Photos: Daniel Shea

Rincón de la Vieja National Park is a vast wonderland filled with ancient trees, postcard-perfect waterfalls, and bubbling geothermal mud pits that can reach a skin-scorching 200 degrees. Visitors flock here for the opportunity to hike near an active volcano, which is often obscured by cloud cover, lending the park a mysterious aura. Legend has it the volcano’s peak is haunted by an old witch who, in a Romeo and Juliet–style legend, became a recluse after her disapproving father threw her lover into the crater.

Listed as a “not to miss” site in The Rough Guide to Costa Rica, Rincón is exactly the kind of lush, tropical destination that has helped establish the Central American country as the ecotourism capital of the world. But despite the park’s wide appeal, locals will tell you that it is unquestionably wild. Pumas, jaguars, and at least four varieties of poisonous snakes lurk deep in the jungle. Some of the labyrinthine trails aren’t particularly well marked, and drug traffickers have been known to use them to smuggle narcotics into Nicaragua, just 25 miles to the north. And a section of the park was quietly closed for several days in 2009 and again in 2012 after hikers were robbed at machete point.

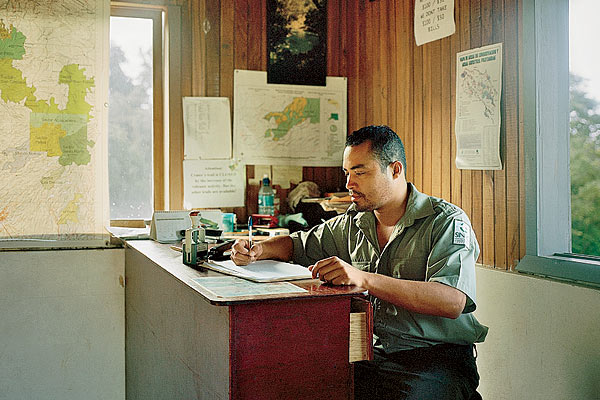

Some 300 visitors from all over the globe were there on August 11, 2009, the day a 28-year-old graduate student from Chicago arrived. He walked into the visitors’ information hut

just before 10 a.m. and scribbled his name—David Gimelfarb—into the guest book. He told the ranger in Spanish that he intended to take an easy three-kilometer loop called Las Pailas (the Cauldrons), after the steaming pots that pepper the path. Then the young man walked out of the hut, up and over a rickety footbridge spanning the cool waters of the Colorado River, and vanished.

Nearly four years later, I stumbled across a report about the disappearance while researching a travel story about the Rincón area. David’s tale resonated with me because I spent much of my twenties traveling the world solo, often hiking in wild places. And he had lived in Wrigleyville, just blocks from the apartment I shared with friends when I was his age. I couldn’t shake the chilling sense that what had happened to the young hiker could easily have happened to me.

Three weeks before I left for Costa Rica, I drove up to the Walker Bros. Original Pancake House in Wilmette to meet with his parents, Roma and Luda Gimelfarb, a pair of Russian émigrés who had settled in Highland Park and whose lives had been shattered by the disappearance of their only child. They had the hollow look and melancholy aura of souls who had survived a terrible ordeal but still hadn’t recovered.

I was struck by the fact that they hadn’t given up hope. “We believe David is alive,” said Roma, 66, his eyes searching mine to gauge a reaction.

They told me that there continued to be sightings of a man who resembled their slight, red-headed son. The latest report had come last October from Limón, on Costa Rica’s Caribbean coast, a five-hour drive from the national park. A man who was dirty, disoriented, and unable to speak had walked into a minimart there and gestured that he needed something to drink. Recognizing him from a newscast they’d seen on TV about David’s disappearance, a family took the stranger to a local police station. But after a brief interview, the police let him go without even snapping a photograph. The minimart’s owners insisted that the man was the missing American hiker.

