|

Photo: Matthew Gilson

|

|

Union Station’s Great Hall, the last vestige of Chicago’s glory days as the nation’s railroad hub.

|

Halfway through Alfred Hitchcock’s stylish 1959 thriller North by Northwest, Cary Grant arrives in Chicago. On the run from the law and a gang of evil spies, he descends from the 20th Century Limited disguised as a porter. Accompanied by Eva Marie Saint, he proceeds into LaSalle Street Station, at which point Ms. Saint suggests that Grant ought to change back into his gray suit.

“Where do you propose I do that?” he asks archly. “In Marshall Field’s window?”

Grant’s cinematic sojourn in the Windy City is full of bittersweet moments like that one: it’s wonderful to catch these images of Chicago some 50 years ago, but sad to realize how much we’ve lost-or are about to lose. The 20th Century Limited, the elegant passenger train that once ran between New York and Chicago, ceased operations in 1967, and the vintage LaSalle Street Station, completed in 1925, fell to the wrecking ball in 1981. This month, many Chicagoans will celebrate that cherished Christmas ritual: enjoying the windows at Field’s. The windows will likely be there next year, but the familiar name will be gone. Yet rather than lament what’s lost, take a minute to survey the landscape.

If you know where to look, postwar Chicago-an era when Carl Sandburg’s hardworking City of the Big Shoulders took on Frank Sinatra’s rakish razzmatazz-survives to this day. You can find it in the Great Hall at Union Station (above) or the glass-walled hangars at Midway Airport. It exists in an accordion shop in Oak Lawn and in the memories of a hard-hurling pitcher from the ’59 White Sox. The following pages reveal these hallowed spots and many more-including one lingering look at Field’s at Christmas.

|

Photo: Matthew Gilson |

|

Danny Newman, press agent extraordinaire and an early promoter of Lyric Opera of Chicago |

Der Ring des Telefonen

A “thrice-wounded battle-scarred veteran” (as he puts it), Danny Newman returned home from World War II eager to pick up the strands of his life. Born in Chicago’s Douglas Park in 1919, Newman had worked as a theatrical press agent since he was 14. Now he resumed that career, while also running the Astor Theatre, a Loop movie house. There, in 1953, two young Chicagoans, Carol Fox and Lawrence Kelly, visited him regularly. With the conductor Nicola Rescigno, the pair planned to start a new opera company in town, and they wanted Newman to sign on to what would ultimately become Lyric Opera of Chicago. “They told me their dreams and ideas and hopes,” says Newman. “I was over my head with activity, but I wanted to achieve something for Chicago.” Priming his contacts around the globe, Newman ignited enthusiasm for the project, and the company’s inaugural performance, in November 1954-Vincenzo Bellini’s Norma, featuring Maria Callas, then little known in her native United States-scored an immediate triumph. “It was an electrifying success,” says Newman. “In one moment, Callas’s American career and Lyric’s [reputation] went into orbit together.” Newman remained active with the company until his retirement in 2003, though he still keeps an office at Lyric. There he works on his forthcoming memoir, Inside Insights of a Theatrical Guru-the successor to Subscribe Now!, his acclaimed 1977 book that let other not-for-profit arts groups in on the secrets of creating and maintaining large audiences.

Train of Thought

Sit on the long wooden benches inside Union Station’s Great Hall, and it’s possible to conjure up a time when some 300 trains and 100,000 passengers moved daily through this transportation hub. An original component of Daniel Burnham’s 1909 Plan of Chicago (and completed, in 1925, by Graham, Anderson, Probst & White, a successor to Burnham’s firm), the neoclassical station suffered a major setback in the late 1960s when developers demolished its eastern façade along the South Branch of the Chicago River. But the Great Hall retains all its Beaux-Arts glories, from its mass of travertine and Tennessee marble to its immense Corinthian columns (some topped by enigmatic statuary, such as the hooded representation of an owl-bearing Night) to the majesty of its 112-foot-high vaulted roof. Amtrak and Metra riders still use the station, and lately the hall has become a popular venue for gala fundraisers. But the best time to visit remains the off-hours, when you can sit and imagine that the next train pulling in just might be the Broadway Limited, full of movie stars and sports heroes eager to alight in the Windy City after their 18-hour trip from New York. (210 S. Canal St.)

|

Photo: Leonard Gertz |

|

Nummy nova: Maurice Lenell’s jelly star cookie |

Mama’s Little Baby Loves . . .

