — over significant political opposition — to bankroll construction of that stadium and stop the franchise from bolting to Florida. “He kept the White Sox in Chicago,” reads the bust’s inscription.

These days, the White Sox may want to stay in Chicago but not necessarily in their 33-year-old publicly supported stadium, where a team-friendly lease — another byproduct of Thompson’s dealmaking — expires in five years. As we know, the Sox are talking about building a state-of-the-art baseball palace in the 78, a nascent development in the South Loop that backers say will turn a mostly barren 62-acre site into a residential, entertainment, and commercial district.

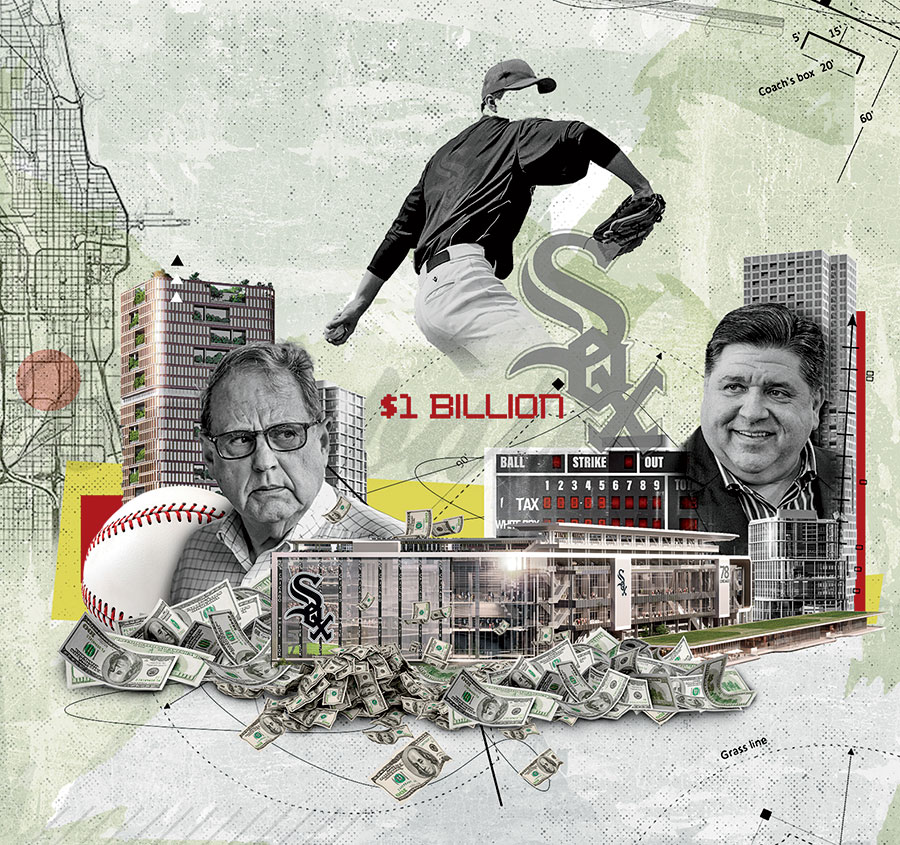

The excitement for a new stadium seems to grow daily. But before the project can move forward, Sox owner Jerry Reinsdorf and Related Midwest, the 78’s developer, will have to address mounting questions and concerns raised by Governor J.B. Pritzker, Mayor Brandon Johnson, activists, and community groups.

Chief among them: How many, if any, public dollars and cost breaks should be poured into a new stadium? Reinsdorf told Crain’s Chicago Business that he’s seeking $1.1 billion in public subsidies for the ballpark itself, plus up to $900 million in related infrastructure work. “Are we talking about more taxpayer investment? And are we going to risk creating a white elephant that just sits in Bridgeport?” asks Marj Halperin of One Community Near South, a recently formed coalition of neighborhoods asserting that residents must play a part in any public-private ballpark negotiations.

“They can talk about jobs, economic impact, or whatever, but they can’t make it pay if they use only their own money.”