Was this David Gimelfarb? Or just another false glimmer of hope for two grief-stricken parents desperate for good news?

The search for answers begins at the Hacienda Guachipelín, a rustic 54-room motel-style complex located on the lonely road that leads to Rincón de la Vieja. I arrived after dark this past February, making it through the motel’s security checkpoint just before the guard went home for the night. I was assigned room 17, next door to the one where David Gimelfarb had stayed.

He had been traveling alone, a last hurrah before starting his fourth year of graduate school. A doctoral student at the Adler School of Professional Psychology in Chicago, he volunteered as a therapist for the mentally ill at a community health center on the West Side, and he hoped to make that kind of work his career. Counseling was rewarding but stressful, and David’s parents worried that he was having a hard time coping with the recent loss of his beloved Russian grandmother, Valentina, who had cared for him from birth to kindergarten.

The trip had been hastily arranged only a few days before David was to leave. One of Luda’s coworkers at Kraft Foods, where she worked as a chemist, had recommended Costa Rica. It seemed perfect for David, who was fluent in Spanish, liked to hike, and needed to unwind. He was introverted, even a little socially awkward at times, and he told his adviser at Adler that the trip would be a way to build his confidence. “I told him I worried about him,” recalls Janna Henning, a coordinator of the school’s traumatic stress psychology program. “But he said that he’d traveled alone before and would be fine.”

Photograph: Courtesy of the Gimelfarb family

David had been shy and reserved since he was a child. When the Russian-speaking boy had started kindergarten at Braeside in Highland Park, his English had been poor. That early experience of feeling like an outsider had stayed with his son, says Roma, a chemical engineer at Morton Salt.

But friends say that David came out of his shell at Beloit College in Wisconsin, where he joined a fraternity, Phi Kappa Psi. His wry sense of humor and enthusiasm for techno helped him make friends, and though he never had a serious girlfriend, he wasn’t too shy to ask women out. “He had this theory he called ‘positivity,’ ” explains Ben Clore, a fraternity brother. “He’d give us these sermons about living positively and said you could have a better outlook on life.”

Unlike most young men his age, David wasn’t timid about baring his soul to his friends or voicing his questions about death, love, and the meaning of life. In a private Facebook message he posted just 13 days before he departed for Costa Rica, he wrote that he feared his own mortality and was grappling with how to confront his future. “Life is finite,” he wrote. “We must love it no matter what, so we can be satisfied with it when we look back on it.”

Perhaps this quest to live a memorable life was what had inspired a recent case of wanderlust. In the past year, David had traveled to Hawaii by himself to hike, and in his apartment he kept a copy of the book Vagabonding: An Uncommon Guide to the Art of Long-Term World Travel, which encourages the intrepid to take root and dig deep into local cultures.

But David must have known the risks of adventuring alone. Just before his senior year at Beloit, one of his fraternity brothers, David Byrd-Felker, who was from Madison, disappeared in southern Ecuador, likely while hiking by himself in a national park. No one can recall specifically how the disappearance affected Gimelfarb emotionally, but his college roommate, Ian Thomson, who is now an attorney in Milwaukee, says he can’t help wondering if David considered his fraternity brother’s fate when he decided to visit the park that morning in Costa Rica.

The day I set out to retrace David Gimelfarb’s footsteps was warm and dry, and Rincón de la Vieja’s canopy of majestic, twisting trees provided relief from the morning sun. But following the same trail that he had supposedly hiked, I had an uneasy feeling. It had started the night I checked into the motel, and it persisted the next morning as I explored the park. I finished the hike in less than two hours and walked back toward the information hut to talk to the park’s rangers.

The first ranger I spoke to was friendly enough—until I pulled out the missing-person flier with David’s picture. Seeing his face, the ranger threw his hands up over his shoulders and bolted. “I don’t know anything,” he said, quickening his pace as I tried to follow.