From the timeless packaging (the image of a freckle-faced boy sticking his head out of a cookie jar) to the recipe, there is nothing fancy about Maurice Lenell cookies-just lots of shortening and sugar to make them extra rich, sweet, and crumbly. A staple of Chicago childhoods since the company opened for business in 1937, the cookies are still made locally in five varieties: jelly stars, almonettes, coconut bars, chocolate chip, and pinwheels. Pick up a pack at local grocery stores, online (http://www.ecomallbiz.com/lenell), or in the store adjacent to the company factory (4474 N. Harlem Ave., Norridge; 800-323-1760). Collectors even go gaga over Lenell’s holiday cookie tins-as if someone needed another incentive to eat his way through an entire two-pound container.

Young at Heart

|

Photos:Matthew Gilson |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

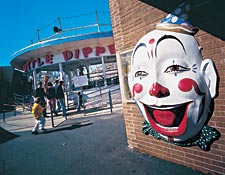

Founded during the Depression by Arthur Fritz, KiddieLand still evokes delighted squeals with its array of amusements from simpler times. |

|

Compared with the heart-stopping thrill rides at today’s mega–amusement parks, the Little Dipper-the 55-year-old wooden roller coaster at KiddieLand-seems as intimidating as a speed bump. So why is it so much fun? Must be the company you keep-hordes of bright-eyed kids, most of them under the age of ten, who climb aboard the ride with an infectious anticipation that’s impossible to resist. Young children and their parents will also delight in the German carousel, the Ferris wheel, the Log Jammer (a water-dousing flume ride), the small train that circles the 17-acre park, and a score of other rides. Now, which way are the bumper cars? (8400 W. North Ave., Melrose Park; 708-343-8000)

|

Photo: Matthew Gilson |

| Soul bellows: Italo-American’s Anne Romagnoli |

Squeeze Play

The New Yorker ran a cartoon several years ago of an old man, drink and smoke in hand, sitting alone in a bar with his accordion nestled neatly beside him. The punch line? It was back in ’52 that the hits stopped coming. So it seems, until you step into the Italo-American Accordion Company, the 85-year-old establishment run today by Anne Romagnoli and her two grandchildren. A squeezeboxer’s paradise, the store offers repair and restoration service and stocks a colorful array of new and used instruments-everything from the high-end Crown to the venerable Polkamasters and the tried-and-true Cavalier. (5510 W. 95th St., Oak Lawn; 708-422-2992)

|

Photo: Matthew Gilson |

| Most South Park Manor bungalows were built between 1915 and 1930. |

House Party

With their tidy rows of bungalows, the tranquil streets of South Park Manor resemble scores of other Chicago neighborhoods-though with a twist. Because of generous rights of way put in place in 1869, the area’s houses-many of them with their original clay tile roofs and decorative stained glass-sit 50 feet back from the street, making for a wider and lovelier prospect along the sidewalks. What’s more, those houses, built primarily between 1915 and 1930, were the product of an uncharacteristically large number of builders and architects, and their varied designs make for a lively streetscape-a welcome reprieve from the monotony that can prevail elsewhere in the city’s Bungalow Belt. Once home to a polyglot mix of European Americans, South Park Manor (bounded by Michigan and Calumet avenues) now has a mostly African American population, and they shop in the thriving retail strips along 75th and 79th streets, the area’s northern and southern boundaries.

|

Photo: Matthew Gilson |

Jaws

On the Calumet River, in the shadow of the 95th Street Bridge-the same bridge jumped by the Bluesmobile in 1980’s Blues Brothers–Calumet Fisheries serves up scrumptious, no-frills takeout fish. Some like it fried (shrimp, smelt, oysters, and catfish), but the smoked offerings-which can also include chub, salmon, and trout from the smokehouse out back-are the preferred fare. (3259 E. 95th St.; 773-933-9855)