— Allen Sanderson, University of Chicago professor

While everyone knew the Bears were stadium shopping, the Sox’s announcement came as a surprise. Despite the team’s middling record on the field of late, its value has climbed since a Reinsdorf-led group bought the Sox in 1981 for $19 million. The Sox are now worth an estimated $2 billion, a valuation based in part on a lease that limits the amount they owe the Illinois Sports Facilities Authority, a city-state entity that owns Guaranteed Rate. For the first 10 years, the Sox paid no annual rent if attendance fell below 1.2 million, which it usually did. Under the current terms, the team forks out $1.5 million annually but controls revenue from ticket sales, concessions, parking, and merchandise. The city and state each contribute $5 million annually to Guaranteed Rate — money that’s generated by a tax on hotel rooms.

With this sweet lease winding down, Reinsdorf is casting a wandering eye toward the 78, located along Roosevelt Road and the South Branch of the Chicago River. Related Midwest recently issued glossy renderings of a gleaming, high-tech stadium set against the Chicago skyline and amid a bustling neighborhood. Those images amped up many Sox fans on social media and sports radio and elicited encouraging comments from the mayor, who says he’s open to discussing the move but needs to know more. Major League Baseball commissioner Rob Manfred has endorsed the relocation, telling Crain’s it would be a “game-changer.”

Related Midwest says the stadium and surrounding development would constitute a $9 billion investment and create $4 billion annually in economic impact while producing thousands of jobs. But funding it would mean more ISFA bonds, as well as a special state taxing district for the 78 to support those bonds. “They can talk about jobs, economic impact, or whatever, but they can’t make it pay if they use only their own money,” says sports economist and University of Chicago professor Allen Sanderson, who is critical of taxpayer funding of sports stadiums because, he contends, they often don’t deliver the economic benefits promised.

Pritzker, too, has repeatedly said he doesn’t support state financing of public businesses. In the case of the Sox park, “I start out really reluctant,” he told reporters. “And unless a case is made that the long-term investment yields a long-term return for the taxpayers that we can justify in some way — I haven’t seen that yet.”

Yet he has not completely slammed the door on some public backing. That could mean kicking in for sewers, roads, and other infrastructure. But just how far are state lawmakers willing to go? “We should not look to the original White Sox deal as a blueprint for what to do now, but as a guidepost for what we should be doing better,” says state representative Kam Buckner, whose 26th District includes Soldier Field and Bronzeville.

Tapping the ISFA again isn’t a certainty. After bankrolling the Sox and Bears, that agency has around $100 million in financing capability — far from what Reinsdorf says he needs. Lawmakers would have to approve boosting the ISFA’s bonding capabilities and the special tax district, which could face resistance from suburban and downstate pols, who couldn’t care less about a new Sox park.

For community activists, there’s another looming concern: the fate of Guaranteed Rate Field and the surrounding neighborhood. Alderperson Nicole Lee, whose 11th Ward would feel the brunt of a Sox departure, has cobbled together a “working group” of residents and business owners to make a case to the team to stay put in its current park. “It’s in great condition,” Lee says. “It’s not a new tax burden, it’s not a TIF handout.”

Some South Side groups fret that a new stadium deal will be pushed through Springfield without meaningful economic development plans for the area left behind. They want financing and other incentives for opening or expanding businesses, restaurants, and other ventures. “There has to be a broader conversation with the community,” says Bruce Montgomery, cofounder of the Urban Innovation Center, a locally focused economic development think tank on the Illinois Institute of Technology campus, just east of Guaranteed Rate.

Then there’s the matter of how the Chicago Bears, who are actively hunting for a new home, factor into lawmakers’ discussions of public subsidies. “All roads lead to Springfield,” says Buckner. “And the Bears and White Sox are two wheels that spin on the same axle.” Buckner is open to supporting a Sox move but also favors a “public-private” partnership to build a new Bears stadium on the lakefront, south of Soldier Field.

Yes, Big Jim Thompson is gone. But the wheeling and dealing over professional sports stadiums lives on.