Inside the hut, a second ranger, who was responsible for registering visitors, didn’t have the luxury of physically ducking my questions. When I mentioned that some private guides had told me there had been robberies in the park, he said there had been “more than a few” but declined to elaborate. Later, Alejandro Masís Cuevillas, the director of the provincial parks authority, confirmed that sections of the park had been closed in 2009 and again in 2012; he said the robberies had all been “nonviolent.”

David Gimelfarb appeared contemplative, perhaps a little sad, the morning he vanished, according to a motel employee. He ate breakfast alone in the outdoor dining room around 9 a.m., then left to make the five-kilometer drive to Rincón de la Vieja in his rental car.

Something of a mama’s boy, he had called his parents the day before, just like he did every day in Chicago. David told them how he had met a girl at a nearby beach and hoped to rendezvous with her later. When his mother pressed for details—was she a local?—he would only offer that she “seemed very nice.” He told Luda he planned to hike the national park the following morning and complained that Hacienda Guachipelín was too quiet and far from the beaches and the action. He intimated that he might not stay there for the entire six-day trip.

The evening of the hike, Luda grew anxious when she did not hear from her son. At 10 p.m., she called his motel. He did not answer.

The next morning, his mother tried the motel again. When the front desk clerk said that David still wasn’t answering the phone, his mother insisted that someone go inside his room and check on him. “I told them, ‘If you don’t go in, I’m going to call the police, and if anything happens to my son, you are responsible,’ ” she says, still aggrieved by the memory.

Hours passed. That night, José Tomás Batalla, the owner of the motel, called the Gimelfarbs. David, he said, hadn’t slept in his bed the previous night. His suitcase was still in the room, and his rental car had been found in the lot of the national park.

“My heart sank when he said that,” recalls Roma, who went online and booked himself and his wife flights to Costa Rica.

By the time Luda and Roma arrived at the Liberia airport on Thursday, August 13, several Red Cross volunteers were already searching Rincón on foot. So they headed straight to the Hacienda Guachipelín, where the manager, Mateo Fournier Palma, unlocked room 16 and let them in. (They would later learn that Palma had already searched the room with two other witnesses who were never identified.)

The bed had been made, and David’s suitcase was still there. Two books of poetry—by Pablo Neruda and Federico García Lorca—were on a nightstand next to the bed. Palma opened the room safe. Inside, the concerned parents found their son’s passport, $600 of the $800 his father had given him in cash for the trip, and his cell phone, which contained a few photos of a beach he had visited the day before. “That didn’t make sense to us,” Roma says. “Why bring so many things with you on a hike but not the cell phone? There was no reception in the area, but he always used it to tell time.”

Judging from the items that were missing, they determined that David had likely carried with him his North Face backpack and his wallet, in which would have been his driver’s license, a few credit cards, and about $100. Missing, too, were his journal and an inexpensive point-and-shoot camera.

Fearing that David had gotten lost or injured in the park, they headed to Rincón to meet with rangers and Red Cross volunteers, whose numbers would swell into the hundreds that weekend. Luda’s boss at Kraft organized a committee to hire a professional search-and-rescue team, while David’s friends in Chicago started a Facebook group, Help Find David Gimelfarb, which attracted more than 1,000 members in the first days.

After Luda approached the U.S. Embassy in San José and received a noncommittal response—“They said, more or less, that he came here on his own,” she recalls, “so basically we are on our own”—David’s friends in Chicago mobilized and wrote letters to Mark Kirk, who was then an Illinois congressman, and other officials, urging them to pressure the embassy to help find the missing American hiker. (In a written statement, John Whiteley, a State Department spokesman based in Washington, D.C., said that the effort was “thorough and professional” and emphasized that the U.S. government does not have dedicated search-and-rescue personnel stationed at embassies overseas.)