Party Palace

|

Left: Raymond Trowbridge/Chicago Historical Society, Right: Matthew Gilson

|

|

|

|

|

The Aragon in 1926 (left), the year it opened; cars whiz by the ballroom in 2005 (right). |

|

When the Aragon Ballroom opened its doors on July 15, 1926, the first person in line was Chicago mayor “Big Bill” Thompson. Another 8,000 people streamed in behind him, eager to see the nation’s newest dance palace. They weren’t disappointed. Inside, at a cost of nearly $2 million, William and Andrew Karzas had created an idealized vision of Spain-or was it Morocco, or the Orient?-that included silver minarets, plaster dragons, a cobalt blue sky accented with twinkling stars and drifting clouds, and an octagonal dance floor that floated on a cushion of felt, cork, and springs (“Beauty so exquisite that it transcends the loftiest imagery of the most poetic mind,” gushed one ad). In 1927, WGN began near-nightly radio broadcasts from the Aragon, giving listeners around the country a chance to envision elegantly clad dancers-jackets and ties were obligatory for men, semiformal gowns for women-swaying to the sounds of Benny Goodman, Glenn Miller, and Tommy Dorsey and their orchestras. The party went on through the thirties, through World War II and the fifties. But attendance began to dip as enthusiasm for the big bands waned, and in 1964, William Karzas sold the Aragon to a couple of promoters who replaced ballroom dancing with ice skating and boxing and wrestling matches. A subsequent series of owners (including Hair’s Michael Butler) introduced rock ‘n’ roll to the Aragon (which, in the guise of a psychedelic discothèque, was known briefly as the Cheetah Club), and today rock remains the music of choice at this four-story temple of faux Iberian glory. (1106 W. Lawrence Ave.; 773-561-9500)

Swing Shift

|

Photos:Joseph Desler Costa |

|

Showin’ how it’s done: Pete and Linda Frazier, the self-styled “King and First Lady” of steppin’ |

Its roots predate World War II, springing from such dances as the jitterbug and the lindy hop. In the 1950s it became the bop, and after a few refinements, perfected in Chicago’s South and West Side clubs, it became known as “steppin’.” An improvisational dance form based on an eight-count beat-and cool, colorful threads-Chicago steppin’ achieved a more recent breakthrough following the release of the 1997 movie love jones (set here) and R. Kelly’s 2003 single and music video “Step in the Name of Love.” Interested in steppin’ out? Beginners can take a lesson on Tuesdays and Saturdays at the South Shore Cultural Center (7059 S. South Shore Dr.; 312-259-1443) or Tuesdays, Wednesdays, Thursdays, and Saturdays at Sweet Geogia Brown (4167 W. 183rd St., Country Club Hills; 708-798-6333) before heading out to one of the local clubs.

| Steppin’ Out |

| 3G’s 14202 S. Cottage Grove Ave. Dolton 708-841-7870 Tuesdays and Wednesdays, 7 p.m. |

| The New Dating Game 8926 S. Stony Island Ave. 773-374-8883 Thursdays and Saturdays, 7 p.m. |

| B ‘n’ J’s Lounge inside the Matteson Holiday Inn, at the intersection of Lincoln Highway and Route 57 708-747-3500 Fridays, 7 p.m. |

| 50 Yard Line 69 E. 75th St. 773-846-0005 Tuesdays at 6 p.m. and Saturdays at 4 p.m. |

Blues Power

|

Photo: Andreas Larsson |

|

From left: Honeyboy Edwards, Billy Boy Arnold, Koko Taylor, Sam Lay, Jimmy Dawkins, and Bob Stroger |

This fall, Chicago reunited six top performers from Chicago’s golden era of blues for a photograph at the venerable West Side music joint Rosa’s Lounge (3420 W. Armitage Ave.; 773-342-0452). Older and wiser, the musicians exchanged pats on the back, weighed future collaborations, and reminisced about gigs with Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, Lightnin’ Hopkins, Big Bill Broonzy, and Sunnyland Slim. These six continue to call Chicago home, despite tugs from the lucrative European blues circuit. “Chicago is the only city in the world where there is blues every night of the week,” says Billy Boy Arnold, the man who gave Bo Diddley his name. “Isn’t that reason enough to stay?”