Over the next few days, hundreds of friends and classmates staged demonstrations on the young man’s behalf at Daley Plaza and in front of Chicago news stations. On August 19, the U.S. military dispatched two helicopters with infrared sensors and more than a dozen uniformed soldiers from Soto Cano Air Base in Honduras to scour the park alongside a private helicopter pilot hired by the Gimelfarbs.

The effort lasted three days. Since Rincón de la Vieja opened in 1972, other hikers had gotten lost there, but all had eventually been found. A visitor had even fallen off one of the volcano’s craters and spent two nights clinging to a ledge before being rescued by a helicopter.

The team considered that David had perhaps changed his mind and, instead of taking the three-kilometer trail, attempted the more arduous journey up to the crater. That risky hike, now off-limits because of recent seismic activity, takes eight hours roundtrip. In this region, the sun sets at around 6 p.m. in August, so it would have been inadvisable for the young American to start out on the trail as late as 10 a.m.

The helicopters searched the crater extensively, and Roma himself made the grueling ascent with a park ranger. The wind was so fierce at the summit that they had to tie a rope around each other’s waists to stay on their feet. Meanwhile, Luda visited every hospital and jail in the area but found no clues. She even consulted a series of psychics, one of whom shared a dark vision: “He’s in the volcano. Go and live your life.”

The Gimelfarbs spent countless sleepless nights pondering what other misfortunes could have possibly befallen their son. Had he been attacked by a jaguar or bitten by a snake? Investigators all but ruled out those theories after no trace of his remains was found.

His parents’ best hope was that David had experienced some sort of mental breakdown and was perhaps wandering in a fugue state, which can occur when a person cannot process a stressful situation and forgets his identity. This temporary amnesia could have been triggered by a physical injury, such as a fall or a concussion.

A local resident brought Luda a megaphone, and the 63-year-old woman spent several days hiking the serpentine trails calling her son’s name. “We thought that if he had gone through some sort of traumatic experience, like a breakdown, that hearing my voice would be soothing to him,” she recalls.

Larry Maucieri, a neuropsychologist who was one of David’s professors at Adler, says that the fugue state scenario is highly unlikely—that such events are so rare they usually become the subject of academic studies. “One-in-a-million-type cases,” he explains.

The Gimelfarbs established a $10,000 reward (later upped to $100,000) and distributed thousands of fliers bearing a photo of David, along with a computer simulation of what he’d look like with long hair and a beard. With the money serving as an incentive, leads began to trickle in. One farmer said that he saw a disheveled hiker who, when confronted, had darted into the forest.

The family contacted Sarah Platts, a professional dog handler from Virginia, who in late September volunteered to fly to Costa Rica with her eight-year-old German shorthaired pointer, Jack, to join the search effort. Jack showed no interest in the trail to the volcano but seemed to pick up David’s scent near where the farmer had reported seeing the man flee. (The trail went cold when Jack fell into one of the volcanic mud pots and burned a paw.) Another dog team they hired to sniff for dead bodies found no evidence of a corpse in the park.

The Gimelfarbs couldn’t ignore a darker possibility: that their son had been the victim of a robbery—or worse. While the vast majority of the two million tourists who visit Costa Rica annually return home safely, crime is a serious concern. (The country of 4.7 million reported 525 homicides in 2009, giving it a per capita murder rate lower than Chicago, which reported 459 that year.)

In the four years since David vanished, at least eight foreigners have gone missing in Costa Rica, and 19 U.S. citizens have been murdered there since 2011. (In May 2011, the British Home Office issued a travel warning flagging the rising crime rate in the country.) Only two of the missing-person cases have been resolved: In 2011, about a year after a pair of Austrian expats disappeared in the remote Osa Peninsula, their bodies were found on a beach there. Investigators determined that they had been robbed and bludgeoned to death.

What if David had seen something in the park that he wasn’t supposed to? Drug smugglers, maybe. Or poachers. Perhaps he had left the park, headed back toward the motel, and somewhere along the way fallen victim to a con. One tip came in that the American hiker—who friends say did not use alcohol or drugs—had been spotted the evening after the hike at a bar in Liberia, about 30 minutes from the motel. “It turned out to be a whorehouse,” says his mother, who went herself to investigate. “But I showed all the girls his photo and nobody remembered him.”

What if he had been robbed on the way back to the motel? Or abducted and his organs harvested? It sounds far-fetched, but the black market for donor organs is a growing problem in Costa Rica and Nicaragua (and was the subject of an investigation by the Mexican newspaper El Universal earlier this year).

The list of frightening scenarios was endless. To investigate every credible one, the Gimelfarbs hired four private detectives, both in Costa Rica and back in the States. Vugar Askerli, a former military intelligence officer from Azerbaijan, spent a month in Central America looking for David and came away believing that the young man left the park and was killed near the motel.

Initially, three motel employees had claimed that they saw the American back at the Hacienda Guachipelín around 2 p.m. the day he vanished. (Two employees later changed their stories.) Given that information, Askerli supposes that the perpetrator drove the car back to the park to make it look like David went missing while hiking. “It would be easy to cover up a crime like this in that area,” contends the investigator. “The rivers are filled with crocodiles. No one would ever find the body.”

Another private investigator suspects that David got lost after sunset, wandered onto private property on the edge of the park, and was mistaken for a poacher or a thief. He could have been shot dead and his body disposed of, either in the jungle or in a river.

The Organismo de Investigación Judicial—Costa Rica’s equivalent of the FBI—conducted its own investigation. Agents interviewed motel employees and park rangers but, according to the final report, failed to talk to other Hacienda Guachipelín guests or hikers in the Rincón area.

What’s more, they did not conduct a forensic search of David’s room or rental car. (The lead investigator on the case, Luis Guillermo Fonseca, agreed to answer questions but never did so, despite repeated requests.)

On November 6, 2009, the OIJ closed its investigation without a conclusion. Translated into English, the report ends by saying: “All our efforts have come up empty.”

“We just want a complete and thorough investigation,” says Roma, who estimates that he and his wife have spent $300,000 on their search. “We’ve never had that.”

Ticos, as Costa Ricans are called, can be fiercely patriotic. And they don’t like to consider the possibility that something bad happened to a tourist in their country. Sitting at a table in his motel’s open-air restaurant with the panoramic view of the verdant, mountainous landscape behind him, José Tomás Batalla, the fit, deeply tanned Costa Rican who owns Hacienda Guachipelín, waves the crime theory away. “You can get mugged anywhere,” he says when I ask about the machete attacks in the park. “Rome, Amsterdam, Paris—even Chicago. The Gimelfarbs are channeling their grief against Costa Rica, trying to link every robbery that occurs to their son.”

Batalla believes that David is alive and living the life of a hermit somewhere, perhaps even on a Nicaraguan beach not far from the park. (Neither Nicaragua nor Costa Rica strictly enforce their immigration laws, so foreigners can easily live in the area without a visa.)

“A lot of people assumed that he was running away from something in the States, trying to hide or escape,” said Laurens Alvarado Hidalgo, a guide I met at Rincón. Nicaragua is a cheaper alternative to Costa Rica, so if David had wanted to disappear, it would be a logical option.

Intrigued by a lead from a local man who told OIJ investigators that he had smuggled someone who matched David’s description across the border, I showed the missing-person flier to dozens of people at hostels and expat hangouts in San Juan del Sur and Granada. I encountered nothing but curiosity or indifference.

Rob Thomas, a 50-something Vermont native who moved to San Juan del Sur in 2006 to open a café, smiled when I asked him if David looked familiar. “I can’t say I remember the face,” he said, studying the flier. “But a lot of people come down here to get lost.”

David’s closest friend from Adler, Christine Shaw, scoffs at the notion that her classmate traveled to Costa Rica to fall off the grid. The night before he left, she says, he called to confirm dinner plans they’d made for the Sunday night after his return.