One of the few living bluesmen with an authentic Mississippi Delta sound, the acoustic guitar player Honeyboy Edwards (born 1915) was touring the country with Big Joe Williams by age 17. “He taught me everything I know,” says Edwards, who migrated to Chicago in 1945. Twelve albums later, Edwards continues to perform, including at Millennium Park on February 5, 2006, in honor of Black History Month.

When he was 12, young Billy Boy Arnold-the rare bluesman born (1935) and raised in Chicago-knocked on the door of Sonny Boy Williamson’s home and asked the legendary harmonica player for a lesson. Arnold ultimately found success backing Bo Diddley before going solo. The Electro-Fi label released his tenth album in October. Catch him live at Rosa’s on December 10th.

A gospel singer, Koko Taylor (born 1935) got her big blues break in 1962 when the Chess Records talent scout Willie Dixon spotted her singing with Howlin’ Wolf’s band. Despite a long hospitalization in 2003, the “Queen of the Blues” has returned to the performance circuit and is working on a new CD. Catch her on November 19th with Sam Lay and the Siegel-Schwall Band at Governors State University (1 University Parkway, University Park; 708-235-2222).

The drummer Sam Lay (born 1935) played with such blues legends as Howlin’ Wolf, Muddy Waters, Jimmy Reed, and Otis Spann-and, as a member of the Paul Butterfield Blues Band (one of the first racially integrated blues groups in Chicago), he backed Bob Dylan in 1965 when the folkie went electric at the Newport Folk Festival. On November 19th, he joins Koko Taylor and the Siegel-Schwall Band.

“He’d come down in his slippers sometimes and play,” recalls

Jimmy Dawkins (born 1936) of his early gigs with Lester Hinton, circa 1955. Dawkins, known for his lightning-fast guitar playing, went on to perform with such greats as Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, and Sunny Thompson. A guitarist and producer, Dawkins appears on My Head Is Bald, the new Delmark release from Chicago bluesman Tail Dragger.

Every good blues band needs a bassist, a fact that has kept Bob Stroger (born 1932) employed since his first gig at Turner’s, a club at 39th and Indiana, in the early 1950s. The congenial freelancer has played with the likes of Sunnyland Slim, Eddy Clearwater, and Otis Rush, whom he credits for getting him into the blues. Stroger plays at Rosa’s with Billy Boy Arnold on December 10th.

Frieze Frame

|

Courtesy: Dr. David Baldwin/Rush Photo Group/USPS |

In 1938, as Chicago and the nation began to recover from the Depression, the social realist painter and printmaker Harry Sternberg unveiled Chicago: Epoch of a Great City, a massive (180 square feet) oil-on-canvas mural at the Lake View branch of the U.S. Postal Service. Originally created for the Works Progress Administration and beautifully restored in 2003, the mural alludes to the Fort Dearborn massacre and the Great Fire, but concentrates more on a brawny and vital city of steelworkers, scientists, and skyscrapers-a Chicago, in other words, that would fully re-emerge in the decade following World War II. (1343 W. Irving Park Rd.)

|

Photo: Nathan Kirkman |

|

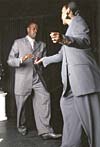

Distilled life: the backroom of the 117-year-old House of Glunz |

Grand Crew

It’s a touch dusty, slightly cluttered, and a little dark-in short, The House of Glunz seems more like a wine cellar than a shop. But as noted in tall gold lettering outside the store, this family-owned establishment has catered to customers since 1888. Day-to-day operations are now handled by its fourth-generation proprietor, Christopher Donovan, with plenty of input from Barbara Glunz, his mother, who once lived in an apartment upstairs. She is the best guide for a walk around the store’s backroom, whose antique displays show off a dazzling collection of green, rose, and gilded glassware. “We do have computers now,” says Glunz, nodding to progress, “but our style hasn’t changed. ‘Merchants’ isn’t a proper term anymore, but that’s really what we are. We have tasted virtually everything in the store.” (1206 N. Wells St.; 312-642-3000)

|

Photo: Matthew Gilson |

| Completed in 1958, Chicago’s first post-Depression skyscraper remains a stunning symphony in stainless steel and glass. |