For a long time, she was certain that her friend was still alive. Now, she says, her voice cracking, it is “just too hard for me to keep believing.”

Ben Clore, the fraternity brother, says that, early on, he thought it possible that David had decided to live in the forest for a while. But he now fears the worst. “He was a free spirit,” says Clore. “I could see him disappearing for a year, maybe. But four? No. As time goes on, that theory becomes less realistic.”

Then there’s Sean Curran, a detective with the Highland Park Police Department, who was brought on to the case when the Gimelfarbs reported their son missing to U.S. authorities. (The FBI typically takes on overseas missing-person cases only if the host country requests agency assistance.) After combing through David’s belongings, reading his journals, talking to his friends and teachers, and examining his financial situation, Curran says there is little evidence that would point to a conscious decision to disappear.

Only two clues give him pause: the copy of Vagabonding, which is the book about long-term travel that he found in David’s apartment, and a series of maps he discovered during a search of the graduate student’s laptop. On the night before David was to leave for Costa Rica, he had examined maps of Nicaragua, Honduras, Colombia, Peru, and Chile—a curious detail, since his trip was to last only six days.

But David’s bank account was not touched after he left the United States, and he never applied for any additional credit cards. And his adviser at Adler provided a psychological profile attesting to the fact that the young man seemed mentally strong and highly unlikely to abandon his family and clients.

Sitting in a conference room at the police department on a gloomy day in late April, Curran, a father himself, said the case remains troubling. “I don’t think he intentionally did this to his parents.”

I spent the better part of six months trying to untangle the mystery of

what happened to David Gimelfarb. I interviewed dozens of friends and people familiar with the case, sifted through reports from investigators, and spent hours with his parents. In the end, I don’t believe that this young man chose to disappear.

But he may have been more emotionally fragile than anyone realized. In the confessional he penned on Facebook two weeks before his trip, David said that he sometimes loved the “adventure of being single” but also suffered through “excruciating loneliness.” And that the experience of losing his grandmother brought the idea of his own mortality closer. “I will die someday,” he wrote. “There is no way to know what the future holds, and it really never comes exactly as we envision it.”

The odds are that David Gimelfarb is dead. But we may never know for sure. Mike Byrd and Maggie Felker, the parents of David Byrd-Felker, the other missing Phi Kappa Psi, ultimately came to peace with the idea that they’ll likely never find out what happened to their son. “Western society is enamored with the concept of closure,” says Byrd, who founded David’s Educational Opportunity Fund to help young Ecuadorians go to school. “But there is ambiguous loss all around us. I’m probably better off not knowing what happened.”

For the Gimelfarbs, the search goes on. Roma says he was too consumed by the search to be useful to his company, so he retired. Luda also left her job; she says she has tried therapy but found it too painful.

Each August, Roma and Luda return to Costa Rica on the anniversary of their son’s disappearance to chase leads and to press for a renewed investigation. Every time there is another sighting, they pursue it.

Earlier this year, a family friend, Nicolas Bridon, volunteered to travel to Costa Rica to investigate the tip from the minimart in Limón. Bridon met with the family who had taken the dirty, disoriented mute to the police, and he interviewed the officer who had been at the station. The family seemed sincere, and the police officer insisted that the young Caucasian he encountered was indeed the same man as on the flier.

While these people could be mistaken, it’s clear that David Gimelfarb, with his pale skin, red hair, and freckles, would stand out in a crowd in Costa Rica.

“We look at every face that could be David and wonder, Could that be our son?” says Luda, measuring her words, trying not to break down.

Every day, rain, snow, or sleet, she leaves her home on a quiet street near Ravinia and walks to Rosewood Park, where she always sits on the same wooden bench facing Lake Michigan. There she talks to her son.

“I tell him what’s going on,” she says. “I tell him I love him. And I ask him questions. But he never answers.”

Comments are closed.