True as Steel

On a visit to Chicago circa 1960, the architect Frank Gehry first set eyes on the Inland Steel Building, which today remains a bold statement in stainless steel and glass. “It was very awe inspiring,” Gehry recalls. “I made a special trip to see it. It still represents a breakthrough to the future.” Designed by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill and completed in 1958-making it the city’s first post-Depression skyscraper-the 19-story building (now known by its address, 30 West Monroe) has a revolutionary open floor plan, which the designers made possible by relegating the elevator and stairs to a separate structure to the east. The building’s latest owners-a consortium that includes Gehry-have pledged to preserve the structure’s timeless façade. “We are going to redo some of the things that are historically incorrect,” Gehry says, “like stuff in the lobby that has to be changed. I am going to design a new reception desk, but I will do it in the spirit of the place. I’m not going to try and inject myself there.”

|

Photo: Joseph Desler Costa |

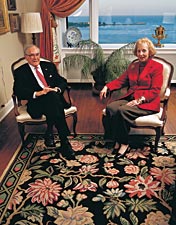

| A peerless pairing: Newton and Jo Minow |

Hometown Heroes

After 56 years of marriage, Jo and Newton Minow are still engaged in a formidable romance. The couple met as students at Northwestern University when Newton, a Milwaukee native, elected to stay in Chicago after his military tour of duty (in China, Burma, and India) during World War II. But in addition to having eyes for each other, they both harbor a deep affection for the city they call home. “We [lived] in Washington twice,” recalls Jo, a lifelong Chicagoan. “People said, ‘You won’t come back [to Chicago].’ I said, ‘Just you watch.'” Their affection for the city makes them models of civic involvement-though their efforts have also played out on a larger stage. One of those stints in D.C. began in 1961, after President John Kennedy tapped Newton to lead the Federal Communications Commission-which led to Minow’s characterization of television as “a vast wasteland.” (Newton, 79, a senior counsel at the Chicago law firm of Sidley Austin Brown & Wood, slyly refers to today’s TV offerings as “half vast.”) The couple work with the Chicago Historical Society, the Ravinia Festival, WTTW–Channel 11, and the Jane Addams Juvenile Court Association, among other organizations. Though they travel regularly to see their daughters-Nell, Martha, and Mary-they are always happy to come home to Chicago. “When we come in from the airport and I see the skyline, I just want to throw my arms around it,” says Jo. “I love this city.”

|

Photo: Matthew Gilson |

| Wall of glass: one of Midway Airport’s 52-year-old hangars |

In Plane Sight

For nearly 30 years, the world’s busiest airport was in Chicago-on the Southwest Side. From 1932 to 1961, passengers flocked into and flew out of Chicago Municipal Airport, which changed its name, in 1949, to Midway Airport (at 55th Street and Cicero Avenue). While a series of restorations have obliterated the 1947 terminal (which once had a stylish observation deck and a popular restaurant called the Cloud Room), two 52-year-old hangars, designed by Charles Whitney and Othmar Ammann (the structural engineer who helped build New York City’s Lincoln Tunnel and George Washington Bridge), recall the airport’s halcyon days. Vaulted roofs span the reinforced concrete structures, which are fronted by massive sliding glass doors. Originally built for Trans World Airlines and United, the hangars, situated along 55th Street and visible from the passenger concourse, are now used by ATA and Southwest Airlines.

|

Photo: Matthew Gilson |

|

The Skyway’s newest owners upped the toll to $2.50. |

Time’s Toll

Though recently renovated (at a cost of $250 million), the 7.8-mile-long toll bridge still shows its age-but in a good way. Spanning the Calumet River to connect the Dan Ryan Expressway with the Indiana Toll Road, the Chicago Skyway stands as a brawny steel-and-concrete reminder of the postwar interstate highway boom-and the bright-red neon lettering atop its toll plaza is right out of the Eisenhower era. When the skyway opened in April 1958, drivers paid a quarter to cross; the toll gradually rose, and after a 50-cent increase by its new owners-the Cintra-Macquarie Consortium, which last year paid $1.8 billion to lease the bridge for 99 years-the cost is now $2.50. But from a certain perspective, the price is a bargain, since the bridge transports people not only to another state, but to an entirely different time.

|

Photo: Matthew Gilson |

|

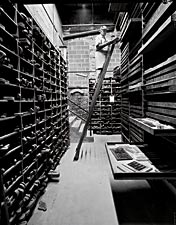

A ladder to the past: inspecting age-old molds at Decorators Supply |

A Cast of Thousands

Originally established in 1883 as a manufacturer of “artistic decorative accessories,” Decorators Supply Corporation came into its own as a provider of cast ornamental plaster in 1893 when it helped create the chimerical White City of the World’s Columbian Exposition. After the fair, the company tapped the artistic talent lingering in Chicago and created 14,000 different molds, some of which were used to embellish Marshall Field’s State Street store, the South Shore Country Club, and the Midwestern movie palaces of the 1920s. Today that historic catalog, augmented by a line of wooden ornamentation, remains intact, a priceless resource for people restoring old buildings or hoping to add a timeless touch to some new construction. (3610-12 S. Morgan St.; 773-847-6300 or www.decoratorssupply.com)

|

A Walk on the Wild Side

The winner of the first National Book Award for fiction, Nelson Algren’s 1949 novel The Man with the Golden Arm preserved forever West Division Street and the sad lives of its down-and-out denizens. The book’s protagonist, Frankie Machine-a card dealer and would-be drummer addicted to morphine-comes to a sad end. But the 1955 movie, directed by Otto Preminger and starring Frank Sinatra, has a rosier conclusion-and a studio lot stands in for the mean streets of Chicago.

Paper Chase

Started by three Pieritz brothers in 1895 as a cigar and newspaper shop, the Oak Park stationery store Pieritz Bros. has been at its current location for 35 years. Today it is run by the sculptor Deborah Pieritz, a granddaughter of one of the founders, and her brother-in-law, John Roberts. A step back in time to a pre–OfficeMax world, the 1,500-square-foot space is crammed floor to ceiling with vintage fountain pens, manila coin envelopes, rubber stamps, unusual German pencils and sharpeners, russell+hazel binders, and other run-of-the-mill office supplies-as well as stuff that’s not for sale, including antique typewriters, printer’s supplies, and a bottle of whale oil, once used as a lubricant for typewriters. (401 South Blvd.; 708-383-8710)

|

Photo: Joseph Desler Costa |

|

At home with Billy Pierce of the Go-Go Sox: “I always believed in going after the hitter.” |

Playing Hardball

While anchoring the Chicago White Sox pitching staff from 1949 to 1961, Billy Pierce never worried about how many pitches he had thrown or when a reliever might come in to spell him. Instead, the lefty just took the ball and pitched hard-and often. During his 20-year career (which included stints with the Detroit Tigers and the San Francisco Giants), Pierce pitched 193 complete games and compiled a lifetime record of 211 wins and 169 losses. “I always believed in going after the hitter, throwing as many strikes as I could and putting him on the defensive,” says the seven-time All-Star, who led the American League in strikeouts (186) in 1953 (when he also had seven shutouts and pitched 51 consecutive innings without allowing an earned run), in earned run average (1.97) in 1955, and in wins (20) in 1957. His postgame regimen was simple, too. “I would take a shower, and sometimes they would put a little alcohol on my arm to close the pores,” he says, laughing. “Then I would dress, come home, and eat.” Retired now at 78 and living in Lemont with his wife, Pierce does some occasional community relations work for the Sox and serves as chairman of Chicago Baseball Cancer Charities.

Grandfather Clause

|

Matthew Gilson

|

|

|

|

|

Colorful combo: the Original Rainbow Cone is a pastiche of ice creams topped with orange sherbert. |

|

The pink stucco building is a longtime South Side landmark, but it’s the tasty concoction served inside that is the real classic. Founded in 1926 by Joseph Sapp, the Original Rainbow Cone serves up a multihued concoction composed of chocolate, strawberry, pistachio, and Palmer House (an amalgam of cherries and walnuts) ice creams topped with orange sherbet. Owned now by Sapp’s granddaughter Lynn Sapp-Stenson, the place offers sandwiches as well as other frozen treats, but it’s Grandpa’s imaginative creation that still packs them in. (9233 S. Western Ave.; 773-238-7075)

Cocktail Culture

|

William Zbaren |

Brittney Blair |

|

Petey Kattos and his restaurant’s neon martini |

|

The neon martini glass perched out front says it all. Here’s a joint where the steaks are big, the drinks are strong, and, my God!-smoking is still allowed. For nearly 45 years, Petey’s Bungalow Lounge has been serving up meals that seemingly went out of style right about the time Eisenhower left the White House. Grab a table, order a cocktail or two, and chat with your waitress, who is guaranteed to call you “hon” before the night is out. A favorite entrée ($23) begins with relishes-a silver tray filled with raw veggies, small bowls of beets, cottage cheese, macaroni salad, and vinegar-soaked cucumbers-and a basket of piping hot garlic bread. After the soup and salad, the 16-ounce fillet arrives, baked potato on the side. Finish up with a cup of coffee and a scoop of peppermint ice cream-and on the way out, shout hello to the owner, Petey Kattos, who, at 69, still works the kitchen every night of the week. (4401 W. 95th St., Oak Lawn; 708-424-8210)

|

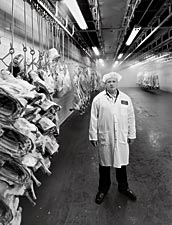

Photo: Matthew Gilson |

| The big chill: Dennis Chiappetti, president of Chiappetti Lamb and Veal |

In the Jungle

Situated on the northern boundary of the city’s old stockyards, Chiappetti Lamb and Veal is the last slaughterhouse and meatpacker in Chicago. Founded in 1945, and in the same family for four generations, this old-line Bridgeport establishment processes 1,500 lambs a day and 350 calves a week-some in accordance with Jewish and Muslim dietary laws. You can find Chiappetti’s veal and lamb products, a favorite of local chefs, at Treasure Island and Butera-or visit the company’s Web site to order online. (3810 S. Halsted St.; 773-847-1556 or www.chiappettilambandveal.com)

The Ties That Bind

|

Courtesy The Chicago Transit Authority

|

|

|

|

|

Mayors on the move: Mayor Martin Kennelly (left) and his successor, Mayor Richard J. Daley (right), celebrate key moments in the early days of the Chicago Transit Authority, a postwar creation. |

|

On February 24, 1951, Chicago mayor Martin Kennelly cut a ribbon (above left) to officially inaugurate the city’s new Dearborn Street Subway (now part of the Blue Line), a link between the Logan Square and Humboldt Park branches already managed by the Chicago Transit Authority. (Pictured with Kennelly are, from left, Wallace Hurford, a CTA motorman; Monte Blue, the movie cowboy who emceed the ceremony; and Virgil Gunlock, superintendent of subways.) Though today it seems as if the CTA has been around nearly as long as Lake Michigan, the agency is actually a postwar invention, created by the Illinois legislature in 1945 and beginning operations in October 1947. A wave of reorganization and expansion followed, including construction of the Congress Line, which ran along the median of the Congress (later Eisenhower) Expressway, a pioneering design for urban transportation. Above right: in 1955, Mayor Richard J. Daley smiles after hammering home a ceremonial first spike for the Congress Line (now also part of the Blue Line).

Yule Memories

| Courtesy Marshall Field’s | |

|

|

|

|

|

Top: Uncle Mistletoe spirits two children off to Santa Claus Land in a series of 1946 windows. Below: Christmas in the Walnut Room, 1953

|

|

For many Chicago children and their parents, no Christmas is complete without a downtown visit to Marshall Field’s to gaze at the holiday tale unfolding in the State Street store’s windows and enjoy a festive meal upstairs in the Walnut Room. The tradition of a lavishly decorated tree in the Walnut Room dates back to 1907-though fire safety has dictated an artificial conifer since the 1960s. In 1944 and 1945, the Field’s windows first related Clement Moore’s “A Visit from St. Nicholas.” In 1946, they introduced a new character, Uncle Mistletoe, who enjoyed a long run of popularity, which included a local TV show that ran seasonally from 1948 to 1952.